F L A U N T

Every city has scars. Some are freshly scabbed over, others sublimated into the cityscape itself, nearly invisible—relegated to memorial plaques, revealed through winced expressions. No matter how faint, there is no question, though, that busy street corners full of everyday encounters,and sidewalks eroded from the running, stomping, and dragging of feet hold collective memories we pass through every day.

For Berlin-Hong Kong artist Isaac Chong Wai, these infrastructural fissures were impossible to ignore. Stories of bullet holes left around his birth city in the wake of the 1941 Battle of Hong Kong occupied a great deal of his imagination—in particular, a tiny crater left from the battle, now on the paw of a lion statue nicknamed Stephen that stands outside the HSBC building. The mark lived as a rumor in his mind, a missing space he couldn’t quite name.

This emptiness is one of the quiet anchors of CAREFULLY, Chong’s second solo exhibition at Blindspot Gallery in Hong Kong, on display through this fall. Across mediums like neon signage and video performance, the artist traces how memory lives in the body, revealing itself in the way people move through communal spaces with bruises or subtle glows. When moving among others, how can one fall carefully?

“Life always seemed focused on the future in Hong Kong,” Chong says of a particular work, “Missing Space (Hong Kong).” “The past and history received little attention.” So he began the search for these crystallized voids, and found them scattered across the city, casting the bullet holes in glass. The work resulted in this piece—each bullet hole reappearing as a fragile crystal resting between a sheet of glass and a mirror, the GPS coordinates etched neatly on top. Acts of violence become a small, shimmering absence in Chong’s reflections on communal memory. “What were once violent, fragile imprints are transformed into crystallized forms,” Chong says. “Memorials that preserve the past while inviting reflection.”

Another corner of the artist’s latest exhibition features two neon signs pulsing across from each other. The words “falling,” then “falling carefully,” and finally “care” move in rotation across one wall, while the same words are mirrored in a neon sign on the adjacent wall, translated into Traditional Chinese. The light pulses as the words displayed shift, moving from an urban warning toward communal consolation.

“This bilingual presentation reflects Hong Kong itself,” Chong says. “A city where traces of British colonial history coexist with Chinese language and culture in public spaces.”

The act of falling, losing control of one’s limbs and shifting your perspective, is more than a motif for Chong’s work. Years ago, the artist was assaulted on a street in Berlin, struck in the face with a glass bottle. The bruise that spread across his cheek formed the shape of a smiley face, grotesque and ironic at the same time. Through the lens of his own attack, Chong used creative practice to look out at a larger problem of rising anti-Asian sentiment in the wake of COVID-19.

This line of thinking circled through Chong’s artistic practice, becoming the basis for “Falling Reversely (2021/2024),” a performance piece shown at the 2024 Venice Biennale. Dancers studied CCTV footage of anti-Asian attacks, alongside Chong, slowing and reversing the motions until each fall lives inside their own bodies and becomes a shared choreography of sprawled limbs and flying hairs. “The work reclaims the body from the detached gaze of surveillance, turning repetition into resistance and visibility into protection,” he says. In the exhibition, the neon works take this logic of movement and translates it into light, cycling phrases of a soft pulse that fades between caution and warmth.

Chong often describes memory as a push and pull, an internal choreography of remembered potency and fading outlines. This thinking rings true in his ongoing series Breath Marks, etchings that trace the artist’s breath across panels of glass to create abstract figures, with photographic prints displayed behind them revealing each silhouette. In “Breath Marks: Queen Elizabeth II and Crying Hong Kong Girl (2023),” the artist reimagines a viral photo of a young woman grieving the queen’s death outside the British Consulate in Hong Kong. “She had never lived through colonial Hong Kong, yet her grief became a shared image across the internet,” Chong shares.

The artist also reflects on his own memories of British interventions in Hong Kong through the companion piece, “Breath Marks: Princess Diana and the Walking Stick (2025),” which captures the moment Diana bent to help an older woman retrieve her cane during a visit to Hong Kong in 1989. The artist recalled a childhood awareness of the deep communal love for Diana, as an acknowledgment of her resistance against the colonial structures she came from. “Through breath, I revisited that image not as nostalgia but as a gesture of care,” Chong posits. This, alongside the knowledge that Diana’s passing and Hong Kong’s sovereignty both occurred in 1997, creates a cataclysm of memory folding in on itself.

“Through my work, I try to slow down what the internet accelerates—to give weight, breath, and care to what might otherwise disappear in a scroll.”

