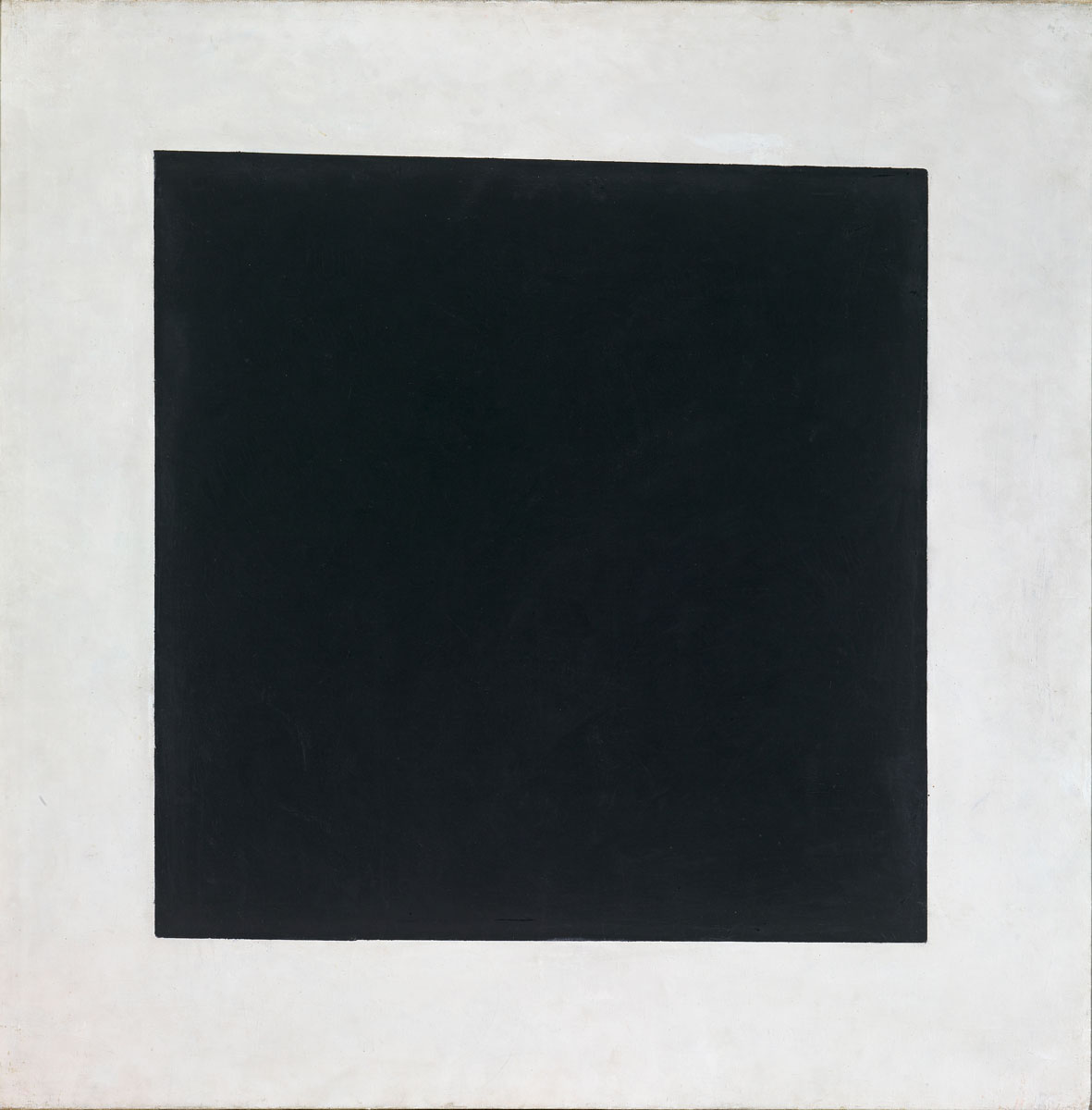

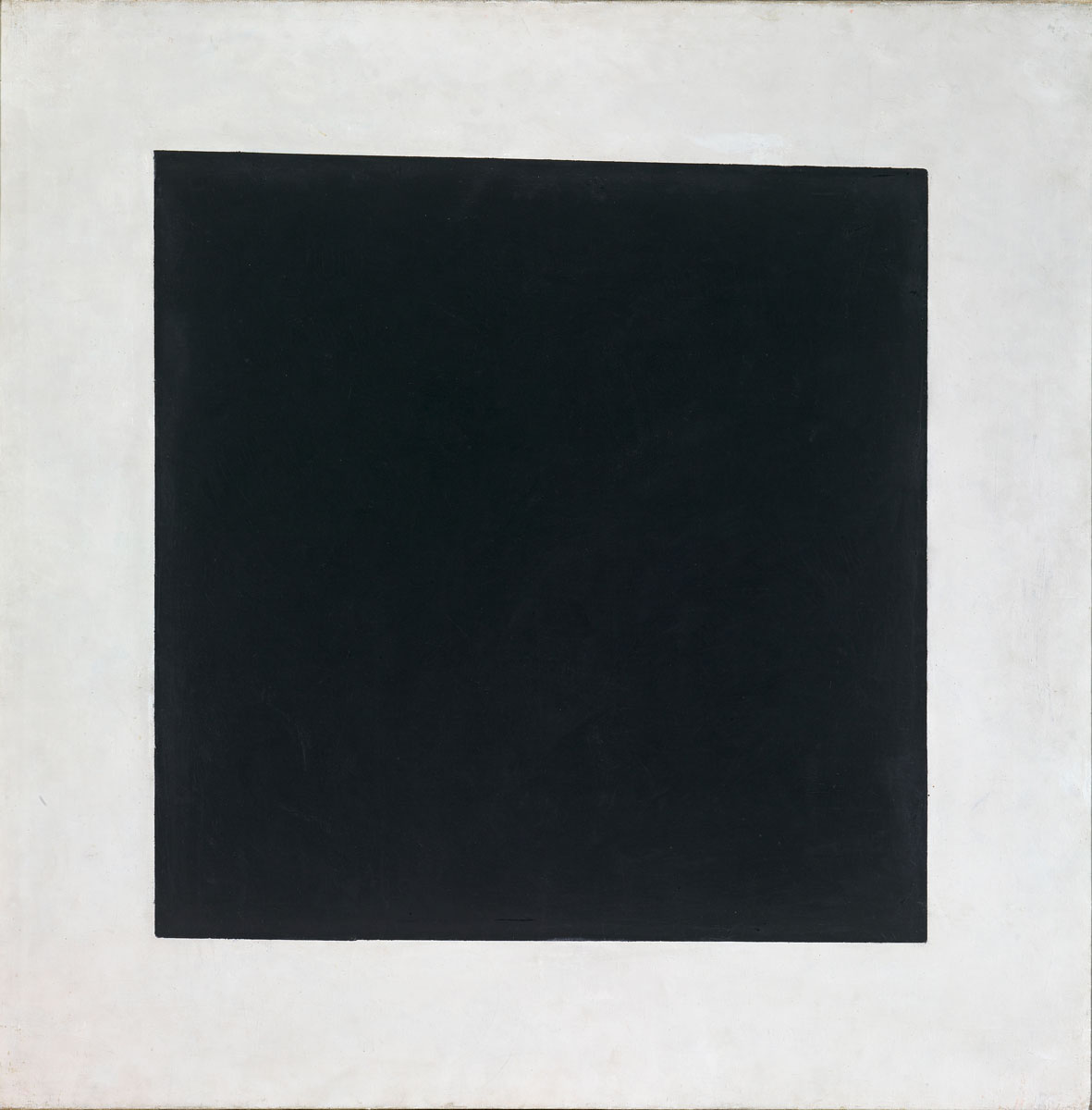

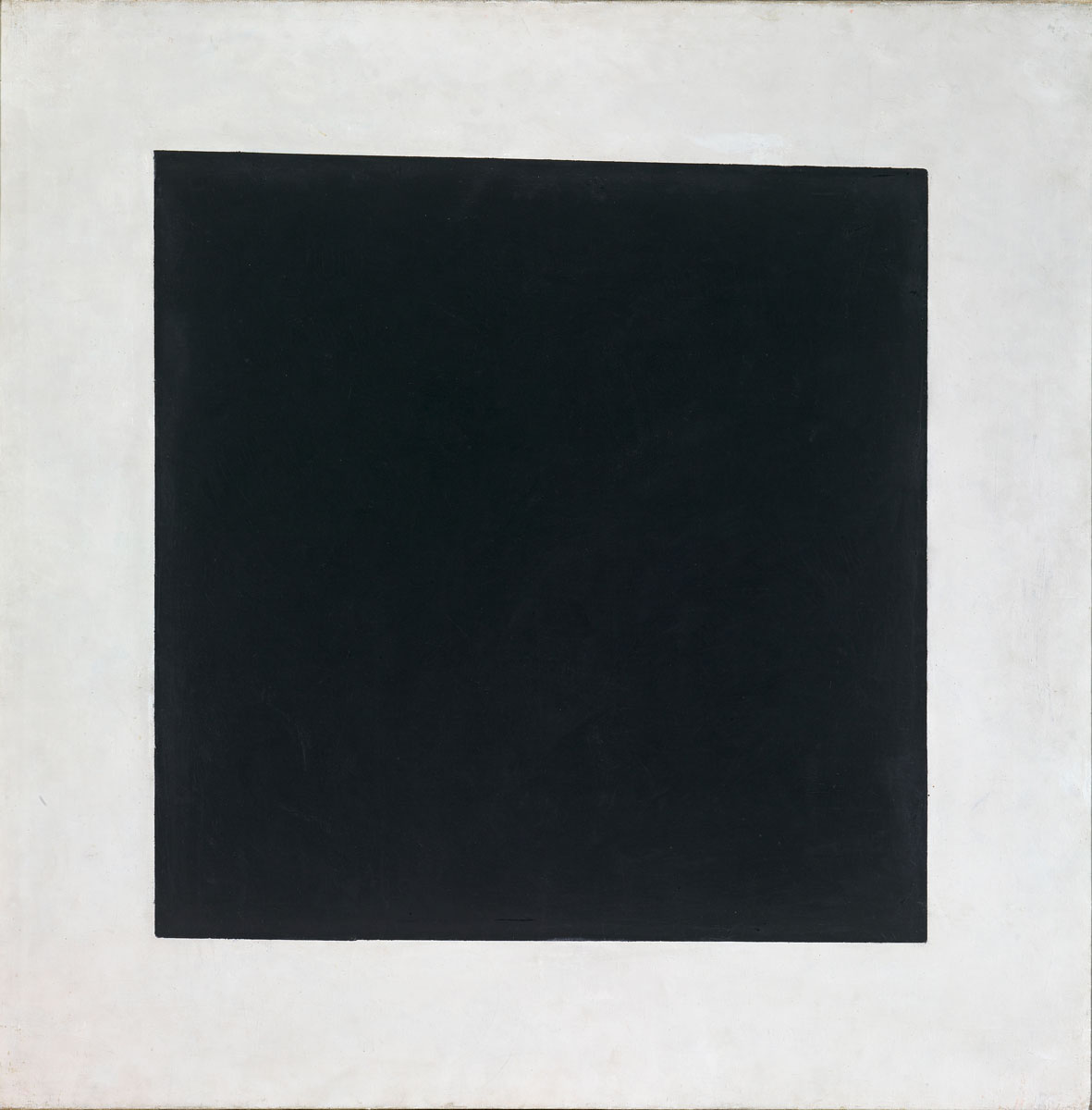

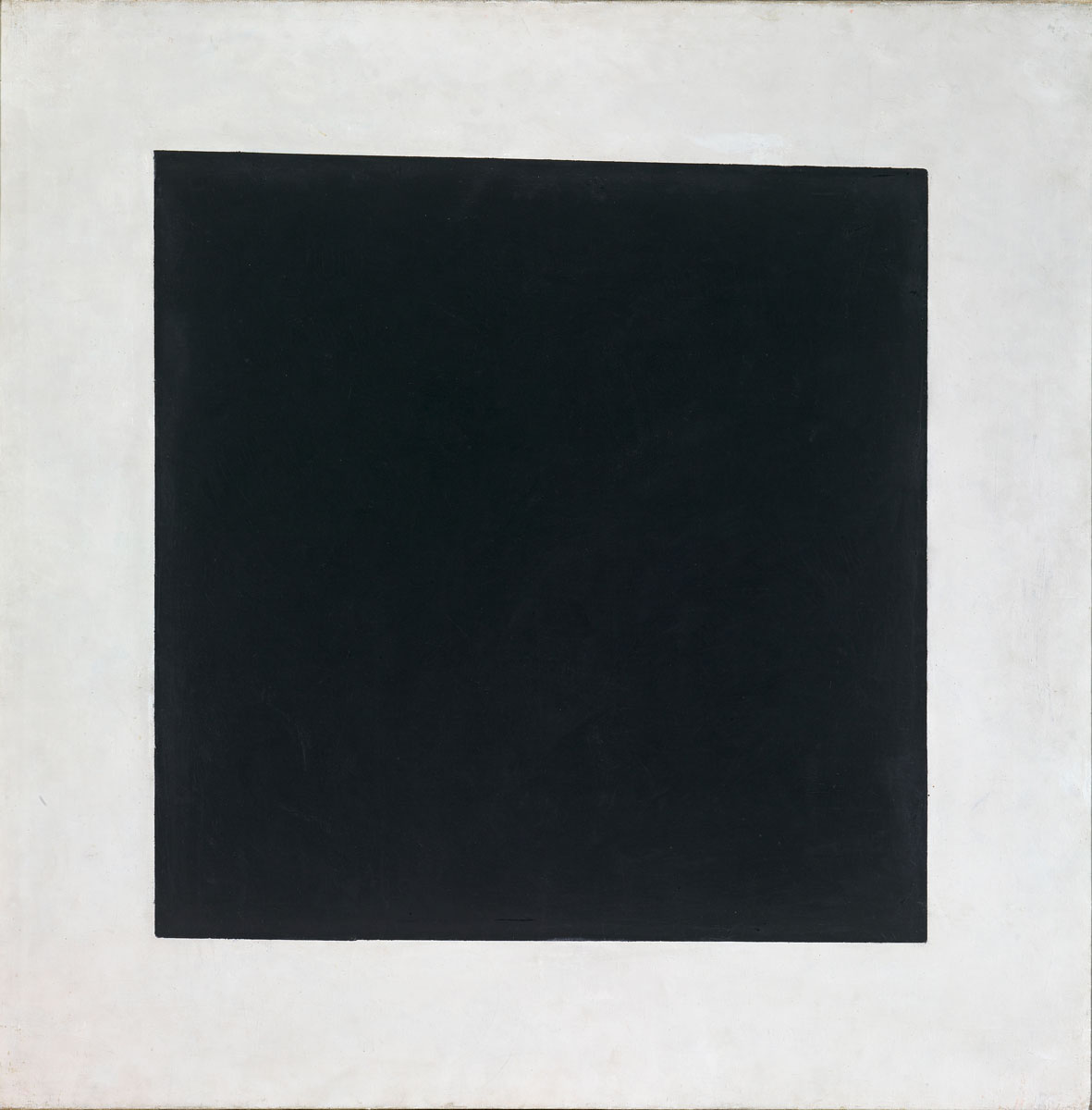

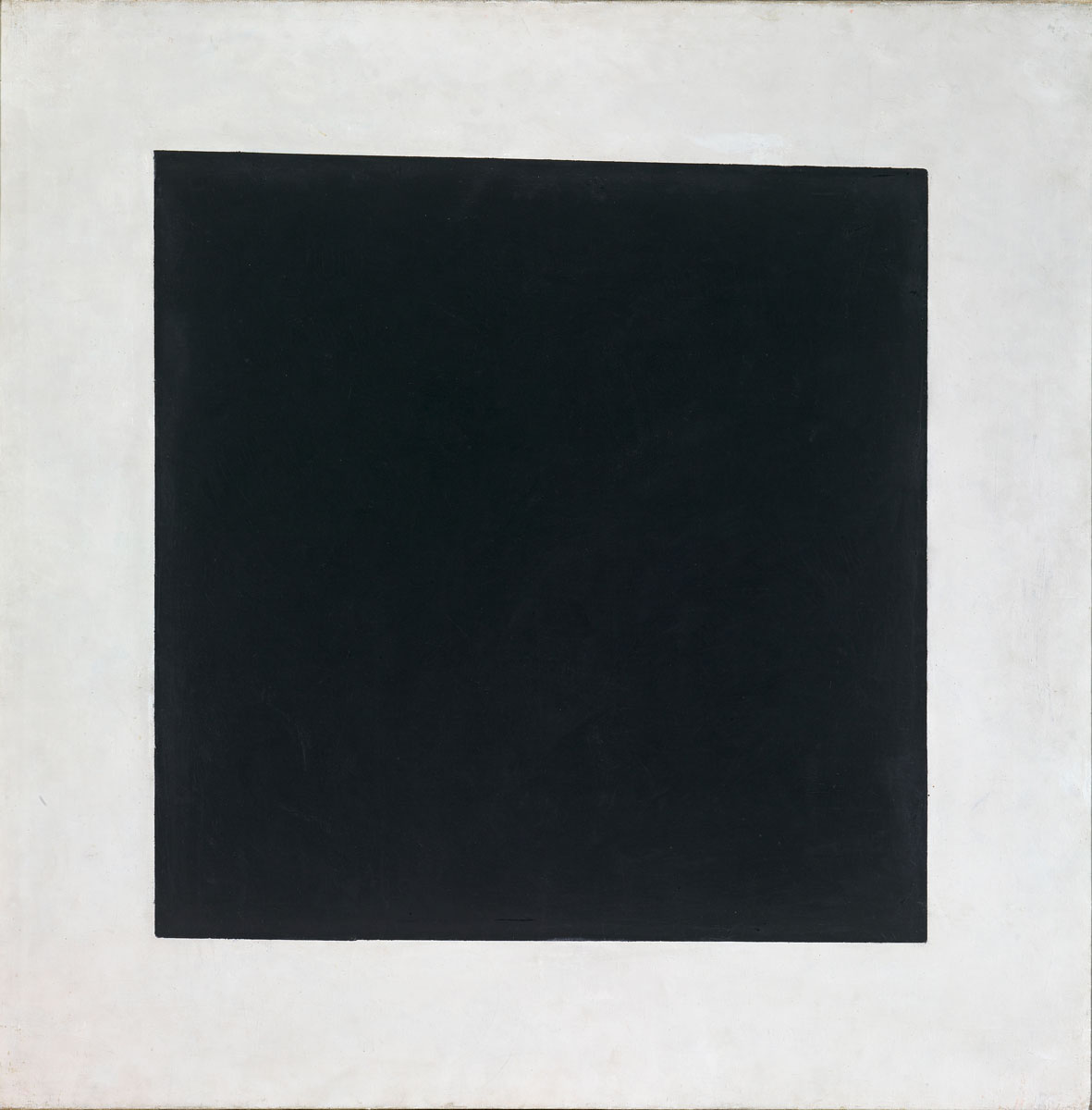

Kazimir Malevich. “Black Square,” (1929). Oil on canvas. 31 x 31 inches. Courtesy The State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

Lyubov Popova. “Painterly Architectonics,” (1918-1976). Oil on canvas. 29 x 19 inches. Courtesy The Greek State Museum of Contemporary Art, Costakis Collection, Thessaloniki.

Gustav Klutsis. “Design for Loudspeaker No. 7,” (1922). Work on paper. 18 x 12 x 1 inches. Courtesy The Greek State Museum of Contemporary Art, Costakis Collection, Thessaloniki.

Mikhail Matyushin. “Landscape,” (1920). Oil on canvas on wood. 15 x 25 inches. Courtesy The Stedelijk Museum Khardzhiev-Chaga, Amsterdam.

Vladimir Tatlin. “Courtier Costume Design For The Theatre Play Tsar Maksemyan,” (1911). Watercolor On Paper. 24 X 18 X 1 Inches. Courtesy The Stedelijk Museum Khardzhiev-Chaga, Amsterdam.

Aleksei Alekseevich Morgunov. “Cubofuturist Composition,” (1915). Work on paper. 34 x 24 inches. Courtesy The Stedelijk Museum Khardzhiev-Chaga, Amsterdam.

Kazimir Malevich. “Self-Portrait,” (1908-1910). Watercolor and gouache on paper. 11 x 11 inches. Courtesy The State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

