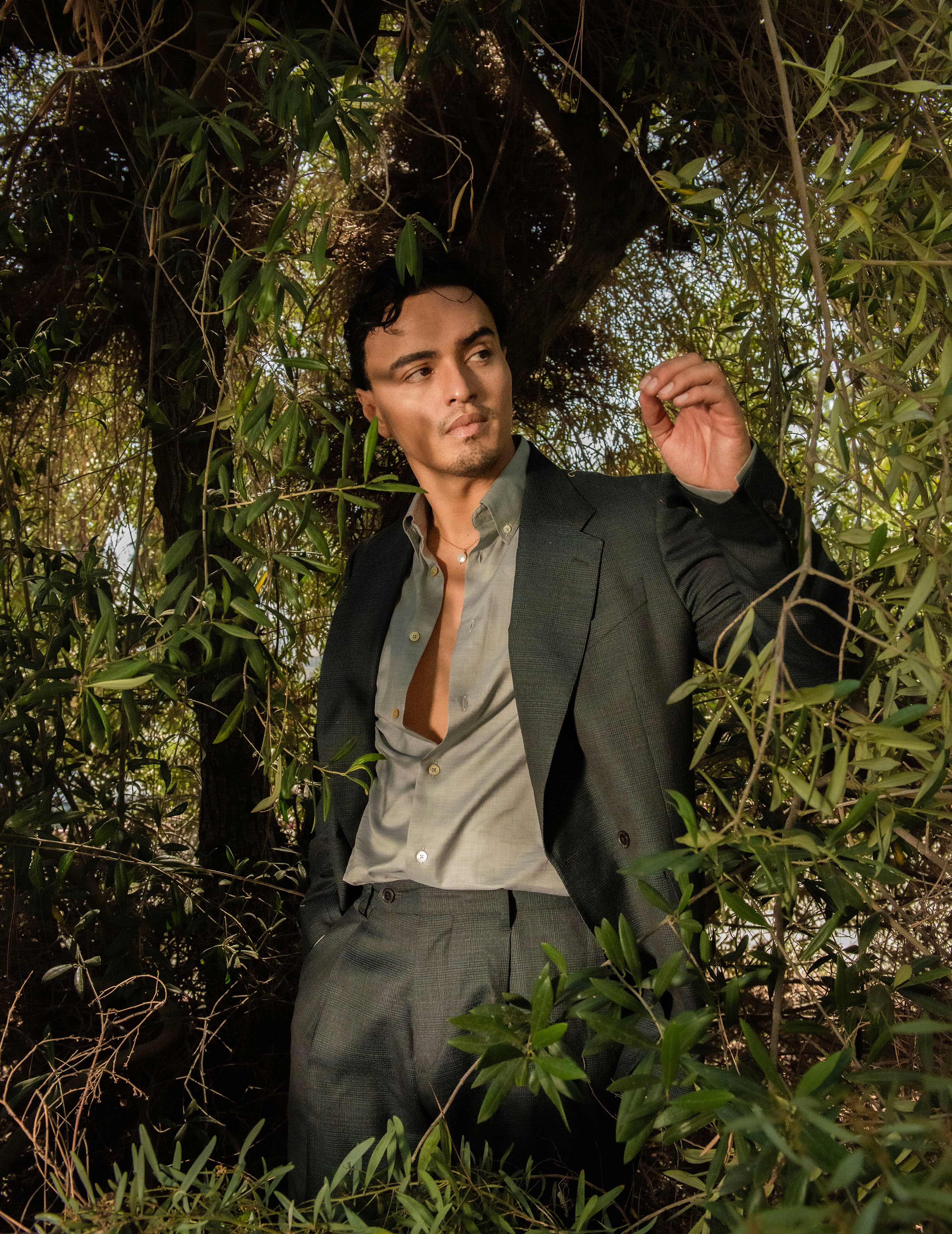

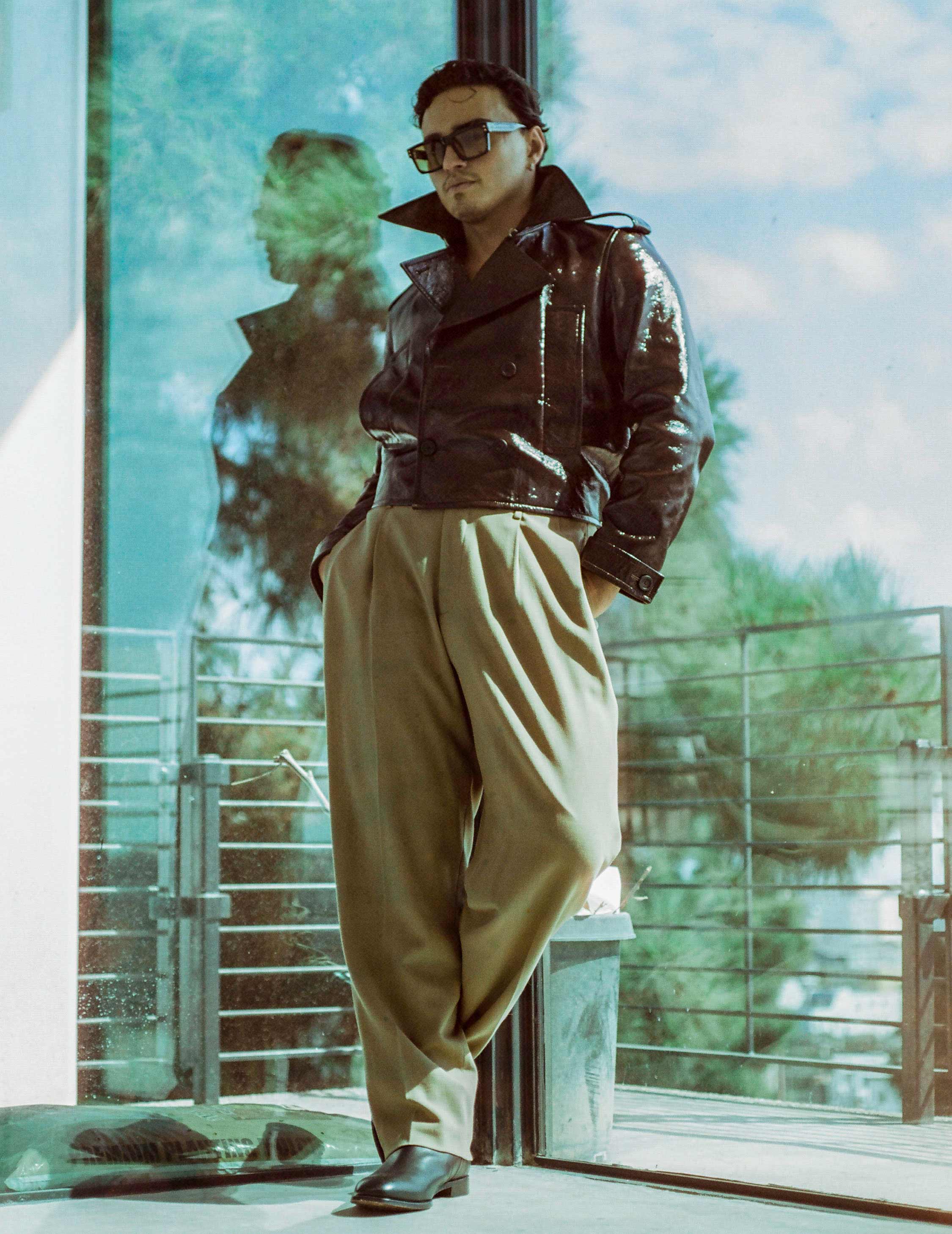

F L A U N T

“We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” This line, imparted by Joan Didion, sits at the curious intersection of elegy and commandment, a reminder that narrative is not an indulgence—it’s oxygen. It seems as though Tonatiuh has it etched into his heart, injecting him with a kind of voltage. For the Los Angeles-born actor, the dictum is muscle and marrow. Tonatiuh is an artist who carries story the way others carry breath—as survival, as resistance, as the scaffolding of identity.

