[](#)[](#)

All of My Letters to Home Were Returned to Sender

Literary Turns at Summer Camp

### _The Zip Line_

Written by Blake Kimzey

—

We met at the top of the hill after midnight because Holly wanted to zip line naked. At lunch she asked if I’d join her. It was the end of counselor orientation and campers wouldn’t arrive for two days. We’d spent the week readying Camp Chapawee for opening day.

I snuck through the men’s side of camp and found Holly waiting at the base of the platform.

“What took you so long?” she asked, her frame watermarked against the dark.

“Cabin pillow talk,” I said.

“I hope you weren’t already bragging,” she said. She produced a key from around her neck and unlocked the gate. “I told you I’d get the key.”

I followed her up a switchback of metal steps. On the platform she pulled her t-shirt over her head and stepped from her shorts. She wasn’t wearing a bra or panties. I tried not to stare at the key dangling between her breasts. So I took my clothes off and was self-conscious standing in the cool night air. I held my hands in front of me, the bulk of my watch covering my crotch.

Then Holly handed me a harness.

“Make sure it’s tight around the thighs,” she said, and smiled. “That’ll keep the blood down there.”

The moon broke through a bank of slow moving clouds and Holly’s body shined in the faint light, freckles constellated across her chest. I had noticed her in the dining hall the first night. Red hair and fair skin. We ended up on the same crew the following morning. We cleared the main trail threading through a juniper wood leading to the lakeshore. A multicolored Blob tethered to the end of a large dock bobbed on the water.

By day four Holly’s nose had peeled from sunburn and we found ourselves following each other around between meals and seated close to each other at the nightly campfire tepee talk. And now we were locked in at the top of parallel zip lines, tiptoeing the platform looking out over a darkened canopy of red cedars.

“Race you down,” Holly said. She pushed off and so did I.

The wind pushed between my thighs and the air was fresh against my chest. In front of me Holly’s hair fluttered above her shoulders. I wondered how many times we could do this. But then we quickly got to the bottom and realized we were fucked: we hung just above where the landing platform should have been.

I looked at Holly. She saw panic ghost my face.

“I forgot about the dismount,” she said, and buried her head in her hands. She was laughing. We were stranded thirty feet above ground and stayed quiet for a minute. We would hang there until someone found us.

“One day when people ask how we met you can tell them I got you fired on our first date.”

“And I’ll say it was totally worth it,” I said.

After a while we accepted our fate. Holly pretended to jog in place to make me laugh. We talked and swung toward each other, hooked legs so we could hug for warmth, and kissed until our mouths pressed dry. Sometime before dawn we fell asleep, hunched over the front of our harnesses holding each other.

We were startled awake by mechanical gears bringing the landing platform up. Standing in overalls and work boots by the gearbox with his back to us was Reid, the head maintenance guy. Our clothes gathered at his feet.

“Y’all better get proper before the cooks start breaking eggs,” he said.

“Hey Reid,” I said, because I didn’t know what else to say.

“Hey Reid,” Holly repeated.

“This’ll stay between us,” Reid said, and walked toward the woods and hard-packed trail leading up the hill. I looked at my watch. We were still an hour away from morning wakeup call. We unclipped from the harnesses, showed ourselves to our clothes, to breakfast, and in time, each other.

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487292065461-DJMC1M4PE15TPQN31E1T/fiftholympiadoff00berg-dragged-1.gif)

### _Microphone_

Written by E. S. O. Martin

—

The Scout Master took a shortcut through the woods. He walked in solitude, enjoying the sounds of the birds. There were the “cheeseburger birds,” whose calls sounded like a drive-through order (“Cheeseburger, cheese-cheese-cheeseburger.”) and the laser birds (“Pew-pew-pew!”) and the Twitter birds, whose calls sounded exactly like the notification on his cell phone, causing his hand to flinch toward his pocket only to remember that he’d locked the phone in his truck. He had resolved to not check his phone during his week-long stay at camp, even though he felt naked without it.

Cutting through his peaceful reverie, he heard a loud squawking and fluttering of wings. It was an urgent noise, frightened and full of panic. All the other birds in the forest fell silent. The Scout Master passed a large boulder and saw a Scout jamming a stick into a tree stump, where a bird had built its nest.

“Stop it! What are you doing?” The Scout Master trotted up to the boy.

“There’s a microphone in the stump,” the Scout said, he was nine or ten years old and his face was open and innocent. “It makes noise when you poke a stick in there, see?” The boy jammed the stick into the stump, rattling it around, which resulted in more squawking. Feathers rustled against wood.

The Scout Master snatched the stick away. “What makes more sense, that there’s a microphone in the middle of the woods, or that there’s a bird in there that you’re hurting?”

The boy cocked his head. “There’s a bird in there?”