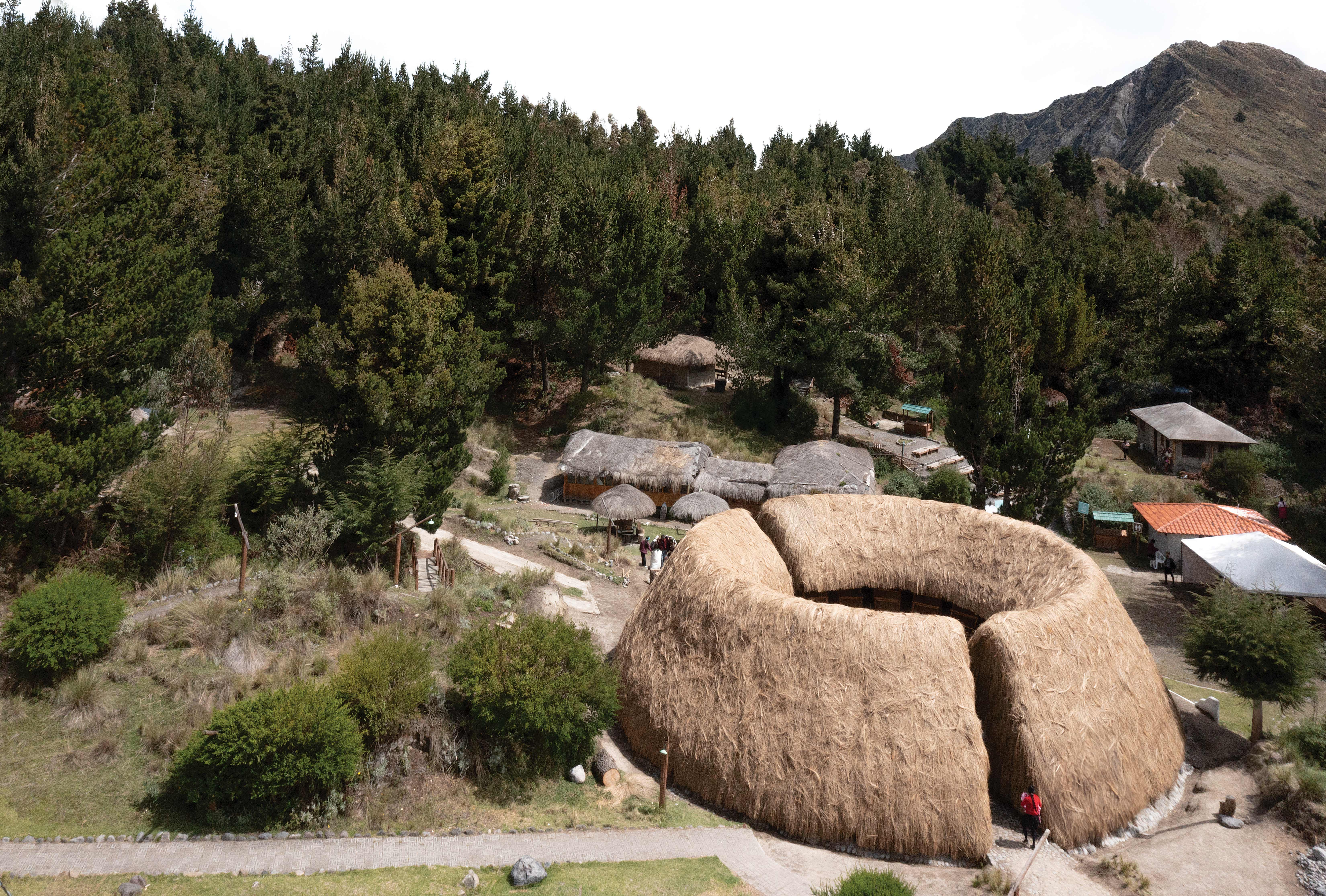

The Sovietsky Hotel Photographed On August 21, 2013 By Omri Cohen.

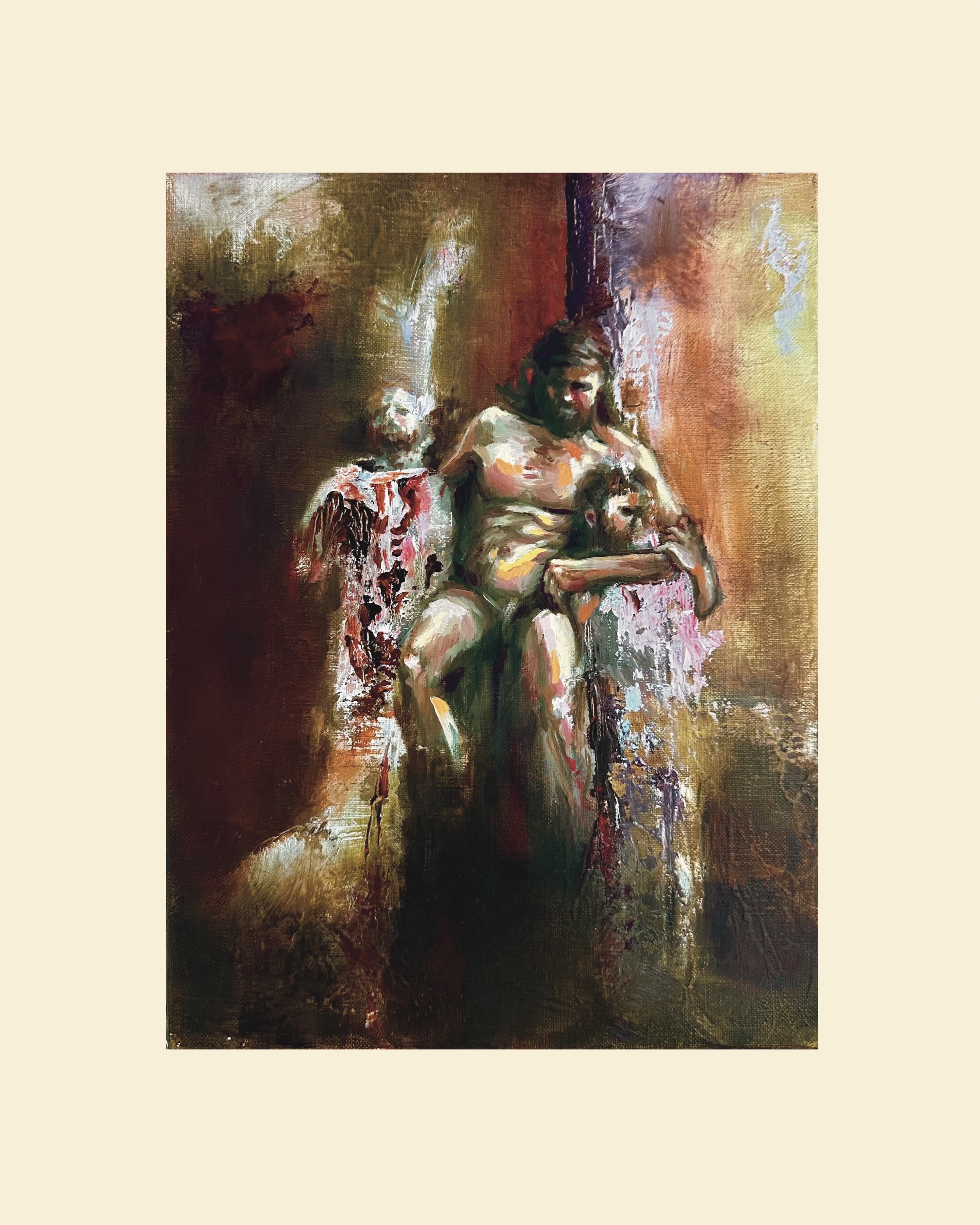

Painting Of Nikita Kruschev Inside The Sovietsky Hotel Photographed On August 21, 2013 By Omri Cohen.

Kazimir Malevich. “Bathers Seen From Behind,” (1908-1909). Courtesy The Collection Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam.

Kazimir Malevich. “The Woodcutter (recto) Peasant Women in Church (verso),” (1912). courtesy the Collection Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam.

Painting Of Joseph Stalin Inside The Sovietsky Hotel Photographed On August 21, 2013 By Omri Cohen.

Vadim Zakharov. “One Danaë,” (2013). Coin. Courtesy The Artist And Russian Pavilion, Venice Biennale.

Vadim Zakharov. “Danaë,” (2013). Installation Detail View. Courtesy The Artist And Russian Pavillion, Venice Biennale.

