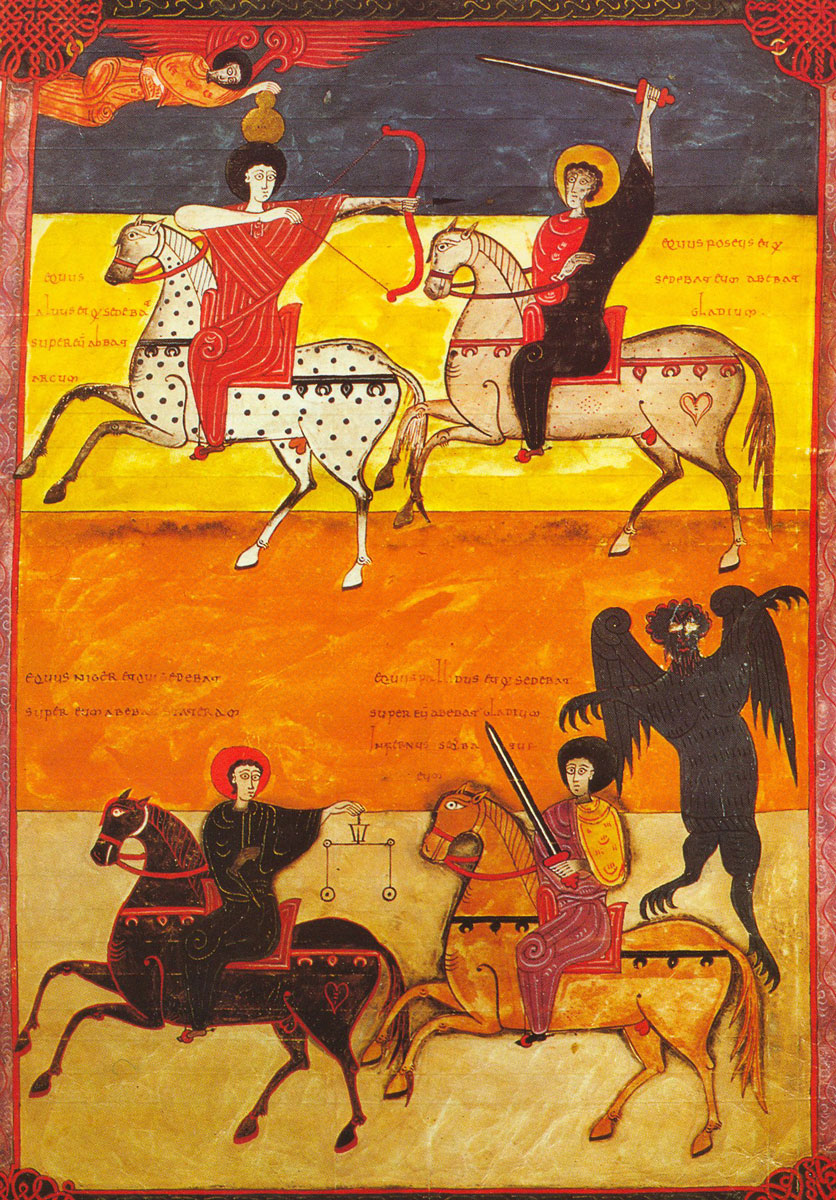

“THE FOUR HORSEMEN OF THE APOCALYPSE FROM BEATUS DE FALCUNDUS,” (1047). ILLUMINATED MANUSCRIPT. DIMENSIONS UNKNOWN.

[](#)[](#)

Column: Famines

The Armageddon Will Not Be Instagrammed

On a Sunday morning a couple years ago,

a Jehovah’s Witness came to my door. He was hunched and wilted, mopping his forehead with a handkerchief, and I assumed that mine was one of the last houses on his route. He wore a dark suit that looked like it’d been chosen for his own burial.

“I won’t keep you,” he said, fumbling with his literature.

I rested against the doorframe.

