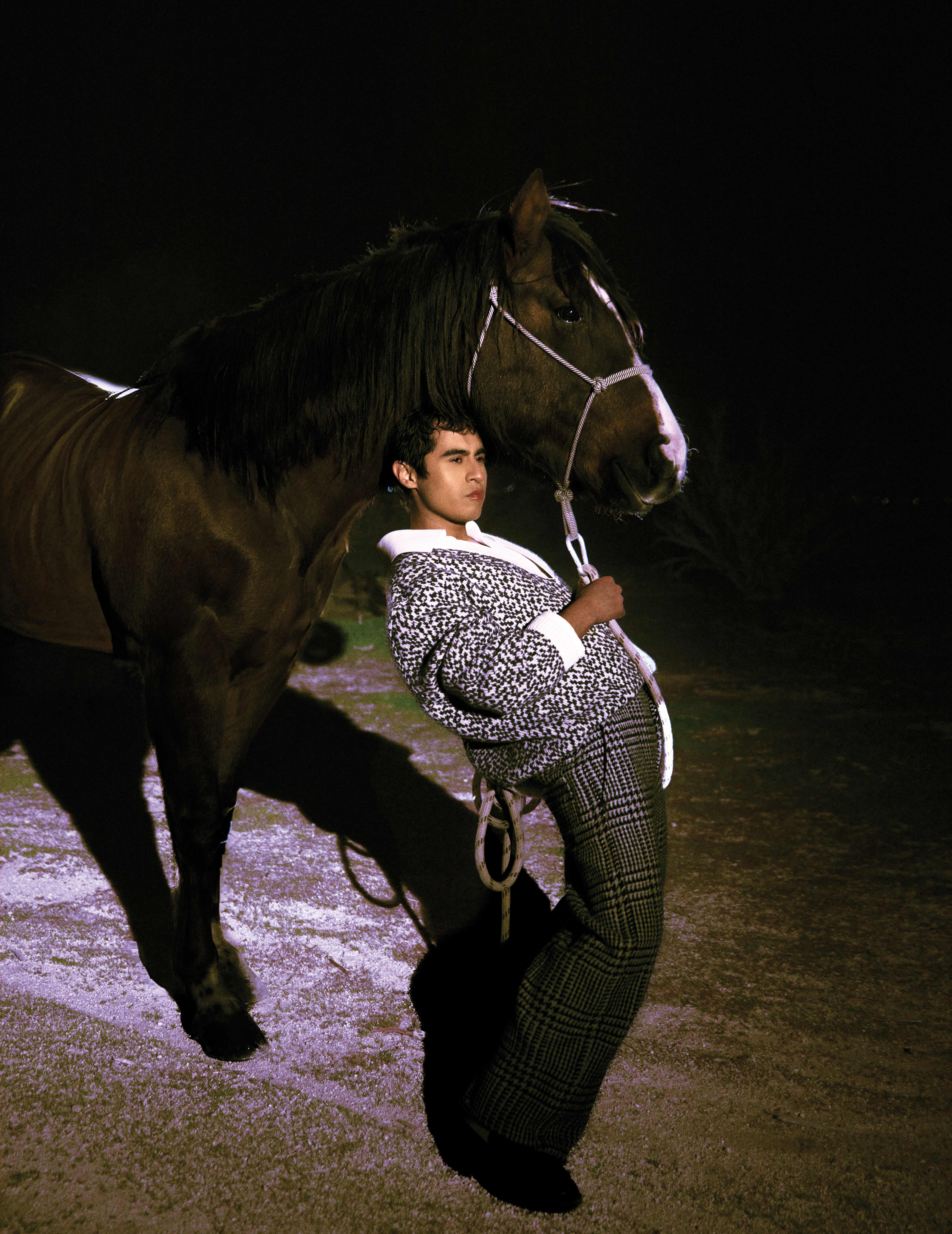

Photography: Chiara Romagnoli at ChiaraRomagnoli.com. Hair and Makeup: Annabel Callum at AnnabelCallum.com.

