F L A U N T

Lee Moriarty remembers the exact moment he fell in love with professional wrestling. He was channel surfing as a teenager. His father—a kung-fu aficionado—had introduced him to the films of Bruce Lee, instilling in him an appreciation for martial arts. He immediately recognized wrestling as a powerful form of self-expression, one that merged his fascination with combat and performance with his interest in art—Moriarty drew and at some stage wanted to be a cartoonist.

His debut solo exhibition, Balance, which showed at LA’s Night Gallery last fall, is an amalgamation of his two passions, art and wrestling, and reflects his own professional path, which began in high school. He found a wrestling school near his home in Pittsburgh and enrolled, where he would compete in his first match in December of 2015. From then on he slowly started making a name for himself in the independent wrestling scene, developing a style entirely his own: one that combined Japanese, American, European, and Mexican forms of wrestling.

Known as TAIGASTYLE, Moriarty’s persona in the ring reflects these hybrid influences, as well as his love of hip-hop, streetwear culture, and kung-fu. The colors black and yellow are a recurring motif, a reference to his hometown of Pittsburgh and Bruce Lee’s ensemble in Game of Death. His moniker comes from the opening to the Wu- Tang Clan song “Wu Tang-Clan Ain’t Nuthing ta F’Wit,” the all-caps spelling an homage to MF DOOM.

In 2021, Moriarty signed with All Elite Wrestling (AEW), a move that expanded his platform exponentially. Going pro offered Moriarty the opportunity to return to his art practice, as he found that more stability in his wrestling schedule gave him the time he needed to experiment. “I painted in high school [but] didn’t really like it,” he admits. “I wanted to be in control as much as possible. In drawing or graphic design, you can backspace or erase. With painting, you have a little bit less control, especially when you’re starting out.”

What started off as a hobby quickly snowballed into a new career as an artist. In 2024, curator and independent wrestling promoter Adam Abdalla reached out and asked if Moriarty wanted to exhibit his work at NADA Miami through his publication Orange Crush. Moriarty showed eight paintings, which eventually sold out. The Pérez Art Museum Miami acquired one of them, making Moriarty the first active professional wrestler to have a work in a major museum’s permanent collection.

