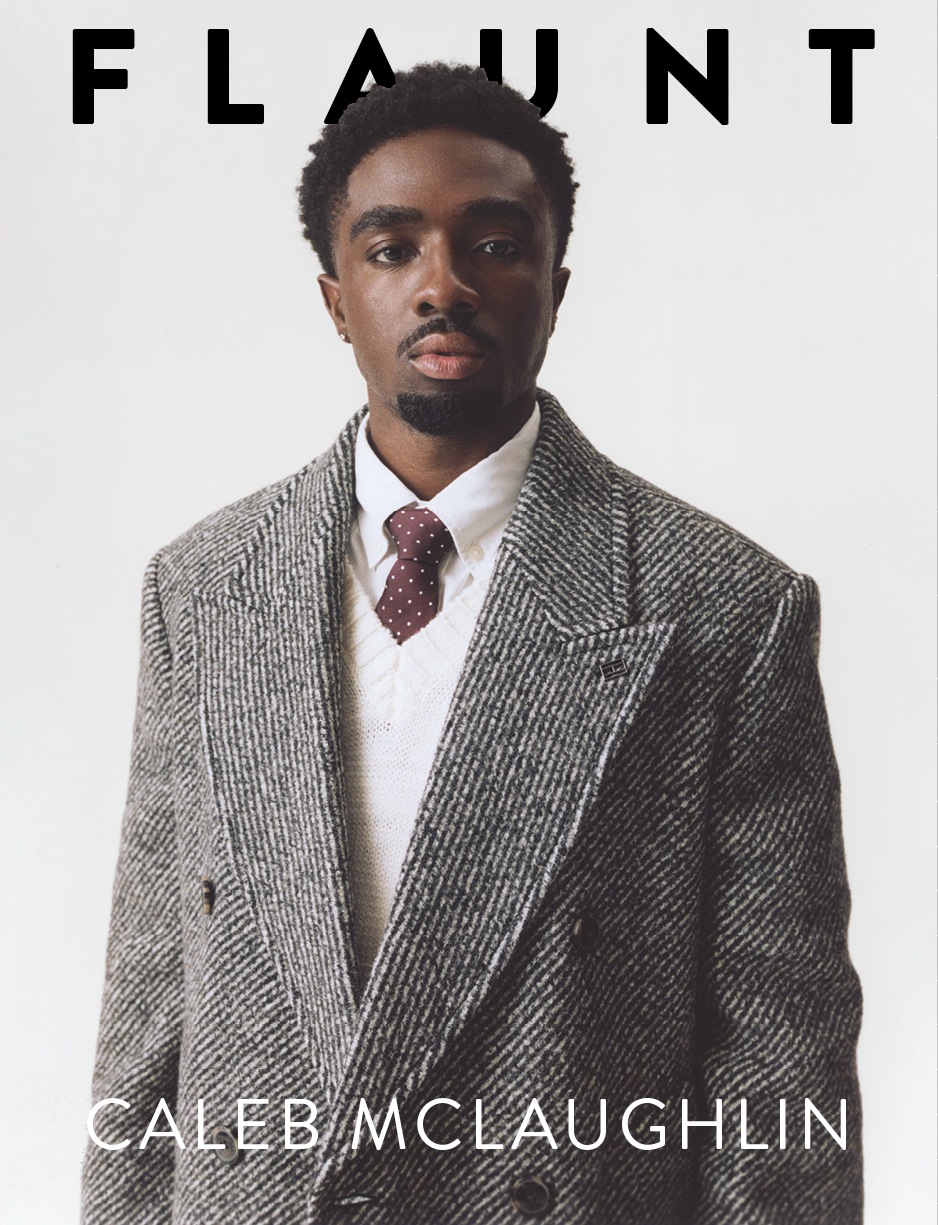

F L A U N T

In the beginning, there was repetition. Athletes call it training, monks call it prayer, and actors—those strange creatures of mimicry and faith—call it rehearsal.

Whatever the name, it’s the same creed: do it again, and again, until the doing becomes belief. If devotion had a sound, it might echo in the incandescent, precise tenor of Caleb McLaughlin, who speaks with the cadence of someone who’s been proving himself for 10 years and isn’t done yet.

If you were online in the summer of 2016, then you were lucky enough to witness the very inception of the global phenomenon that became Stranger Things. Because Stranger Things, now entering its final season, was never just a show—it was the upside-down world that colonized Netflix queues and Halloween costumes in equal measure, but it also served as a decade-long sociological experiment. A study in how nostalgia, internet fandom, and Dungeons & Dragons conspired to mint a generation of teenagers on camera while the rest of us watched like proud, slightly invasive aunts. McLaughlin didn’t simply grow up in front of us; he grew up for us—a generation raised to mistake access for intimacy.

And yet, he’s remarkably unwarped by it all. The 24-year-old has done 10 years of press, traveled everywhere humanly possible, and still remembers how to sound sincere. “Stranger Things inspired me to do more and be better,” he says. The word “better” appears often when McLaughlin speaks—a personal incantation against complacency. The word holds its weight when you’ve spent half your life measured by collective nostalgia.

