Berlin in the winter is frigid. Outside temperatures drop well below freezing, regularly hovering around -10 degrees Celsius (that’s 14 degrees Fahrenheit). The polished concrete buildings blend into the snow and clouds. It’s stark.

In the winter of 2017, artist Michael Sailstorfer built a fire. His show _Hitzefrei_ consisted of six car frames painted flat black, with a large oven set into each chassis. A haphazard black chimney climbed from each car into the ceiling. Outside, the Köenig Galerie that held the show looked like a factory, smoke pluming from the roof.

“I was interested in this picture of a traffic jam,” Sailstorfer tells me from his Berlin studio. “Or a factory, and the kinetic energy of the car being translated into something else—heat. So, it had to be pretty warm in there.”

That’s an understatement. While outside was below freezing, Sailstorfer’s exhibition was 104 degrees Fahrenheit. “Almost claustrophobic,” he says with a wink.

\*\*\*

The mechanics and craft of the _Hitzefrei_ cars is impressive. In such a minimal space, Sailstorfer created a perfect visual metaphor for the modern urban environment: a smoking vehicle carcass, cleaned up nice for a gallery.

Sailstorfer’s talent as a craftsman and sculptor is undeniable. He’s been doing it since forever. His father owned a stone working business in Lower Bavaria, about an hour north of Munich. His father gained the business from his father. Sailstorfer grew up in that family workshop, building things from whatever was on the floor.

“That’s what I did a lot in my childhood,” he says. “Building stuff using materials just laying around—pieces of wood, pieces of stone, like whatever. As long as I can remember, I was spending time at the workshop.”

After high school, Sailstorfer took a year off. After that year, he still wasn’t sure what he wanted to do. He applied to a few schools, and his options narrowed down to architecture or art— both building, both mechanical, but very different headspaces. He went with art school. “I picked it because it’s more free and I can do whatever I like,” he says. He made a deal with his father—he’d “try the art thing,” but if he failed to make a living at it, he would do something else.

Turns out the Sailstorfers had nothing to worry about. By his sophomore year, their son was in the papers. His first show, _Herterichstraße 119_, consisted of a couch built out of materials from a demolished house. He got some pictures of the house before it was destroyed, and hung them above the piece. People responded, and he got some attention. “That was the starting point,” he says. “Well, _one_ starting point.” The next came only a few weeks later. The Munich Museum of Contemporary Art approached him to do a large installation outside of the museum. It had a real budget and a six-week timeline. He went for it, and created the piece “Und Sie Bewegt Sich Doch,” a model of the solar system made of cars, crumpled metal, streetlights, and other urban detritus. “That was the first museum thing,” he says, “That was in like several German newspapers. Then some galleries got interested...”

From the start, Sailstorfer had a very clear vision of what he wanted to do. “I was also willing to put a lot of hard work into it,” he says. “At the beginning I did all of the stuff with my own hands in the studio. Maybe an important thing was that I just wanted to do it. I knew I wanted it, and so I just did it.”

