F L A U N T

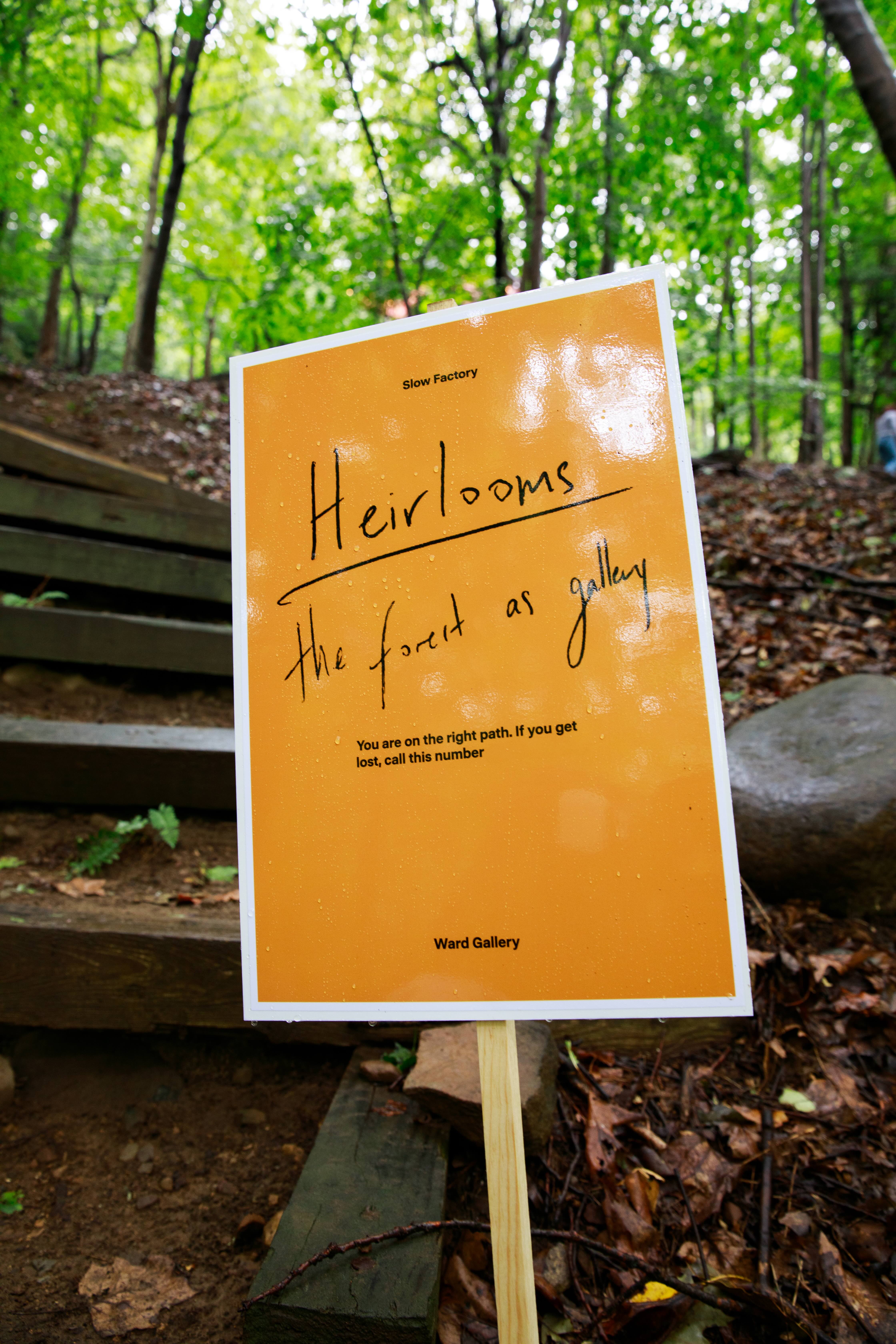

On a Sunday morning in early September, a full moon lunar eclipse was still barely visible in the late morning sky. It was on this Sunday that Slow Factory co-founders Celine Semaan and Collis Browne were joined by Ward Gallery co-curators Gabrielle Richardson and Saam Niami in presenting Heirlooms: The Forest as Gallery. Held at the Slow Factory Sanctuary in Nyack, New York—or Lenapehoking, the ancestral land of the Lenape people—Heirlooms served as both an art exhibition and sacred offering, transforming a small swatch of the forest into a living gallery.

