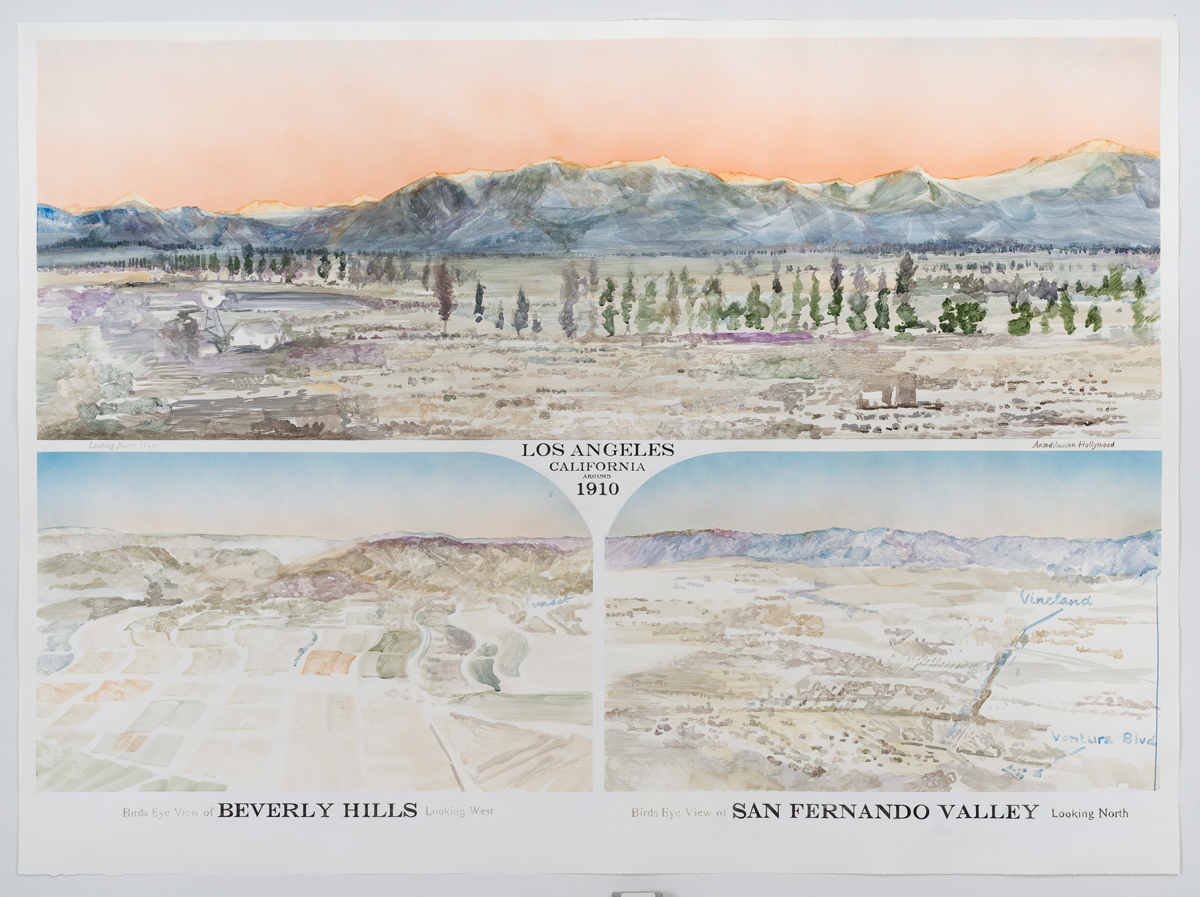

“THREE VIEWS OF LOS ANGELES BEFORE WATER,” (2013). WATERCOLOR, GOUACHE, AND INK ON PAPER IN ARTIST’S FRAME. 68 1/4 X 93 INCHES. COURTESY THE NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM OF L.A. COUNTY. PHOTO: ROBERT WEDEMEYER.

