F L A U N T

In the world of nightlife, it’s easy to confuse volume for vision. Lights flash, bass drops, and the crowd moves—but the architecture of the experience swiftly disappears in the moment. For Mo Laudi, that invisible structure is the work itself. Long before the music begins, he is mapping a sensory terrain, arranging sound, light, and space not for spectacle, but for tangible meaning.

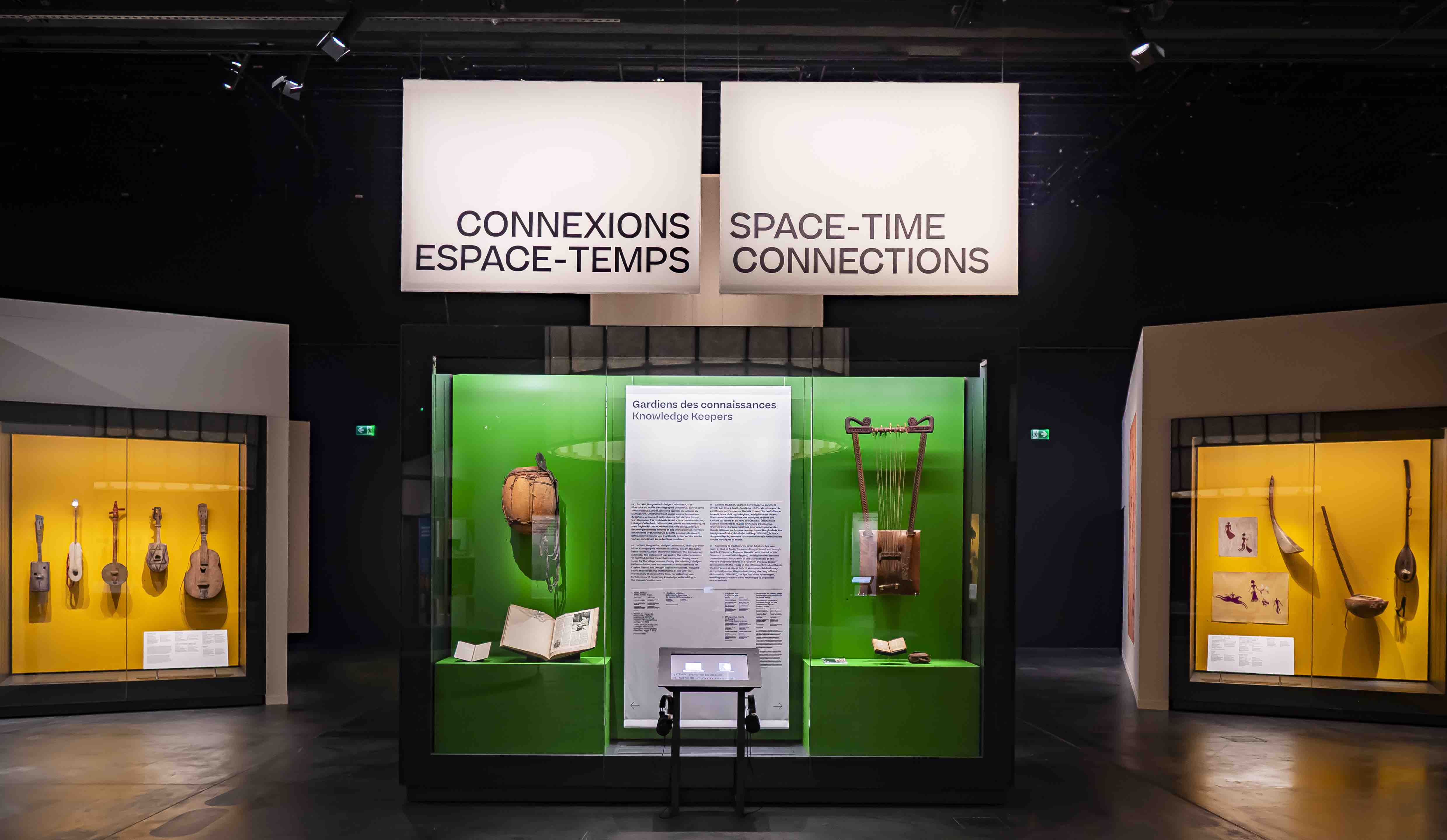

In Fara Fara, he brought Carsten Höller’s immersive installations into dialogue with African sonic traditions, treating rhythm as memory and melody as communal archive. In Afrosonica – Soundscapes, co-curated with Madeleine Leclair, he charted a living map of African and diasporic sound, from Congolese rumba to experimental electronics, extending hospitality beyond the museum walls.