The Scout Master felt a chill slide down the side of his ribs as he realized that, for this boy, a microphone might actually be as plausible as a bird. The digital world had begun to overlay the physical one like a second skin. There were apps that highlighted the constellations when you pointed your phone at the night sky. The entirety of human wisdom could be accessed from a device small enough to fit around this boy’s wrist…yet the boy didn’t know a birdcall when he heard one.

“Yes,” he said. “There’s a bird in there, and you’re hurting it.”

A look passed over the boy’s face as realization dawned. A first encounter with an alien species, and he caused it harm. The boy’s eyes pinched closed, becoming teary with sincere contrition.

“Run along, now,” the Scout Master said. “It’s time for flags.”

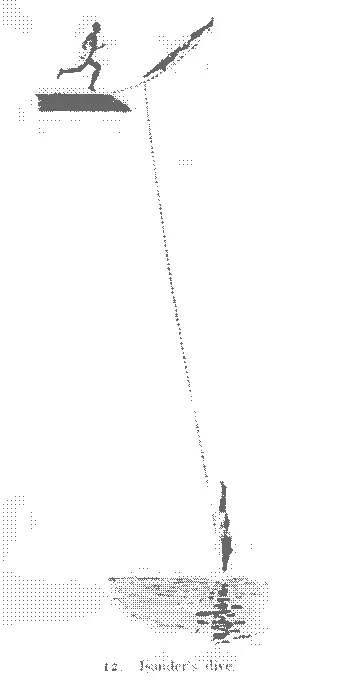

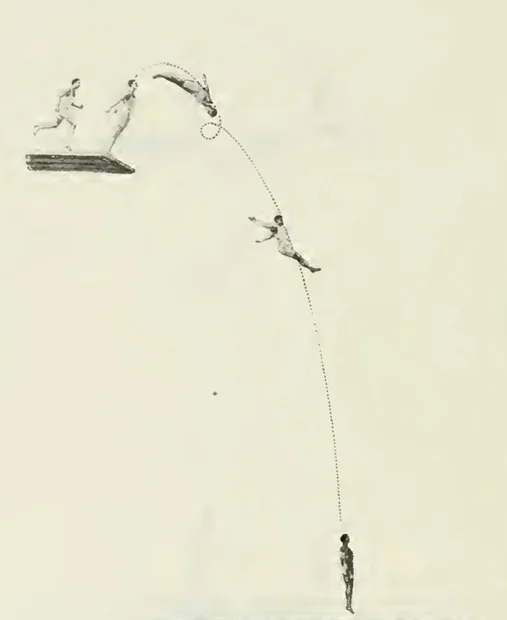

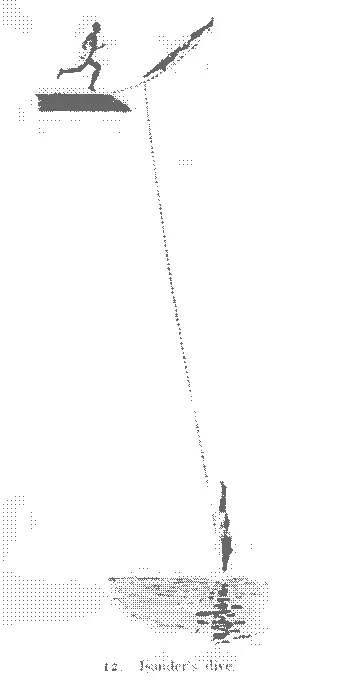

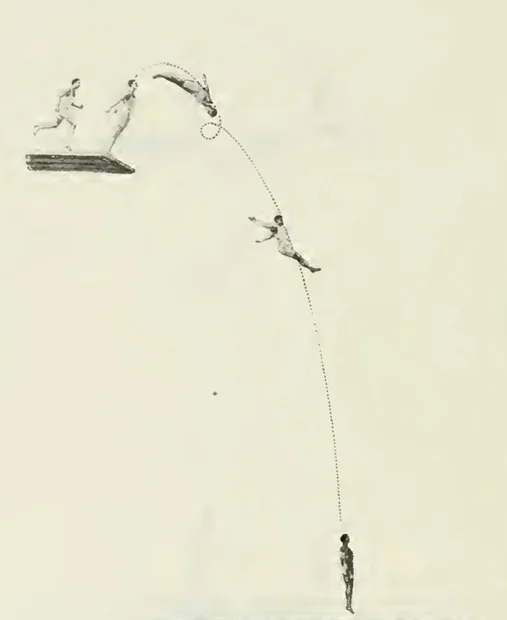

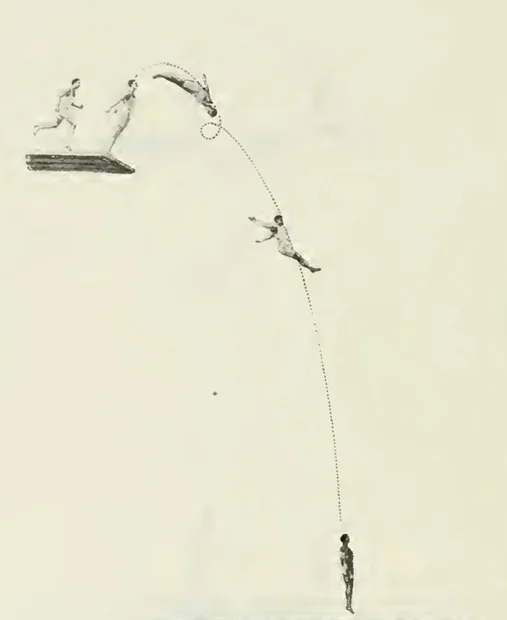

Images from “The fifth Olympiad: the official report of the Olympic Games of Stockholm 1912,” by Erik Bergval. © Wahlstrom & Widstrand, Stockholm, 1913.

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487292067455-8709T1CJ3YGDQG2QP6CQ/fiftholympiadoff00berg-dragged-3-copy.jpg)

### _The Ritual_

Written by Justin Lee

—

It seemed the peephole must always have been there, that even if the girls’ bunkhouse was never built, there would still have been a nickel-sized hole six feet off the ground, a window into another world.

The tradition was so old that it didn’t need to be spoken of. It was to happen on Thursday night, the second-to-last night of camp. All that day an electric anticipation thrummed the air. Then, long past lights-out, we would slip out silently, solemnly and pad along the tree line behind the mess hall to the back of the girls’ bunkhouse.

Surely the counselors knew what was happening, yet never did they intervene. It was as if their negligence, too, was part of the ritual.

We dragged cinder blocks from the woods up to the stone wall and stacked them three high. There was never any jostling for position. We took it turns. We’d finish our go and get back in line.

What we saw differed each year, depending on the girls. Some were brazen, happy to sit topless. But even the most modest showed skin. They sat in a circle around bright candles, perhaps fifteen girls. They played Truth or Dare.

We heard everything. We saw everything. We never spoke of it. We honored the taboo and contented ourselves with memory, the resonance of the forbidden bathed in flickering sepia.

Crispin was new that summer. He was clear-eyed and blond and bound to a motorized wheelchair. He suffered from cerebral palsy. He still retained enough motor skills to engage in many of our activities, and he watched enthusiastically as we played the more athletic games. He was quiet, for speaking was difficult. But he was content, even beatific.