Before Netflix, before Comic-Con, before nostalgia became a content economy, McLaughlin lived his life inside an ongoing exercise of refinement. The New York-raised performer learned rhythm before he learned rest—studying dance at the Harlem School of the Arts under the tutelage of Aubrey Lynch II, a former Lion King cast member who would later guide him to Broadway. At 10, McLaughlin became Young Simba: gold paint on his chest, a roar still forming in his throat. Eight shows a week taught him endurance before ego; applause was the reward for precision, not for having the flashiest hands in the room.

Acting, ironically, wasn’t even part of the original plan. “No, I didn’t always know,” he laughs when I ask if acting was ever an innate instinct. “When I was a kid, I wanted to be a bodybuilder. I wanted to play football, basketball. I wanted to have a garage band after watching Lemonade Mouth on Disney Channel. I wanted to be everything. Acting was the last thing on my list.” But even then, the throughline was discipline, every dream involving rigor. He pauses, then adds, “It was a calling. I think those are the callings—the ones you least expect to happen in your life.”

Maybe that’s the key to Caleb McLaughlin: he treats his vocation like an invitation—something to be answered, to be worked on. In an age where every creative impulse is designed to be hyperperceived, McLaughlin’s origin story unfolds in the supernaturally organic sense. Perhaps that’s why the question isn’t whether the last 10 years proved he could do it, but whether they proved he could keep doing it—without unraveling.

He talks about acting the way athletes talk about lactic acid: a necessary burn. “You train, you do reps, you push the muscle,” he says. “When I’m at the gym trying to get that last push-up in, I’m not like, ‘Okay, five is enough.’ I’m like, ‘I did 25 last week—let’s try 50.’ That’s what I want to do with my craft.” If you’re hearing echoes of the Jordan documentary or The Last Dance, you’re not wrong. He’s got that same monastic drive—the deadly earnest kind that would terrify you if it weren’t so charming.

McLaughlin has been famous longer than he hasn’t. There’s no before to measure against the after, no era of anonymity to romanticize. Fame didn’t interrupt his life. Rather, it engendered it, which might be why McLaughlin seems so uninterested in the usual stories of ascent or reverence. He’s lived too long within the walls of fame to mythologize it.

“I’m not trying to be anyone,” he says. “I admire a lot of people... but I never look at someone and say, ‘I want to be like them.’ I always want to be the best version of myself—the version that God wants me to be.” Every morning, he names the constants: “My mother, father, my brother, my sisters, even God—just grounding myself every morning and kind of just staying in reality.” It’s a statement that, in other mouths, might read sanctimonious. But McLaughlin says it with the ease of habit, symptomatic of staying steady while the ecosystem around him mutates at the speed of virality.

That equilibrium lands as almost countercultural. We live in an age when identity is expected to be constantly performative, algorithmically refreshed every six months. McLaughlin’s refusal to rebrand ten years in reads as radical common sense.

Still, resistance doesn’t mean withdrawal. He’s worked steadily across projects that mirror the multiplicity of boyhood and American ambition. In Concrete Cowboy, he played a restless teen confronting lineage and masculinity opposite Idris Elba. In Shooting Stars, he portrayed LeBron James’ high-school teammate, embodying the paradox of being excellent in someone else’s orbit. And in GOAT, the forthcoming animated sports drama, he’s set to examine ego and mentorship alongside basketball GOAT Stephen Curry—the anatomy of greatness itself. His roles form a quiet continuum of inquiry: How does one stay driven without being consumed? How does one honor ambition without worshipping it?

When he talks about GOAT, he smiles like someone who understands the joke baked into the title. “I don’t know if I can claim being the GOAT. It’s not about being the greatest of all time,” he says, “it’s about what happens when people start calling you that. It’s about ego. It’s about how you respond.” The answer, in his case, is simple: by working harder. Being better.

What’s striking is how much he’s managed to avoid the corrosion of spectacle. Many of his peers, also forged in the crucible of Stranger Things, have grown increasingly allergic to the public’s memory of their childhood selves. McLaughlin, instead, treats his origin story like a practice, something to tend rather than outrun. “Lucas represents power, resilience, love, passion. Every time I went into playing him, I thought about them [the fans], and wanted to portray his story and his life to the utmost, and I’ve enjoyed it for the past 10 years."

If Stranger Things was his initiation, these years after it feel like his mastery period. The show may have been a genre pastiche—a horror-fantasy about psychic kids and suburban dread—but its real experiment was temporal: could a generation raised by screens learn to perform sincerity? McLaughlin, it seems, can. “I just want to make people happy,” he says. It sounds disarmingly plain, almost anti-theatrical, but it’s not naïve. Happiness, for him, is alignment.

So, did the last decade prove he could do it? Maybe that’s the wrong question, or perhaps proof is the wrong metric. Proof, after all, belongs to the economy of clicks and charts. McLaughlin’s metric is quieter, less measurable. It’s the ability to keep doing something long after the audience has moved on—to find divinity in repetition. And he has.