\* \* \*

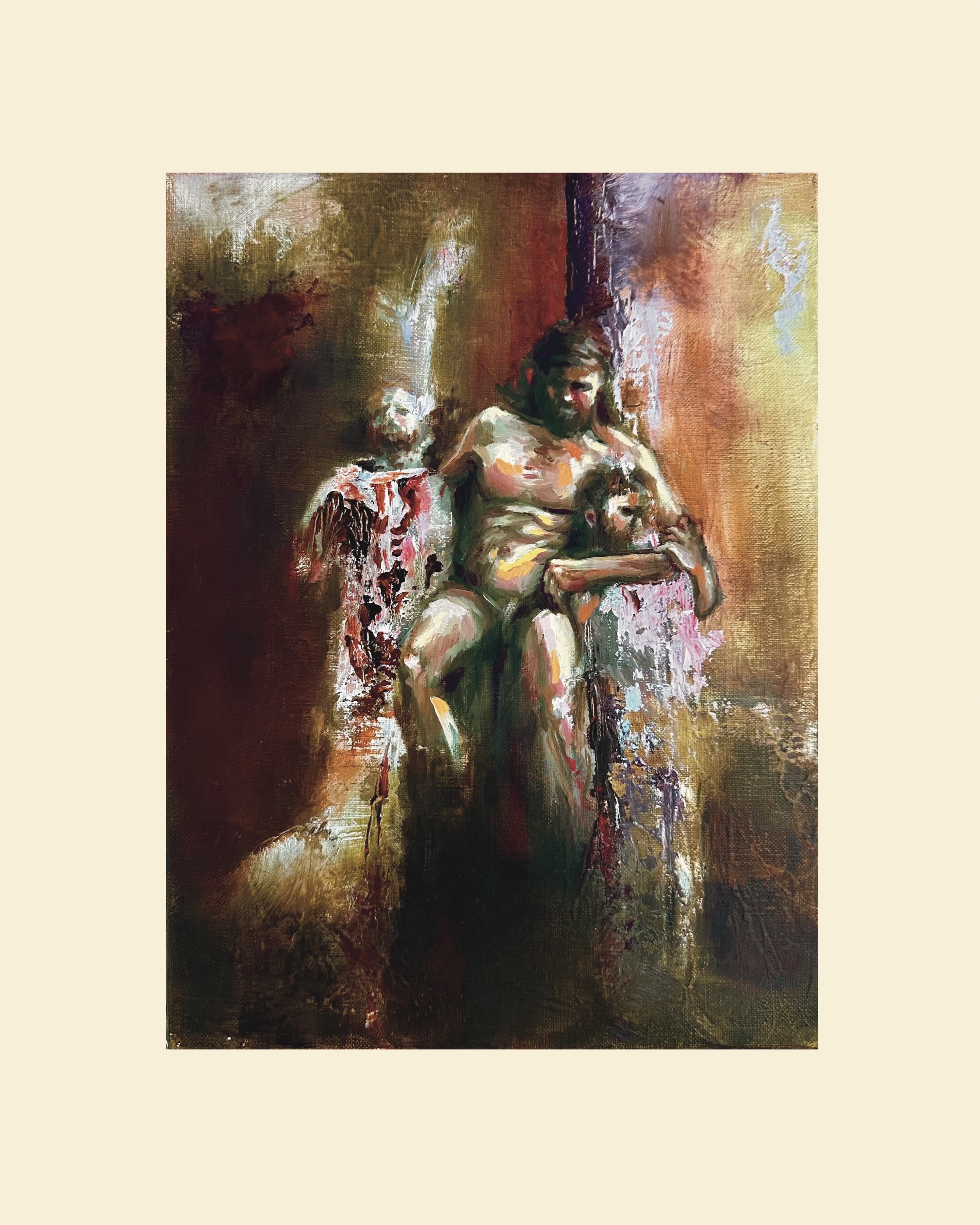

MICHAEL SAILSTORFER. “TEARCRACKER” (2018). C-PRINT. 20 7/8 × 15 3/4 INCHES. EDITION 1/10 + III AP. COURTESY THE ARTIST.

There’s a quote by Saint Francis of Assisi that’s become a bit of a cliché, but it goes, _He who works with his hands is a labor- er. He who works with his hands and his head is a craftsman. He who works with his hands and his head and his heart is an artist._ Sailstorfer’s hands, to start, are clearly present in his work. Everything he does is immaculately executed, and he’s a great example of how strong handiwork can lead to stronger conceptual work.

Back in the furnace of the Köenig Galerie in Berlin, a video is projected against the wall. It’s a single-shot of a rustic home somewhere in the European countryside. From the top of the frame, a single tear begins to fall. It looks like a cartoon, big and bulbous and blue, falling in slow motion. Once it makes contact with the house, however, it hits like a wrecking ball, and the roof crumbles under its weight. Over time, tears continue to fall, until all that remains is rubble.

