F L A U N T

Last Saturday, in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, a whiteboard sat humbly on the corner of Freeman and Franklin Street bearing a simple statement: “It’s in the Garage.” It’s colloquial, informal, a phrase tossed off in reference to an old TV or box of hand-me-downs. Behind the board is the roll-up door, closed to keep out the December chill. Enter through the side, however, and you’d find a warm-lit space, a crowd of young Brooklynites chatting and sipping natural wine, a live jazz band in the center of the room. Hung on antique doors and atop pedestals, leaning against car lifts housing vintage Jaguars and Fiats, are works of collage, painting, drawing, sculpture and installation from artists An Pham, Natalie Jacobs, Sara Erenthal, Lucia Gallipoli, Leslie Olivos, Sanya Bery, Lora Yip, and photographer Justine Kurland.

It’s in the Garage: A Multimedia Exhibition of Things We Choose to Return to & Leave Behind is Brooklyn’s latest DIY exhibition, a pop-up fundraiser from curating team Sanya Bery and Maria Noto. Housed in the Goose Garage, a working vintage-car restoration space recently doubling as a local community hub, the exhibition takes themes of neglect, return and sentimentality and renders them literal, housing them in a space where items are classically cast off to accumulate dust — not thrown away, but stored indefinitely — and turning that space into a site of communion and celebration. Its themes extend to a global scale: in recognition of “the material reality of return as a political condition,” all proceeds directly support students in Gaza paying for higher education.

Before the political, however, the idea for the pop-up began with the personal. “I went through heartbreak a couple months ago, and I found myself stuck on the idea of return and abandon: what parts of yourself you return to when a relationship ends, what parts of the person you choose to carry with you, and what you decide to leave behind,” Bery said. “I couldn’t unsee it, not just in my own life, or in the lens of love, but in all the ways we’re in this constant recycle of return, revisiting, rebirthing, releasing. Every time I read something, listened to music, or even took the subway to work, it kept showing up.”

Bery and Noto, friends and collaborators since their freshmen year at Wesleyan University, first visited the Goose Garage for a Climate Week dinner a friend was hosting, a stylish candle-lit affair with black-and-white film projections and farm-to-table food. When Bery returned the next day, it had been restored to its working form: boxes everywhere, people walking by, cars coming and going for repair. “It was this really fun aha moment,” she said. “I could suddenly see a whole showcase there.” She called Noto, who immediately understood the vision: “It’s a chameleon space. That sense of transformation is what really sparked everything.”

The two also set out to create something in opposition to a model they saw as inaccessible and limiting. “The art world often feels like it's built around this white-walled gallery model that's designed to keep people out so others can stay in,” Noto said. “And just like art, fundraising, especially in the art world, can be really restrictive.” The exhibition was designed to directly push back on those ideas, Bery said. “I have this poster on my wall from Bread & Puppet called the Why Cheap Art Manifesto, and it’s something I genuinely live by. Art isn’t meant to be a privilege. And you don’t need to be some extremely wealthy or well-connected person to take care of your community or extend support outward.”