[](https://flaunt-mag.squarespace.com/config/pages/587fe9d4d2b857e5d49ca782#)[](https://flaunt-mag.squarespace.com/config/pages/587fe9d4d2b857e5d49ca782#)

I Knew About Black Squares Before You Did

Russian Art’s Dance With the Abstract and the Forbidden

In America, “avant-garde” is tossed around as shorthand for a particular aesthetic—one that connotes pointy clothes, black-and-white film, and aggressively enigmatic allegories for ennui. Once denoting bold radicalism and boundary-pushing in a broader social and political context, over time the term has become the province of art, film, and fashion; and avant-garde now represents the pursuit of the New in an exclusive matter of hipness and creative style. But in Russia, successive generations of the avant-garde, rather than chucking the past in pursuit of the future, have consistently sought to innovate by mining history when in need of reformation. In Russia that means two things—politics and paintings.

Abstract painter Kazimir Malevich wrote a manifesto for his nascent Suprematism movement in 1915, which read,

_Art no longer cares to serve the state and religion. Nothing in the objective world is as secure and unshakeable as it appears. We should accept nothing as predetermined or as constituted for eternity._

These and further thinly veiled threats against moral, class, and political order went beyond the art-historical, transforming a painting of a plain black square into an impossibly radical gesture far more incendiary than we can currently appreciate. Malevich’s reductivist compositions were in part interpretations of religious icon paintings, and he did borrow their powerful strategies of form and color to trigger contemplation—but he divorced that transcendent experience from dogmatic content, seeking to encourage independent thought in viewers, which in his time and place was as politically dangerous as any overt propaganda.

His manifesto continued,

_In my desperate attempt to free art from the ballast of objectivity, I took refuge in the square form and exhibited a picture which consisted of nothing more than a black square on a white field. The square seemed incomprehensible and dangerous to the critics and the public. And this, of course, was to be expected._

This kind of radicalism continued to resonate with subsequent generations of the avant-garde, swelling to occupy its own place of authority in Russian cultural history that became impossible to ignore even when that resonance eventually came to take the form of rejection and satire.

It has been 100 years since those events unfolded, and 90 years since the first important exhibition of 19th and 20th century Russian art—the Russian Art Show—was on view at Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum, making that venerable institution the first to show Suprematism outside of Russia. To mark the occasion, in October the museum presents “Kazimir Malevich and the Russian Avant-Garde.” The biggest Malevich survey mounted anywhere in decades, it explores the artist’s own youthful flirtations with Impressionism and Cubism, as well as the work of his peers—not to mention the bittersweet canvases of later years when Malevich ambiguously ended his career trying to inject abstraction into state-sanctioned compositions glorifying a construction of Russian nationalism. (An interesting aside: many of the Stedelijk works were collected during a time when abstract art was considered subversive and treasonous, and was banned in the Soviet Union.)

The members of Russian artist collective Blue Noses (founded in 1999 by Viacheslav Mizin and Alexander Shaburov) are also familiar with this kind of robust government censorship. Blue Noses are the authors of a prolific and exuberant body of work ranging from video and performance to photography, painting, and installation. Perhaps their best-known series (at least in the West) is “Kitchen Suprematism” (2005), a suite of 30 photos in which the best-known and most recognizable paintings from that school are recreated using common food items like processed lunch meats and heavy dark bread. It’s funny, smart, and a little ugly. Malevich’s effigy, embodied in a black square, is a recurring motif: Throughout numerous series such as “In Bed with Malevich” (2009), “Suprematist Bannermen” (2006); and “Sex-Suprematism” (2004), the most famous geometrical shape in Russian art appears in a variety of naked, hairy, costumed situations in public, in private, in the woods, and at civic landmarks.

But the work is not merely a playful art-school homage. It’s more like respectful, yet raunchy, hilarious, and slightly vicious satire. “The Russian cultural establishment has adopted a certain set of fetishes, fashionable styles, and authors. According to this set, everybody must esteem the Russian avant-garde of the early 20th century. Here the Blue Noses act as fetishists loving Malevich not less than sex,” Blue Noses said of the work. For all the lampooning of the craze for Malevich however, what Blue Noses was after in the moment of revolution through which they themselves were living when they made this work was no less bold in thought and implication for the broader social and political context than what Malevich had been after back in 1915. With all his “Art, at the turn of the century divested itself of the ballast of religious and political ideas which had been imposed upon it” business, Malevich was using the hegemony of religious icon painting as both his inspiration and his foil—just as 80 years later the Blue Noses would come to use him as theirs in taking on a state power structure. They all ended up in trouble with the cops.

Blue Noses didn’t get on the Kremlin’s shit-list because of the Malevich photographs. No, their brush with banishment came with the publication of An Epoch of Clemency (2005), a series of photos in which various couples are seen kissing in a birch tree grove—ballerinas, athletes, a Jew and a Muslim. It was the “Kissing Policemen” specifically that garnered notoriety when the Russian Minister of Culture called the picture “a disgrace” and prohibited it from being sent to a major exhibition in Paris. Several works were excluded, despite the group’s statement that they “wanted to show that here’s an era of mercy coming after the harsh 1990s, and two people are kissing. We admit there is something provocative in this. But if people just take it as pornography or eroticism, then it’s just silly in the end.” The Russian Culture and Press Ministry said the work was a “political provocation that will bring shame on Russia,” and the government got its way.

Like Malevich’s contemporaries, Blue Noses had an easier time outside the country. Galerie Volker Diehl, which operates in Moscow and Berlin, keeps track of the collective’s colleagues. As recently as Summer 2013, the artist Konstantin Altunin’s painting of Vladimir Putin and Dmitry Medvedev portrayed as ladies in lingerie was confiscated by the state and Altunin fled Russia for fear of retribution. Meanwhile, the Ilya and Emilia Kabakov documentary Enter Here is being released to great fanfare. Arguably Russia’s most celebrated contemporary artists and major figures of the international art scene of the 20th century, the husband-and-wife team is only now returning to Moscow (more or less), where they have been forbidden to show for decades. Yet they are being treated like prodigal luminaries, with major venues such as the Pushkin Museum and the State Hermitage Museum proudly claiming them for the national fold.

It is against this backdrop of paradox, fear, hope, contradiction, and mixed messages that Vadim Zakharov represented Russia in the 55th Biennale di Venezia with his exhibition Danaë. Curated by Udo Kittelmann (German support is getting to be a pattern), the sprawling and meticulously constructed, site-specific, and interactive performance installation occupied all the rooms of the Russian Pavilion with a processional, architectural, and kinetic experience. Interpreting historical traditions with contemporary realities, Zakharov takes the past in a future direction of ultra-modern, cross-platform, interdisciplinary, direct-experience, and co-creation. As with Suprematism, visitors to the Pavilion were prompted to discover the meaning of the art for themselves. Like Blue Noses’, Zakharov’s show hangs on a conceptual framework both inspired by and suspicious of the classicism of the past.

Based on the ancient Greek myth of Danaë, whom Zeus seduced with wealth before she became the mother of Perseus, Zakharov is using mythological archetypes exactly as intended—as armatures on which to hang contemporary commentary. The curator describes the experience of “a falling shower of gold \[also other material goods set in motion between rooms such as peanuts, rose petals, and people\] as an allegory for human desire and greed, but also to the corrupting influence of money.” Zakharov continues, “The appeal to Greek myth speaks of human values and sets off a mechanism of multiple glosses, including the Greek political and economic situation today. Europe is taking the role of Zeus, showering millions for the country’s stabilization and resurgence. Nobody yet knows what will be born from this merger. In any case, Greek culture always was and will be needed, particularly when mankind cannot find answers in the present. The Danaë project, like myth, gives rise to many commentaries.”