“I think it was like half a year of planning,” he says. “I put three cranes around the house, and we dropped those cast-iron tears, each as heavy as around 2,000 kilos, on the house for about two days until it was completely destroyed... Then a big part of the piece was the post-production, taking away the crane cables and the shadows of the cranes. Post-production took a huge part of the production of the piece.”

The resulting video, “Tränen,” is well-produced and highly conceptual. The practical skill needed for creating this, from the cast-iron tears to post-production, showcases Sailstorfer’s deep toolbox. The conceptual elements of it, however, show off Sailstorfer’s ability to wrestle with complex themes. “I think ‘Tränen’ was generated more from a feeling, a feeling connected to a picture, I can’t tell you exactly what it means. But, on the one hand, it has to do with sadness, and on the other it has to do with slapstick.”

\*\*\*

So much of Sailstorfer’s work happens in this intersection of sadness and slapstick. His 2018 London show _Tear Show_ held around thirty paintings of tears. The floor was covered in differ- ent pieces of drum sets, each with a mechanism that triggered drum sticks to play in discordant rhythms (the drum piece is called _D.A.V.E.L.O.M.B.A.R.D.O._, after the drummer of Slayer). You can call the drums cacophony, creating the same claustrophobic effect of the heat in _Hitzefrei._ You can also call it slapstick, a bunch of competing rhythms stumbling over each other while the viewer tries to take in the more traditional paintings and sculptures of tears.

“I think for a piece to be present in a space and present for the viewer, it needs to have something like sound or smell to underline that presence. The viewer can’t just roll over and keep on talking during an opening,” he says. “But, the piece should also be there and have its own language. That’s why you some- times need another element...I think there is a very good quote by Andy Warhol, he says, ‘I’m a very shy person, but when I’m entering a room I want to have as much attention as some very extroverted person, that’s why I’m wearing a lot of perfume.’ That’s what I’m doing as well with the pieces. I’m giving them more space by adding another level to it.”

Part of why _Tear Show_ works is the mastery of the traditional elements. The paintings are wonderful; bold screen- prints of the same tear in different muted color combinations. There’s a group of blown-glass tears that all lay on the same tilt, just so. Sailstorfer does not use traditional techniques in order to sneak in modern ones, nor does he use modern flash to highlight the traditional. The traditional techniques and the modern (robotics, virtual reality, software) hold equal weight in his work. He has a feeling he wants to convey, and over the years he has curated an extensive toolbox in order to accomplish that. “I’m interested in virtual reality,” he says, “Because it opens up a completely new dimension and a completely new universe to be filled with new artistic ideas. But I’m also interested in very traditional techniques, like traditional sculpture or casting. I wouldn’t limit myself to anything. I think it’s always about the idea, or concept, or image. I’m looking for the best possible way to bring it to life.”

MICHAEL SAILSTORFER. “HEAVY TEAR 27 CHANEL 454 JEAN” (2018). LEAD, LIPSTICK. 19 5/8 × 15 3/4 × 3/4 INCHES. COURTESY THE ARTIST.

For Sailstorfer, technique is technique. It doesn’t matter if it’s as old as glassblowing or as new as robotics. It’s whatever does the job, whatever results in work that is vital and impactful enough to pierce through the noise that characterizes modern life and to hit the viewer. “I think the work has to be very substantial,” he says. “It has to be strong and substantial so that it can stand next to the headlines that we’re inundated with every day... The longer I’m working into the field of contemporary art, the more I think it should be very substantial and less about decoration. I think now’s the time to focus on the conceptual side of the work.”

Currently, Sailstorfer is working on several projects. He has a Munich show at BNKR from January 31st through April 12, 2019, featuring “Tränen_._” He has a show at the Perrotin in New York from March 2nd to April 13th, featuring the _Heavy Tears_ paintings. He’s working on a large project in Norway, where three sculptures will slowly dissolve over the period of the exhibition. Bit by bit, Sailstorfer’s work is moving away from static pieces towards dynamic, ephemeral ones. We, as the audience, are being granted more and more access to his head.