Everyone was taken with him, not out of sympathy, but because we sensed in him an uncanny resiliency, something we could witness and be inspired by, but never possess. The boy glowed.

Thursday night came, and we had all kept our usual silence, but Crispin was unsurprised. It was as if he could read the hum of our anticipation like a musical score. His wheelchair was less adept at moving through grass, and the motor made noise, so we pushed him along with us to the girls’ bunkhouse.

We formed our line at the peephole, and it became apparent that Crispin could not participate. We couldn’t remove him from the chair and lift him without hurting him. So he sat off to the side, watching us watch the girls.

We don’t know when the girl came outside and stood with us, but when we noticed her we went still. She stared placidly at us for a while, then she went to Crispin, kissed him on the forehead, and wheeled him to the side of the building where there was a ramped entrance. Another girl met her at the door and they brought him inside.

For the first time in memory we jostled for position. As soon as one boy had his eye at the hole another pushed him aside and took his place.

All any of us saw were still frames: Crispin at the center of the circle, ringed by candles, his back to us. All the girls naked, their bras and panties pooled on the floor. Each of them kneeling before him, doing something we could not see.

When the gasp came, it gouged the silence like an airbrake dumping pressure. Those of us near the wall discovered something strange. The peephole had vanished. In its place was smooth stone.

We were certain that that the ritual’s enchantment was broken, that Crispin’s cry would draw the counselors. So we fled. Back to the boys’ bunkhouse, back to our beds, where we lay feigning sleep until morning.

When day came, all was as it had always been. The knowing glances. The blushing joy of shared secrets. But there was no Crispin. Not even the counselors seemed to miss him. He had vanished with the peephole. Whatever ritual we’d been enacting, he was its climax and conclusion.

And yet the taboo persists. Our silence holds.

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487292066151-QRXL3B3WVMMHV2RE8WIX/fiftholympiadoff00berg-dragged-2.gif)

### _Sitting_ _Out_

Written by Sarah Sansolo

—

Tonight is the end-of-summer dance, and everyone’s up the hill in the gym except for the girl with the pink hair and one of her boyfriends. They’re down by the boathouse, and a few counselors have gone after them. And then there’s Kristy and I, sitting in the grassy area that separates the girls’ bunks from the boys’, not far from the path where I had my first kiss with Jake last week.