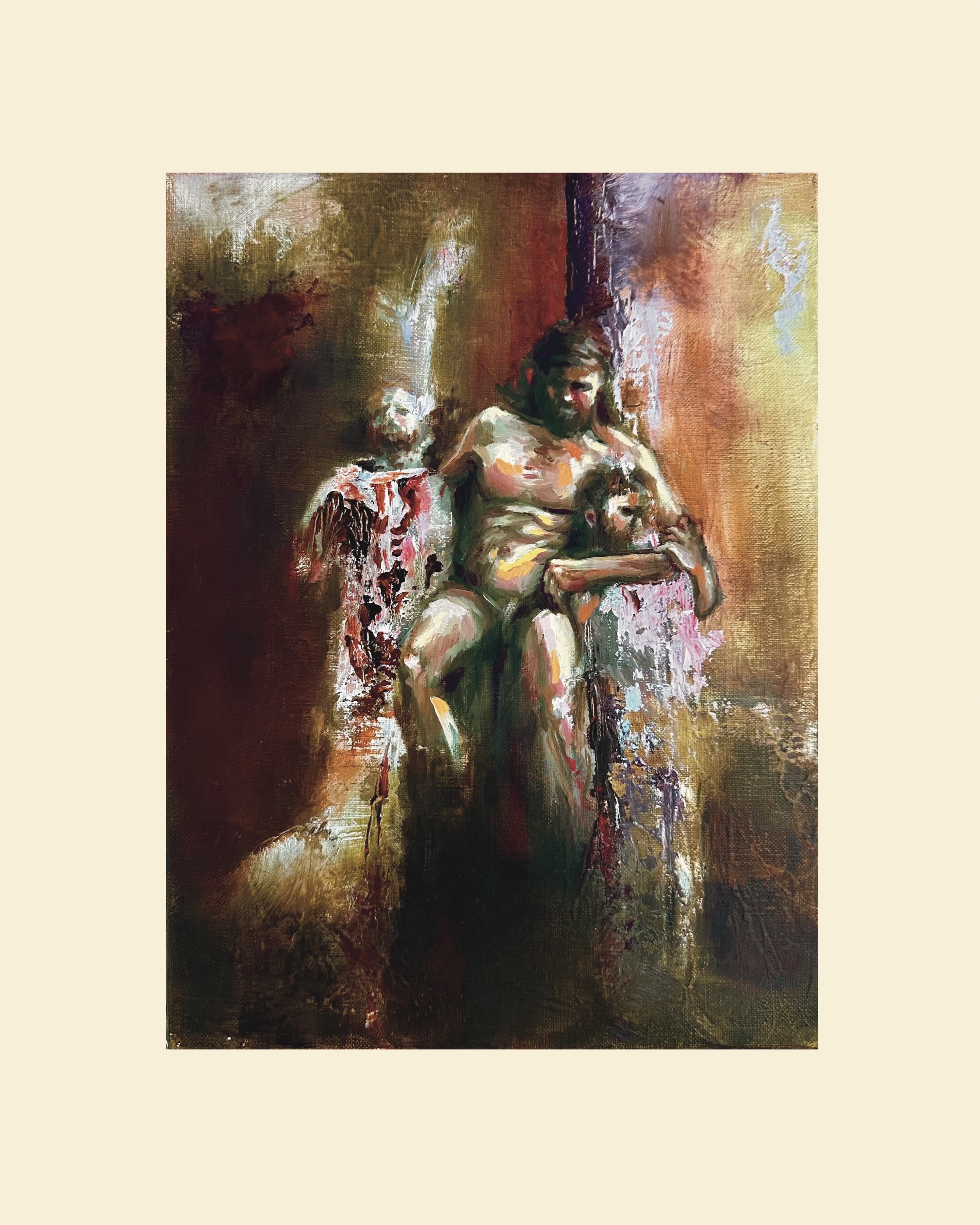

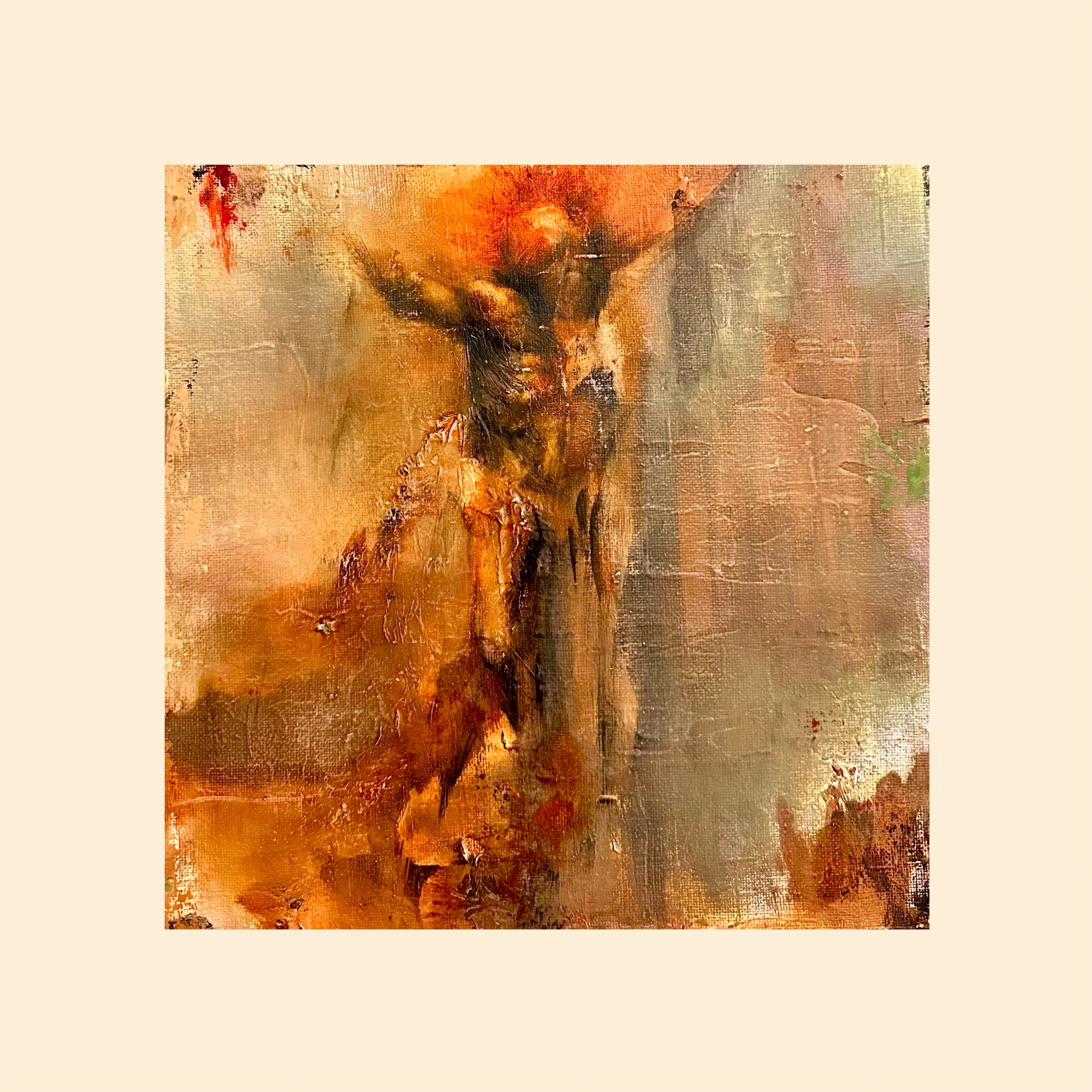

This ethos was a key draw for a number of the artists, including artist An Pham, who contributed five new paintings to the exhibition. “I feel like a lot of the reasons I haven't been making art very actively the past couple of years is because of my understanding of the art world…the market of it, the parts of it I don't feel like I agree with ideologically,” they said. “[It’s in the Garage] bridges that gap for me, to create work for a cause that I ideologically support.”