He calls it a composition, built from fragments—sounds, images, ideas—arranged into constellations. Guided by his Globalisto philosophy, which draws from African knowledge systems, post-apartheid transitionalism, and radical hospitality, his curatorial work resists borders, whether geographical, disciplinary, or ideological. In his hands, heritage isn’t fossilised; it’s kept in motion, carried into the future without losing its roots.

Mo Laudi’s curatorial work serves as a cartography of Black and diasporic sound, a meeting point for traditions, experiments, and imagined destinations. Here, the crowd still answers—but the loop is slower, the reverberations longer. And whether in a gallery, a public square, or a DJ booth at a biennale opening, his mission remains the same: to listen deeply, to shift narratives, and to create spaces where the world can imagine itself otherwise.

You’ve been widely regarded as a DJ, but your work clearly transcends that title. How would you describe your curatorial identity today, and what do you hope people understand about your work beyond music?

I see my curatorial identity as a form of composition. Whether I’m in the studio producing, on the decks, in a gallery, or in a book, I’m working with fragments, sounds, images, ideas, stories, and arranging them into a constellation. My foundational worldview is largely informed by the Globalisto philosophy, which is based on African knowledge systems, Botho, post-apartheid transitionalism, radical hospitality, and a willingness to unlearn, aiming to envision a borderless world. The DJ booth taught me about flow, about the journey, about how sequences can carry people somewhere unexpected. In curation, I work with the same sensibility, but the tempo is slower, the textures more layered. My work is about listening, to people, to spaces, to histories. Music may be the entry point, but the journey moves through visual art, architecture, politics, ecology. I’m not only concerned with what we hear, but also with how we inhabit space together.

What drew you into curating Fara Fara, and how did you approach bringing Carsten Höller’s work into dialogue with African musical and cultural contexts?

I was invited to curate Fara Fara by my friend Anna-Alix Koffi, the founder of Something Art Space in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire. We had been speaking for years, and during Art Basel we met Carsten Höller for lunch at Hôtel Costes. I immediately connected with him, I had long admired The Double Club, his 2008 London project that fused Congolese and Western cultures in equal measure. The film Fara Fara, conceived in 2014 and shown at the Venice Biennale curated by the late Okwui Enwezor, became the seed. From that lunch, the idea for Fara Fara, Höller’s first solo exhibition in Africa, took root.

What drew me in was that magic space where music becomes more than music, it becomes a conversation between worlds. Höller’s work does exactly that: conceptual, playful yet serious, immersive, and deeply concerned with perception. In Abidjan, I wanted to place his practice in resonance with African sound traditions that also alter perception—not just as an aesthetic gesture, but as a way of thinking sonically.

For years, Höller has been in conversation with Africa—he built a remarkably brutalist home in Ghana, and, being born in Belgium, he grew up with connections to African communities. This exhibition was important because it allowed those connections to be reframed through the lens of African musical epistemologies, where syncopated rhythms and melody are not entertainment alone, but repositories of memory and communal imagination. By situating his work alongside these traditions, Fara Fara became not only an exhibition, but a space where sonic heritage could dialogue with contemporary art on equal terms, shifting the dominant narratives of how Africa and Europe encounter each other in art history.

As someone who is constantly moving between disciplines—music, curation, writing, installation—how do you see your role evolving in the coming years? What can we expect to see out of your curatorial journey?

My role is moving toward building spaces where disciplines blur completely. The separation between a DJ set, an exhibition, a lecture, a public sculpture, and a performance is becoming less relevant to me. I want to create environments where scholarship is danced to, where archives sing, where exhibitions have the same unpredictability as a live set.