Zakharov characterizes his relationship to the Russian avant-garde and Malevich as bureaucratic and one of distance. “I have always fled any associations with Malevich in my work—perhaps just because I am bored of him—but in the Danaë project, for technical reasons, I cut a hole to the first floor in the form of a huge square; now I try to read the whole Danaë project anew, taking account of money falling through the Malevich square. It is not a reading that I wanted. But many persnickety viewers have found a union in the pattern of my installation between Malevich and Danaë; between my round hole in the floor with a view onto Rembrandt’s naked “Danaë” and in Duchamp’s “Étant donnés”; between the man sitting under the ceiling in the first hall and Rodin’s “The Thinker”; and many other things. A certain complex image of culture, with a corner for Malevich, has crept in incidentally without the author’s permission, as it were.

Kazimir Malevich. “Black Square,” (1929). Oil on canvas. 31 x 31 inches. Courtesy The State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

Kazimir Malevich. “Black Square,” (1929). Oil on canvas. 31 x 31 inches. Courtesy The State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

Lyubov Popova. “Painterly Architectonics,” (1918-1976). Oil on canvas. 29 x 19 inches. Courtesy The Greek State Museum of Contemporary Art, Costakis Collection, Thessaloniki.

Lyubov Popova. “Painterly Architectonics,” (1918-1976). Oil on canvas. 29 x 19 inches. Courtesy The Greek State Museum of Contemporary Art, Costakis Collection, Thessaloniki.

Gustav Klutsis. “Design for Loudspeaker No. 7,” (1922). Work on paper. 18 x 12 x 1 inches. Courtesy The Greek State Museum of Contemporary Art, Costakis Collection, Thessaloniki.

Gustav Klutsis. “Design for Loudspeaker No. 7,” (1922). Work on paper. 18 x 12 x 1 inches. Courtesy The Greek State Museum of Contemporary Art, Costakis Collection, Thessaloniki.

Mikhail Matyushin. “Landscape,” (1920). Oil on canvas on wood. 15 x 25 inches. Courtesy The Stedelijk Museum Khardzhiev-Chaga, Amsterdam.

Mikhail Matyushin. “Landscape,” (1920). Oil on canvas on wood. 15 x 25 inches. Courtesy The Stedelijk Museum Khardzhiev-Chaga, Amsterdam.

Vladimir Tatlin. “Courtier Costume Design For The Theatre Play Tsar Maksemyan,” (1911). Watercolor On Paper. 24 X 18 X 1 Inches. Courtesy The Stedelijk Museum Khardzhiev-Chaga, Amsterdam.

Vladimir Tatlin. “Courtier Costume Design For The Theatre Play Tsar Maksemyan,” (1911). Watercolor On Paper. 24 X 18 X 1 Inches. Courtesy The Stedelijk Museum Khardzhiev-Chaga, Amsterdam.

Aleksei Alekseevich Morgunov. “Cubofuturist Composition,” (1915). Work on paper. 34 x 24 inches. Courtesy The Stedelijk Museum Khardzhiev-Chaga, Amsterdam.

Aleksei Alekseevich Morgunov. “Cubofuturist Composition,” (1915). Work on paper. 34 x 24 inches. Courtesy The Stedelijk Museum Khardzhiev-Chaga, Amsterdam.

Kazimir Malevich. “Self-Portrait,” (1908-1910). Watercolor and gouache on paper. 11 x 11 inches. Courtesy The State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

Kazimir Malevich. “Self-Portrait,” (1908-1910). Watercolor and gouache on paper. 11 x 11 inches. Courtesy The State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

The Sovietsky Hotel Photographed On August 21, 2013 By Omri Cohen.

The Sovietsky Hotel Photographed On August 21, 2013 By Omri Cohen.

Painting Of Nikita Kruschev Inside The Sovietsky Hotel Photographed On August 21, 2013 By Omri Cohen.

Painting Of Nikita Kruschev Inside The Sovietsky Hotel Photographed On August 21, 2013 By Omri Cohen.

Kazimir Malevich. “Bathers Seen From Behind,” (1908-1909). Courtesy The Collection Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam.

Kazimir Malevich. “Bathers Seen From Behind,” (1908-1909). Courtesy The Collection Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam.

Kazimir Malevich. “The Woodcutter (recto) Peasant Women in Church (verso),” (1912). courtesy the Collection Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam.

Kazimir Malevich. “The Woodcutter (recto) Peasant Women in Church (verso),” (1912). courtesy the Collection Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam.

Painting Of Joseph Stalin Inside The Sovietsky Hotel Photographed On August 21, 2013 By Omri Cohen.

Painting Of Joseph Stalin Inside The Sovietsky Hotel Photographed On August 21, 2013 By Omri Cohen.

Vadim Zakharov. “One Danaë,” (2013). Coin. Courtesy The Artist And Russian Pavilion, Venice Biennale.

Vadim Zakharov. “One Danaë,” (2013). Coin. Courtesy The Artist And Russian Pavilion, Venice Biennale.

Vadim Zakharov. “Danaë,” (2013). Installation Detail View. Courtesy The Artist And Russian Pavillion, Venice Biennale.

[](https://flaunt-mag.squarespace.com/config/pages/587fe9d4d2b857e5d49ca782#)[](https://flaunt-mag.squarespace.com/config/pages/587fe9d4d2b857e5d49ca782#)

I Knew About Black Squares Before You Did

Russian Art’s Dance With the Abstract and the Forbidden

In America, “avant-garde” is tossed around as shorthand for a particular aesthetic—one that connotes pointy clothes, black-and-white film, and aggressively enigmatic allegories for ennui. Once denoting bold radicalism and boundary-pushing in a broader social and political context, over time the term has become the province of art, film, and fashion; and avant-garde now represents the pursuit of the New in an exclusive matter of hipness and creative style. But in Russia, successive generations of the avant-garde, rather than chucking the past in pursuit of the future, have consistently sought to innovate by mining history when in need of reformation. In Russia that means two things—politics and paintings.

Abstract painter Kazimir Malevich wrote a manifesto for his nascent Suprematism movement in 1915, which read,

_Art no longer cares to serve the state and religion. Nothing in the objective world is as secure and unshakeable as it appears. We should accept nothing as predetermined or as constituted for eternity._

These and further thinly veiled threats against moral, class, and political order went beyond the art-historical, transforming a painting of a plain black square into an impossibly radical gesture far more incendiary than we can currently appreciate. Malevich’s reductivist compositions were in part interpretations of religious icon paintings, and he did borrow their powerful strategies of form and color to trigger contemplation—but he divorced that transcendent experience from dogmatic content, seeking to encourage independent thought in viewers, which in his time and place was as politically dangerous as any overt propaganda.

His manifesto continued,

_In my desperate attempt to free art from the ballast of objectivity, I took refuge in the square form and exhibited a picture which consisted of nothing more than a black square on a white field. The square seemed incomprehensible and dangerous to the critics and the public. And this, of course, was to be expected._

This kind of radicalism continued to resonate with subsequent generations of the avant-garde, swelling to occupy its own place of authority in Russian cultural history that became impossible to ignore even when that resonance eventually came to take the form of rejection and satire.

