F L A U N T

It is pretty normal to take bodies personally; we live inside them, after all. Our bodies do stuff: move, breathe, excrete substances. Drip, writhe, and peel. To a large extent, we accept these human processes with minimal alienation from what is ultimately a series of fairly gross experiences. Living as we do in a media-saturated society, it is likewise pretty normal (and also pretty gross) to dehumanize bodies. We might watch them for entertainment in Marvel movies or pornography, or hyperfixate on certain parts of them for pleasure, or gaze in horror as they starve to death in Gaza before turning away to continue with our day.

It is less normal, though, to see bodies as a complete abstraction. That is more the purview of meditation masters, existential philosophers, serial killers—and maybe also multimedia sculptor Mire Lee. Born and raised in Seoul, South Korea, Lee has developed a highly abstract and sometimes literally fluid language of bodies in her sculptural work, expressed through matrixes of building materials, dripping glycerin, video feeds, and scrims of skin-like fabrics and dried industrial crust.

“When I was getting into an art school, it was still all about technical, representational skills,” Lee says, Zooming in from her studio in Amsterdam ahead of her first solo show in Los Angeles, Faces, set to debut at Sprüth Magers this September. “It’s changed a lot by now, [but back then] it was really about being able to make something to, you know, make a head of a Roman general, for example.”

Forced to choose between rigidly separated art departments and drawn into the sculpture department largely because of its lack of competition, Lee was initially unhappy about the very traditional program at Seoul National University, which focused on working with clay, stone, wood, and metal in repetition.

“I wanted to learn more exciting things, contemporary art and stuff,” says Lee. “I think back actually, and I really, really, really liked doing it. I loved all the technical courses and I’ve had a strong relationship with material ever since I was in art school.”

In 2013, as she chased her BA in Sculpture with an MFA in Media Arts, different materials began to creep into Lee’s practice. Wood, clay, and stone started to give way to plastic tubing, motorized components, poured concrete forms, videos made from original footage or spliced found imagery, and viscous, leaking liquids. The results vary widely, from a tangled mess of greasy hoses animated by a rotor shaft, to minimalist concrete monuments supporting embedded videos or slouches of hung fabric, to scrims of flesh-colored gauze, or construction scaffolding stretching thin skins to their breaking point—all of which somehow ends up more human than, for example, the disembodied marble head of a Roman general.

“I still actually use all sorts of traditional materials,” says Lee. “I think I even use whatever material in a totally traditional sense, even though it’s digital or mechanical, I like to treat them as something I can mend with and touch and put together.”

What seems to begin as material play, that Lee describes as largely eschewing intention or even thought, manages to build meaning through constraint.

“In the process of making works, I almost have no intention,” she said. “It just goes, or it does not go. What helps me most of the time is the limitation in the material, but also the limitation in space. Sculpture, I think, as a medium, has a lot of limits. You cannot alter it very easily, and it takes time and it breaks and it’s hard to transport and to situate something. Technical limitations help me.”

Though Lee describes this observation of rising to challenge as a driver for her work as “sort of banal,” there is perhaps a greater truth that underpins her relationship to constraint. Many aspects of Lee’s work are abstractly sexual to some degree; the writhing forms of tubing or plastic sheeting could be hysterical, or in pain, or decidedly in pleasure. The concept of lubrication is not exclusively sexual in nature, but always feels more or less adjacent to it. And Lee’s work frequently resembles or directly alludes to more extreme forms of sexual congress, including BDSM and suspension.

“I have a lot of sexual fetishism connotations in my work, and my work or myself, is largely influenced by subculture and pornography, as much as literature,” says Lee, whose titles variously reference Ophelia and Gertrude Stein, but might equally connote a sort of hormonally intense teen girl energy. That Lee finds a degree of transcendence within the material limitations of her sculptural practice mirrors the paradox of bondage as sexual catharsis: the idea that being literally constrained can be freeing and expansive.

In truth, the contrast between Lee’s subject matter and materials, and the context of her various installations form a central tension in her oeuvre—and perhaps exemplify a cultural bell curve of eroticism as artistic versus pornographic: For example, The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife (1814), the standout image in a three-volume book of woodblock-printed designs by Japanese artist Hokusai has crossed over from erotica into fine art, as has a similar image by Yanagawa Shigenobu from Suetsumuhana (1830), and even an array of erotic netsuke depicting cephalopod-based sex. These represent the fine-art end of a curve that also includes hentai and tentacle porn. As with Lee’s work, the division between high and low materials, elevated and base art forms, and elite and abject points of inspiration is more-or-less nonexistent.

“I have an old video work in the show that is a compilation of pornographies, but from only non-violent scenes of, like, portraits,” Lee says, referring to a work from 2017 that will be included in Faces, the forthcoming show at Sprüth Magers.“This was made directly after I had a three-months-long pornography addiction…but it’s a very quiet, peaceful video.”

“And then there’s a video of my mom sleeping,” she adds.