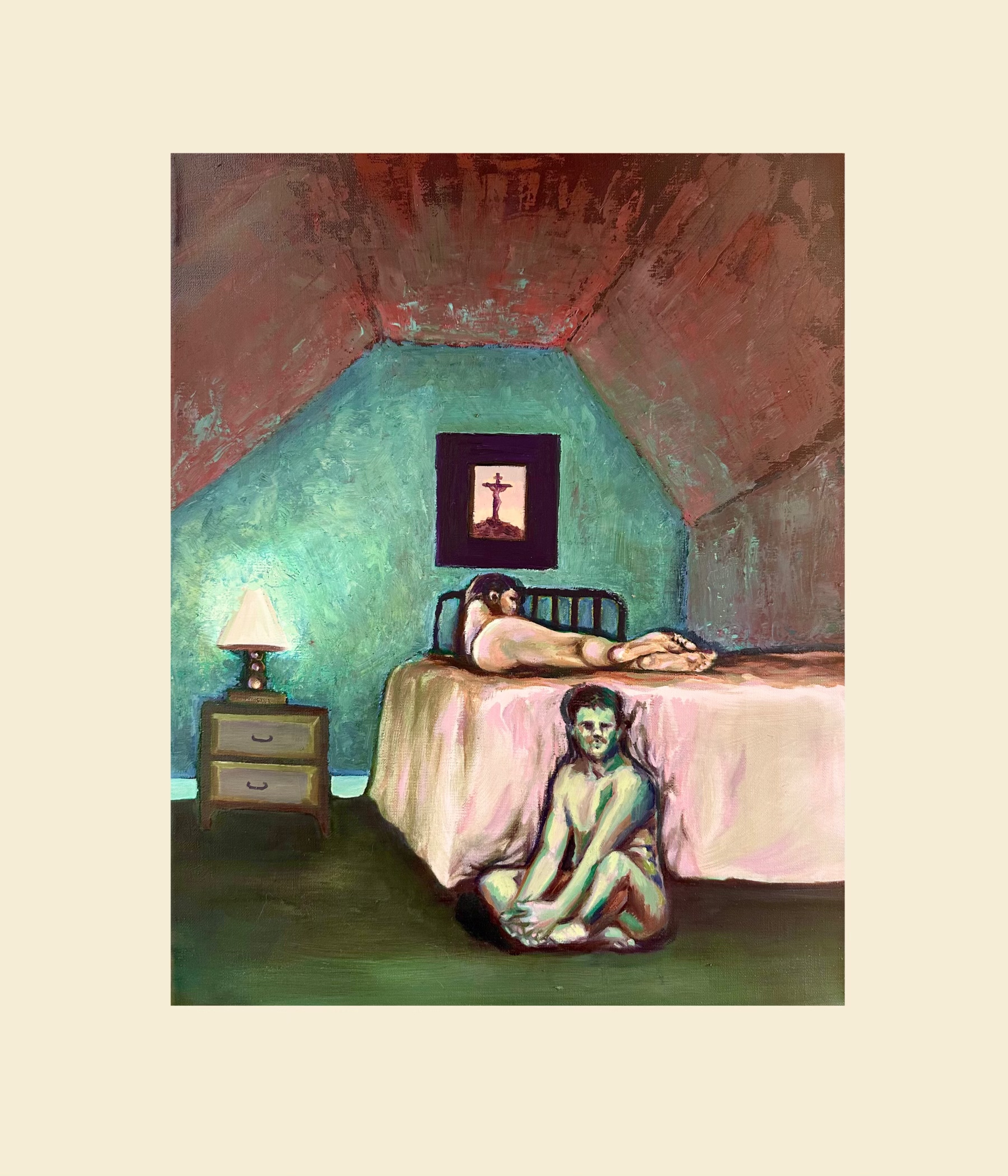

Pham’s five-work collection, One with Him (2025), revisits the crucifixion imagery that first drew them to art as a child growing up in a strict Christian household in Colorado, raised by a preacher and a born-again Sunday school teacher. The paintings deconstruct the body of Christ, both physical and symbolic, examining how its imagery continues to command devotion, fear, and desire. Through varying levels of abstraction, the work evokes the fragmentation of memory and the opacity of faith. “It's fascinating to me the way this horrible, tragic thing can inspire so many feelings at once,” Pham said.

