Photographed by Franck Sauvaire

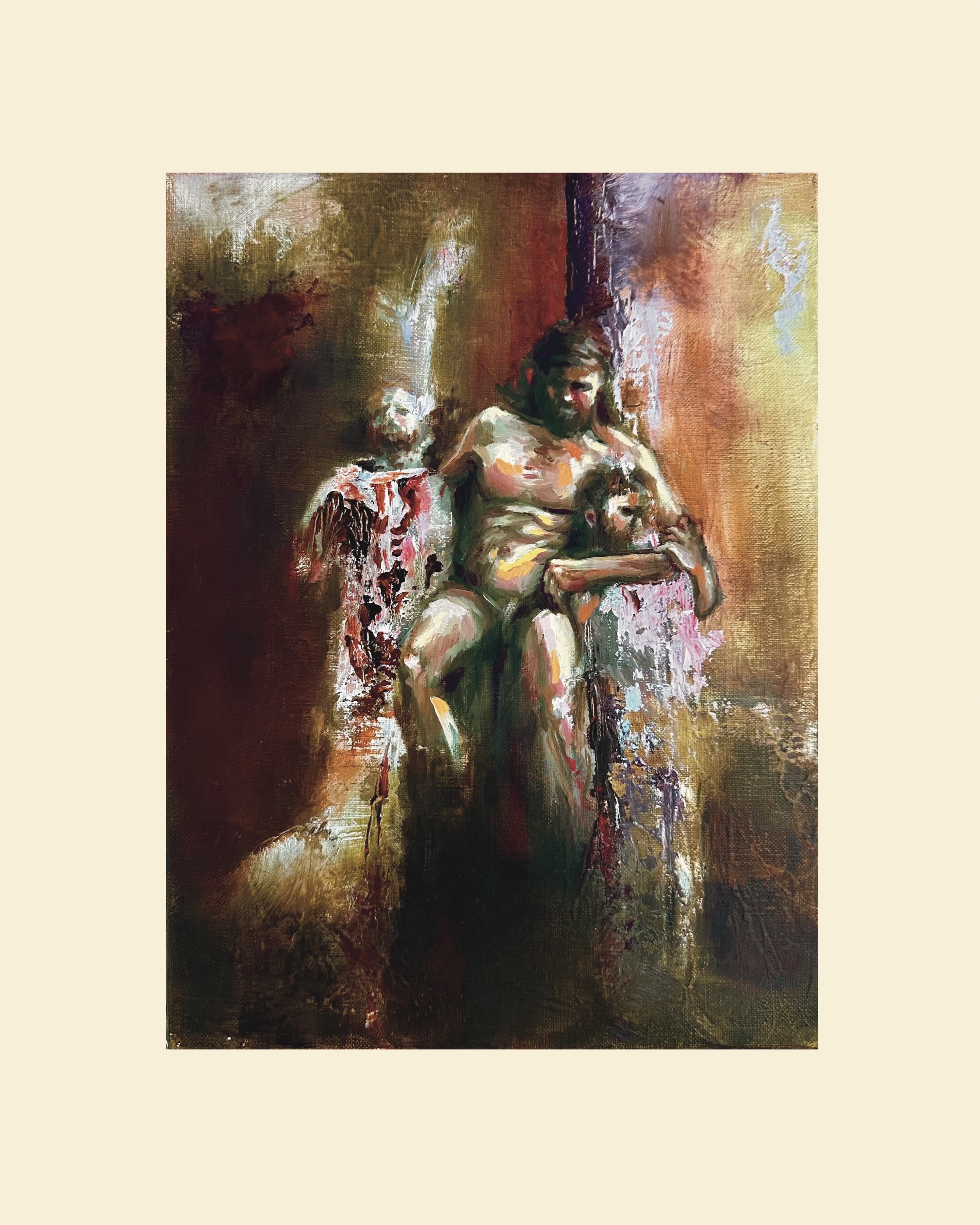

I meet Kindness, a.k.a. Adam Bainbridge, at Robin Bell’s photography print studio, an address nestled in a leafy mews behind the bustle and fruit-stacked stalls of West London’s North End Road market. Bell is one of very few professionals still faithfully hand-processing and printing black-and-white photography, a practice that Bainbridge—who used a cadre of analogue synths to make his debut Polydor album, _World, You Need a Change Of Mind_—finds an artistic affinity with. It’s a compact studio, scented with the chemical waft of developer solution, its white washed walls hung with monochrome prints by Richard Avedon and Bill Brandt. Behind the stiff black curtain entrance to the darkroom, we stand in dull red light, peering around Bell as he dunks the first of Bainbridge’s experimental photographs in trays of solution. Bainbridge—tall, tanned, whippet-thin and turned out in frayed denim shorts and loose shirt—is here to tinker with potential cover art for his next single.