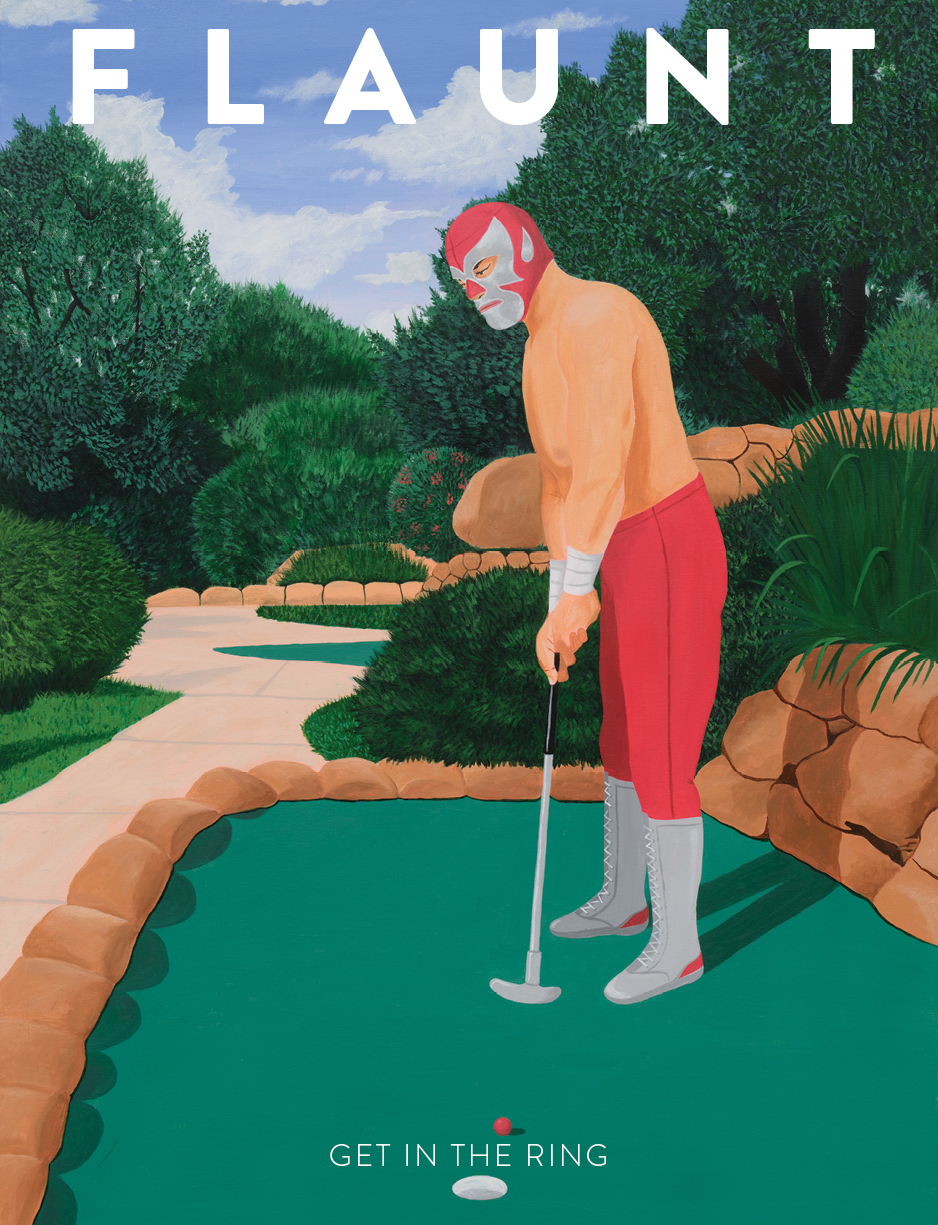

The show attracted the attention of Night Gallery, who approached Moriarty with the idea of a solo exhibition. Since he’d sold every painting he’d ever made, Moriarty had to create a new set of works for the show. “I travel a lot, so I had to figure out a game plan. I set the goal of one painting a month.” Fittingly titled Balance, the exhibition features eight paintings that offer a more nuanced perspective on luchadores, practitioners of lucha libre, a Mexican style of wrestling that incorporates masks and elaborate acrobatic maneuvers. His portraits draw inspiration from lucha libre icons El Santo and Blue Demon and luchador films like Santo y Blue Demon Contra Los Monstruos.

Instead of depicting luchadors inside the ring, Moriarty captures them in unexpected moments of quietude; one luchador birdwatches on the beach, another carefully assembles a snowman. A deft painter with an astute eye for color, Moriarty’s paintings are playful and whimsical while retaining a sense of groundedness. His use of flattened perspective and saturated hues recalls Alex Katz and David Hockney.

Moriarty cites Tyler, the Creator as a key influence for his use of “softer aesthetics”—warm colors and pastels— within a genre typically seen as “more aggressive.” One can see this influence in “Pink Mink Portrait” (2025), which references rapper Cam’ron’s iconic bubblegum pink mink coat. Flanked by lush cherry blossom trees, the luchador in the portrait peers off enigmatically into the distance. Both the trees and texture of the luchador’s coat, rendered in great detail, convey a sense of movement and flow.

Moriarty is a practitioner of llave, a subset of lucha libre. “It’s the same as in American wrestling,” elaborates Moriarty. “We have the brawlers, the high-flyers, the technical wrestlers. Technical wrestling and llave are similar. Llave [involves] tying people up in unique knots and submissions and flowing through things. The reason I appreciate llave style is because [of] the way they make things so smooth and flow into everything they do. It’s a lot of mental work to remember all these holds that transition from hold A to D.” In June, Moriarty went to Mexico with AEW and Ring of Honor, where he trained with llaveo master Negro Navarro.

Professional wrestling is often disparaged as “low- brow” and a lesser form of entertainment. Yet it is incredibly complex. As a spectacle that melds choreography with improvisation, it’s more akin to theater and dance than sport. Each wrestler has a particular role, and in the ring, they work together to tell a story through the body. In American wrestling, matches often function like morality plays in which wrestlers embody the struggle between “good” and “evil.” Although the result of each match is pre-determined, wrestling’s physical demands and live nature add an element of real danger. A wrong move can not only ruin the story, but also be fatal.

For Moriarty, professional wrestling and painting are not opposites but rather part of a fluid creative practice. He designs his own merch and made a zine just to learn how to do it. “I’m very open to doing whatever comes my way,” says Moriarty. “I have these goals, and if I meet them, great. If I don’t, who knows what I can accomplish in between reaching them. Japanese wrestling is something I appreciate. A big goal in pro-wrestling is to wrestle in Japan. With art, my goal was to have exhibitions, and now I’ve [had] my first solo one in LA.”

A fan of KAWS, Nigo, Human Made, Moriarty would like to get more into streetwear and product design. “AEW every once in a while will release a special shoe with Champ Sports. If I can design a shoe, that’d be pretty cool. Collaborative projects are really fun because it’s not just me making art by myself. It’s me working with someone to create something new.”

Whether he’s in the ring or in the studio, he’s world-building. “That’s my goal, to expand what my art can be outside of just a canvas, or me wrestling on a canvas.”