F L A U N T

A few days after the start of her tour promoting her third studio album BLACK STAR, Amaarae is still in awe of the audience she’s built. That performance, a sold-out show at Knockdown Center in Queens, NY, was a testing ground for how she and her crowd would navigate this iteration of her diaspora-spanning sound, encompassing tenets of Afrobeats, Ghanaian highlife, baile funk, hip-hop, and queer-coded electronica, in a live setting. Promo encouraged fans to show up in all black, and many obliged. “If you’re wearing all black and you’re looking up at me on stage wearing all black, you see yourself in me,” she explains over Zoom, dressed for the part in a black durag and matching Von Dutch t-shirt, in between lateral movements on an elliptical machine. “It’s important for my audience to see themselves as stars, to see themselves as people who can make their own dreams come true. So I might be the medium for now, but for me, I think it’s just a projection of what’s to come for their future. I like to spread confidence and love and hope in the world, especially given the times that we’re in.”

She remembers a specific moment from the show when that idea became reality. When it was time for the sultry pulse of BLACK STAR cut “Fineshyt,” she brought a group of audience members onstage to dance with her as the show came to a close, and they jumped at the chance to flaunt their shit. “They damn near kicked me off the stage!” she says, laughing. “Everybody forgot I was there. They’re like, ‘I’m the star now.’ I was like, ‘Okay, period, this is your stage! Cool, got it.’ If you watch the video from that night, it’s less chaotic and overbearing than it sounds. Some fans are off dancing in their own little worlds; others whip out phones to record the moment or raise their arms to hype the crowd. Regardless, Amaarae is the center of gravity they all orbit around, forming a loose horseshoe around the brightest BLACK STAR in the building.

It’s a level of adulation she hasn’t fully gotten used to yet. Though Amaarae, born Ama Serwah Genfi and raised between Atlanta, Georgia and Accra, Ghana, has been releasing music since 2017, 2023’s Fountain Baby was a quantum leap in both her artistic vision and pop cultural appeal. The electro-African vibes she’d been refining on projects like The Angel You Don’t Know and Passionfruit Summers came to the fore with grand productions and lyrics that found several ways to embrace the euphoric highs of new stardom and the steamy intimacy of club bathrooms with equal passion. Baile funk slappers, afrobeats syncopation, and an interpolation of the Clipse’s “Wamp Wamp (What It Do),” soundtracked the dive into the good and evil of a newly affluent celebrity lifestyle, and its versatility sent it into the stratosphere.

“People know that I’m an artist that likes to take chances, that likes to work with fusion, but I don’t think they saw that album coming,” she says. “The element of maybe being underestimated a little, worked in my favor. I remember saying through that whole process of creating the album, ‘I want this to be a worldwide project. I want this to be a global project.’ And, ‘I want to take over the world with this.’ I think that, in some way, shape or form, that manifestation came to life.” Amaarae barely had time to process the movement. Before long, she was on the road touring by herself and, eventually, being an opener on stadium tours for stars among the likes of Sabrina Carpenter. “These were such young, predominantly Caucasian crowds. But I was glad I had the platform to show kids that ordinarily would never come across my name or my music—something new to unlock their imaginations.”

In the process of opening up minds on the road, Amaarae was also figuring out her next steps. She wanted to platform Ghana in a more explicit and intentional way without making something expected, and part of that consideration came from doubts about how her last project would be received by her home country: “I was surprised at how the tide turned for me with Fountain Baby back home, because Fountain Baby—if you’re just looking at local hiplife, highlife, afropop—is forward-thinking. I didn’t expect anybody in my country to fuck with it, let alone like it. So coming off Fountain Baby and going home, people are recognizing me for this very polarizing body of work that they seem to love and respect to the point where it’s raised my profile back home. I’m like, ‘Okay, so this is a nation that’s hungry and thirsty for more, for something that is exciting and different and fresh and new,’ and that is what shifted my mindset to be like, ‘I want to be the Super Hero for my country. I want to be the flag bearer. I want to be the representative for my country. I don’t want it to be anybody else.’"