Scottish composer Anna Meredith’s adopted south London home, Camberwell, is dilapidated, hot to the point of exclamation and cramped with the noise of traffic-clogged roads—the kind of environs imposed by circumstance, rather than chosen. To get out of the heat, we adjourn to a small pub with old oak tables and order pints of lime and soda. Now not so repulsively hot, I realize maybe I’ve been a little too harsh to Camberwell. It boasts a pretty interesting list of people who call it home, like Florence Welch, of Florence + the Machine, playwrights Martin and John Michael McDonagh, and writer Zoe Williams. Maybe it’s close, crowded on the streets, and the cracked leather sofas in the pub look dreadfully uncomfortable, but in the countenance of this pub’s edifice, there’s a note of openness, as though willing to make room for any number of ideas.

“I feel comfy here,” Meredith says. “It’s an honest place.” Openness, like honesty, is integral to a sense of community, and, as she suggests, to good collaborations. “A few years back,” Meredith says, she and her composer friends who live in the area, “\[We\] started the Classical Composers Collective. We’d put on regularish gigs in the crypt of the jazz club down the road, which opened one night a week. Composers are often commissioned to write pieces, so you don’t always get to choose who you work with, or the criteria the piece is built around. Composing can be a very solitary thing, where you’re pacing around your room; the collective was our way of having a bit more control over what we do, and choosing our own collaborators.”

One possible way to proceed with Meredith’s compositions is to see how her command of influence opens up the formal and systematic aspects of classical music to multiple and different subversive elements. In turn, she’s able to relate the multiple to a unity. Her _Concerto for Beatboxer and Orchestra_, for which Meredith collaborated with U.K. beat-boxer, Shlomo, formalized the very improvisatory art of beat-boxing by notating every guttural, and the latest piece, _HandsFree_, which was performed recently at The Royal Albert Hall as part of BBC Proms 2012, furthered the subversive spirit by having an orchestra perform music (in this case, the National Youth Orchestra) without instruments. Instead, Meredith asked the teens to use their mouths, hands, and feet to bellow, clap, and stomp their way through a mesmerizing 12-minute symphony.

Musicians, she suggests, have a tendency to hide behind their instruments. “Even at that age, as a player in an orchestra, you tend to be defined by your role: ‘I am a cellist’ or ‘I am a flute player’, but their sense of camaraderie, professionalism and teamwork was brilliant.” Instead of the self-separateness and egoism of playing this or that instrument in a defined category, the orchestra performed itself as a whole of connected, but individual, bodies.

Because of this kind of formal daring, Meredith now finds herself in demand by both the classical sphere and contemporary pop artists (for instance, she’s collaborated with voices such as Mira Calix and James Blake). For her, there’s no distinction between the classical and pop worlds. “I’ve never really seen them as different camps. My approach as a composer is always the same. I hear the ideas in my head and draw big graphic maps, and feed it all into Sibelius, a rather unglamorous program for notating crochets and quavers.”

Meredith’s latest project is a four song EP, _Black Prince Fury_ (out via Moshi Moshi), a work filled with Ableton-assisted electronica and thrilling, bombastic sounds, akin in spirit to the gargantuan beats favored by her fellow Scot, Hyperdub’s Rudi Zylgadlo. “His stuff is great. Theatrical. Musically adventurous.” Meredith’s own work is similarly minded. “I’m not interested in the fine tones and small gestures; I know I’m good at the bigger stuff. I like a transparency of structure, and not trying to trick the audience. It’s a similar thing with old school dance music: it’s about building, utilizing repetition, adding new elements along the way. Everyone knows the bass will \[eventually\] drop, or come back in, or explode. It’s about that sense of anticipation.”

* * *

Written by Charlotte Richardson Andrews

Photographed by Chiara Romagnoli

Photography: Chiara Romagnoli at ChiaraRomagnoli.com. Hair and Makeup: Annabel Callum at AnnabelCallum.com.

