F L A U N T

The ancient Greek poet Sappho was the first to call eros “bittersweet,” naming the paradox at the heart of longing. You cannot want what you already have; desire requires a gap, a lack. Centuries later, Anne Carson described eros as the charged interval between reach and grasp. “To be running breathlessly,” she writes, “but not yet arrived, is itself delightful, a suspended moment of living hope.”

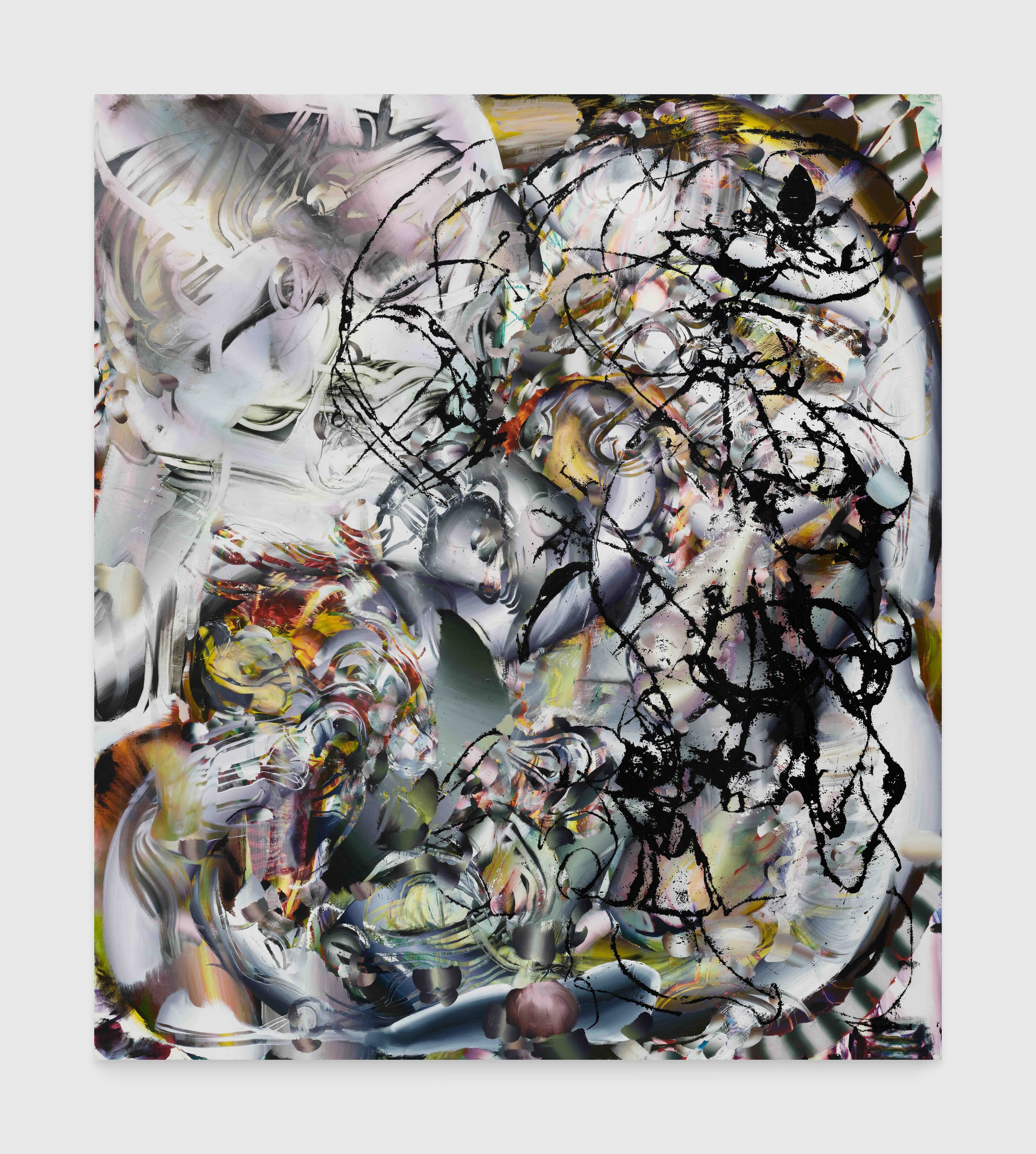

Lauren Quin is familiar with suspended states. The Los Angeles-based painter works at the edge of coherence and dissolution, composing images that flicker just beyond legibility. Her practice, and the paintings it yields, are, in part, structured around the mechanics of desire: its tensions, dynamism, and endless distances.