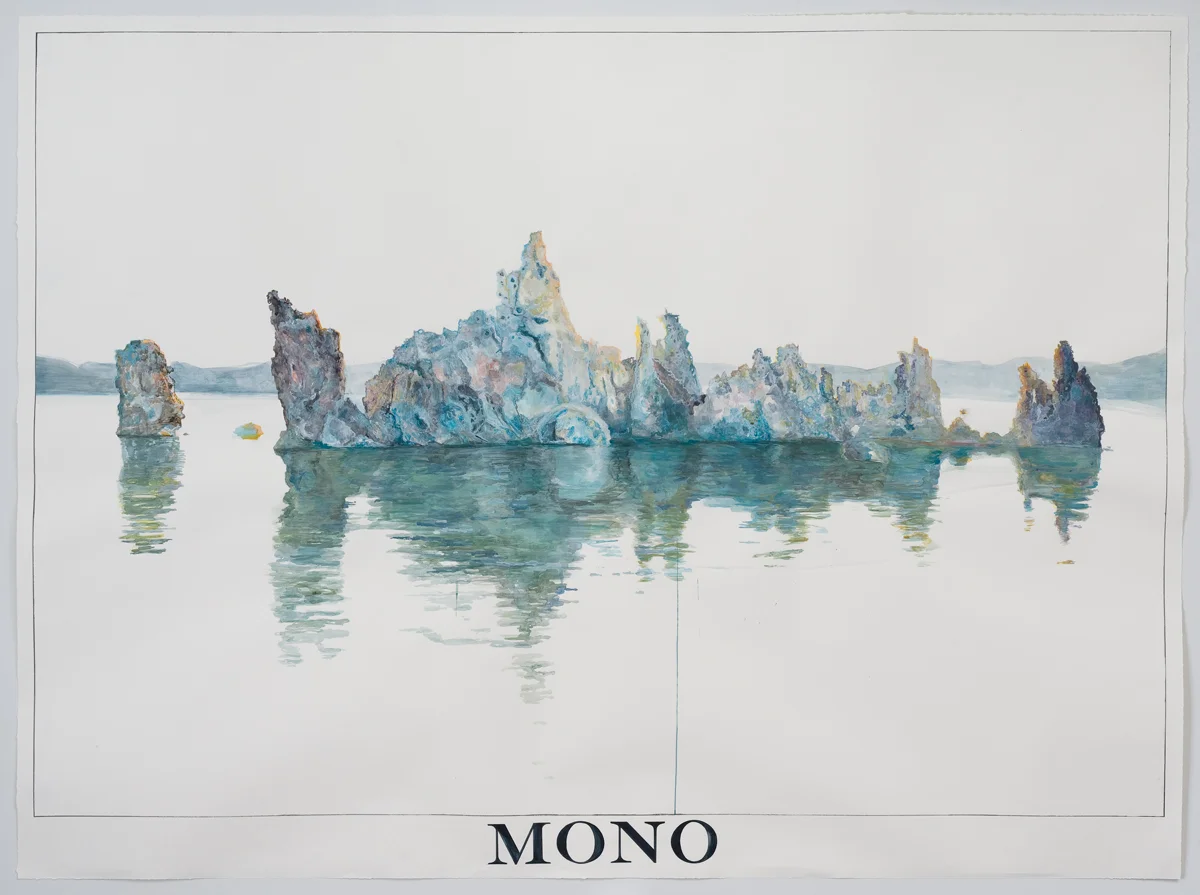

“SOUTH TUFA, MONO LAKE AT 7:12 AM, JUNE 18TH,” (2013). WATERCOLOR AND GOUACHE ON PAPER IN ARTIST’S FRAME. 71 X 96 INCHES. COURTESY THE NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM OF L.A. COUNTY. PHOTO: ROBERT WEDEMEYER.

[](#)[](#)

Rob Reynolds

Designing a Memorial to the Aqueduct’s Building Team That Resonated Within Southern California’s Cultural Milieu

We are in a celebratory mood this issue, and like most periods of mirth and salutation, the moment is fleeting. That sense of impermanent delight is one of the focal points discussed with Los Angeles-based artist Rob Reynolds, whose series of watercolor works on paper and text-printed banners, titled Just Add Water, currently adorns the walls and banisters of the Los Angeles County Natural History Museum’s rotunda, through August 3, 2014. The series premiered on November 5, 2013, in conjunction with the centennials of two cardinal fixtures of L.A. County: the NHMLA itself, and the Los Angeles Aqueduct. Commissioned by guest curator Charlotte Eyerman, Reynolds spent four months researching the aqueduct’s history—both its dominant narrative and yet-undisclosed “secret history”—and the social context of what he likes to call “the arrival of Big Water to Los Angeles,” to produce ten poster-sized watercolors and thirteen banners of text in a provocative site-specific installation that prompts the question: “How long can we live like this?”

According to Reynolds, in many ways this project became an exercise in revisionist history. Textbooks inform us how Big Water came to Los Angeles, but as new evidence and new voices emerge, we gain a different take on those events. Reynolds begins his series, and therefore his account, with a century-old image of the Hollywood Hills looming over the L.A. Basin as it naturally existed back then—a dusty chaparral—reverting the viewer back to the semi-arid ecosystem awaiting a lush garden of Eden makeover once the aqueduct floodgates would open in 1913.