\* \* \*

Strong craftsmanship, intriguing concepts—these are important aspects of being a career artist in general. What separates Sailstorfer is his heart. His work often involves urban material; cars, pipes, a giant popcorn machine. “I think we live in a period where you’re surrounded by these things, like cars, streets lamps, roads, houses,” he says. “I’ve mostly lived in cities, and I always tend to just use what surrounds me and use it to build new stories.”

This idea of using whatever is around him calls back to his early days in his father’s workshop, building things out of whatever was on the floor. The urban environments that surround him now are often filled with the kind of cross-technique methodology found in his work, an interplay of solutions that work best. Hundred-year-old craftsman homes will have solar panels on the roof, old brick and new screens. Often, the interactions of materials, and how people respond to them, are what determine the vibe of a city or neighborhood. Berlin is cold and concrete, Los Angeles is hot and wooden, and you can feel that difference. This is what Sailstorfer’s work creates on a small-scale. He combines new technology and old techniques, adds ephemeral elements of heat, sound, smell, and he turns an art space into a microcosm. Pictures alone cannot do his shows the justice they deserve.

Ultimately, what sets Sailstorfer apart is his ability to com-bine so many elements of his life and his world into his work. He’s a gifted craftsman and an insightful conceptualist, but more importantly, he’s himself. He doesn’t try to be more than that.

“I think for me it’s important that the work is very personal,” he says. “It has something to do with my own history, and with my situation I’m in, in life right now. When I start a project, I ask myself, ‘Why is it important to me at this certain moment?’ And that’s an important thing—how personal the work is, how autobiographical it is. I think that’s probably the thing that makes me do things, makes me want to realize things.”

Here, we uncover the heart of Michael Sailstorfer. His head and his hands are readily present in his work. But, underneath the 100+ degree rooms and crashing cast-iron tears, beats the heart of the kid that grew up in a stone workshop outside Munich. If you lean in, you can hear it, and suddenly everything ties together.

MICHAEL SAILSTORFER. “TEARCRACKER” (2018). C-PRINT. 20 7/8 × 15 3/4 INCHES. EDITION 1/10 + III AP. COURTESY THE ARTIST.

There’s a quote by Saint Francis of Assisi that’s become a bit of a cliché, but it goes, _He who works with his hands is a labor- er. He who works with his hands and his head is a craftsman. He who works with his hands and his head and his heart is an artist._ Sailstorfer’s hands, to start, are clearly present in his work. Everything he does is immaculately executed, and he’s a great example of how strong handiwork can lead to stronger conceptual work.

Back in the furnace of the Köenig Galerie in Berlin, a video is projected against the wall. It’s a single-shot of a rustic home somewhere in the European countryside. From the top of the frame, a single tear begins to fall. It looks like a cartoon, big and bulbous and blue, falling in slow motion. Once it makes contact with the house, however, it hits like a wrecking ball, and the roof crumbles under its weight. Over time, tears continue to fall, until all that remains is rubble.

“I think it was like half a year of planning,” he says. “I put three cranes around the house, and we dropped those cast-iron tears, each as heavy as around 2,000 kilos, on the house for about two days until it was completely destroyed... Then a big part of the piece was the post-production, taking away the crane cables and the shadows of the cranes. Post-production took a huge part of the production of the piece.”

The resulting video, “Tränen,” is well-produced and highly conceptual. The practical skill needed for creating this, from the cast-iron tears to post-production, showcases Sailstorfer’s deep toolbox. The conceptual elements of it, however, show off Sailstorfer’s ability to wrestle with complex themes. “I think ‘Tränen’ was generated more from a feeling, a feeling connected to a picture, I can’t tell you exactly what it means. But, on the one hand, it has to do with sadness, and on the other it has to do with slapstick.”