Quin’s sprawling Culver City studio occupies an actual liminal space between indoors and out. Once a tropical plant nursery, the open floor plan and scattered skylights fill the rooms with diffused light. Verdant palms and fig trees crowd the yard; chromatic splatters of paint stipple the concrete courtyard. When I arrive on a crisp December afternoon, Quin prefaces our conversation with an apology for being “scatterbrained,” though her thinking proves anything but. She is casual but precise, holding and unfolding complex ideas, moving fluidly between registers—music, language, psychology, the body.

The monumental abstractions propped on paint buckets and leaning against the walls demonstrate a similar tolerance for contradiction. One painting in particular draws me in immediately: rendered in lilac, creamy white, and ash-gray, it appears nearly monochrome amid torrents of Pompeii red, lemon, dioxazine, and radioactive orange. Here, sumptuous volumetric tubes intersect with tarry skeins of litho ink, while undulating gradients are interrupted by carved reticular nets. Pigments packed to a velvety density abut washes of limpid color. The limited palette throws the grace and gravity of each gesture into stark relief. Illusory patterns trouble the eye; forms coalesce and dissolve in inexhaustible configurations. Opposing logics—harmony and dissonance, density and openness—are held in active relation. Caught in its thrall, I’m reminded that light is always already a particle and a wave.

The painting belongs to a new series for Quin’s forthcoming exhibition, Eyelets of Alkaline, which will show at Pace Los Angeles in February. Monochrome is her latest “rule,” her term for the self-imposed constraints that structure her practice. Much like poets use meter and verse, she applies boundaries to generate tension, a tension that, in turn, gives rise to invention. “They’re a little like trellises for the work to grow around,” she says.

The monochrome rule was borne of dual desires to quiet the mounting roar of the outside world and to test the internal logic of her images. Would the compositions still hold if their technicolor exuberance were stripped away? “I wanted to prove to myself that the characteristics of my paintings couldn’t be any other way,” she tells me. The monochrome palette affirmed exactly that. Under pressure, Quin conceived of new rhythms, surface impressions, and emotional resonances that imbued the works with a sense of inevitability. In the frame before me, a whole that exceeds the sum of its many parts.

Quin established her first rule during graduate school. While studying at Yale, following a residency at Skowhegan and undergraduate studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, she encountered a painting by French Cubist Fernand Léger which featured a particularly interesting shape—a mark that would become foundational to her practice: a volumetric stroke that held consistent value and weight. “I needed an organizing structure,” she recalls. “This tube completely broke my work open, gave me a whole new set of questions: where is the tube going? Are we inside it? Is it a nerve, a channel, a vein?” Rather than resolving those questions, Quin worked within them. She soon developed her own technique, mixing three or four colors into a viscous goop, then dragging the brush across the canvas, sometimes wiggling it to create undulating waves. The result is a silky swath of luminous color reminiscent of long-exposure photographs of rushing water.

The tube became a kind of scaffolding, what Quin calls a “musculature” or “bone structure” capable of holding dichotomy in equipoise and motion in flux. With each repetition, the mark evolved: the recurring forms alternately resembling arteries, synapses, electrical wiring—each echoing what came before, hinting toward something new. Similar to music, Quin’s paintings are composed of repetition with difference. “You can never fully copy yourself,” she says. “It always becomes the cousin of the idea, something that goes off elsewhere.” Still, the promise of recreating previous forms and the thrill they once induced continue to propel her toward what is just beyond reach.