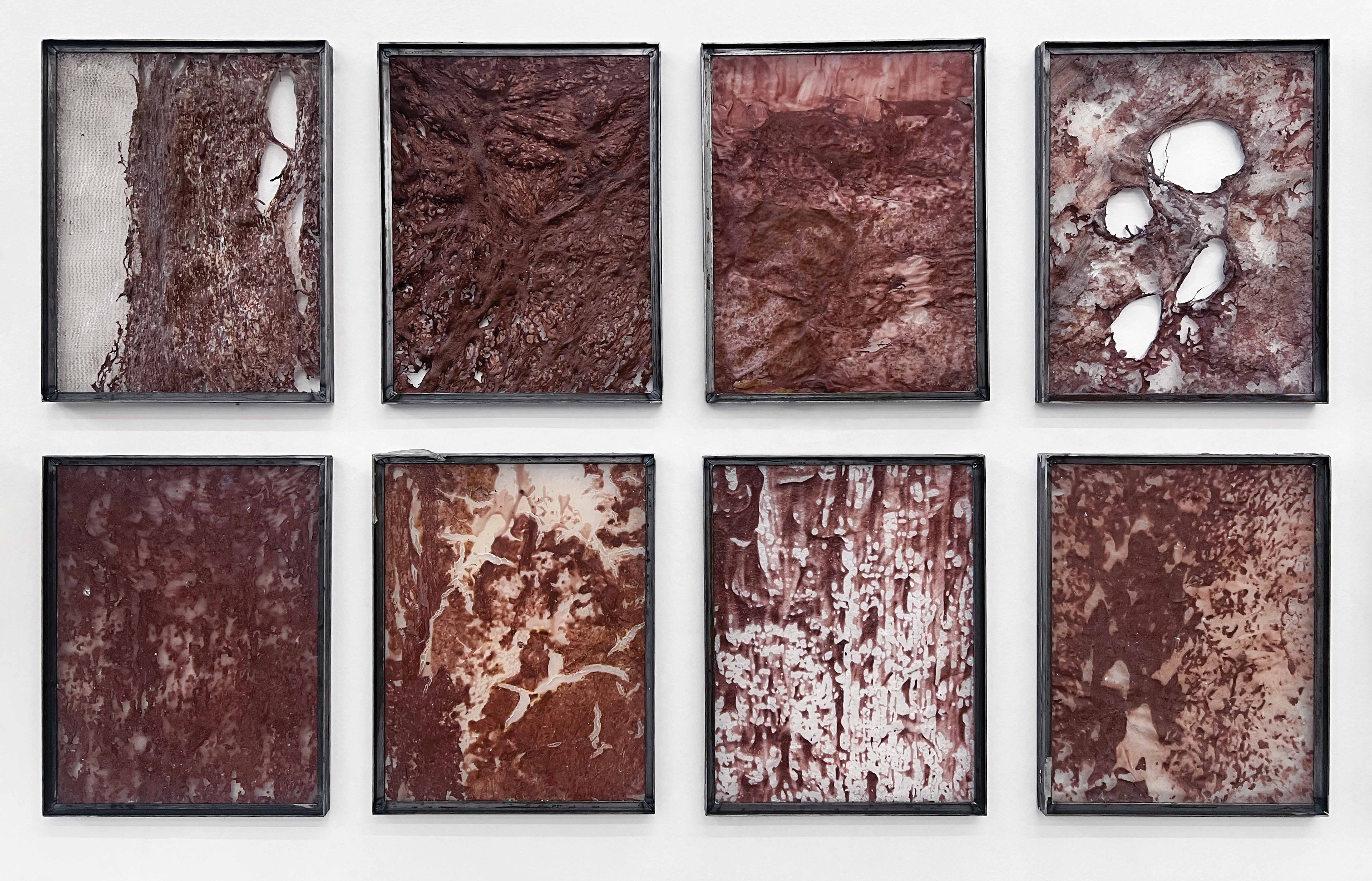

These video works, and some new concrete forms, buttress the feature works within Faces—a series of abraded plasticky skins on metal surfaces, salvaged from parts of previous installations, such as Carriers (2021-22), from the Art Sonje Center in Seoul and Tina Kim Gallery in New York, and leftover skins and a broken turbine prototype from Open Wound, her recent large-scale sculptural installation at the Tate Modern, London. This reincorporation touches on another existential aspect of Lee’s work: the entropic nature of everything, animate or inanimate, and the way care of her material creations can mirror the body and model its care (or neglect).

“So yeah, everything’s material, and they start disintegrating,” she says. “The temperature and the condition to keep them intact is also very narrow. I think because I’m touching them all the time, I’m often thinking about this all together. And then I think about how everything is actually intact for such a short time.”

She pauses.

“If you think about it, we are only briefly intact.”

Mire Lee's show, Faces, is on view at Sprüth Magers in Los Angeles from September 10–October 25, 2025.