I puckered up the wrong way and it was sloppy and gross, and I’ve been making up excuses not to kiss him ever since.

I know I’m supposed to be dancing with him; that’s why the girls in my bunk insisted on doing my makeup and plucking my eyebrows and dressing me in Beth’s halter top (which you absolutely cannot wear a bra under). And I did dance with him at first, and he told me I looked nice.

But when Kristy left the gym, I followed. It’s the last night, and I don’t want to spend it with anyone else. She’s wearing the same thing she does every day: jeans, sandals, t-shirt, long dark ponytail. I wish I could wear something like that without the girls in my bunk fixing me.

I watch the dance of flashlights on the water and the wood planks of the boathouse, and I wonder aloud why anyone would want to hang out all the way down there.

Kristy’s fifteen and in the bunk with the pink-haired girl, so of course she knows. She leans back on her hands and waits for a long moment. “Blowjobs.”

It takes me a minute to work up the nerve to ask Kristy what “blowjob” means.

She laughs. Not the way the girls in my bunk laugh, as if they think I’m some sort of idiot. Kristy laughs like what I don’t know delights her. “Trust me, you don’t want to think about that.”

I don’t ask again. I don’t even ask why she’s here with me and not down at the boathouse herself, or dancing with some guy in the gym. She doesn’t have a boyfriend, even though she deserves one more than I do. She’s tall and tan and pretty even without makeup, nothing like me. But then I only got Jake because everyone else in our group of friends paired up and we were left.

I know I should feel bad that I ditched Jake at the dance, but I’m happier here in the cool dark with Kristy. She doesn’t care if I look nice or not. She doesn’t even look at me, just down at the dark lake, like she’s memorizing it before we go home tomorrow.

I memorize her instead.

[](#)[](#)

All of My Letters to Home Were Returned to Sender

Literary Turns at Summer Camp

### _The Zip Line_

Written by Blake Kimzey

—

We met at the top of the hill after midnight because Holly wanted to zip line naked. At lunch she asked if I’d join her. It was the end of counselor orientation and campers wouldn’t arrive for two days. We’d spent the week readying Camp Chapawee for opening day.

I snuck through the men’s side of camp and found Holly waiting at the base of the platform.

“What took you so long?” she asked, her frame watermarked against the dark.

“Cabin pillow talk,” I said.

“I hope you weren’t already bragging,” she said. She produced a key from around her neck and unlocked the gate. “I told you I’d get the key.”

I followed her up a switchback of metal steps. On the platform she pulled her t-shirt over her head and stepped from her shorts. She wasn’t wearing a bra or panties. I tried not to stare at the key dangling between her breasts. So I took my clothes off and was self-conscious standing in the cool night air. I held my hands in front of me, the bulk of my watch covering my crotch.

Then Holly handed me a harness.

“Make sure it’s tight around the thighs,” she said, and smiled. “That’ll keep the blood down there.”

The moon broke through a bank of slow moving clouds and Holly’s body shined in the faint light, freckles constellated across her chest. I had noticed her in the dining hall the first night. Red hair and fair skin. We ended up on the same crew the following morning. We cleared the main trail threading through a juniper wood leading to the lakeshore. A multicolored Blob tethered to the end of a large dock bobbed on the water.

By day four Holly’s nose had peeled from sunburn and we found ourselves following each other around between meals and seated close to each other at the nightly campfire tepee talk. And now we were locked in at the top of parallel zip lines, tiptoeing the platform looking out over a darkened canopy of red cedars.

“Race you down,” Holly said. She pushed off and so did I.

The wind pushed between my thighs and the air was fresh against my chest. In front of me Holly’s hair fluttered above her shoulders. I wondered how many times we could do this. But then we quickly got to the bottom and realized we were fucked: we hung just above where the landing platform should have been.

I looked at Holly. She saw panic ghost my face.

“I forgot about the dismount,” she said, and buried her head in her hands. She was laughing. We were stranded thirty feet above ground and stayed quiet for a minute. We would hang there until someone found us.

“One day when people ask how we met you can tell them I got you fired on our first date.”

“And I’ll say it was totally worth it,” I said.

After a while we accepted our fate. Holly pretended to jog in place to make me laugh. We talked and swung toward each other, hooked legs so we could hug for warmth, and kissed until our mouths pressed dry. Sometime before dawn we fell asleep, hunched over the front of our harnesses holding each other.

We were startled awake by mechanical gears bringing the landing platform up. Standing in overalls and work boots by the gearbox with his back to us was Reid, the head maintenance guy. Our clothes gathered at his feet.

“Y’all better get proper before the cooks start breaking eggs,” he said.

“Hey Reid,” I said, because I didn’t know what else to say.

“Hey Reid,” Holly repeated.

