F L A U N T

It is important to keep in mind that, by definition, the utopian dream cannot be realized. Thomas More’s island, Campanella’s commonwealth, Fourier’s passionate society all asked: what perceived personal liberties could one forgo, on an individual level, to achieve collective social synergy? And all in their own way underscored the futility of that ambition, the tragedies of the real world within the social contract. Though these placeless ideals are exercises in critique, our pursuit of a built utopia has not ceased. In America, the utopian pursuit abounds; billion-dollar industries are constructed on the illusion of an Earthly kingdom without personal sacrifice, all promising that we can, one day, have it all—total access to one another, to goods and services and to companionship. Are we laboring under delusion? Does our exceedingly bountiful yield not come at a cost?

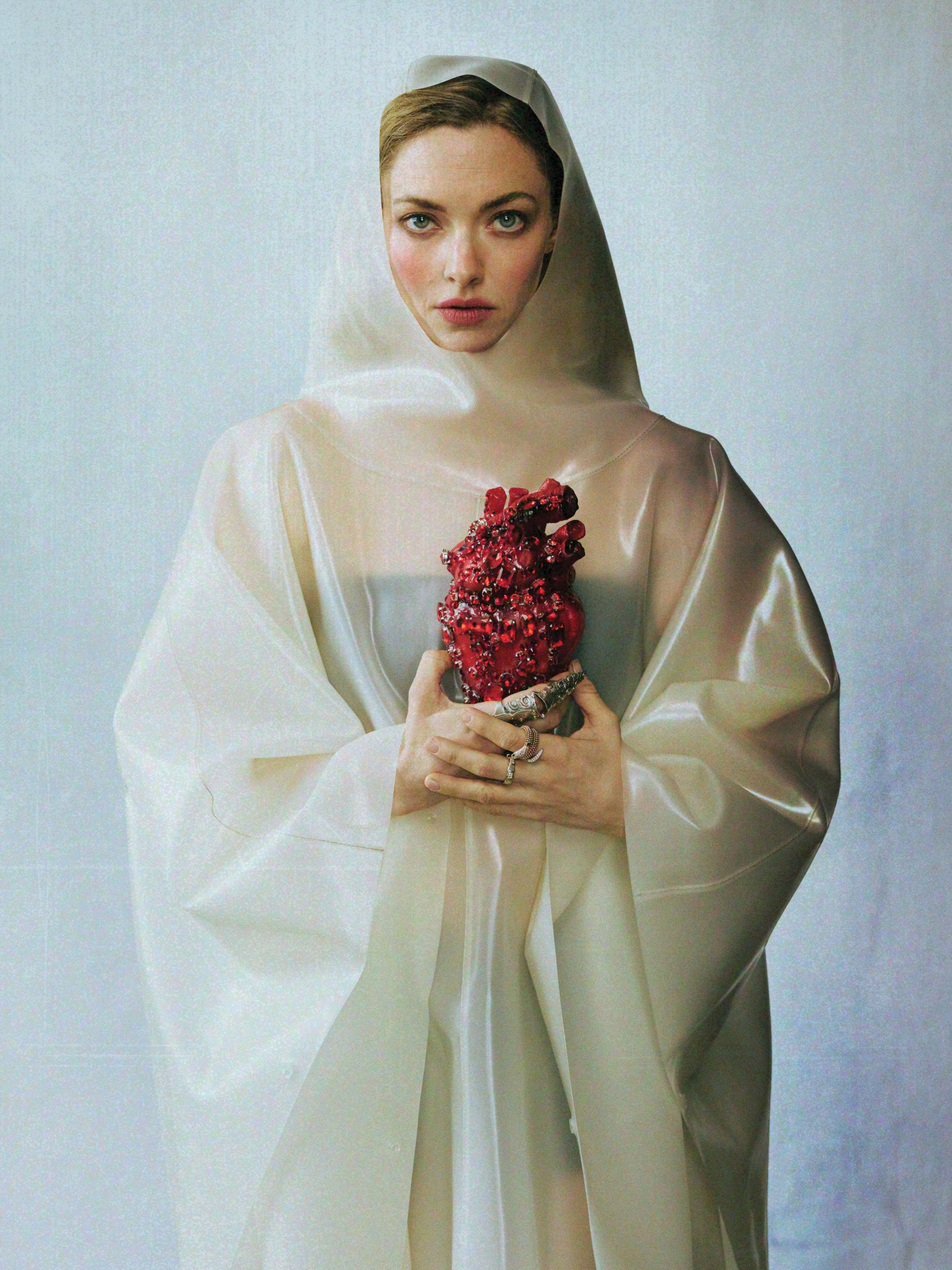

In our conversation this morning from Palm Springs, Amanda Seyfried is trying to make something of the conflict between hegemonic power and individual sovereignty. Seyfried, a longtime participant in and face of the industrial fantasy complex, or utopia, that is Hollywood, has determined that modernity comes at the cost of deliberate, willful, personal choice.