It’s rather unsurprising that environmental and social justice organization The Slow Factory (which started as a sustainable fashion label in 2012 and has evolved into a sort of movement laboratory grounded in regenerative design, storytelling, and open education) collaborated with Ward Gallery (a New York City-based gallery known for championing talent outside of the hegemonic blue-chip space) for Heirlooms. There was a powerful synergy there—the energy in the air was not just intimate, but comfortable: like the warmth of sharing a meal with loved ones, or the kinship felt between those gathered around the same flame.

In preparation for the show, curators brought together a constellation of artists and scholars whose work and practices participated in beautiful conversation with one another: Vivien Sansour, Cassandra Mayela, Cara Marie Piazza, Carlos Agredano, Praise Fuller, and Nadia Irshaid, all exhibiting works that engaged with themes of ancestral memory, seed storytelling, regenerative food, material upcycling, and colonial violence.

Throughout Heirlooms, artworks were delicately installed upon tree trunks, suspended between branches, placed among the leaves, and even buried in the earth. Niami (co-founder of Ward Gallery,) states the show largely deals with “contextualization and inherited materials, both in the forest and in the historical city of Nyack,” and many pieces were made from found or repurposed objects, representing the physical materials. But we inherit so much more––memory and history, trauma and legacy.

Part of this reckoning with inheritance in the show came from the location itself. This forest, in particular, has sheltered the dispossessed and persecuted throughout its colonial history. Nyack was a key passage point for refugee slaves traveling North on the Underground Railroad. It is also the first recorded place where Black people owned land in the 17th century British colonies.

“In the midst of our country’s persecution of those seeking shelter and safety as well as our world’s addiction to resource and land theft, we are honoured to stage a community event on land that has, throughout its history, housed and protected people,” Semaan shares of the space.

Vivian Sansour is a Palestinian artist, storyteller, researcher, and founder of the Palestinian Heirloom Seed Library: a global initiative to recover heirloom seeds, preserve and share their stories, and put them back into people’s hands. For Heirlooms, Sansour and Joy from Saboon Maazeh brought 50 pounds of mulkhiyyeh, a beloved and meaningful crop in the Levant and across the SWANA region. Attendees sat on the earth while picking leaves from the heirloom plant, sharing memories, and arguing about family recipes. A question Sansour works with is: “How can we nourish ourselves, so that we can nourish others in a time of pain?” This also may be the charge of the artist.

The importance of this cultural preservation work only grows stronger under increasing colonial erasure and genocidal violence. On July 31, 2025, Israeli forces demolished part of the Union of Agricultural Work Committees (UAWC’s) seed bank in Hebron, the only seed bank in the West Bank, Palestine. This assault on Palestinian food sovereignty falls within a larger strategy of ecocide and cultural genocide. In this context, we can see how seed saving is a vital act of political resistance—so powerful that in 2021, Israel named the UAWC a terrorist group.