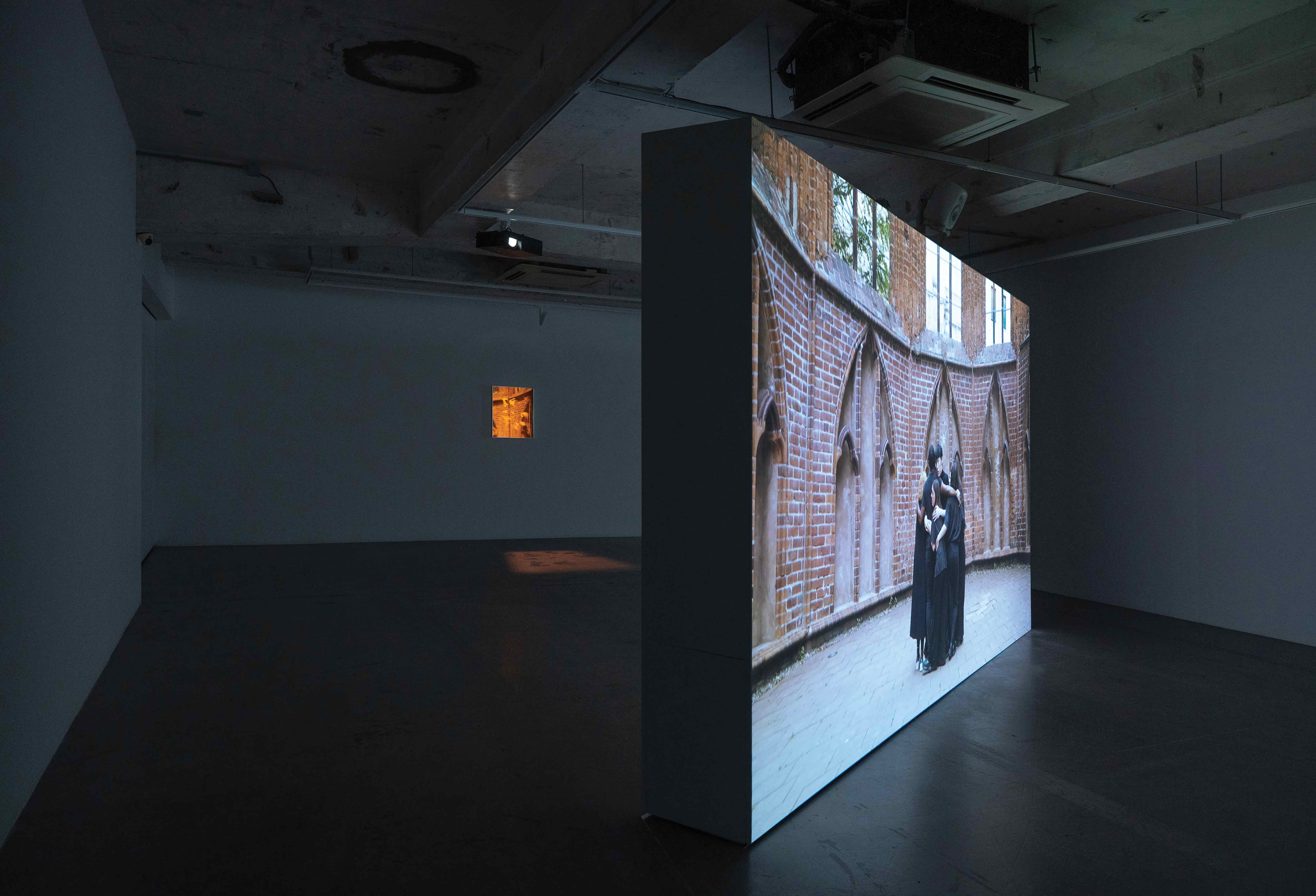

Chong pulls upon this background as video and performance meld in “Die Mütter (2022),” a two-channel video installation showing performers in a close huddle, singing lullabies and turning clockwise. Throughout the piece, performers pull out of the huddle and leave, the revolving motion mimicking time’s impression on our most intimate relationships to ourselves, our family, and our greater community. The video was inspired by Käthe Kollwitz’s 1920s woodcut of the same name, depicting mothers huddled together in the wake of death after war.

“Some performers step out of the circle, embodying absence and loss, while others remain entwined, creating a fortress of embrace,” he says. “The performers’ movements and songs offer a space for shared reflection, mourning, and care.”

Moving through rooms of drawings, flashing light, and video projection, viewers sense how movement and memory loop through Chong’s work. Exhalations from performers mimic the artist’s glass etchings of his own breath, and synchronized motions pulsate as the neon flickers at a steady heartbeat. Emotions move from the deeply personal to the outside world, urging attention to the wounds of history in the neighborhoods we live in and walk through every day. “Carefully is an adverb,” Chong asserts, “It shapes how we move, act, and even think.”

Walking by a piece like “Missing Space,” audiences may glimpse their own reflection. As fragments of glass and neon signs glimmer, the word “carefully” lingers as a quiet instruction, something carried back into the streets, somewhere where the city’s scars continue to heal beneath our feet.