“We’re losing power all the time,” she asserts. “Like, all the time. We’re losing privacy, and we’re losing our autonomy. So many sacrifices that we’re making [today] are made unconsciously…but I think we still have the power to make waves for ourselves and for each other. We still do.”

It is strangely reassuring to listen to one of the most well-loved tenants of the industry speak with equal parts distaste for the present and hope for some meaningful future. After all, Amanda Seyfried is a generational talent, someone who wields the soft power to command the attention of several nations—from her breakout role in high school satire Mean Girls to her contagiously joyful presence in beloved Grecian epic franchise Mamma Mia!, to her pure-of-heart embodiment of Cosette in Les Misérables; her meek turn in Jennifer’s Body or her uncanny and cunning portrayal of Elizabeth Holmes in The Dropout, or even her recent appearance as scorned wife Nina Winchester in mystery thriller The Housemaid: these roles have located Pennsylvania-born Seyfried, with her recognizable shock of blonde hair and wide green eyes, as someone with say in an entertainment-centric America, and, demonstrably, a firm believer in the correct way to communicate it.

Recently, Seyfried has been made to think about the strength of individual affect through the lens of 18th-century religious leader Ann Lee, whom she vivifies in Mona Fastvold’s moving, historical musical The Testament of Ann Lee. In the film, Fastvold (The Brutalist, Vox Lux) braids generations of tales—factual records, oral traditions, hymns, myths—about the female founder of the American Shaker movement into a tapestry that ripples with devotion, ecstasy, grief. The Testament of Ann Lee—realized alongside co-writer Brady Corbet (Thirteen, Mysterious Skin, The Brutalist), choreographer Celia Rowlson-Hall (Vox Lux, Aftersun), and composer Daniel Blumberg (The World to Come, The Brutalist, Below the Clouds)—is as much an attentive account of Ann Lee’s life as it is an endeavor to grapple with truth and belief as one, and an exploration of what it means to use one’s body as a means for that equivocation.

And Ann Lee, the real woman, the leader, the Shaker’s female Second Coming of Christ, did devote her life to both. The film follows Seyfried as Lee, utilizing movement and melody to detail a lifelong, continent-spanning epic. There’s Lee’s childhood spent in Manchester under the austere rule of the Church of England, a discovery of local Quaker meetings, (throughout which the camera follows Seyfried as she and the ensemble move as one, thrusting fists from chest to sky). There are songs of agony as Lee endures marriage to Abraham Standerin (Christopher Abbott) that yields four dead children under the age of one. Then a longing, lonesome melody “Hunger and Thirst,” as Lee endures a hunger strike during religious incarceration that catalyzes visions of God. In the scene, Lee levitates off the ground, and the camera stays right next to her in that pale light, catching her ragged breath, as if inviting the watcher to reach through the screen and caress the downy fur sprouting on her forearms.

Ann Lee’s visions, her connection to God, are not ridiculed by Fastvold—they’re taken as visceral truth. It is possible, the telling of this story for an increasingly Godless, logic-based 21st century, for Ann Lee to be grieving, starving, delusional, while also utterly holy. Whether she is or is not the Second Coming of God is not the question splayed out so carefully in the moment. Rather, it asks if Lee—and, by proxy, her viewers—is willing to accept the call to God. Her acceptance is unwavering.

So, too, is Lee’s direct path to salvation. Salvation, then, means total abstinence, a refusal to engage in any carnal sin. From whence, Mother Ann, under a dictate from the Lord alongside her brother William (Lewis Pullman) leads a sparse crew of believers away from persecution in Manchester to America at the turn of the American Revolution, dancing and singing under direct sunlight to celebrate the miracle of God’s blessing on a voyage across the Atlantic, finally settling in the wilderness of Niskayuna outside of modern-day Albany. The purity of their belief is steadfast. On route, they attract believers to this strange isolated field to engage in the righteousness of woman-as-leader, founding a settlement that would spawn others across the eastern seaboard, allowing female leaders and welcoming Black community members, (eventually, the Shakers would play a role in the liberation of enslaved peoples). The sacrifice, for these small forward-thinking communities, was sex. Where the flesh begot sin, song, dance, community begot forgiveness.

When Seyfried speaks of Ann Lee (for which she will win Desert Palm Achievement Award at The Palm Springs International Film Awards in the hours following our conversation), her vocabulary dips just-so into an ecclesiastical sort of humility, mimetic of the tone of the film itself. “[When I signed on] I just had to become an arm [for Fastvold’s vision]. The center was there. I just got to fly in and attach myself to it,” she says, taking extra care to underscore the miracles of the team as a whole, the communal experience subsuming the individual. “In that way, a lot of the work had been done for me, and I could really hone in on what it was that [Fastvold] needed from me that no one else could offer. I needed to be that vessel,” she concludes.