“This’ll stay between us,” Reid said, and walked toward the woods and hard-packed trail leading up the hill. I looked at my watch. We were still an hour away from morning wakeup call. We unclipped from the harnesses, showed ourselves to our clothes, to breakfast, and in time, each other.

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487292065461-DJMC1M4PE15TPQN31E1T/fiftholympiadoff00berg-dragged-1.gif)

### _Microphone_

Written by E. S. O. Martin

—

The Scout Master took a shortcut through the woods. He walked in solitude, enjoying the sounds of the birds. There were the “cheeseburger birds,” whose calls sounded like a drive-through order (“Cheeseburger, cheese-cheese-cheeseburger.”) and the laser birds (“Pew-pew-pew!”) and the Twitter birds, whose calls sounded exactly like the notification on his cell phone, causing his hand to flinch toward his pocket only to remember that he’d locked the phone in his truck. He had resolved to not check his phone during his week-long stay at camp, even though he felt naked without it.

Cutting through his peaceful reverie, he heard a loud squawking and fluttering of wings. It was an urgent noise, frightened and full of panic. All the other birds in the forest fell silent. The Scout Master passed a large boulder and saw a Scout jamming a stick into a tree stump, where a bird had built its nest.

“Stop it! What are you doing?” The Scout Master trotted up to the boy.

“There’s a microphone in the stump,” the Scout said, he was nine or ten years old and his face was open and innocent. “It makes noise when you poke a stick in there, see?” The boy jammed the stick into the stump, rattling it around, which resulted in more squawking. Feathers rustled against wood.

The Scout Master snatched the stick away. “What makes more sense, that there’s a microphone in the middle of the woods, or that there’s a bird in there that you’re hurting?”

The boy cocked his head. “There’s a bird in there?”

The Scout Master felt a chill slide down the side of his ribs as he realized that, for this boy, a microphone might actually be as plausible as a bird. The digital world had begun to overlay the physical one like a second skin. There were apps that highlighted the constellations when you pointed your phone at the night sky. The entirety of human wisdom could be accessed from a device small enough to fit around this boy’s wrist…yet the boy didn’t know a birdcall when he heard one.

“Yes,” he said. “There’s a bird in there, and you’re hurting it.”

A look passed over the boy’s face as realization dawned. A first encounter with an alien species, and he caused it harm. The boy’s eyes pinched closed, becoming teary with sincere contrition.

“Run along, now,” the Scout Master said. “It’s time for flags.”

Images from “The fifth Olympiad: the official report of the Olympic Games of Stockholm 1912,” by Erik Bergval. © Wahlstrom & Widstrand, Stockholm, 1913.

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487292067455-8709T1CJ3YGDQG2QP6CQ/fiftholympiadoff00berg-dragged-3-copy.jpg)

### _The Ritual_

Written by Justin Lee

—

It seemed the peephole must always have been there, that even if the girls’ bunkhouse was never built, there would still have been a nickel-sized hole six feet off the ground, a window into another world.

The tradition was so old that it didn’t need to be spoken of. It was to happen on Thursday night, the second-to-last night of camp. All that day an electric anticipation thrummed the air. Then, long past lights-out, we would slip out silently, solemnly and pad along the tree line behind the mess hall to the back of the girls’ bunkhouse.

Surely the counselors knew what was happening, yet never did they intervene. It was as if their negligence, too, was part of the ritual.

We dragged cinder blocks from the woods up to the stone wall and stacked them three high. There was never any jostling for position. We took it turns. We’d finish our go and get back in line.

What we saw differed each year, depending on the girls. Some were brazen, happy to sit topless. But even the most modest showed skin. They sat in a circle around bright candles, perhaps fifteen girls. They played Truth or Dare.

We heard everything. We saw everything. We never spoke of it. We honored the taboo and contented ourselves with memory, the resonance of the forbidden bathed in flickering sepia.

Crispin was new that summer. He was clear-eyed and blond and bound to a motorized wheelchair. He suffered from cerebral palsy. He still retained enough motor skills to engage in many of our activities, and he watched enthusiastically as we played the more athletic games. He was quiet, for speaking was difficult. But he was content, even beatific.

Everyone was taken with him, not out of sympathy, but because we sensed in him an uncanny resiliency, something we could witness and be inspired by, but never possess. The boy glowed.

Thursday night came, and we had all kept our usual silence, but Crispin was unsurprised. It was as if he could read the hum of our anticipation like a musical score. His wheelchair was less adept at moving through grass, and the motor made noise, so we pushed him along with us to the girls’ bunkhouse.

We formed our line at the peephole, and it became apparent that Crispin could not participate. We couldn’t remove him from the chair and lift him without hurting him. So he sat off to the side, watching us watch the girls.

We don’t know when the girl came outside and stood with us, but when we noticed her we went still. She stared placidly at us for a while, then she went to Crispin, kissed him on the forehead, and wheeled him to the side of the building where there was a ramped entrance. Another girl met her at the door and they brought him inside.