It has been 100 years since those events unfolded, and 90 years since the first important exhibition of 19th and 20th century Russian art—the Russian Art Show—was on view at Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum, making that venerable institution the first to show Suprematism outside of Russia. To mark the occasion, in October the museum presents “Kazimir Malevich and the Russian Avant-Garde.” The biggest Malevich survey mounted anywhere in decades, it explores the artist’s own youthful flirtations with Impressionism and Cubism, as well as the work of his peers—not to mention the bittersweet canvases of later years when Malevich ambiguously ended his career trying to inject abstraction into state-sanctioned compositions glorifying a construction of Russian nationalism. (An interesting aside: many of the Stedelijk works were collected during a time when abstract art was considered subversive and treasonous, and was banned in the Soviet Union.)

The members of Russian artist collective Blue Noses (founded in 1999 by Viacheslav Mizin and Alexander Shaburov) are also familiar with this kind of robust government censorship. Blue Noses are the authors of a prolific and exuberant body of work ranging from video and performance to photography, painting, and installation. Perhaps their best-known series (at least in the West) is “Kitchen Suprematism” (2005), a suite of 30 photos in which the best-known and most recognizable paintings from that school are recreated using common food items like processed lunch meats and heavy dark bread. It’s funny, smart, and a little ugly. Malevich’s effigy, embodied in a black square, is a recurring motif: Throughout numerous series such as “In Bed with Malevich” (2009), “Suprematist Bannermen” (2006); and “Sex-Suprematism” (2004), the most famous geometrical shape in Russian art appears in a variety of naked, hairy, costumed situations in public, in private, in the woods, and at civic landmarks.

But the work is not merely a playful art-school homage. It’s more like respectful, yet raunchy, hilarious, and slightly vicious satire. “The Russian cultural establishment has adopted a certain set of fetishes, fashionable styles, and authors. According to this set, everybody must esteem the Russian avant-garde of the early 20th century. Here the Blue Noses act as fetishists loving Malevich not less than sex,” Blue Noses said of the work. For all the lampooning of the craze for Malevich however, what Blue Noses was after in the moment of revolution through which they themselves were living when they made this work was no less bold in thought and implication for the broader social and political context than what Malevich had been after back in 1915. With all his “Art, at the turn of the century divested itself of the ballast of religious and political ideas which had been imposed upon it” business, Malevich was using the hegemony of religious icon painting as both his inspiration and his foil—just as 80 years later the Blue Noses would come to use him as theirs in taking on a state power structure. They all ended up in trouble with the cops.

Blue Noses didn’t get on the Kremlin’s shit-list because of the Malevich photographs. No, their brush with banishment came with the publication of An Epoch of Clemency (2005), a series of photos in which various couples are seen kissing in a birch tree grove—ballerinas, athletes, a Jew and a Muslim. It was the “Kissing Policemen” specifically that garnered notoriety when the Russian Minister of Culture called the picture “a disgrace” and prohibited it from being sent to a major exhibition in Paris. Several works were excluded, despite the group’s statement that they “wanted to show that here’s an era of mercy coming after the harsh 1990s, and two people are kissing. We admit there is something provocative in this. But if people just take it as pornography or eroticism, then it’s just silly in the end.” The Russian Culture and Press Ministry said the work was a “political provocation that will bring shame on Russia,” and the government got its way.

Like Malevich’s contemporaries, Blue Noses had an easier time outside the country. Galerie Volker Diehl, which operates in Moscow and Berlin, keeps track of the collective’s colleagues. As recently as Summer 2013, the artist Konstantin Altunin’s painting of Vladimir Putin and Dmitry Medvedev portrayed as ladies in lingerie was confiscated by the state and Altunin fled Russia for fear of retribution. Meanwhile, the Ilya and Emilia Kabakov documentary Enter Here is being released to great fanfare. Arguably Russia’s most celebrated contemporary artists and major figures of the international art scene of the 20th century, the husband-and-wife team is only now returning to Moscow (more or less), where they have been forbidden to show for decades. Yet they are being treated like prodigal luminaries, with major venues such as the Pushkin Museum and the State Hermitage Museum proudly claiming them for the national fold.

It is against this backdrop of paradox, fear, hope, contradiction, and mixed messages that Vadim Zakharov represented Russia in the 55th Biennale di Venezia with his exhibition Danaë. Curated by Udo Kittelmann (German support is getting to be a pattern), the sprawling and meticulously constructed, site-specific, and interactive performance installation occupied all the rooms of the Russian Pavilion with a processional, architectural, and kinetic experience. Interpreting historical traditions with contemporary realities, Zakharov takes the past in a future direction of ultra-modern, cross-platform, interdisciplinary, direct-experience, and co-creation. As with Suprematism, visitors to the Pavilion were prompted to discover the meaning of the art for themselves. Like Blue Noses’, Zakharov’s show hangs on a conceptual framework both inspired by and suspicious of the classicism of the past.

Based on the ancient Greek myth of Danaë, whom Zeus seduced with wealth before she became the mother of Perseus, Zakharov is using mythological archetypes exactly as intended—as armatures on which to hang contemporary commentary. The curator describes the experience of “a falling shower of gold \[also other material goods set in motion between rooms such as peanuts, rose petals, and people\] as an allegory for human desire and greed, but also to the corrupting influence of money.” Zakharov continues, “The appeal to Greek myth speaks of human values and sets off a mechanism of multiple glosses, including the Greek political and economic situation today. Europe is taking the role of Zeus, showering millions for the country’s stabilization and resurgence. Nobody yet knows what will be born from this merger. In any case, Greek culture always was and will be needed, particularly when mankind cannot find answers in the present. The Danaë project, like myth, gives rise to many commentaries.”

Zakharov characterizes his relationship to the Russian avant-garde and Malevich as bureaucratic and one of distance. “I have always fled any associations with Malevich in my work—perhaps just because I am bored of him—but in the Danaë project, for technical reasons, I cut a hole to the first floor in the form of a huge square; now I try to read the whole Danaë project anew, taking account of money falling through the Malevich square. It is not a reading that I wanted. But many persnickety viewers have found a union in the pattern of my installation between Malevich and Danaë; between my round hole in the floor with a view onto Rembrandt’s naked “Danaë” and in Duchamp’s “Étant donnés”; between the man sitting under the ceiling in the first hall and Rodin’s “The Thinker”; and many other things. A certain complex image of culture, with a corner for Malevich, has crept in incidentally without the author’s permission, as it were.

Vadim Zakharov. “Danaë,” (2013). Installation Detail View. Courtesy The Artist And Russian Pavillion, Venice Biennale.

[](https://flaunt-mag.squarespace.com/config/pages/587fe9d4d2b857e5d49ca782#)[](https://flaunt-mag.squarespace.com/config/pages/587fe9d4d2b857e5d49ca782#)

I Knew About Black Squares Before You Did

Russian Art’s Dance With the Abstract and the Forbidden

In America, “avant-garde” is tossed around as shorthand for a particular aesthetic—one that connotes pointy clothes, black-and-white film, and aggressively enigmatic allegories for ennui. Once denoting bold radicalism and boundary-pushing in a broader social and political context, over time the term has become the province of art, film, and fashion; and avant-garde now represents the pursuit of the New in an exclusive matter of hipness and creative style. But in Russia, successive generations of the avant-garde, rather than chucking the past in pursuit of the future, have consistently sought to innovate by mining history when in need of reformation. In Russia that means two things—politics and paintings.