When he opens our conversation, it is with a secret. “You’re my first,” he tells me, meaning that I am the first to know that he has flown into Nashville to receive the Rising Star Award at the Nashville Film Festival for his portrayal of Luis Molina in Kiss of the Spider Woman, in which he leads alongside Diego Luna and Jennifer Lopez. Adapted from Manuel Puig’s 1976 novel, the film traces unlikely intimacy between a Marxist revolutionary and a queer dreamer. It is a fitting choice of vehicle, because to play Molina is to play multiplicity itself: “It’s two people in two different eras, three different energies,” he explains. “Hyper-masculine classic Hollywood, something genderqueer and in the middle, and then full femme fantasy. It’s an actor’s dream.”

The character of Molina demands a kaleidoscopic actor. Tonatiuh delivers. He shrinks his body by nearly 50 pounds. He becomes a student of Gene Kelly’s carriage for Technicolor fantasia, and doesn’t hesitate to discard his studies for the brutal intimacy of the 1980s Argentinian prison cell. He spins Molina into something at once utterly specific and radically universal: a figure of camp and pain, defiance and fragility. “My mission statement was to bring as much dignity to Molina as possible,” he tells me. “To showcase their totality.”

That instinct—to collapse genders, eras, and queer archetypes into a singular role—is not a universally conjured instinct. The groundwork was laid in the LA area neighborhoods of Boyle Heights and West Covina, where Tonatiuh was raised, witnessing his mother transform women in a beauty salon chair, developing an understanding of how a mirror could rearrange reality. Even his name carried prophecy, awash in golden suns, though for years he shaved it down to “Matt” in schoolyards and audition rooms, experiencing the cost of survival through erasure. He would reclaim it later as a mono-moniker as the work expanded: he played a recurring role on television series Vida, appeared in limited series Angelyne alongside Emmy Rossum; in indies like Drunk Bus; in Netflix thriller Carry On alongside Taron Egerton and Jason Bateman. Each role proved a rehearsal in metamorphosis. Molina, then, is not anything new to Tonatiuh—they are the flowering of every prior transformation.

But the question remains: what does it mean to witness this performance now? In an era where audiences demand both spectacle and authentic confession, where identity is bungled as both market and mirror, what does Tonatiuh embody? Where do they surface in the triangulation of representation, authenticity, and worship?

To Tonatiuh, the answer is resisting taxonomy. “I am a creator who happens to be Latino, but I am not a Latino creator,” he insists. Hollywood loves genres; he refuses them, but he knows what visibility can do. After screenings, strangers confess to him: their coming-out stories, their migration odysseys, their buried fears. Molina becomes a conduit, a prism through which all may glimpse themselves. In that sense, the performance is less about identity than it is connection.

And yet, Tonatiuh is also at the crux of a cultural shift. In 2023, Latino box office spend exceeded the economy of New York City. These are tectonic facts. “Put some respect on our names,” he demands. “We’re wonderful and beautiful and diverse and passionate.” And isn’t that the heart of Didion’s line? Story as lifeline, story as dignifier. For Tonatiuh, cinema is not diversion but communion.

Which brings us back to Didion, as all good things do. We tell ourselves stories in order to live. If Didion stands correct, then what does Tonatiuh’s story tell us about living now? “I don’t think humans understand a world without a story,” he asserts. “We’re constantly telling ourselves stories every single day. What I’m proud of with this film is that we are telling a story that reminds us of who we are and what our values are, and it holds up a mirror to our own society, and makes us ask—is this how we want to live?”

Tonatiuh’s story tells us that we still seek mirrors. He knows we always will. In Tonatiuh’s hands, stories do not merely keep us alive. They ignite us.

Photographed by Selah Tennberg

Styled by Jay Hines

Written by Melanie Perez

Grooming: Frankie Payne at Opus Beauty

Styling Assistants: Michael Washington and Amiah Joy

Production Assistants: Ke’von Terry and Sophie Saunders