For the first time in memory we jostled for position. As soon as one boy had his eye at the hole another pushed him aside and took his place.

All any of us saw were still frames: Crispin at the center of the circle, ringed by candles, his back to us. All the girls naked, their bras and panties pooled on the floor. Each of them kneeling before him, doing something we could not see.

When the gasp came, it gouged the silence like an airbrake dumping pressure. Those of us near the wall discovered something strange. The peephole had vanished. In its place was smooth stone.

We were certain that that the ritual’s enchantment was broken, that Crispin’s cry would draw the counselors. So we fled. Back to the boys’ bunkhouse, back to our beds, where we lay feigning sleep until morning.

When day came, all was as it had always been. The knowing glances. The blushing joy of shared secrets. But there was no Crispin. Not even the counselors seemed to miss him. He had vanished with the peephole. Whatever ritual we’d been enacting, he was its climax and conclusion.

And yet the taboo persists. Our silence holds.

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487292066151-QRXL3B3WVMMHV2RE8WIX/fiftholympiadoff00berg-dragged-2.gif)

### _Sitting_ _Out_

Written by Sarah Sansolo

—

Tonight is the end-of-summer dance, and everyone’s up the hill in the gym except for the girl with the pink hair and one of her boyfriends. They’re down by the boathouse, and a few counselors have gone after them. And then there’s Kristy and I, sitting in the grassy area that separates the girls’ bunks from the boys’, not far from the path where I had my first kiss with Jake last week.

I puckered up the wrong way and it was sloppy and gross, and I’ve been making up excuses not to kiss him ever since.

I know I’m supposed to be dancing with him; that’s why the girls in my bunk insisted on doing my makeup and plucking my eyebrows and dressing me in Beth’s halter top (which you absolutely cannot wear a bra under). And I did dance with him at first, and he told me I looked nice.

But when Kristy left the gym, I followed. It’s the last night, and I don’t want to spend it with anyone else. She’s wearing the same thing she does every day: jeans, sandals, t-shirt, long dark ponytail. I wish I could wear something like that without the girls in my bunk fixing me.

I watch the dance of flashlights on the water and the wood planks of the boathouse, and I wonder aloud why anyone would want to hang out all the way down there.

Kristy’s fifteen and in the bunk with the pink-haired girl, so of course she knows. She leans back on her hands and waits for a long moment. “Blowjobs.”

It takes me a minute to work up the nerve to ask Kristy what “blowjob” means.

She laughs. Not the way the girls in my bunk laugh, as if they think I’m some sort of idiot. Kristy laughs like what I don’t know delights her. “Trust me, you don’t want to think about that.”

I don’t ask again. I don’t even ask why she’s here with me and not down at the boathouse herself, or dancing with some guy in the gym. She doesn’t have a boyfriend, even though she deserves one more than I do. She’s tall and tan and pretty even without makeup, nothing like me. But then I only got Jake because everyone else in our group of friends paired up and we were left.

I know I should feel bad that I ditched Jake at the dance, but I’m happier here in the cool dark with Kristy. She doesn’t care if I look nice or not. She doesn’t even look at me, just down at the dark lake, like she’s memorizing it before we go home tomorrow.

I memorize her instead.

[](#)[](#)

All of My Letters to Home Were Returned to Sender

Literary Turns at Summer Camp

### _The Zip Line_

Written by Blake Kimzey

—

We met at the top of the hill after midnight because Holly wanted to zip line naked. At lunch she asked if I’d join her. It was the end of counselor orientation and campers wouldn’t arrive for two days. We’d spent the week readying Camp Chapawee for opening day.

I snuck through the men’s side of camp and found Holly waiting at the base of the platform.

“What took you so long?” she asked, her frame watermarked against the dark.

“Cabin pillow talk,” I said.

“I hope you weren’t already bragging,” she said. She produced a key from around her neck and unlocked the gate. “I told you I’d get the key.”

I followed her up a switchback of metal steps. On the platform she pulled her t-shirt over her head and stepped from her shorts. She wasn’t wearing a bra or panties. I tried not to stare at the key dangling between her breasts. So I took my clothes off and was self-conscious standing in the cool night air. I held my hands in front of me, the bulk of my watch covering my crotch.

Then Holly handed me a harness.

“Make sure it’s tight around the thighs,” she said, and smiled. “That’ll keep the blood down there.”

The moon broke through a bank of slow moving clouds and Holly’s body shined in the faint light, freckles constellated across her chest. I had noticed her in the dining hall the first night. Red hair and fair skin. We ended up on the same crew the following morning. We cleared the main trail threading through a juniper wood leading to the lakeshore. A multicolored Blob tethered to the end of a large dock bobbed on the water.