“Now,” he said, opening a book and pointing, “Jesus told His disciples that only Jehovah God knew when this system of things—the world as you and I know it—would come to an end. But Jesus did foretell some many things that’d happen just before the last days. Now, brother, would you believe it if I told you those things are just now taking place?”

I looked over his shoulder. Two old ladies were watching us from the backseat of an Oldsmobile parked across the street.

“You follow the news, son?”

“Sometimes.”

“Matthew 24:7, ‘Nation will rise against nation and kingdom against kingdom,’ ‘There will be food shortages.’” He flipped to another dog-eared page, clearly having found his groove. “Luke 21:11, ‘There will be great earthquakes…pestilences.’ You see? There’s murder of all kinds, unimaginable rape. This universal indifference to human life, this moral famine, that’s what’s gonna bring Armageddon straight to your very doorstep.”

“You want me to agree that things are worse now than they’ve ever been,” I said.

He shrugged and looked around, as if things were getting worse right there, in my front yard.

“Things have been terrible forever,” I said. “If anything, with all the new scientific developments and everything, I feel like the world could be getting better.”

“New scientific developments,” he said, shaking his head. “Getting better.” He looked at his shoes, which had been lazily polished. “But if these _are_ the end times, wouldn’t you feel good knowing that you, brother, have a place in the Kingdom of Heaven?”

“Actually, I find the possibility of an afterlife and the paralyzing boredom that’d no doubt accompany eternal happiness pretty terrifying. I mean, Heaven is like this endless vacation, right? But without work or goals or deadlines even vacation becomes it’s own kind of toil. Filling the hours would be maddening. And since there’d no longer be a separation between God and man, he’d be constantly watching over everybody like a bouncer. At least on Earth we’re allowed to be miserable.”

“Well,” he said, closing his book.

I worry about that conversation, sometimes, usually after reading this or that bleak news story about this or that nation starving to death across the world. The reaction to these horrific conditions, to constant poverty—entire populations of destitute refugees—by more affluent countries is much like my own reaction: tacit worry. In Peter Singer’s 1972 essay “Famine, Affluence, and Morality,” he argues that “the prevention of the starvation of millions of people outside our society must be considered at least as pressing as the upholding of property norms within our society.” But it hasn’t been, and it probably won’t be, and this is due to our own moral famine. This, according to that perspiring lackey for the Jehovah’s Witnesses, will beget the biblical apocalypse.

So what?

On September 11, 2001, American Airlines Flight 11 crashed into the North Tower of the World Trade Center. A friend of a friend was living in Lower Manhattan at the time, and after the windows of her apartment imploded it allegedly took her 10 minutes to find the right shoes to wear. The phenomenological approach to this type of behavior maintains that when shit hits the fan and things overstep rational understanding, the human mind tends to slip through a psychological trapdoor in order to maintain some semblance of equilibrium. But it’s also possible that friend of a friend was simply suffering from her own moral famine, her own vacuous numbness, and she was just _so over it_. This is the modern reaction to tragedy, and it becomes, in effect, a great defense mechanism.

I drive up and down Hollywood Boulevard and see the girls queuing outside clubs, encased in cotton spandex and tittering like summer birds, each one an echo of the other, or the guys and their silly pantomime of machismo, and I wonder how we’ll react when it’s finally The End.

“OMG this geomagnetic reversal is totally bumming me out,” one might Tweet.

“No cell service downtown? Either AT&T sucks or there’s been a total breakdown of modern technology!” another could post on Facebook.

Incoming gamma-ray bursts will be photographed and Instagrammed, megatsunamis swallowing our shorelines Vined. We will, as per Britney’s suggestion, _dance until the world ends_. And this will be the last question that flashes through our minds in that final downpour of magma and ash, as every peripheral nerve fiber in our burning bodies fires at once like so many spark plugs: “Does the third horseman of the apocalypse look cooler in Valencia or Earlybird?”

#nofilter, obviously.