Ironically, the idea came from a quick scan of the American and European pop landscapes. She looked to albums like Drake’s Honestly, Nevermind, Beyoncé’s Renaissance, and Charli xcx’s BRAT, all of which were steeped in various traditions of dance music, and compared those to the kinds of music coming out of Ghanaian cities like Accra, Kumasi, and Sekondi-Takoradi. “Africans like their drums light, bouncy, and groovy, so what if we make it polarizing? What if we, instead of using a rim shot or a clap, just put a kick where a rim shot or a clap or a snap is supposed to be and change people’s minds about traditional patterns of rhythm?” It’s bold enough that, on the album’s cover, she’s sitting in front of a giant Ghanaian flag, dressed in black skintight leather, standing in for the literal black star at the flag’s center. But that mentality became the nucleus for BLACK STAR, a way for Amaarae to represent her heritage and musical acuity on her own terms.

Sonically, BLACK STAR is darker and more synthetic than Fountain Baby. While both projects are practically writhing with desire and swelling with national pride, BLACK STAR is clearly made for the dancefloor. Sometimes, it’s on the nose, like with the ballroom-ready “ketamine, coke, and molly” hook powering “Starkilla;” other times, the pulsing 808s of songs like “ms60” or “Girlie-Pop!” make it most apparent. The album’s most interesting moments come from Amaarae’s vision of tweaking African sensibilities, which is most visible on penultimate song “100DRUM.” On it, a rhythm sitting somewhere between Afrobeats and highlife is bolstered with heavier drums. It’s airy around the edges, but bludgeoning at its center, and the syncopation is a bit more jagged than what you might expect.

It can’t be overstated just how blinding the critical acclaim was for Fountain Baby: The album scored a 95 on review aggregate site Metacritic; Pitchfork gave it a rating of 8.7 out of 10 and its vaunted Best New Music stamp. While BLACK STAR still fared well—Pitchfork actually gave it an 8.8, a tenth of a point higher than Fountain Baby—Amaarae says that, from the listener’s perspective, the album received “the most mixed reviews I’ve ever gotten.” Plenty of fans love it, but some trusted voices in and out of her circle have been less kind (“My own brother was like ‘I hate this shit, yo. This might be one of your worst.’”) She remembers a specific criticism (from “a critic I really respect who gave Fountain Baby a nine but gave BLACK STAR a five”) that called the music on the album “too simple” and pointed to album closer “FREE THE YOUTH” as a song that “lacked the progressions and excitement” of her earlier work.

“It’s interesting, because there’s a version of ‘FREE THE YOUTH’ that has four different beat changes in the song, which is very similar to something that I would do on Fountain Baby,” she says. “And I remember listening to that version, and listening to the version we have now, and just being like, ‘The simpler version is the way to go,’ you know what I mean? I guess I was surprised, or maybe disappointed, that people would think that the choice to be simple was a lazy or unintentional one, versus an actual meditation on what this should be and why? And to think that the time spent on the last one wasn’t equal to the time spent on this one, just because it’s not dynamic in the way people who love Fountain Baby expect it to be.”

Shortly after breaking that critique down, Amaarae tells me she’s gauging opinions and asks me my honest opinion on BLACK STAR. I tell her even though I think both albums are exceptionally well-made, I found myself gravitating toward Fountain Baby more strictly because of its tone, the sweaty summertime feel the project gives me. It has nothing to do with a purported lack of musicality—BLACK STAR is a vibe I simply hadn’t fully settled into yet; it has some songs I enjoy more than others, but even in the lead-up to this interview, a handful of them had begun to grow on me. “I definitely feel like that’s been the general consensus,” she replies. “I like that it’s an ongoing conversation, versus with Fountain Baby, where everyone was like ‘Oh shit, this is the one.’”

Regardless, Amaarae is proud of how BLACK STAR turned out. She’s more visible now than she’s ever been, and relishes standing firm in her position as both an emissary and role model of Black, queer, and Ghanaian expression.

“It’s my responsibility at all times to make sure that if I make art that is difficult or polarizing to discuss, that I am in full health and of sound mind to add valuable context and conversation to any kind of thoughts, feelings, or public opinion that my art stirs up. I think that it is my responsibility to hold the space as a role model, and when I say role model, I don’t mean being perfect, I mean being human, showing growth, but also realizing that there is a responsibility to uphold a sense of pride and honor as a Black woman for what I do, but also as an African woman for what I do, and there’s so much attached to that. I do this for everybody but for like the little girls really like me, that don’t have a space to see themselves, you know, and the little boys that also don’t have a space to see themselves, and even some of the grown ass people that don’t have a space to see themselves or are in denial, especially being African. So it’s a very important responsibility for me, and I do not take it lightly at all.”