“It’s really a story of a progressivist act of pure will, a colonial project to settle and develop the Los Angeles area specifically, and it’s radically irrational…the promise then was one of limitless resources that enable limitless expansion and limitless consumption.” The man delivering this promise to the masses was one William Mulholland, who epitomized the ideology of progress achieved by advancing technology and, hence, the human condition, with the construction of a $24 million concrete channel to carry billions of gallons of water from the Owens Valley—233 miles south to L.A. There’s plenty of controversy surrounding the team of men Mulholland enlisted to buy rights to the water from the Inyo County locals using Owens Lake for subsistence farming (in _Chinatown_, Roman Polanski’s triumphant neo-noir depiction of intrigue surrounding California’s water wars, screenwriter Robert Towne makes reference to these figures in what he imagined as “The Syndicate”). But what interests Reynolds even more about the aqueduct is the actual men and women that were involved in its construction, a volume of names allegedly several thousand deep, and upon Reynolds’ analysis, not yet consolidated into any official archive.

“I thought it would be as easy as going down to DWP and asking them to point me to the ledgers…I knew the names were out there, I just didn’t know where.” Reynolds eventually unearthed real estate records in the Inyo County Courthouse, boxes of files in the Eastern California Museum, and petitions from the Owens Valley citizenship against Mulholland’s water acquisition. “It ended up being like a core sample you drill down and suck up. You know you didn’t get everyone, but we ended up with about 8,000 names.”

In designing a memorial to the aqueduct’s building team that resonated within Southern California’s cultural milieu, Reynolds drew inspiration from the light and space art movement, particularly the work of Robert Irwin, to create a display of banners using translucent fabric that glow in the rotunda’s ambient light. The names are arranged in non-hierarchical order using an algorithm designed by movie title designer Andy Goldman to align the edge of the text with the contours of the aqueduct’s path from Owens Lake to Los Angeles, underscoring at the correlation between our water supply and human toil. “I’m not pushing it into the frame,” Reynolds says, “but I feel this kind of layering becomes the subconscious of the art installation.”

Reynolds’ approach to the watercolors themselves draws upon an acute selection of motifs that plant the story of Big Water square into the zeitgeist of modern Los Angeles. Citing their dimension and Pop Art realism—a reputable hat-tip to the works of Ed Ruscha—the watercolors resemble posters mounted in front of a movie theater. In one frame, a simple glass of water rests above a Times New Roman text of the iconic quote made by Mulholland at the opening ceremony of the aqueduct in 1913, where he told the assembly before him, “There it is. Take it.” Reynolds says, “I wanted it to look like an Apple Computer ad, so I used that typeface. It also points to this fantasy of absolute mobility and self-empowerment, which is part of the ethos in California—that unvarnished idealism. And it’s just a glass of water.”

Reynolds also points toward how alien L.A.’s water supply truly is, and brings an element of science fiction into the frame. In one compelling juxtaposition, he pairs the barren landscape of nearly depleted Mono Lake—another Owens Valley wellspring funneled into the aqueduct, whose spires of tufa twisting upward from a diminishing pool of salinated brine appear more Martian than Californian—against the retro-futuristic Brutalist beast of steel and glass that is the Department of Water and Power’s headquarters. Side by side, corporate brawn appears to dominate over an endangered natural resource, but in reverse, we’re also reminded of the 1978 environmental movement, when a David of thousands of bumper stickers pleading to “Save Mono Lake” mobilized non-profit organizations and legislators alike to bring the Goliath of the LADWP to its knees.

As an L.A.-based artist, Reynolds acknowledges that he is very much a beneficiary of this cup that overfloweth with creative opportunity and international cultural significance as provided for by what many blindly assume is an unlimited supply of water. Yet here we are in the middle of the greatest drought in California’s recorded history, the consequences of which may likely be horrendous—those same consequences might also generate new artistic expression; the mid-1970s brought severe drought to the Southland and forced residents to empty their swimming pools, inviting the Z-Boys to revolutionize skateboarding forever. “It’s a little bit like blinding yourself to become a great dancer. The most perverse and beautiful aspect of that horrible drought is that now skateboarders dive like Nijinsky dances ballet.”

Who’s to say what beauty may emerge from the impending crisis, but the facts indicate that an era is likely coming to a close, and our eyes will eventually be forced open. Driving over the Cahuenga Pass into the San Fernando Valley, one is lambasted with light and space advertising for the next _Transformers_ installment with such urgency and pomp that any public service campaign to initiate change in the way we wash our cars or water our lawns for the sake of conservation would be crushed beneath a Decepticon’s talon.

Los Angeles is a borrowed city, and the ink on its library card is quickly fading. Meanwhile, Houses of Congress exchange rhetoric over building the Keystone XL Pipeline, posing a devastating threat to the residents living in its vicinity as well as the environment at large. And here at home, the fracking industry has pummeled its way into the heart of the city of Baldwin Hills. These stories are no longer a secret, and although Jake Gittes was famously told to “Forget it” in the closing shot of _Chinatown_, we ought to pay attention to the way artists like Rob Reynolds connect the dots, from Ruscha’s “The Los Angeles County Museum on Fire,” to a steel water pipe hovering above the desert floor bearing a caution sticker. Because, after all, there are no coincidences, Man.