Pinning down the artist, who’s returned to London after a stay in Berlin, was tricky. _World…_, a jazzy, wistfully soulful electro-funk work recorded in Paris with house maestro Philippe Zdar and released earlier this year to largely favorable acclaim, introduced Bainbridge to an exacting press, and he’s particular now about who he’ll talk to, preferring “intelligent, ethical, political, feminist” leaning publications. His penchant for covering obscure pop songs have been (mis)read by some as ironic homage, while others have taken umbrage at his music videos, seeing a pretentiousness in what he sees as a “childlike” enthusiasm for musical expression. We step out onto the cobbled mews lane to discuss this, taking mugs of hot tea out with us to perch on an adjacent wooden bench, shaded from the occasional patter of summer rain by a sweep of greenery spilling down from a window box above. There is, he says, in a deep, steady and clipped tone, sweeping that long cascade of hazel hair out of his eyes, a “distinct camp of (press) people who find it hard to appreciate innocence in pop music, or are confused that it might even exist.”

Pop, and its sprawling evolution, is of deep interest to Bainbridge. His latest video, for the song “House,” sees the singer in a sharp black suit and tie, sat in front of a retro synthesizer and quoting a Leonard Bernstein monologue from the 1967 CBS special _Inside Pop: The Rock Revolution_. “‘Pop Music is the only form of music that’s been made by, for, and about the kids.’ I looked at that line specifically, because modern pop is still made _for_ a youth audience, but its not really made _by_ that audience, or with their best intentions at heart. Once upon a time it was a platform for youth culture; now it’s just a way to steal their money.” Bainbridge seems genuinely concerned about the current state of pop music. “Its gone to a much darker, exploitative place than it was in Bernstein’s day,” he says, thoughtfully. “Youth culture expresses itself through the internet now; it doesn’t need punk, psychedelic, or disco to express its liberation the way it once did.”

It’s this fascination with the internet’s effect on pop, and the world before it, that’s led Bainbridge to his next project. Instead of hatching album number two (or three, if one counts the 2007 Philadelphia-based artist residency that produced his first, unofficial album, _Live In Philly_), he’s swapping mediums for a spell, and has applied for arts funding to finance a film project he’s been dreaming up. “At Glastonbury festival \[which began in the ’70s\], prior to the internet and mobile phones, teenagers would come, and have too good a time, and then lose their minds and forget where they lived. It turns out there was a chap who’s responsibility was to work out where in England these teenagers may have come from—based on their accent—and then drive them around the country, helping them to find their home.” It’s an eccentric, typically retrospective subject matter, and one that seems entirely fitting for this analogue-loving, romantic sifter of vintage pop annals.

Written by Charlotte Richardson Andrews

Photographed by Franck Sauvaire

I meet Kindness, a.k.a. Adam Bainbridge, at Robin Bell’s photography print studio, an address nestled in a leafy mews behind the bustle and fruit-stacked stalls of West London’s North End Road market. Bell is one of very few professionals still faithfully hand-processing and printing black-and-white photography, a practice that Bainbridge—who used a cadre of analogue synths to make his debut Polydor album, _World, You Need a Change Of Mind_—finds an artistic affinity with. It’s a compact studio, scented with the chemical waft of developer solution, its white washed walls hung with monochrome prints by Richard Avedon and Bill Brandt. Behind the stiff black curtain entrance to the darkroom, we stand in dull red light, peering around Bell as he dunks the first of Bainbridge’s experimental photographs in trays of solution. Bainbridge—tall, tanned, whippet-thin and turned out in frayed denim shorts and loose shirt—is here to tinker with potential cover art for his next single.

Pinning down the artist, who’s returned to London after a stay in Berlin, was tricky. _World…_, a jazzy, wistfully soulful electro-funk work recorded in Paris with house maestro Philippe Zdar and released earlier this year to largely favorable acclaim, introduced Bainbridge to an exacting press, and he’s particular now about who he’ll talk to, preferring “intelligent, ethical, political, feminist” leaning publications. His penchant for covering obscure pop songs have been (mis)read by some as ironic homage, while others have taken umbrage at his music videos, seeing a pretentiousness in what he sees as a “childlike” enthusiasm for musical expression. We step out onto the cobbled mews lane to discuss this, taking mugs of hot tea out with us to perch on an adjacent wooden bench, shaded from the occasional patter of summer rain by a sweep of greenery spilling down from a window box above. There is, he says, in a deep, steady and clipped tone, sweeping that long cascade of hazel hair out of his eyes, a “distinct camp of (press) people who find it hard to appreciate innocence in pop music, or are confused that it might even exist.”