\*\*\*

So much of Sailstorfer’s work happens in this intersection of sadness and slapstick. His 2018 London show _Tear Show_ held around thirty paintings of tears. The floor was covered in differ- ent pieces of drum sets, each with a mechanism that triggered drum sticks to play in discordant rhythms (the drum piece is called _D.A.V.E.L.O.M.B.A.R.D.O._, after the drummer of Slayer). You can call the drums cacophony, creating the same claustrophobic effect of the heat in _Hitzefrei._ You can also call it slapstick, a bunch of competing rhythms stumbling over each other while the viewer tries to take in the more traditional paintings and sculptures of tears.

“I think for a piece to be present in a space and present for the viewer, it needs to have something like sound or smell to underline that presence. The viewer can’t just roll over and keep on talking during an opening,” he says. “But, the piece should also be there and have its own language. That’s why you some- times need another element...I think there is a very good quote by Andy Warhol, he says, ‘I’m a very shy person, but when I’m entering a room I want to have as much attention as some very extroverted person, that’s why I’m wearing a lot of perfume.’ That’s what I’m doing as well with the pieces. I’m giving them more space by adding another level to it.”

Part of why _Tear Show_ works is the mastery of the traditional elements. The paintings are wonderful; bold screen- prints of the same tear in different muted color combinations. There’s a group of blown-glass tears that all lay on the same tilt, just so. Sailstorfer does not use traditional techniques in order to sneak in modern ones, nor does he use modern flash to highlight the traditional. The traditional techniques and the modern (robotics, virtual reality, software) hold equal weight in his work. He has a feeling he wants to convey, and over the years he has curated an extensive toolbox in order to accomplish that. “I’m interested in virtual reality,” he says, “Because it opens up a completely new dimension and a completely new universe to be filled with new artistic ideas. But I’m also interested in very traditional techniques, like traditional sculpture or casting. I wouldn’t limit myself to anything. I think it’s always about the idea, or concept, or image. I’m looking for the best possible way to bring it to life.”

MICHAEL SAILSTORFER. “TEARCRACKER” (2018). C-PRINT. 20 7/8 × 15 3/4 INCHES. EDITION 1/10 + III AP. COURTESY THE ARTIST.

There’s a quote by Saint Francis of Assisi that’s become a bit of a cliché, but it goes, _He who works with his hands is a labor- er. He who works with his hands and his head is a craftsman. He who works with his hands and his head and his heart is an artist._ Sailstorfer’s hands, to start, are clearly present in his work. Everything he does is immaculately executed, and he’s a great example of how strong handiwork can lead to stronger conceptual work.

Back in the furnace of the Köenig Galerie in Berlin, a video is projected against the wall. It’s a single-shot of a rustic home somewhere in the European countryside. From the top of the frame, a single tear begins to fall. It looks like a cartoon, big and bulbous and blue, falling in slow motion. Once it makes contact with the house, however, it hits like a wrecking ball, and the roof crumbles under its weight. Over time, tears continue to fall, until all that remains is rubble.

“I think it was like half a year of planning,” he says. “I put three cranes around the house, and we dropped those cast-iron tears, each as heavy as around 2,000 kilos, on the house for about two days until it was completely destroyed... Then a big part of the piece was the post-production, taking away the crane cables and the shadows of the cranes. Post-production took a huge part of the production of the piece.”

The resulting video, “Tränen,” is well-produced and highly conceptual. The practical skill needed for creating this, from the cast-iron tears to post-production, showcases Sailstorfer’s deep toolbox. The conceptual elements of it, however, show off Sailstorfer’s ability to wrestle with complex themes. “I think ‘Tränen’ was generated more from a feeling, a feeling connected to a picture, I can’t tell you exactly what it means. But, on the one hand, it has to do with sadness, and on the other it has to do with slapstick.”

\*\*\*

So much of Sailstorfer’s work happens in this intersection of sadness and slapstick. His 2018 London show _Tear Show_ held around thirty paintings of tears. The floor was covered in differ- ent pieces of drum sets, each with a mechanism that triggered drum sticks to play in discordant rhythms (the drum piece is called _D.A.V.E.L.O.M.B.A.R.D.O._, after the drummer of Slayer). You can call the drums cacophony, creating the same claustrophobic effect of the heat in _Hitzefrei._ You can also call it slapstick, a bunch of competing rhythms stumbling over each other while the viewer tries to take in the more traditional paintings and sculptures of tears.