Abstract painter Kazimir Malevich wrote a manifesto for his nascent Suprematism movement in 1915, which read,

_Art no longer cares to serve the state and religion. Nothing in the objective world is as secure and unshakeable as it appears. We should accept nothing as predetermined or as constituted for eternity._

These and further thinly veiled threats against moral, class, and political order went beyond the art-historical, transforming a painting of a plain black square into an impossibly radical gesture far more incendiary than we can currently appreciate. Malevich’s reductivist compositions were in part interpretations of religious icon paintings, and he did borrow their powerful strategies of form and color to trigger contemplation—but he divorced that transcendent experience from dogmatic content, seeking to encourage independent thought in viewers, which in his time and place was as politically dangerous as any overt propaganda.

His manifesto continued,

_In my desperate attempt to free art from the ballast of objectivity, I took refuge in the square form and exhibited a picture which consisted of nothing more than a black square on a white field. The square seemed incomprehensible and dangerous to the critics and the public. And this, of course, was to be expected._

This kind of radicalism continued to resonate with subsequent generations of the avant-garde, swelling to occupy its own place of authority in Russian cultural history that became impossible to ignore even when that resonance eventually came to take the form of rejection and satire.

It has been 100 years since those events unfolded, and 90 years since the first important exhibition of 19th and 20th century Russian art—the Russian Art Show—was on view at Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum, making that venerable institution the first to show Suprematism outside of Russia. To mark the occasion, in October the museum presents “Kazimir Malevich and the Russian Avant-Garde.” The biggest Malevich survey mounted anywhere in decades, it explores the artist’s own youthful flirtations with Impressionism and Cubism, as well as the work of his peers—not to mention the bittersweet canvases of later years when Malevich ambiguously ended his career trying to inject abstraction into state-sanctioned compositions glorifying a construction of Russian nationalism. (An interesting aside: many of the Stedelijk works were collected during a time when abstract art was considered subversive and treasonous, and was banned in the Soviet Union.)

The members of Russian artist collective Blue Noses (founded in 1999 by Viacheslav Mizin and Alexander Shaburov) are also familiar with this kind of robust government censorship. Blue Noses are the authors of a prolific and exuberant body of work ranging from video and performance to photography, painting, and installation. Perhaps their best-known series (at least in the West) is “Kitchen Suprematism” (2005), a suite of 30 photos in which the best-known and most recognizable paintings from that school are recreated using common food items like processed lunch meats and heavy dark bread. It’s funny, smart, and a little ugly. Malevich’s effigy, embodied in a black square, is a recurring motif: Throughout numerous series such as “In Bed with Malevich” (2009), “Suprematist Bannermen” (2006); and “Sex-Suprematism” (2004), the most famous geometrical shape in Russian art appears in a variety of naked, hairy, costumed situations in public, in private, in the woods, and at civic landmarks.

But the work is not merely a playful art-school homage. It’s more like respectful, yet raunchy, hilarious, and slightly vicious satire. “The Russian cultural establishment has adopted a certain set of fetishes, fashionable styles, and authors. According to this set, everybody must esteem the Russian avant-garde of the early 20th century. Here the Blue Noses act as fetishists loving Malevich not less than sex,” Blue Noses said of the work. For all the lampooning of the craze for Malevich however, what Blue Noses was after in the moment of revolution through which they themselves were living when they made this work was no less bold in thought and implication for the broader social and political context than what Malevich had been after back in 1915. With all his “Art, at the turn of the century divested itself of the ballast of religious and political ideas which had been imposed upon it” business, Malevich was using the hegemony of religious icon painting as both his inspiration and his foil—just as 80 years later the Blue Noses would come to use him as theirs in taking on a state power structure. They all ended up in trouble with the cops.

Blue Noses didn’t get on the Kremlin’s shit-list because of the Malevich photographs. No, their brush with banishment came with the publication of An Epoch of Clemency (2005), a series of photos in which various couples are seen kissing in a birch tree grove—ballerinas, athletes, a Jew and a Muslim. It was the “Kissing Policemen” specifically that garnered notoriety when the Russian Minister of Culture called the picture “a disgrace” and prohibited it from being sent to a major exhibition in Paris. Several works were excluded, despite the group’s statement that they “wanted to show that here’s an era of mercy coming after the harsh 1990s, and two people are kissing. We admit there is something provocative in this. But if people just take it as pornography or eroticism, then it’s just silly in the end.” The Russian Culture and Press Ministry said the work was a “political provocation that will bring shame on Russia,” and the government got its way.

Like Malevich’s contemporaries, Blue Noses had an easier time outside the country. Galerie Volker Diehl, which operates in Moscow and Berlin, keeps track of the collective’s colleagues. As recently as Summer 2013, the artist Konstantin Altunin’s painting of Vladimir Putin and Dmitry Medvedev portrayed as ladies in lingerie was confiscated by the state and Altunin fled Russia for fear of retribution. Meanwhile, the Ilya and Emilia Kabakov documentary Enter Here is being released to great fanfare. Arguably Russia’s most celebrated contemporary artists and major figures of the international art scene of the 20th century, the husband-and-wife team is only now returning to Moscow (more or less), where they have been forbidden to show for decades. Yet they are being treated like prodigal luminaries, with major venues such as the Pushkin Museum and the State Hermitage Museum proudly claiming them for the national fold.

It is against this backdrop of paradox, fear, hope, contradiction, and mixed messages that Vadim Zakharov represented Russia in the 55th Biennale di Venezia with his exhibition Danaë. Curated by Udo Kittelmann (German support is getting to be a pattern), the sprawling and meticulously constructed, site-specific, and interactive performance installation occupied all the rooms of the Russian Pavilion with a processional, architectural, and kinetic experience. Interpreting historical traditions with contemporary realities, Zakharov takes the past in a future direction of ultra-modern, cross-platform, interdisciplinary, direct-experience, and co-creation. As with Suprematism, visitors to the Pavilion were prompted to discover the meaning of the art for themselves. Like Blue Noses’, Zakharov’s show hangs on a conceptual framework both inspired by and suspicious of the classicism of the past.

Based on the ancient Greek myth of Danaë, whom Zeus seduced with wealth before she became the mother of Perseus, Zakharov is using mythological archetypes exactly as intended—as armatures on which to hang contemporary commentary. The curator describes the experience of “a falling shower of gold \[also other material goods set in motion between rooms such as peanuts, rose petals, and people\] as an allegory for human desire and greed, but also to the corrupting influence of money.” Zakharov continues, “The appeal to Greek myth speaks of human values and sets off a mechanism of multiple glosses, including the Greek political and economic situation today. Europe is taking the role of Zeus, showering millions for the country’s stabilization and resurgence. Nobody yet knows what will be born from this merger. In any case, Greek culture always was and will be needed, particularly when mankind cannot find answers in the present. The Danaë project, like myth, gives rise to many commentaries.”

Zakharov characterizes his relationship to the Russian avant-garde and Malevich as bureaucratic and one of distance. “I have always fled any associations with Malevich in my work—perhaps just because I am bored of him—but in the Danaë project, for technical reasons, I cut a hole to the first floor in the form of a huge square; now I try to read the whole Danaë project anew, taking account of money falling through the Malevich square. It is not a reading that I wanted. But many persnickety viewers have found a union in the pattern of my installation between Malevich and Danaë; between my round hole in the floor with a view onto Rembrandt’s naked “Danaë” and in Duchamp’s “Étant donnés”; between the man sitting under the ceiling in the first hall and Rodin’s “The Thinker”; and many other things. A certain complex image of culture, with a corner for Malevich, has crept in incidentally without the author’s permission, as it were.