Pop, and its sprawling evolution, is of deep interest to Bainbridge. His latest video, for the song “House,” sees the singer in a sharp black suit and tie, sat in front of a retro synthesizer and quoting a Leonard Bernstein monologue from the 1967 CBS special _Inside Pop: The Rock Revolution_. “‘Pop Music is the only form of music that’s been made by, for, and about the kids.’ I looked at that line specifically, because modern pop is still made _for_ a youth audience, but its not really made _by_ that audience, or with their best intentions at heart. Once upon a time it was a platform for youth culture; now it’s just a way to steal their money.” Bainbridge seems genuinely concerned about the current state of pop music. “Its gone to a much darker, exploitative place than it was in Bernstein’s day,” he says, thoughtfully. “Youth culture expresses itself through the internet now; it doesn’t need punk, psychedelic, or disco to express its liberation the way it once did.”

It’s this fascination with the internet’s effect on pop, and the world before it, that’s led Bainbridge to his next project. Instead of hatching album number two (or three, if one counts the 2007 Philadelphia-based artist residency that produced his first, unofficial album, _Live In Philly_), he’s swapping mediums for a spell, and has applied for arts funding to finance a film project he’s been dreaming up. “At Glastonbury festival \[which began in the ’70s\], prior to the internet and mobile phones, teenagers would come, and have too good a time, and then lose their minds and forget where they lived. It turns out there was a chap who’s responsibility was to work out where in England these teenagers may have come from—based on their accent—and then drive them around the country, helping them to find their home.” It’s an eccentric, typically retrospective subject matter, and one that seems entirely fitting for this analogue-loving, romantic sifter of vintage pop annals.

Written by Charlotte Richardson Andrews

Photographed by Franck Sauvaire

I meet Kindness, a.k.a. Adam Bainbridge, at Robin Bell’s photography print studio, an address nestled in a leafy mews behind the bustle and fruit-stacked stalls of West London’s North End Road market. Bell is one of very few professionals still faithfully hand-processing and printing black-and-white photography, a practice that Bainbridge—who used a cadre of analogue synths to make his debut Polydor album, _World, You Need a Change Of Mind_—finds an artistic affinity with. It’s a compact studio, scented with the chemical waft of developer solution, its white washed walls hung with monochrome prints by Richard Avedon and Bill Brandt. Behind the stiff black curtain entrance to the darkroom, we stand in dull red light, peering around Bell as he dunks the first of Bainbridge’s experimental photographs in trays of solution. Bainbridge—tall, tanned, whippet-thin and turned out in frayed denim shorts and loose shirt—is here to tinker with potential cover art for his next single.

Pinning down the artist, who’s returned to London after a stay in Berlin, was tricky. _World…_, a jazzy, wistfully soulful electro-funk work recorded in Paris with house maestro Philippe Zdar and released earlier this year to largely favorable acclaim, introduced Bainbridge to an exacting press, and he’s particular now about who he’ll talk to, preferring “intelligent, ethical, political, feminist” leaning publications. His penchant for covering obscure pop songs have been (mis)read by some as ironic homage, while others have taken umbrage at his music videos, seeing a pretentiousness in what he sees as a “childlike” enthusiasm for musical expression. We step out onto the cobbled mews lane to discuss this, taking mugs of hot tea out with us to perch on an adjacent wooden bench, shaded from the occasional patter of summer rain by a sweep of greenery spilling down from a window box above. There is, he says, in a deep, steady and clipped tone, sweeping that long cascade of hazel hair out of his eyes, a “distinct camp of (press) people who find it hard to appreciate innocence in pop music, or are confused that it might even exist.”

Pop, and its sprawling evolution, is of deep interest to Bainbridge. His latest video, for the song “House,” sees the singer in a sharp black suit and tie, sat in front of a retro synthesizer and quoting a Leonard Bernstein monologue from the 1967 CBS special _Inside Pop: The Rock Revolution_. “‘Pop Music is the only form of music that’s been made by, for, and about the kids.’ I looked at that line specifically, because modern pop is still made _for_ a youth audience, but its not really made _by_ that audience, or with their best intentions at heart. Once upon a time it was a platform for youth culture; now it’s just a way to steal their money.” Bainbridge seems genuinely concerned about the current state of pop music. “Its gone to a much darker, exploitative place than it was in Bernstein’s day,” he says, thoughtfully. “Youth culture expresses itself through the internet now; it doesn’t need punk, psychedelic, or disco to express its liberation the way it once did.”

It’s this fascination with the internet’s effect on pop, and the world before it, that’s led Bainbridge to his next project. Instead of hatching album number two (or three, if one counts the 2007 Philadelphia-based artist residency that produced his first, unofficial album, _Live In Philly_), he’s swapping mediums for a spell, and has applied for arts funding to finance a film project he’s been dreaming up. “At Glastonbury festival \[which began in the ’70s\], prior to the internet and mobile phones, teenagers would come, and have too good a time, and then lose their minds and forget where they lived. It turns out there was a chap who’s responsibility was to work out where in England these teenagers may have come from—based on their accent—and then drive them around the country, helping them to find their home.” It’s an eccentric, typically retrospective subject matter, and one that seems entirely fitting for this analogue-loving, romantic sifter of vintage pop annals.

Written by Charlotte Richardson Andrews

.JPG)

.jpg)