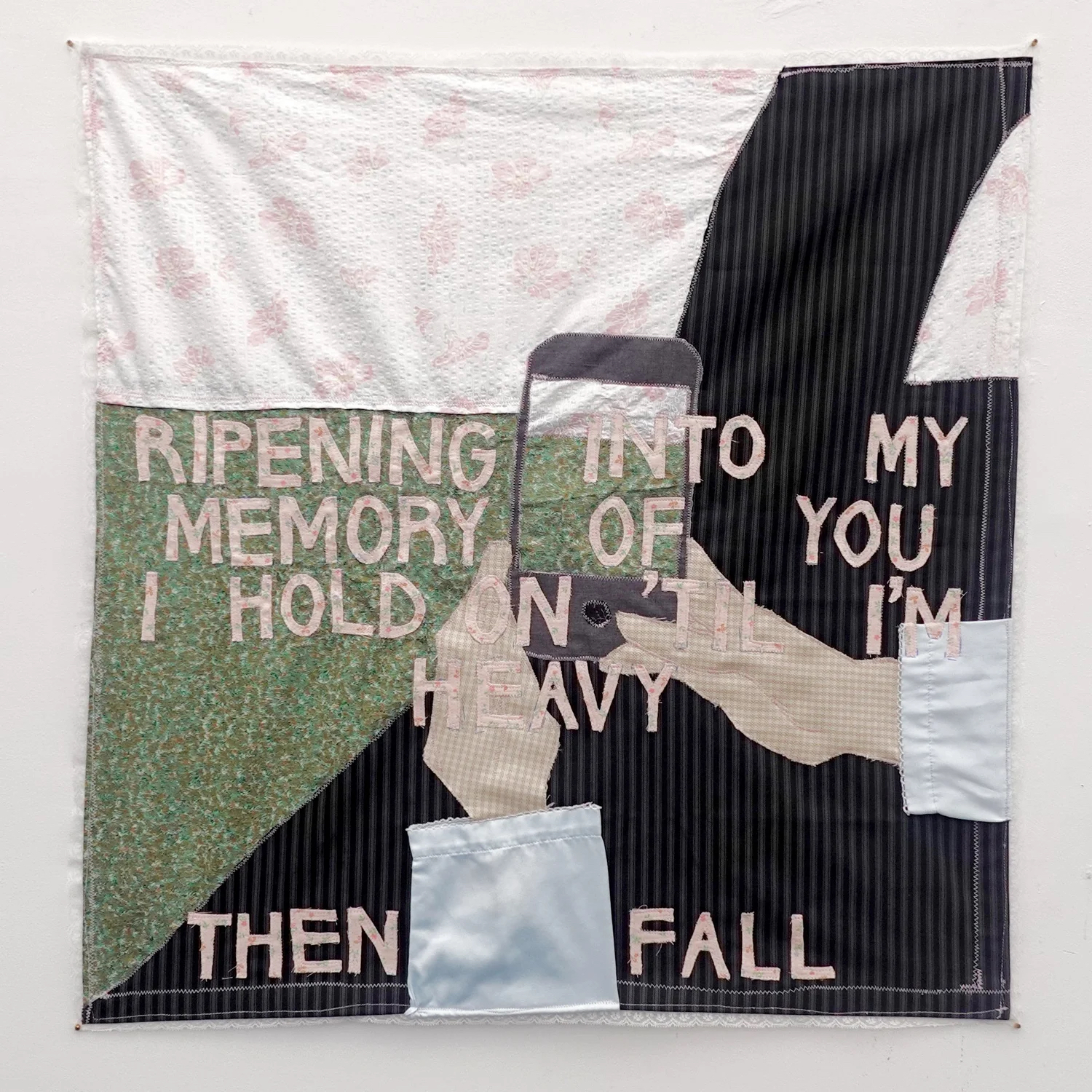

That tension in reflecting on personal religious history echoes in the works contributed by Sara Erenthal, a multimedia artist whose work has appeared across North America, Europe, Asia and Central America. Erenthal’s painting “The Holy Spirit” (2024) confronts her upbringing in an ultra-Orthodox Jewish community in Brooklyn. At seventeen, Erenthal escaped an abusive home to avoid an arranged marriage and spent a decade working odd jobs, eventually traveling the world and developing a daily art practice that began with the personal and over time shifted towards overt political messaging. “No Supper” (2024), Erenthal’s second contributed work, was inspired by a seven-hour detention following an action in Washington DC with Jewish Voice for Peace, the world’s largest Jewish Palestine solidarity organization. The cops processing the arrests, she observed, had nothing to do but sit at a long table, scrolling their phones, a scene that reminded her of the Last Supper. Erenthal’s practice, she’s said, functions as therapy to process a difficult past, and to empower movements for human rights.

Bery and Noto initially became familiar with Erenthal’s work through her public installations, murals and other visual works on old mattresses, dumpsters, and bus stops across New York, most of which have been dedicated to drawing attention to the crisis in Gaza. “Along with the visual impact of her work, we were really drawn to Erenthal’s voice and unique perspective, which aligned so closely with the mission of the fundraiser,” Noto said.