It is metaphorical turns of phrase like this: “the vessel,” “the core,” “the vision,” that so easily allow one to imagine the cast, the audience, devoting a portion of their lives to Ann Lee, at least for a moment, with as much care as she devoted to her religion. We are there, right with the hundreds of bodies squirming together in the heat of the summer in the midst of geopolitical and philosophical unrest, just as the Shakers worshipped. In isolation, in total and uninhibited ecstasy, knowing each other’s bodies and speaking in the language of their own design, their devotion to their Lord or their story ringing, cacophonous, exhausting.

Is it, though, such an enormously difficult thing to consider dance and song as means of connection to God, in place of sex? “It’s an energetic and physiological kind of experience that kind of puts you in a place to be able to have an opening of the heart,” Seyfried asserts before laughing: “Oh, what the fuck am I talking about? I mean, I like, why do people go to raves? Why do people go to the club? [To dance together] is a shared experience that can take you over, connecting you to yourself. More than anything, [dance] connects you to something greater.”

It is of note, though, that while Ann Lee has been justifiably hailed as Seyfried’s most vulnerable picture yet, it is just one of Seyfried’s long list of projects that showcase her mastery of music and dance as a means to deliver joy, peril, pain. Seyfried has formidable gift for empathetic performance, but her acumen for movement and song is nonpareil—an audience can listen to her clear soprano “In My Life/A Heart Full of Love” in Les Misérables and see, so clearly, her neatly braided hair tucked in front of her shoulder, her gaze cast through a cast iron gate in 19th century France.

This extends beyond the frame. Mothers and daughters across the world have developed rituals around the viewing of Seyfried as she twitters about a Grecian villa alongside Meryl Streep and Colin Firth in Mamma Mia!, as if they, too, are drunk on wine on a beach on the verge of the 2008 financial crisis. Even Seyfried’s scene as Elizabeth Holmes, awkwardly moving gangly white limbs to Lil Wayne’s “How To Love” in front of her partner and lover Sunny Balwani is one of the most widely beloved scenes of The Dropout. In the past, Seyfried has been open about a lack of personal religiosity, but it is difficult to believe a mastery of the disparate arts, the ability to direct attention and ignite imagination and love within a group of witnesses without stratifying salvation based on class or belief, is so different than piety.

“That’s the thing about faith,” says Seyfried, “[Ann Lee] is less about who your God is, and more about who your community is. It’s a great way to look at religion. And because religion is powerful. I mean, look at the world…the rules in so many religions are in place to protect not the congregation but the leader. We need to continue to look at that because there are such blatant, impractical things being put into law that are so clearly in protection of the leader and not the people.”

Seyfried thinks often about the protection of The People, as it were, particularly in relation to modern forms of storytelling. In the two films she’s been (very, very busy) promoting this season, both Ann Lee and The Housemaid, the actor has been made to consider the generative role of the female in power in blockbuster entertainment. I point out that, if there are any parallels between these narratives, it is the assumption of dominance, whether by way of total abstinence or—in the case of Nina Winchester from The Housemaid—violence; cunning.

Why do audiences clamor for these types of reclamations, particularly by female protagonists? “I mean we all need some distraction, for sure,” Seyfried grins. “But if you look at animated films for kids, [the message] is always about people finding their inner strength. I hate to sound so cheesy, but it is about finding your voice, finding your strength, and re-creating your space in the world, like owning your space in the world.”

Seyfried’s space in the world is, at present, a farm in upstate New York, which she shares with her husband Thomas and two children. In December, she inaugurated her 40th year, which she’s “inviting in, softly.”

“Listen, I live on a farm for many reasons, but one of the reasons is that I just don’t want all the noise,” she states. “I want to be able to choose what my day looks like and who I see, and what I’m surrounded by. That’s the way I control what comes in.”

Amanda Seyfried desires autonomy. It’s an intention reflected in the sentiments of so many in the public sphere—particularly working women, particularly working mothers. If the world is a place of chaos; perhaps it is because our structures of power work overtime to conceal pain. Maybe, then, the promise of a modern utopia should not be predicated on personal convenience, but rather, on choice. Seyfried likes to choose her sacrifices, and she begins by asking what she owes herself, which will in turn allow her to find clarity on the things she feels she owes the world. “When I’m really paying attention and considering myself, that’s only liberating, but incredibly impactful.”

Photographed by Greg Swales

Styled by Christopher Campbell

Written by Annie Bush

Hair: Orlando Pita at Home Agency

Makeup: Genevieve Herr at Sally Harlor

Nails: Mo Qin at The Wall Group

DP: Chevy Tyler

DigiTech: Sara Lewis

Production: Alexey Galetskiy

Photo Team: Daren Thomas, Tom Rauner, Taylor Schantz

Production Assistant: Alexandra Strasburg

Stylist Assistant: Mia Hurley

Location: Vandervoort Studio