What remains is neither moral nor motivational but empirical. Caleb McLaughlin has survived the great social experiment of modern fame with his curiosity intact. Earnest as ever, he’s what happens when discipline outlasts spectacle—when consistency becomes its own kind of rebellion.

“I mean, this is going to sound super cliché,” he says, “but it really is about your heart, your drive, and what you think about yourself. You don’t have to succumb to other people’s thoughts—because that happens a lot.” He pauses, then adds with quiet certainty: “As long as I keep studying my craft and doing what I love, I think I’ll be exactly where I’m meant to be.”

It’s an unflashy desire, and in a world that rewards spectacle, grounding himself in reality might be his fiercest gesture.

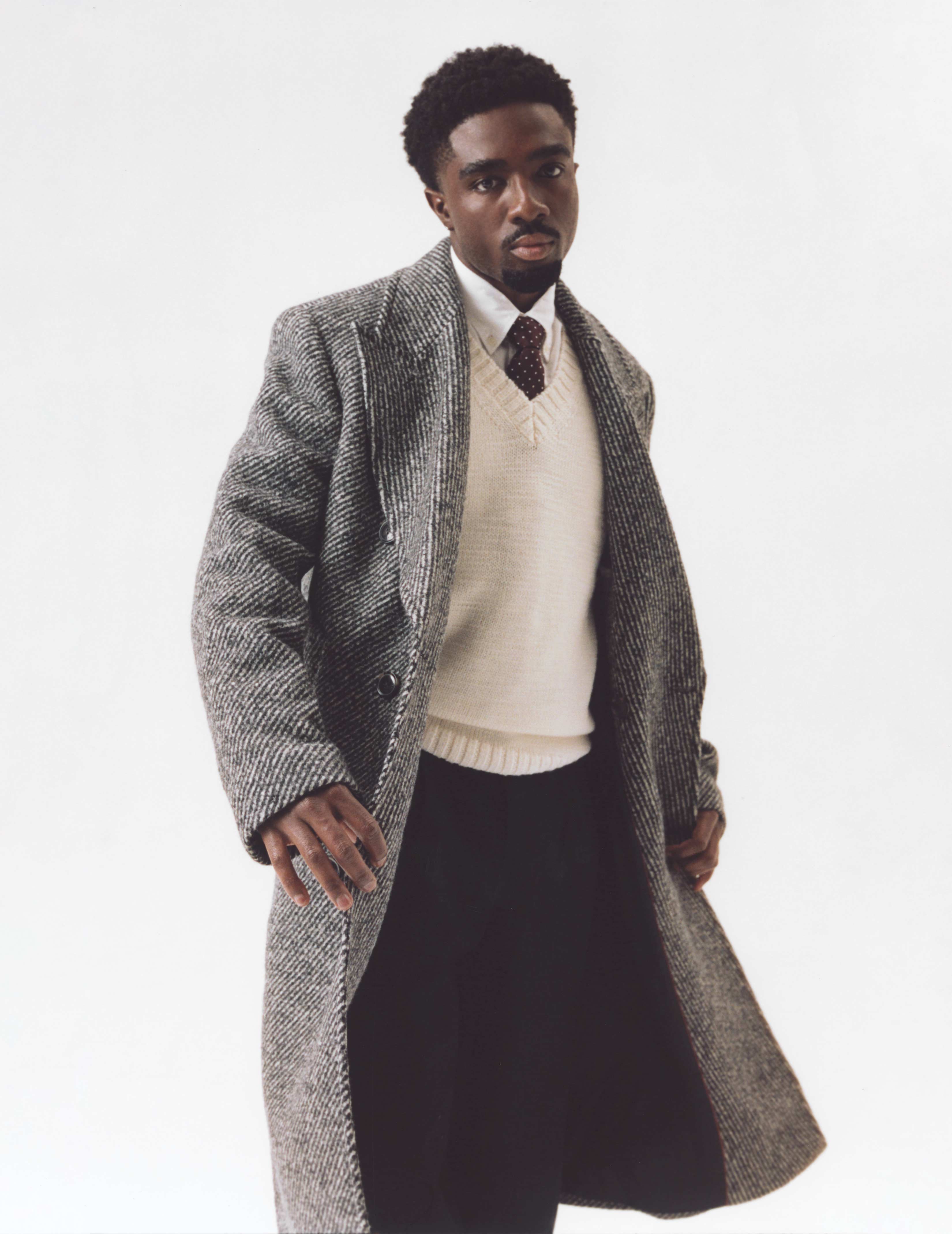

Photographed by Meg Young

Styled by Benjamin Holtrop

Written by Melanie Perez

Grooming: Jenna Nelson at The Wall Group

Photo Assistant: Matt Cluett

Styling Assistants: Emily Johnson, Leviticus Williams, Rasheed Kanbar

Production Assistants: Ke’von Terry and Sophie Saunders