Quin’s process unfolds in three movements. First, she invents a “problem to solve,” an initial image that’s objectionable or that undermines one of her rules. “If I start with something that’s a mistake,” she says, “then I already have something to contend with.” This initial violation establishes the distance necessary for desire to take hold. Next, she adds successive layers of tubes, shapes, and symbols, then carves into them with whatever tools are at hand—a butter knife, a boba straw, a pointed spoon, her thumbnail—revealing the colors and patterns concealed beneath. “I remove as much as I add,” she says, each gesture renegotiating the last. Finally, she lowers the canvas face down onto an ink-covered plate and draws on the verso, creating a blind-trace monoprint. “I don’t always find what I expect,” she says. “I find something new instead.”

These elusive images recall the hypnagogic hallucinations that the artist has long experienced: rapid three-to-four second flashes of color, texture, and shape that often appear when she closes her eyes. “They’re of nothing namable,” Quin explains, “but they’re incredibly specific. Kind of magic.” She describes trying and failing to catch them, to keep them long enough to draw. “They’re too fast. They just keep going,” she says, adding that they can neither be recalled nor shared afterward. That thwarted closeness, the nearness of something that vanishes as the moment of approach, mirrors the longing turning beneath the surface of her work.

Counterbalancing the rigor of her rules and formal precision is a deeply somatic intuition, honed over a lifetime of making marks on flat surfaces. Quin, who grew up in Atlanta, has been drawing since childhood. Her father, self-taught and technically gifted, remains her most seminal influence. “We would paint together in the basement,” she tells me. “He could paint anything.” Despite years of art school training, she still credits him with teaching her to hold a brush. After she graduated and moved to Los Angeles, he worked as her assistant in the studio for several years. “It was beautiful,” she says. “He’s still one of the deciding voices here.”

Then, there is the scale. Quin is tall, but her paintings are taller: some rise over nine feet high, others stretch up to 15 feet wide. Covering their surfaces in layers of oil, glue, and litho ink requires her entire body. Both an artistic and an athletic act, she reaches her arms up and over, then sweeps them down, miming for me the contours of certain gestures. The varied drying times of her materials heighten the physical intensity: the rabbit-skin glue must stay soft enough to smear, the wet paint must be scored before it settles. The pace and pressure of her brush are preserved across the surface, registering time as much as movement.

Working on multiple canvases at once, she “dances” between them according to her mood and the demands of the next mark. “A gestural move has to be practiced and swift,” she says. “That requires stillness and calm. If you’re nervous or stuck, you have to move to another painting, use it as a repository for the franticness.” Her criterion for finishing a painting is similarly embodied. “When my eye movements slow, it’s done,” she explains. “They’re always racing across it, but when I step back, and they stop or get stuck, I know.” Her feet stop too, “like they’re stuck in mud, and I can’t go any closer.”

Quin’s paintings, however, are never truly finished. Each canvas contains the key to the next: sometimes in particular details, and other times in the drawings along the back. Exhibition titles, she says, belong less to the show at hand than to the one that follows. “It’s really about the future,” she explains. “It’s something to paint toward.” This forward-leaning posture frames each work as a threshold rather than an arrival, and her upcoming show as more of a practice, in the truest sense of the word, than a presentation. “It’s like I’m never satisfied,” she says, laughing a little.

By the time our conversation ends, the afternoon light has shifted from the silver-white of dry champagne to the glowing thickness of marmalade. Soon, all the color and warmth will drain away, and darkness will fall fast and final. As I take a final glance around the studio, it’s easy to see how the mercurial quality of Los Angeles’s light, its extremes of translucency, texture, hue, density, might compel a painter toward the evanescent, the unattainable, the perpetually just out of reach.

In Quin’s phantasmagoric works, all florid and fluorescent, are the undeniable splendors of a Southern California sunset. But in the slippery silver and lavender composition, there is a more nuanced attention to the innumerable shifts that color the city from minute to minute. This commitment to what is always in the process of becoming gives her work its gravity. Even now, it’s hard to turn away.