“I think for a piece to be present in a space and present for the viewer, it needs to have something like sound or smell to underline that presence. The viewer can’t just roll over and keep on talking during an opening,” he says. “But, the piece should also be there and have its own language. That’s why you some- times need another element...I think there is a very good quote by Andy Warhol, he says, ‘I’m a very shy person, but when I’m entering a room I want to have as much attention as some very extroverted person, that’s why I’m wearing a lot of perfume.’ That’s what I’m doing as well with the pieces. I’m giving them more space by adding another level to it.”

Part of why _Tear Show_ works is the mastery of the traditional elements. The paintings are wonderful; bold screen- prints of the same tear in different muted color combinations. There’s a group of blown-glass tears that all lay on the same tilt, just so. Sailstorfer does not use traditional techniques in order to sneak in modern ones, nor does he use modern flash to highlight the traditional. The traditional techniques and the modern (robotics, virtual reality, software) hold equal weight in his work. He has a feeling he wants to convey, and over the years he has curated an extensive toolbox in order to accomplish that. “I’m interested in virtual reality,” he says, “Because it opens up a completely new dimension and a completely new universe to be filled with new artistic ideas. But I’m also interested in very traditional techniques, like traditional sculpture or casting. I wouldn’t limit myself to anything. I think it’s always about the idea, or concept, or image. I’m looking for the best possible way to bring it to life.”

MICHAEL SAILSTORFER. “HEAVY TEAR 27 CHANEL 454 JEAN” (2018). LEAD, LIPSTICK. 19 5/8 × 15 3/4 × 3/4 INCHES. COURTESY THE ARTIST.

For Sailstorfer, technique is technique. It doesn’t matter if it’s as old as glassblowing or as new as robotics. It’s whatever does the job, whatever results in work that is vital and impactful enough to pierce through the noise that characterizes modern life and to hit the viewer. “I think the work has to be very substantial,” he says. “It has to be strong and substantial so that it can stand next to the headlines that we’re inundated with every day... The longer I’m working into the field of contemporary art, the more I think it should be very substantial and less about decoration. I think now’s the time to focus on the conceptual side of the work.”

Currently, Sailstorfer is working on several projects. He has a Munich show at BNKR from January 31st through April 12, 2019, featuring “Tränen_._” He has a show at the Perrotin in New York from March 2nd to April 13th, featuring the _Heavy Tears_ paintings. He’s working on a large project in Norway, where three sculptures will slowly dissolve over the period of the exhibition. Bit by bit, Sailstorfer’s work is moving away from static pieces towards dynamic, ephemeral ones. We, as the audience, are being granted more and more access to his head.

\* \* \*

Strong craftsmanship, intriguing concepts—these are important aspects of being a career artist in general. What separates Sailstorfer is his heart. His work often involves urban material; cars, pipes, a giant popcorn machine. “I think we live in a period where you’re surrounded by these things, like cars, streets lamps, roads, houses,” he says. “I’ve mostly lived in cities, and I always tend to just use what surrounds me and use it to build new stories.”

This idea of using whatever is around him calls back to his early days in his father’s workshop, building things out of whatever was on the floor. The urban environments that surround him now are often filled with the kind of cross-technique methodology found in his work, an interplay of solutions that work best. Hundred-year-old craftsman homes will have solar panels on the roof, old brick and new screens. Often, the interactions of materials, and how people respond to them, are what determine the vibe of a city or neighborhood. Berlin is cold and concrete, Los Angeles is hot and wooden, and you can feel that difference. This is what Sailstorfer’s work creates on a small-scale. He combines new technology and old techniques, adds ephemeral elements of heat, sound, smell, and he turns an art space into a microcosm. Pictures alone cannot do his shows the justice they deserve.