Scottish composer Anna Meredith’s adopted south London home, Camberwell, is dilapidated, hot to the point of exclamation and cramped with the noise of traffic-clogged roads—the kind of environs imposed by circumstance, rather than chosen. To get out of the heat, we adjourn to a small pub with old oak tables and order pints of lime and soda. Now not so repulsively hot, I realize maybe I’ve been a little too harsh to Camberwell. It boasts a pretty interesting list of people who call it home, like Florence Welch, of Florence + the Machine, playwrights Martin and John Michael McDonagh, and writer Zoe Williams. Maybe it’s close, crowded on the streets, and the cracked leather sofas in the pub look dreadfully uncomfortable, but in the countenance of this pub’s edifice, there’s a note of openness, as though willing to make room for any number of ideas.

“I feel comfy here,” Meredith says. “It’s an honest place.” Openness, like honesty, is integral to a sense of community, and, as she suggests, to good collaborations. “A few years back,” Meredith says, she and her composer friends who live in the area, “\[We\] started the Classical Composers Collective. We’d put on regularish gigs in the crypt of the jazz club down the road, which opened one night a week. Composers are often commissioned to write pieces, so you don’t always get to choose who you work with, or the criteria the piece is built around. Composing can be a very solitary thing, where you’re pacing around your room; the collective was our way of having a bit more control over what we do, and choosing our own collaborators.”

One possible way to proceed with Meredith’s compositions is to see how her command of influence opens up the formal and systematic aspects of classical music to multiple and different subversive elements. In turn, she’s able to relate the multiple to a unity. Her _Concerto for Beatboxer and Orchestra_, for which Meredith collaborated with U.K. beat-boxer, Shlomo, formalized the very improvisatory art of beat-boxing by notating every guttural, and the latest piece, _HandsFree_, which was performed recently at The Royal Albert Hall as part of BBC Proms 2012, furthered the subversive spirit by having an orchestra perform music (in this case, the National Youth Orchestra) without instruments. Instead, Meredith asked the teens to use their mouths, hands, and feet to bellow, clap, and stomp their way through a mesmerizing 12-minute symphony.

Musicians, she suggests, have a tendency to hide behind their instruments. “Even at that age, as a player in an orchestra, you tend to be defined by your role: ‘I am a cellist’ or ‘I am a flute player’, but their sense of camaraderie, professionalism and teamwork was brilliant.” Instead of the self-separateness and egoism of playing this or that instrument in a defined category, the orchestra performed itself as a whole of connected, but individual, bodies.

Because of this kind of formal daring, Meredith now finds herself in demand by both the classical sphere and contemporary pop artists (for instance, she’s collaborated with voices such as Mira Calix and James Blake). For her, there’s no distinction between the classical and pop worlds. “I’ve never really seen them as different camps. My approach as a composer is always the same. I hear the ideas in my head and draw big graphic maps, and feed it all into Sibelius, a rather unglamorous program for notating crochets and quavers.”

Meredith’s latest project is a four song EP, _Black Prince Fury_ (out via Moshi Moshi), a work filled with Ableton-assisted electronica and thrilling, bombastic sounds, akin in spirit to the gargantuan beats favored by her fellow Scot, Hyperdub’s Rudi Zylgadlo. “His stuff is great. Theatrical. Musically adventurous.” Meredith’s own work is similarly minded. “I’m not interested in the fine tones and small gestures; I know I’m good at the bigger stuff. I like a transparency of structure, and not trying to trick the audience. It’s a similar thing with old school dance music: it’s about building, utilizing repetition, adding new elements along the way. Everyone knows the bass will \[eventually\] drop, or come back in, or explode. It’s about that sense of anticipation.”