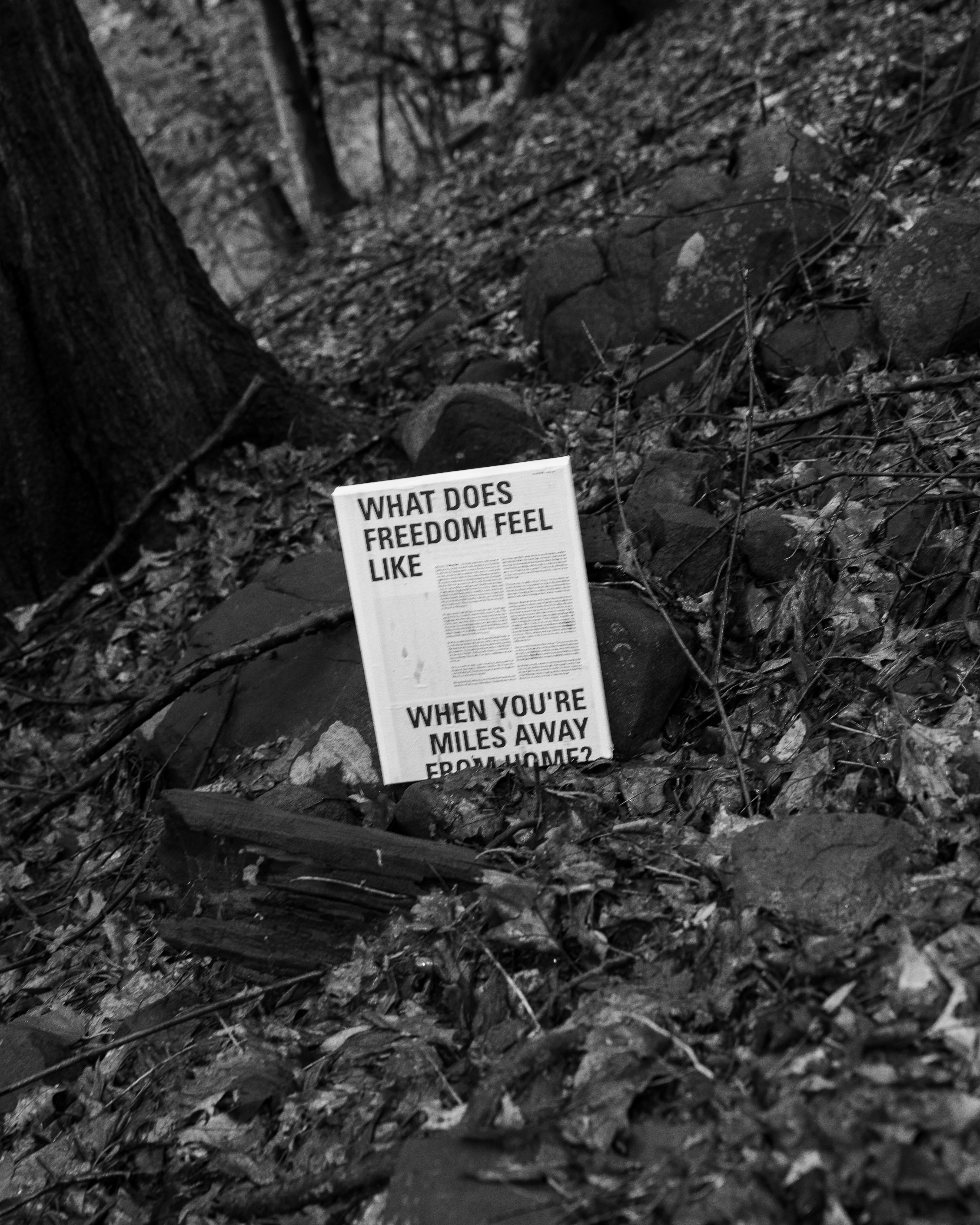

State power works to erase the stories and the bodies of those it deems expendable. This truth animates histories of resistance across time and geography. Praise Fuller’s “a shrine for self-determination” (2025) feels animated by this same truth. Fuller is a cyanotype artist, educator, and organizer from Houston, Texas. Community archiving and preservation is central to Fuller’s practice. Her installation for Heirlooms was a shrine to Black American resistance to enslavement and oppression: archival portraits of sharecroppers on a window, hanging at eye-level; a small cotton dress hanging on a neighboring tree, where a passing gust of wind may have filled the dress with life for a moment—though, for most of the time I spent with this piece, the dress was limp, empty.

And still, small mirrors dotted the surrounding tree trunks. When illuminated by natural light, Fuller’s windows and mirrors became portals. The viewer was pulled outside of linear time, away from static ideas of the past and future. We must confront our own systemic oppression and strive for self-determination, we must honor and learn from the past in order to realize a better future. The forest is a powerful location for us to think in new ways and to radically imagine: What would it feel like to be free?

Heirlooms felt antithetical to the traditional art world show. The presented artworks and workshops were rooted in ecological restoration, collaboration, and cultural healing. Staging these works in the forest allowed for them to be experienced without the physical and mental impositions of white gallery walls. A reminder of our collective capacity, Heirlooms gathered this group in ritual amid our decaying world, reclaiming nature as both sanctuary and stage.

Heirlooms: The Forest as Gallery is open by appointment only. join@slowfactory.com.