F L A U N T

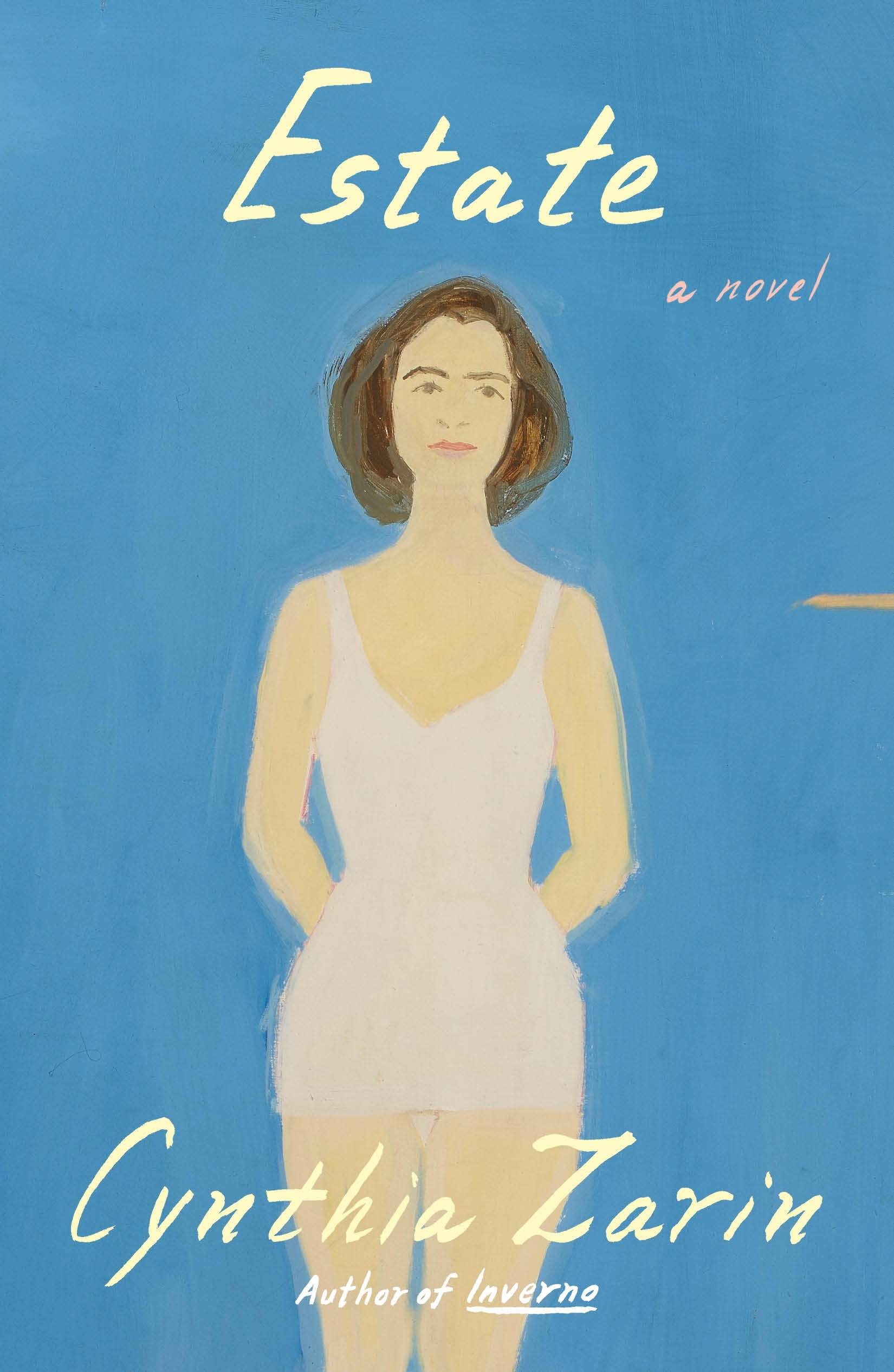

Love, in its essence, is messy. Love burns, love stings, love pierces through the skin—and yet we can’t seem to ever get enough. To revel in its disarray is to buy into our species’ most revered story: that people can grow an affinity for one another beyond an amiable affection or alliance. Estate, the latest novel by award-winning poet and journalist Cynthia Zarin, lives in this mess.