Globalisto will continue to be a living philosophy, not just in galleries and museums but also in classrooms, shaping curriculum in South Africa and beyond—inviting students to think, move, and create across borders. Expect more collaborations, more cross-continental dialogues, large-scale public artworks that double as gathering spaces, and works that are alive—changing with each encounter.

The vernissage is a ritual—it sets the tone. For Fara Fara, a speech would’ve been a pause; music was the current. A b2b set turned the opening from observation into participation, collapsing the distance between artist, curator, and audience. The Fara Fara opening featured a b2b DJ set by Arman Naféei and Raoul K. Ever since stepping into this work, I’ve treated the vernissage as a way of bringing people together: where some see networking, I see human connection. I’ve been invited to DJ across the vernissages at biennales—Berlin (by Gabi Ngcobo and Kader Attia) and Venice (for the South African and British pavilions, among others)—and I’ve shown installation work at Dak’Art Biennale in Dakar (Senegal). Time and again, sound gathers strangers into a temporary community.

Much like a DJ, a curator selects, sequences, and creates a mood. What’s the difference between curating a dance floor and curating a gallery, and what do they share?

On the dance floor, the crowd answers in seconds; in the museum, the loop is slower but just as intense. Both demand deep listening—to frequency, rhythm, space, architecture, and flow—and the trust to guide people between the familiar and the unknown. Club time is collective and embodied; gallery time is individual and reflective, but the aim is the same: transformation. DJing and curating are acts of selection and sequencing entangled with the politics of representation. As Arthur Jafa put it, “Marcel Duchamp is a DJ”, the ready-made remix. From diasporic bricolage to institutional canons, both practices can reproduce power or resist it. I treat curating, like DJing, as a practice beyond the museum: sampling histories, subverting dominant narratives, and opening new paths for shared meaning.

You referenced the UNESCO recognition of Congolese Rumba. What role should curators play in protecting and/or spotlighting intangible cultural heritage through contemporary art?

Heritage is not a museum piece; it’s a living rhythm. The danger is that recognition can fossilise a form, freezing it in an “authentic” moment. Curators can act as translators, creating contexts where heritage continues to breathe and evolve. That means commissioning works that draw on traditions without locking them into nostalgia, and ensuring the custodians of those traditions are central to how they are represented. There are many styles of music still to be recognised and protected, I could even think of Amapiano or Afrohouse, being in the same realm.

Fara Fara was deeply site-specific, but also global in its scope. How do you negotiate your role as a South African curator working with a European artist in West Africa, without flattening context or falling into spectacle?

It’s about humility and listening, the kind that shifts your centre. I enter as a guest, even when the rhythms feel close. Context isn’t fixed; it breathes, it moves. I work by being in conversation with local practitioners, historians, musicians, cultural workers , not as consultants or audiences, but as co-authors. I’ve been to Abidjan a few times — playing at Bushman Café, at Afro Chic — feeling the city’s pulse in places that are more than venues, spaces where food, books, music, and memory sit at the same table. SOMETHING art space is part of that same current, a place that gathers the world without losing its ground. I think about the work of Bisi Silva, Koyo Kouoh, Ibrahim Mahama — how they built spaces with their own hands, how they made institutions that answer to the people who live with them. That’s the current I move in: we don’t wait to be given a place, we make our own, and in doing so we create our own world — one that holds the dialogue between the local and the global, and keeps all its intricacies intact. With Fara Fara, the site-specificity came from being in that dialogue — listening to the city, its histories, its voices — so the work could travel without leaving itself behind.

You’ve said that rest, healing, and deep listening are central to your work. How do you protect these values in your curatorial practice?

Rest is political. In a world obsessed with speed, relentless production, status, and material accumulation, rest becomes a form of resistance. I often think of the rest note in music — that pause, that silence — as a metaphor for the unseen, the unrecorded, the unspoken. Healing begins when we slow down enough to hear what is unsaid. Deep listening, for me, means creating exhibitions that are not overloaded — spaces that allow for breath, for contemplation, for a kind of listening that extends beyond the audible. I protect these values by pacing projects sustainably, by building in moments of quiet, and by resisting the pressure to always be “on.”

