F L A U N T

Walking down Philadelphia’s Benjamin Franklin Parkway, the tree-lined sidewalks and sparkling fountains breathe calm into the city’s pulse. Amid the buzz of traffic and the murmur of museum-goers, Calder Gardens (which was unveiled this fall) waits like a rest in the city’s rhythm, delicate and kinetic all at once. Here, and inside the multiple galleries of the onside Calder Gardens Building, Alexander Calder’s steel arcs, spirals, and discs hover, defy, and pirouette, each forming a note in a kinetic symphony that pulls the eye, the body, and the imagination. Some of these pieces are rare masterpieces, seldom available to the public to view.

Alexander Calder was an innovative sculptor whose work redefined the medium’s relationship to movement, balance, and light. He was born in Philadelphia in 1898, where the eponymous Gardens now reside.

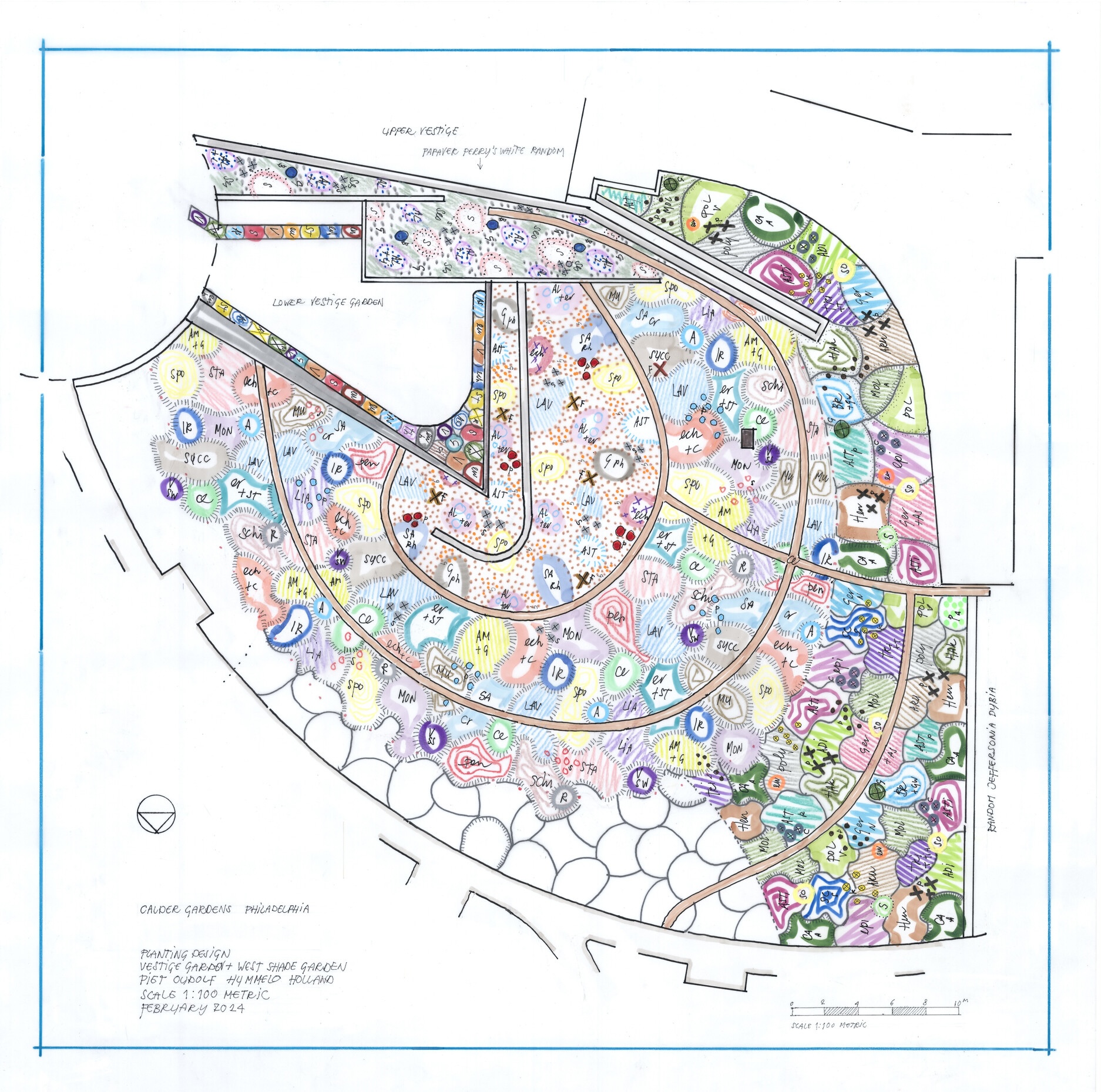

Calder Gardens, true to its name, unfurls a mosaic of art, architecture, and nature. Architectural lines by Pritzker-winning Herzog & de Meuron rise and dip, echoing the swoop of a mobile overhead. Piet Oudolf’s landscaping flows like liquid. Grasses brush ankles. Perennials punctuate paths in bursts of amber, violet, and ochre. Inside the 18,000 square foot Calder Gardens building—designed by Switzerland's Herzog & de Meuron and featuring two enclosed open air galleries—shapes in cobalt, scarlet, and jet black catch sunlight, casting flickering shadows on the floor. Every corner offers a new discovery: here, a suspended ellipse, there, a soaring archway. Each work is presented without a traditional placard, encouraging viewers to imagine and interpret each work on their own.

If you stand in one spot to peer at Calder’s 3 Segments (1973), the floating shapes and forms dance in defiance of your stillness, denying any restriction, any rules, any predispositions. “I have made a number of things for the open air: All of them react to the wind, and are like a sailing vessel in that they react best to one kind of breeze. It is impossible to make a thing work with every kind of wind,” he said.

The gardens themselves are alive: hedges meet spiraling steel, reflective ponds mirror arcs above, and paths curve and swell with purpose and whimsy. Architecture, plants, and art breathe together, echoing Calder’s Connecticut home while anchoring Philadelphia in a new rhythm. Every visit reshapes itself—never the same twice.

Wandering the winding paths of Calder Gardens is to discover a different side of Philadelphia—one that invites reflection, discovery, and engagement with both art and the environment. The meticulous geometry of hedges and stone contrasts with the playful unpredictability of Calder’s work, reminding visitors that even in a city steeped in history, invention and whimsy are never fully out of reach.