The book is a stream-of-consciousness tale told through the eyes of Caroline, a woman who, after separating from her husband, has found herself entangled in a relationship with Lorenzo, a man in relationships with multiple women. Over the course of the novel, Caroline tells stories to Lorenzo—fictional fables, recounts of their times together, and musings on whether or not she should leave him. At times, her narration feels like a spell she casts over herself as much as over him, an attempt to understand desire by speaking it into being. What results is a beautiful meditation on love and agency, told through the private cadences of a mind trying to steady itself amid emotional drift.

Caroline is a character Zarin has known for quite some time now. She first appeared in Zarin’s first novel, the third-person Inverno (Italian for “winter,” coinciding with Estate's Italian summer), now taking full force in the first-person. “Starting with the little scraps of Caroline’s voice came her saying, ‘Now it's time. Now it's time for me to speak,'” Zarin tells me. That insistence, she adds, was inevitable, as though Caroline had been clearing her throat for years offstage.

Estate begins as a letter from Caroline to Lorenzo, detailing her life and thoughts when they are not together. This long letter, as told from Caroline to her lover, began as a letter Zarin herself crafted, longer than she ever anticipated writing. She describes the experience almost as a fever—one of those sudden writing spells that take root before you realize they’re becoming a book. “I had never been the kind of person who sits around saying, ‘Oh, I'm going to write the great American novel,’” Zarin says, joking that Estate might fit as a great French novel, due to its slim profile. “I had begun writing this long letter, which then became this huge, massive prose over many, many years, and I had no idea what to do with it. And through a series of happy and unhappy accidents—first unhappy and then happy—because I kept trying to do something with it, some of it became Inverno. What had started out as a letter became kind of experiments and stories, making things up, recording things, recording everyday life, making things up about ordinary life, all the kinds of things that one does. When I finished Inverno, I had a lot left.” And thus, Estate, and the unconventional love story of Caroline and Lorenzo, was brought into the ether.

Discussion of love and relationships today is as bountiful as it is fraught. Monogamy goes in and out of style every few years, with each generation believing that they themselves have made the groundbreaking discovery of sleeping around. It’s a cultural pendulum swing that both mirrors and obscures the private, unglamorous work of navigating intimacy. “We live now, oddly, in an extremely rigid and puritanical time,” Zarin remarks. “Even if people do things like throuples and things like that, there still seem to be a lot of rules around them.” Estate is certainly not your conventional marriage plot. “She's in love with him. He breaks her heart over and over again, and then she renounces him and realizes that he's a terrible person and she should never speak to him again,” she tells me. “Or maybe she does decide that in some ways, he's a terrible person, but it doesn't occur to her to never see him again, and their life just goes on.”

She goes on to recite a quote from Penelope Fitzgerald’s 1986 novel Innocence that goes, “‘We can't go on like this.’ ‘Yes, we can go on like this,’ said Cesare. ‘We can go on exactly like this for the rest of our lives.’” While Caroline struggles with her vestigial attachments to conventionality in the face of her rather bohemian relationship, she searches for something else entirely. In her exercise in agency and desire to explore the unknown, Caroline is at the helm of her own story. “Caroline would always go for the secret third thing,” Zarin shares, referencing a meme format I brought up earlier in our talk. It’s a joke, yes, but also the closest thing to a thesis Estate offers—a recognition that life rarely presents us with simple binaries. Caroline isn’t choosing between Lorenzo or solitude, fidelity or chaos, tradition or transgression. She is choosing the option that resists naming, the one that asks her to step into the dark and see what shape emerges. In that sense, Estate is not a repudiation of conventional narratives so much as a gentle dismantling of them, revealing the seams we pretend are not there.

Zarin herself is an artist whose work and career defy categorization. A “poet first, journalist second,” as she tells me, her work relies on the internal and external reporting and uncovering of the most intimate truths of the systems and individual worlds that exist in our society. You may recognize her work from the New Yorker, where she’s spent several decades as a staff writer and contributor, or maybe you wandered into Manhattan’s Cathedral of St. John the Divine during her time as poet-in-residence. Perhaps you grew up reading her children’s tales of dogs who ride taxis and boys who grow down instead of up. Read enough of her work, and you start to sense it: the unmistakable signature of a writer who sees the world in layers.

What becomes clear in talking with Zarin is that her writing—across genre, across form—springs from the same root system: a fascination with the intricacies of human attachment, the invisible threads that bind and unbind us. Estate may be a novel, but its engine is lyric, its heartbeat unmistakably that of a poet.

“Not all kinds of love have to be a certain way,” Zarin tells me. “Love is elastic.”