* * *

Written by Charlotte Richardson Andrews

Photographed by Chiara Romagnoli

Photography: Chiara Romagnoli at ChiaraRomagnoli.com. Hair and Makeup: Annabel Callum at AnnabelCallum.com.

Scottish composer Anna Meredith’s adopted south London home, Camberwell, is dilapidated, hot to the point of exclamation and cramped with the noise of traffic-clogged roads—the kind of environs imposed by circumstance, rather than chosen. To get out of the heat, we adjourn to a small pub with old oak tables and order pints of lime and soda. Now not so repulsively hot, I realize maybe I’ve been a little too harsh to Camberwell. It boasts a pretty interesting list of people who call it home, like Florence Welch, of Florence + the Machine, playwrights Martin and John Michael McDonagh, and writer Zoe Williams. Maybe it’s close, crowded on the streets, and the cracked leather sofas in the pub look dreadfully uncomfortable, but in the countenance of this pub’s edifice, there’s a note of openness, as though willing to make room for any number of ideas.

“I feel comfy here,” Meredith says. “It’s an honest place.” Openness, like honesty, is integral to a sense of community, and, as she suggests, to good collaborations. “A few years back,” Meredith says, she and her composer friends who live in the area, “\[We\] started the Classical Composers Collective. We’d put on regularish gigs in the crypt of the jazz club down the road, which opened one night a week. Composers are often commissioned to write pieces, so you don’t always get to choose who you work with, or the criteria the piece is built around. Composing can be a very solitary thing, where you’re pacing around your room; the collective was our way of having a bit more control over what we do, and choosing our own collaborators.”

One possible way to proceed with Meredith’s compositions is to see how her command of influence opens up the formal and systematic aspects of classical music to multiple and different subversive elements. In turn, she’s able to relate the multiple to a unity. Her _Concerto for Beatboxer and Orchestra_, for which Meredith collaborated with U.K. beat-boxer, Shlomo, formalized the very improvisatory art of beat-boxing by notating every guttural, and the latest piece, _HandsFree_, which was performed recently at The Royal Albert Hall as part of BBC Proms 2012, furthered the subversive spirit by having an orchestra perform music (in this case, the National Youth Orchestra) without instruments. Instead, Meredith asked the teens to use their mouths, hands, and feet to bellow, clap, and stomp their way through a mesmerizing 12-minute symphony.

Musicians, she suggests, have a tendency to hide behind their instruments. “Even at that age, as a player in an orchestra, you tend to be defined by your role: ‘I am a cellist’ or ‘I am a flute player’, but their sense of camaraderie, professionalism and teamwork was brilliant.” Instead of the self-separateness and egoism of playing this or that instrument in a defined category, the orchestra performed itself as a whole of connected, but individual, bodies.

Because of this kind of formal daring, Meredith now finds herself in demand by both the classical sphere and contemporary pop artists (for instance, she’s collaborated with voices such as Mira Calix and James Blake). For her, there’s no distinction between the classical and pop worlds. “I’ve never really seen them as different camps. My approach as a composer is always the same. I hear the ideas in my head and draw big graphic maps, and feed it all into Sibelius, a rather unglamorous program for notating crochets and quavers.”

Meredith’s latest project is a four song EP, _Black Prince Fury_ (out via Moshi Moshi), a work filled with Ableton-assisted electronica and thrilling, bombastic sounds, akin in spirit to the gargantuan beats favored by her fellow Scot, Hyperdub’s Rudi Zylgadlo. “His stuff is great. Theatrical. Musically adventurous.” Meredith’s own work is similarly minded. “I’m not interested in the fine tones and small gestures; I know I’m good at the bigger stuff. I like a transparency of structure, and not trying to trick the audience. It’s a similar thing with old school dance music: it’s about building, utilizing repetition, adding new elements along the way. Everyone knows the bass will \[eventually\] drop, or come back in, or explode. It’s about that sense of anticipation.”

* * *

Written by Charlotte Richardson Andrews

Photographed by Chiara Romagnoli

.jpg)