By day four Holly’s nose had peeled from sunburn and we found ourselves following each other around between meals and seated close to each other at the nightly campfire tepee talk. And now we were locked in at the top of parallel zip lines, tiptoeing the platform looking out over a darkened canopy of red cedars.

“Race you down,” Holly said. She pushed off and so did I.

The wind pushed between my thighs and the air was fresh against my chest. In front of me Holly’s hair fluttered above her shoulders. I wondered how many times we could do this. But then we quickly got to the bottom and realized we were fucked: we hung just above where the landing platform should have been.

I looked at Holly. She saw panic ghost my face.

“I forgot about the dismount,” she said, and buried her head in her hands. She was laughing. We were stranded thirty feet above ground and stayed quiet for a minute. We would hang there until someone found us.

“One day when people ask how we met you can tell them I got you fired on our first date.”

“And I’ll say it was totally worth it,” I said.

After a while we accepted our fate. Holly pretended to jog in place to make me laugh. We talked and swung toward each other, hooked legs so we could hug for warmth, and kissed until our mouths pressed dry. Sometime before dawn we fell asleep, hunched over the front of our harnesses holding each other.

We were startled awake by mechanical gears bringing the landing platform up. Standing in overalls and work boots by the gearbox with his back to us was Reid, the head maintenance guy. Our clothes gathered at his feet.

“Y’all better get proper before the cooks start breaking eggs,” he said.

“Hey Reid,” I said, because I didn’t know what else to say.

“Hey Reid,” Holly repeated.

“This’ll stay between us,” Reid said, and walked toward the woods and hard-packed trail leading up the hill. I looked at my watch. We were still an hour away from morning wakeup call. We unclipped from the harnesses, showed ourselves to our clothes, to breakfast, and in time, each other.

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487292065461-DJMC1M4PE15TPQN31E1T/fiftholympiadoff00berg-dragged-1.gif)

### _Microphone_

Written by E. S. O. Martin

—

The Scout Master took a shortcut through the woods. He walked in solitude, enjoying the sounds of the birds. There were the “cheeseburger birds,” whose calls sounded like a drive-through order (“Cheeseburger, cheese-cheese-cheeseburger.”) and the laser birds (“Pew-pew-pew!”) and the Twitter birds, whose calls sounded exactly like the notification on his cell phone, causing his hand to flinch toward his pocket only to remember that he’d locked the phone in his truck. He had resolved to not check his phone during his week-long stay at camp, even though he felt naked without it.

Cutting through his peaceful reverie, he heard a loud squawking and fluttering of wings. It was an urgent noise, frightened and full of panic. All the other birds in the forest fell silent. The Scout Master passed a large boulder and saw a Scout jamming a stick into a tree stump, where a bird had built its nest.

“Stop it! What are you doing?” The Scout Master trotted up to the boy.

“There’s a microphone in the stump,” the Scout said, he was nine or ten years old and his face was open and innocent. “It makes noise when you poke a stick in there, see?” The boy jammed the stick into the stump, rattling it around, which resulted in more squawking. Feathers rustled against wood.

The Scout Master snatched the stick away. “What makes more sense, that there’s a microphone in the middle of the woods, or that there’s a bird in there that you’re hurting?”

The boy cocked his head. “There’s a bird in there?”

The Scout Master felt a chill slide down the side of his ribs as he realized that, for this boy, a microphone might actually be as plausible as a bird. The digital world had begun to overlay the physical one like a second skin. There were apps that highlighted the constellations when you pointed your phone at the night sky. The entirety of human wisdom could be accessed from a device small enough to fit around this boy’s wrist…yet the boy didn’t know a birdcall when he heard one.

“Yes,” he said. “There’s a bird in there, and you’re hurting it.”

A look passed over the boy’s face as realization dawned. A first encounter with an alien species, and he caused it harm. The boy’s eyes pinched closed, becoming teary with sincere contrition.

“Run along, now,” the Scout Master said. “It’s time for flags.”

Images from “The fifth Olympiad: the official report of the Olympic Games of Stockholm 1912,” by Erik Bergval. © Wahlstrom & Widstrand, Stockholm, 1913.

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487292067455-8709T1CJ3YGDQG2QP6CQ/fiftholympiadoff00berg-dragged-3-copy.jpg)

### _The Ritual_

Written by Justin Lee

—

It seemed the peephole must always have been there, that even if the girls’ bunkhouse was never built, there would still have been a nickel-sized hole six feet off the ground, a window into another world.

The tradition was so old that it didn’t need to be spoken of. It was to happen on Thursday night, the second-to-last night of camp. All that day an electric anticipation thrummed the air. Then, long past lights-out, we would slip out silently, solemnly and pad along the tree line behind the mess hall to the back of the girls’ bunkhouse.

Surely the counselors knew what was happening, yet never did they intervene. It was as if their negligence, too, was part of the ritual.