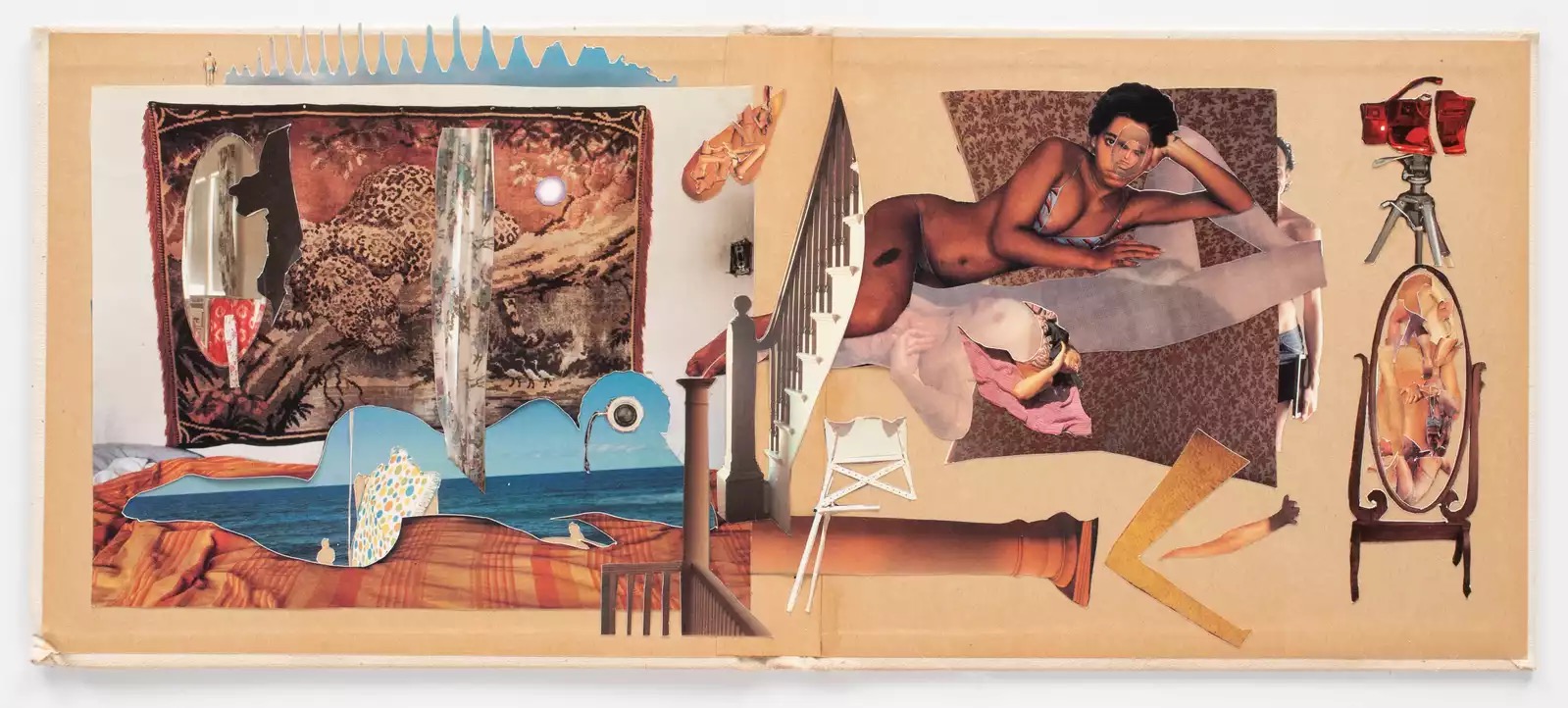

Most notably present in It’s in the Garage is “Cape Light” (2022), a collage work by multimedia artist Justine Kurland. Kurland, whose work is held in major collections including the Whitney, MoMA, and the Guggenheim, has been Bery’s favorite photographer since sophomore year of undergrad. “When this exhibition was still just an idea, Justine was always at the top of my list, not only because of what her work means to me personally, but because I see the concept of return as so deeply embedded in her practice.” Published in Kurland’s SCUMB Manifesto, “Cape Light” reclaims space within the male-dominated photographic canon by cutting, reassembling, and asserting new feminist possibilities through collage. According to Noto, Kurland’s agreement to participate shifted the entire exhibition. “Having such a highly respected and celebrated photographer involved allowed us to create a more fully realized, legitimized exhibition, one that could simultaneously spotlight emerging artists,” she said. “We’re incredibly grateful for Justine’s trust and support.”

The underlying cause of It’s in the Garage was a large part of Kurland’s decision to contribute. “I’m really hoping that [my work] and all the incredible artists in the show are able to raise some much needed funds,” she said via an Instagram post promoting the exhibition.

Over 80% of Gaza's schools have been severely damaged or destroyed. Twelve universities have been completely demolished, and more than 715,000 students are without access to education. For Bery, the cause was inextricable from the conceptual framework. “There is a poem I think about a lot, called ‘If I Must Die’ by Refaat Alareer, a Gazan poet and professor who was killed in 2023. It basically begins as, ‘If I must die, / then you must live / to tell my story.’ That thought has stayed with me, especially as we’re living in a moment where so much extreme violence is happening at home and abroad.” The exhibition was imagined as a fundraiser from the start, Noto said: “We had been talking about the idea of return in a more metaphorical sense, but it felt impossible not to acknowledge it as a much larger legitimate political reality. As others are enduring such unimaginable conditions, the very least we can do is talk about it, bring attention to it, and start and keep the conversation going.”

Aside from the works, and the fundraiser element, the exhibition itself was meant to reflect its mission statement: an accumulation of community, and an accessible place to spotlight emerging artists. “Maria and I have a really lovely friendship. It’s deeply nurturing, and we’re always taking care of each other,” Bery said. “My biggest hope was that the event would feel like an extension of that love and care. That part kind of unfolded naturally, through the people we met while creating the exhibition and then through everyone who showed up.”

The exhibition remained open throughout the day Sunday, after which the garage transformed again, back to its original form. Still, in two short days, It’s in the Garage managed to prove that art spaces can be organized around access rather than exclusivity, and that effective fundraising can happen collectively and on a grassroots level. “We were blown away by how excited people were about the exhibition and how many people showed up,” Noto said. “The artists we were able to showcase, and the exhibition itself, completely exceeded our expectations. We’re definitely interested in doing something like this again.”