F L A U N T

For centuries, humans have battled and embraced their bodies, working and hacking tirelessly to achieve some prescriptive perfection—though that perfection isn’t what makes a person whole. Rather, a fully-fledged human being is smithed through experience and influence over the course of a life. The self exists in a constant state of creation.

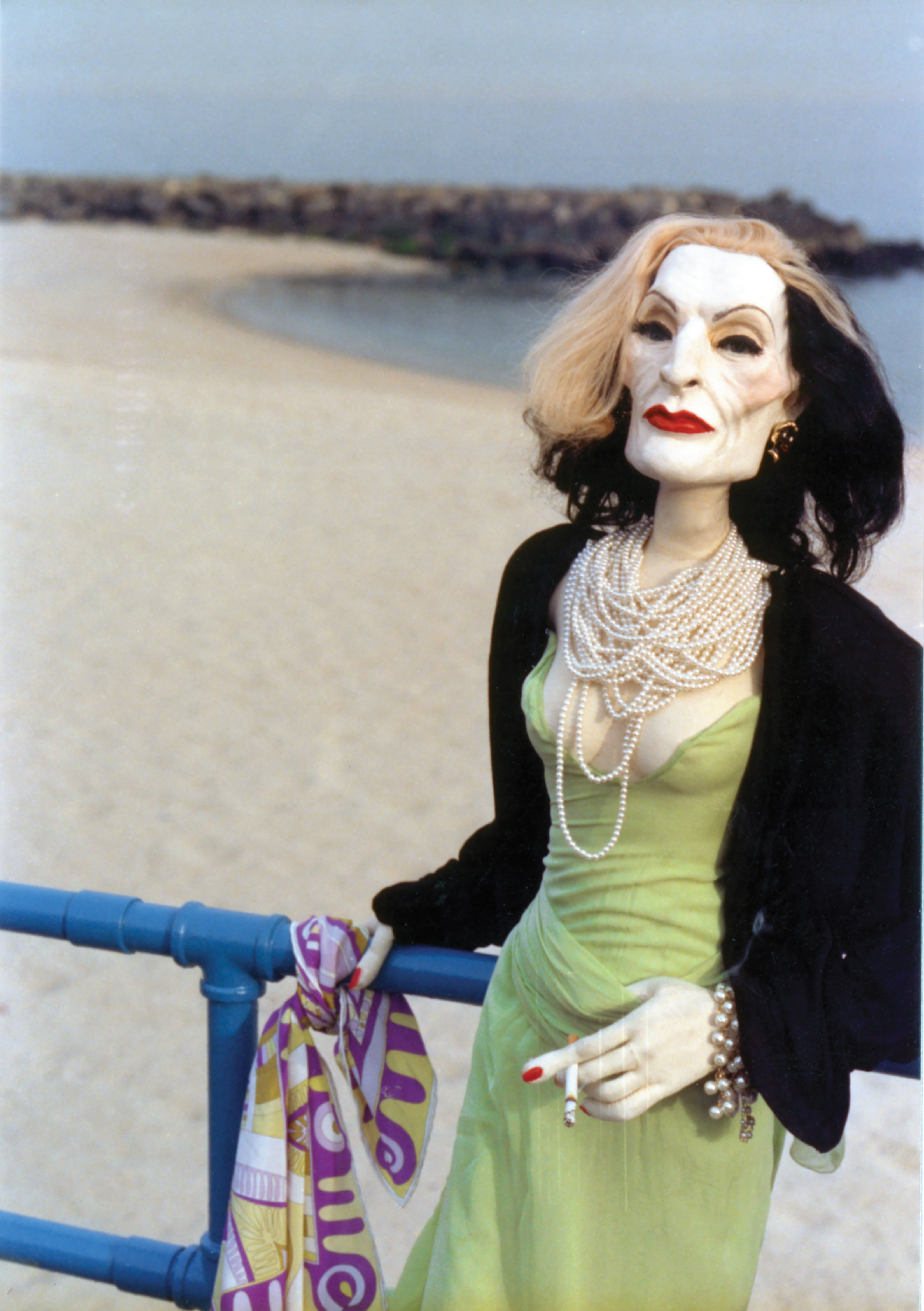

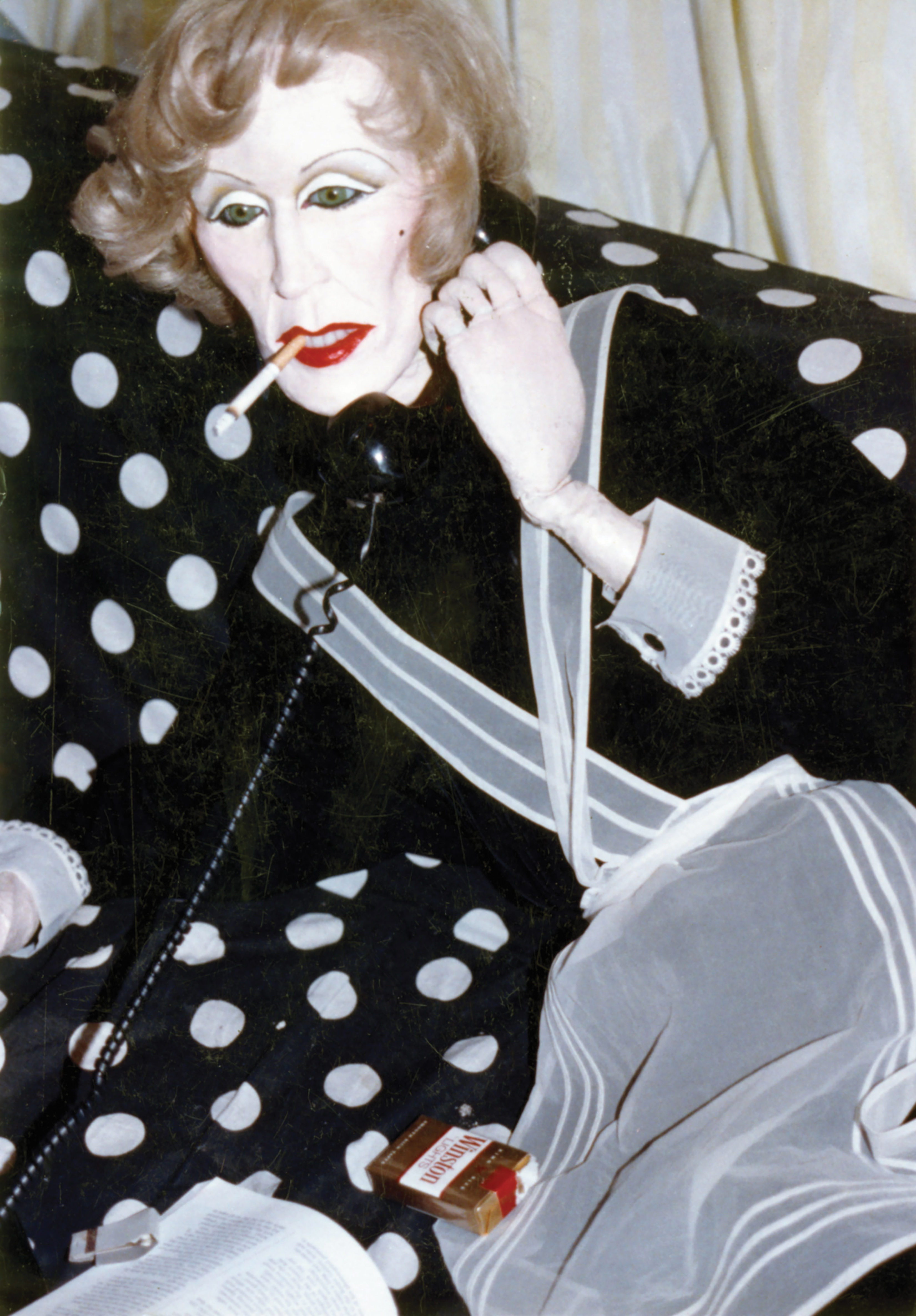

Visionary trans artist Greer Lankton defined the East Village art scene of the 1980s through explorations of her own loaded relationship with her body. In the first monograph of the artist, titled Greer Lankton: Could It Be Love, edited by Francis Schichtel, Jordan Weitzman, and Nan Goldin—and available via Magic Hour Press—this reckoning presents 100 photographs alongside a complementary essay by critic and friend Hilton Als. Lankton’s lifelike doll sculptures (crafted from wire and plaster and sometimes with eyes borrowed from a 31st Street taxidermist) are posed and photographed by Lankton herself; captured in their element—whether it’s curled up with a pack of Winston Lights, on the stoop with a canine companion, or schmoozing at parties with old friends.

Lankton, the daughter of a Presbyterian minister, was the human maker of a slew of beautifully grotesque and often ladylike dolls, crafted over the course of nearly 30 years. Her creations began as the twisted hollyhocks a 10-year-old Lankton molded to resemble a human form, and evolved into intricate, visceral, life-imbued dolls that appeared to be shaped and worn by the outside world; their humanity seeping through their seams. Raised in a home devoted to a Christian creator, Lankton became a creator herself, making art in her own image, and in the images that surrounded her. The artist’s work is a feat of emotional processing, as well as one of world-building and reflection.

In the age of artificial intelligence and online personas that seem to supplant real-life ones, it gets trickier to discern between a living, breathing human and a well-crafted doll. None of that existed during the years Lankton’s dolls were created, but her work remains eerily relevant in today’s internet sphere. Despite the uncanny valley fakeness that is often associated with dolls, Lankton’s works seem larger than life. The figures, though static, appear to be caught mid-motion, transcending today’s complexly characterized and splintered expressions of self.

Nevertheless, the audience peers in. The dolls don’t care that you’re there; they might not even notice. They twist themselves into lissome, acrobatic poses, inspired by Lankton’s training in ballet and gymnastics as an adolescent. In every bearing, expression and outfit, Lankton’s experience and perspective shine through.

Lankton’s world is not one of imitation, but of revelation—a mirror cracked just enough to show the truth beneath the gloss. Her dolls breathe with the same uneasy vitality we do, their plaster skin holding the tension between beauty and distortion, control and surrender. In them, we see the body not as an endpoint but as an ever-evolving thesis: stitched, molded, undone, reborn. In a digital era where identity is filtered and flattened, Lankton’s work pulses with something defiantly analog, defiantly alive. The body—hers, ours, theirs—remains both masterpiece and battleground, forever whispering the question: Who made me, and what am I becoming?