We dragged cinder blocks from the woods up to the stone wall and stacked them three high. There was never any jostling for position. We took it turns. We’d finish our go and get back in line.

What we saw differed each year, depending on the girls. Some were brazen, happy to sit topless. But even the most modest showed skin. They sat in a circle around bright candles, perhaps fifteen girls. They played Truth or Dare.

We heard everything. We saw everything. We never spoke of it. We honored the taboo and contented ourselves with memory, the resonance of the forbidden bathed in flickering sepia.

Crispin was new that summer. He was clear-eyed and blond and bound to a motorized wheelchair. He suffered from cerebral palsy. He still retained enough motor skills to engage in many of our activities, and he watched enthusiastically as we played the more athletic games. He was quiet, for speaking was difficult. But he was content, even beatific.

Everyone was taken with him, not out of sympathy, but because we sensed in him an uncanny resiliency, something we could witness and be inspired by, but never possess. The boy glowed.

Thursday night came, and we had all kept our usual silence, but Crispin was unsurprised. It was as if he could read the hum of our anticipation like a musical score. His wheelchair was less adept at moving through grass, and the motor made noise, so we pushed him along with us to the girls’ bunkhouse.

We formed our line at the peephole, and it became apparent that Crispin could not participate. We couldn’t remove him from the chair and lift him without hurting him. So he sat off to the side, watching us watch the girls.

We don’t know when the girl came outside and stood with us, but when we noticed her we went still. She stared placidly at us for a while, then she went to Crispin, kissed him on the forehead, and wheeled him to the side of the building where there was a ramped entrance. Another girl met her at the door and they brought him inside.

For the first time in memory we jostled for position. As soon as one boy had his eye at the hole another pushed him aside and took his place.

All any of us saw were still frames: Crispin at the center of the circle, ringed by candles, his back to us. All the girls naked, their bras and panties pooled on the floor. Each of them kneeling before him, doing something we could not see.

When the gasp came, it gouged the silence like an airbrake dumping pressure. Those of us near the wall discovered something strange. The peephole had vanished. In its place was smooth stone.

We were certain that that the ritual’s enchantment was broken, that Crispin’s cry would draw the counselors. So we fled. Back to the boys’ bunkhouse, back to our beds, where we lay feigning sleep until morning.

When day came, all was as it had always been. The knowing glances. The blushing joy of shared secrets. But there was no Crispin. Not even the counselors seemed to miss him. He had vanished with the peephole. Whatever ritual we’d been enacting, he was its climax and conclusion.

And yet the taboo persists. Our silence holds.

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487292066151-QRXL3B3WVMMHV2RE8WIX/fiftholympiadoff00berg-dragged-2.gif)

### _Sitting_ _Out_

Written by Sarah Sansolo

—

Tonight is the end-of-summer dance, and everyone’s up the hill in the gym except for the girl with the pink hair and one of her boyfriends. They’re down by the boathouse, and a few counselors have gone after them. And then there’s Kristy and I, sitting in the grassy area that separates the girls’ bunks from the boys’, not far from the path where I had my first kiss with Jake last week.

I puckered up the wrong way and it was sloppy and gross, and I’ve been making up excuses not to kiss him ever since.

I know I’m supposed to be dancing with him; that’s why the girls in my bunk insisted on doing my makeup and plucking my eyebrows and dressing me in Beth’s halter top (which you absolutely cannot wear a bra under). And I did dance with him at first, and he told me I looked nice.

But when Kristy left the gym, I followed. It’s the last night, and I don’t want to spend it with anyone else. She’s wearing the same thing she does every day: jeans, sandals, t-shirt, long dark ponytail. I wish I could wear something like that without the girls in my bunk fixing me.

I watch the dance of flashlights on the water and the wood planks of the boathouse, and I wonder aloud why anyone would want to hang out all the way down there.

Kristy’s fifteen and in the bunk with the pink-haired girl, so of course she knows. She leans back on her hands and waits for a long moment. “Blowjobs.”

It takes me a minute to work up the nerve to ask Kristy what “blowjob” means.

She laughs. Not the way the girls in my bunk laugh, as if they think I’m some sort of idiot. Kristy laughs like what I don’t know delights her. “Trust me, you don’t want to think about that.”

I don’t ask again. I don’t even ask why she’s here with me and not down at the boathouse herself, or dancing with some guy in the gym. She doesn’t have a boyfriend, even though she deserves one more than I do. She’s tall and tan and pretty even without makeup, nothing like me. But then I only got Jake because everyone else in our group of friends paired up and we were left.

I know I should feel bad that I ditched Jake at the dance, but I’m happier here in the cool dark with Kristy. She doesn’t care if I look nice or not. She doesn’t even look at me, just down at the dark lake, like she’s memorizing it before we go home tomorrow.

I memorize her instead.

.jpg)