My Rest paintings are part of this practice. They are multilayered works that reference silences in history and the archives — the silences we keep, the silences we are complicit in, the quiet that surrounds so much loss. They are meditative spaces that invite reflection and questioning, yet abstract enough to allow each viewer to find their own meaning. In that way, rest becomes not an escape from the world, but a way of returning to it with greater care and attention.

You described Afrosonica as a space of radical hospitality. How do you curate hospitality? What does care look like in the context of an art exhibition?

Hospitality is about who truly feels welcome—and that goes far beyond sending an invitation. It’s in the seating, the lighting, the accessibility, the way someone is greeted. In Afrosonica, hospitality meant making space for sonic practices that don’t always fit inside the “white cube” and creating an environment where audiences felt free to respond in their own way—dancing, meditating, or simply staying longer than they had planned.

Care in curation is about anticipating needs you may not share, and shaping an exhibition as a place of encounter rather than extraction. I was delighted when Madeleine Leclair invited me to co-curate the show with her and the museum. Hospitality, for me, included reaching out to my own community—Mother Dubber, Bintou from Radio Nova, Binetou from Def Jam West Africa—to curate playlists. This meant the exhibition continued to live beyond the museum walls, travelling into digital space and bringing in new audiences through their networks.

I often think about this in relation to my own story—having gone to Pretoria Boys High, the same school as Elon Musk, and realizing how we’ve moved in polar opposite directions in how we imagine the world. That awareness shapes how I think about inclusion and care.

One of the works in the exhibition, Lee Hirsch’s Amandla! A Revolution in Four Part Harmony, speaks to the sonic revolution of South Africa. Its presence felt even more poignant when, on the day Afrosonica opened, Donald Trump was claiming there was “white genocide” in South Africa and inviting only white refugees—citing Julius Malema’s singing of Kill the Boer, a song from the liberation struggle. Amandla! carries the deeper history of the freedom song—its role in uniting and energising communities during apartheid.

Through the Globalisto philosophy, I see hospitality as the work of seeking harmony in society—not as erasure of difference, but as the careful, active weaving together of voices, rhythms, and experiences so they can exist together in mutual respect.

The word Afrosonica itself suggests a new genre. What does this term mean to you, and what can it offer to the larger conversation around sound and Black cultural production?

I came up with the word Afrosonica, drawing on township vernacular, hip-hop heritage, Black sonic traditions, and the creolisation of languages—condensed into a new linguistic form: part Afro (Africa), part sonic, and part imagined destination. Afrosonica is a space where sounds, histories, and identities meet, merge, and mutate.It is a cartography of sound rooted in African and diasporic traditions, but not confined by them. It speaks to the political, spiritual, and aesthetic power of African sonic practices and their capacity to reshape global culture—reimagining the soundscape through works such as my compositions Daughters of the Dust, Sons of the Soil, and Congo Square in D-sharp minor, or KMRU’s Depot, which resist easy categorisation. It embraces field recordings, contemporary art, and experimental forms, moving away from formulaic pop structures to create a space that could indeed be a new genre.In the wider conversation on Black cultural production, Afrosonica offers a lens that is both historical and futuristic—honouring the ancestors while opening pathways to new sonic possibilities. It insists that sound is not merely an art form but a way of thinking, resisting, and imagining otherwise. Crucially, it also welcomes other perspectives—such as those of Midori Takada and Tarek Atoui—who may not be Pan-African in origin but whose practices are part of the Globalisto family, contributing to its expansive and interconnected vision.

Geneva, Afrosonica – Soundscapes fills the Musée d’ethnographie with a living map of African and diasporic sound. Co-curated with Madeleine Leclair, it brings together instruments, new compositions, field recordings, and contemporary artworks—creating a space where Sammy Baloji’s Congolese rumba flows into the electronic experimentation of DJ Lynnée Denise, Penny Siopis, and Venice Golden Lion winner Sonia Boyce; where the wind instrument breath rides the pulse of the club; and where ancestral rhythms Yara Mekawei meet the avant-garde of Simnikiwe Buhlungu.

Hospitality shapes everything—from how people enter the space, feel in the space to how they connect to Rohan Ayinde and Tayo Rapoport, Afrosonica is an archive in motion, a gathering point, and a place to listen with your whole body while imagining the sound worlds still to come.