Ultimately, what sets Sailstorfer apart is his ability to com-bine so many elements of his life and his world into his work. He’s a gifted craftsman and an insightful conceptualist, but more importantly, he’s himself. He doesn’t try to be more than that.

“I think for me it’s important that the work is very personal,” he says. “It has something to do with my own history, and with my situation I’m in, in life right now. When I start a project, I ask myself, ‘Why is it important to me at this certain moment?’ And that’s an important thing—how personal the work is, how autobiographical it is. I think that’s probably the thing that makes me do things, makes me want to realize things.”

Here, we uncover the heart of Michael Sailstorfer. His head and his hands are readily present in his work. But, underneath the 100+ degree rooms and crashing cast-iron tears, beats the heart of the kid that grew up in a stone workshop outside Munich. If you lean in, you can hear it, and suddenly everything ties together.

MICHAEL SAILSTORFER. “HEAVY TEAR 27 CHANEL 454 JEAN” (2018). LEAD, LIPSTICK. 19 5/8 × 15 3/4 × 3/4 INCHES. COURTESY THE ARTIST.

For Sailstorfer, technique is technique. It doesn’t matter if it’s as old as glassblowing or as new as robotics. It’s whatever does the job, whatever results in work that is vital and impactful enough to pierce through the noise that characterizes modern life and to hit the viewer. “I think the work has to be very substantial,” he says. “It has to be strong and substantial so that it can stand next to the headlines that we’re inundated with every day... The longer I’m working into the field of contemporary art, the more I think it should be very substantial and less about decoration. I think now’s the time to focus on the conceptual side of the work.”

Currently, Sailstorfer is working on several projects. He has a Munich show at BNKR from January 31st through April 12, 2019, featuring “Tränen_._” He has a show at the Perrotin in New York from March 2nd to April 13th, featuring the _Heavy Tears_ paintings. He’s working on a large project in Norway, where three sculptures will slowly dissolve over the period of the exhibition. Bit by bit, Sailstorfer’s work is moving away from static pieces towards dynamic, ephemeral ones. We, as the audience, are being granted more and more access to his head.

\* \* \*

Strong craftsmanship, intriguing concepts—these are important aspects of being a career artist in general. What separates Sailstorfer is his heart. His work often involves urban material; cars, pipes, a giant popcorn machine. “I think we live in a period where you’re surrounded by these things, like cars, streets lamps, roads, houses,” he says. “I’ve mostly lived in cities, and I always tend to just use what surrounds me and use it to build new stories.”

This idea of using whatever is around him calls back to his early days in his father’s workshop, building things out of whatever was on the floor. The urban environments that surround him now are often filled with the kind of cross-technique methodology found in his work, an interplay of solutions that work best. Hundred-year-old craftsman homes will have solar panels on the roof, old brick and new screens. Often, the interactions of materials, and how people respond to them, are what determine the vibe of a city or neighborhood. Berlin is cold and concrete, Los Angeles is hot and wooden, and you can feel that difference. This is what Sailstorfer’s work creates on a small-scale. He combines new technology and old techniques, adds ephemeral elements of heat, sound, smell, and he turns an art space into a microcosm. Pictures alone cannot do his shows the justice they deserve.

Ultimately, what sets Sailstorfer apart is his ability to com-bine so many elements of his life and his world into his work. He’s a gifted craftsman and an insightful conceptualist, but more importantly, he’s himself. He doesn’t try to be more than that.

“I think for me it’s important that the work is very personal,” he says. “It has something to do with my own history, and with my situation I’m in, in life right now. When I start a project, I ask myself, ‘Why is it important to me at this certain moment?’ And that’s an important thing—how personal the work is, how autobiographical it is. I think that’s probably the thing that makes me do things, makes me want to realize things.”

Here, we uncover the heart of Michael Sailstorfer. His head and his hands are readily present in his work. But, underneath the 100+ degree rooms and crashing cast-iron tears, beats the heart of the kid that grew up in a stone workshop outside Munich. If you lean in, you can hear it, and suddenly everything ties together.

.JPG)

.jpg)