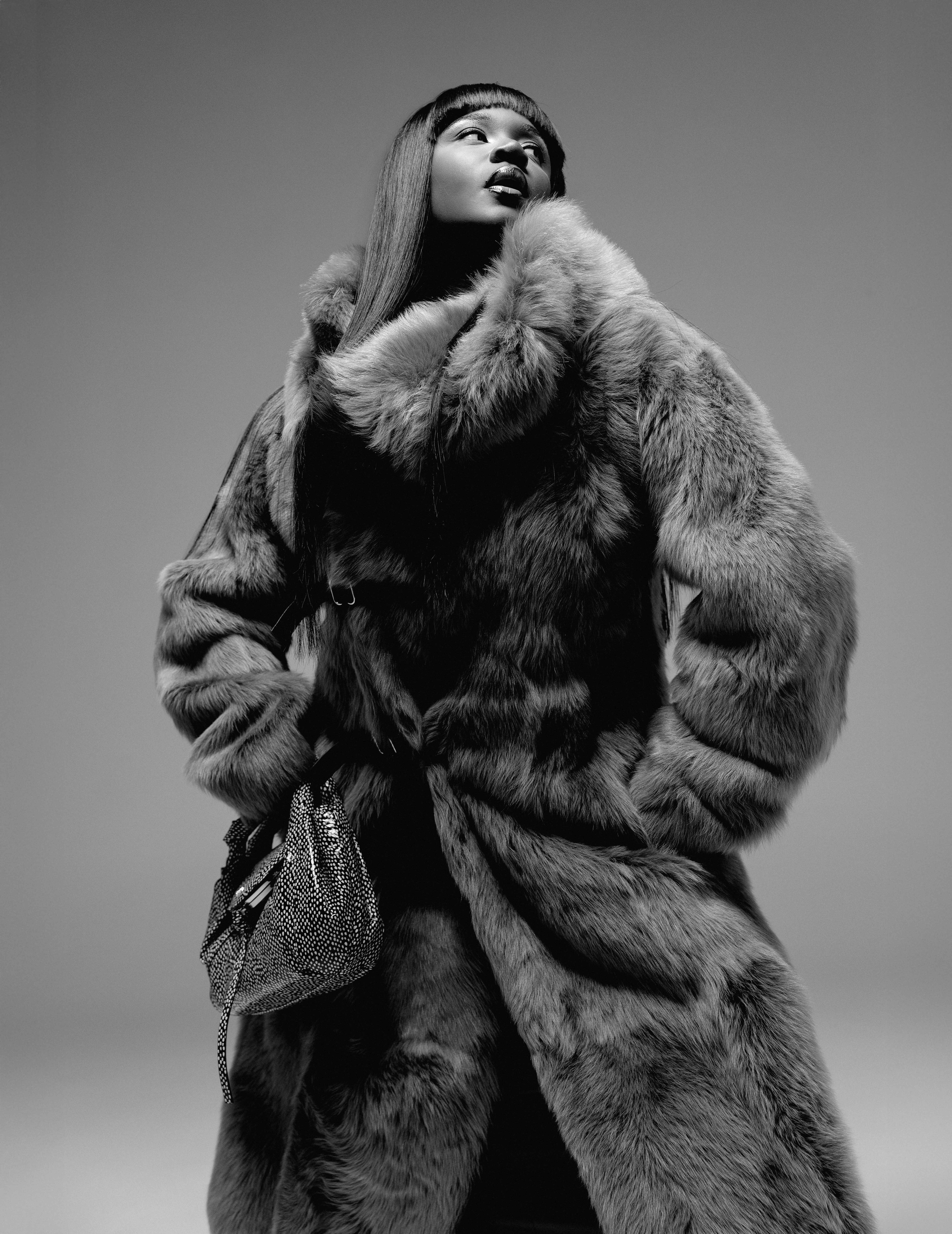

Photographed by Kanya Iwana

Styled by Michy Foster

Written by Dylan Green

Hair: Maykisha Bowers

Makeup: Ashley Elizabeth

Flaunt Film: Simon Gulergun

Style Assistant: Diana Valdovinos

Production Assistant: Ke’von Terry

Location: DFLA Studio