[](#)[](#)

The Getty Center: Made In The Image And Likeness Of Self

The Getty Center, commenced in 1984, and opened in 1997, now possesses more viewing options than Netflix, and offers more rewarding search results than Google—but underneath its quiet campus, a clandestine network of art historians and research scientists facilitate groundbreaking interrogation, working to answer millennium-old questions of authenticity, materiality, circumstance, and transition—in one word, history— which might write over the fables once agreed upon.

“Sometimes we have to use our imagination a bit when investigating historical events.” – J. Paul Getty

Upon Jean Paul Getty’s death in 1976, to the surprise of Art and family, he left $700 million—much of his estate—to a group of trustees. The Getty Trust, as it was ordained, was to use this money for the “Diffusion of Art and General Knowledge.” Clarifying the terms, and releasing these funds, proved an ontologically supreme task—the trust surpassed $1 billion before finally being settled and put to use. In 1982, the Getty Research Institute opened atop a browning chaparral bluff in the Brentwood neighborhood of the Santa Monica Mountains in Los Angeles.

In unanimity, the campus today hosts the Getty Research Institute, the Getty Conservation Institute, one of two Getty Museum locations (the second is the Getty Villa, in Malibu), and the Getty Trust: now the highest valued arts research trust in the world at $6.7 billion.

Gazing West from the central courtyard, ten miles inland from the coast, one might scan the houses lining numerous saddleback drives winding through hill after hill leading towards the glimmering blue Pacific Ocean. The rare vestige of virgin L.A. landscape is said to have reminded Getty Center architect Richard Meier of Tuscan hillsides. Meier proposed a design relying heavily on polished travertine, but it didn’t appeal to Brentwood trustees. The architect countered with a suggestion that the entire campus use rough travertine, raw with exposed fossils. The trustees were satisfied.

Outside, well beyond the rumbling din of the 405 Freeway, Meier’s fibrous rock surfaces attenuate the California sun, imposing a soft, natural light. Stone surfaces, steel framing, and glass facades; the entire campus is essentially made from three materials.

Through a glass entryway, past a curved reception desk, staff members exchange Chinese currency for American dollars. Through carpeted hallways, as one scuffles past a series of doors, security guards attend to monitors and radios, checking that every entrant carries proper clearance. One is reminded of the contemporary mega church—a sense of intense serenity wrapped delicately in a silencing religiosity. A left turn leads towards the Getty Research Institute’s Special Collections.

Here, concentric shelves interspersed with private desks lead to a circle of travertine that sits directly beneath a glass oculus. It basks in a thick beam of golden sunlight at one in the afternoon on the Summer Solstice. On any given day a respected architectural writer (and UCLA professor) in his late 70s might be found on a nearby cushioned seat, reclining in slumber, an aged baseball cap draped over his pursed lips.

Inside a multi-room studio/lab facility of the Getty Conservation Institute, a scientist jots down vitals on a clipboard. Her eyes move from the sheets resting on her non-writing arm, to an elevated, square operating table. Above the setup, a series of tubes hang down and attach to a sealed bag. Below, tilted circular gauges display pressure and temperature. Flat inside the bubble, lies the central panel of a 15th C. altarpiece of medium size, roughly four by eight feet, tempera and gold on wood. The painting is that of Giovanni di Paolo, of Siena, Tuscany. As you pass by, please don’t break out your selfie-stick.

“Oh, you’re photographing, but you can’t publish that because it doesn't belong to us,” says conservator Yvonne Szafran. Stern and congenial, she’s spectacled, stylishly academic. She wears light-tan low-cut riding boots. “I guess if you don’t get any paintings, that’s okay.”

One time the Getty allowed an innocent photo to appear on a blog, explains Szafran. “Someone zoomed in on a high- res photo and caught something they weren’t supposed to see.” Szafran laughs as she chides, projecting the authority and intelligence suitable for a real-life archaeology journey. Though her pursuit for historical comprehension involves less exotic scenery and more routine lab work.

Perpendicular to Szafran’s workspace, a tempera, gold, and ink parchment rests on an easel. It’s a lower portion of di Paolo’s altarpiece. An adjacent easel holds a sheet with four even squares, each a variation of some amorphous shape. Like ghostly blue-grey negatives, they resemble enriched x-rays. Warholian ephemera? Perhaps not.

These are test results contextualizing the history of di Paolo’s altarpiece. Szafran and her colleagues have spent the past months analyzing three different di Paolo compositions. Over 450 years ago, these parchments and wood panels might have endured a sanitary, serene existence within a Sienese church. through stained glass windows, one might have turned from Di Paolo’s secular artwork and caught sweeping hillsides, curving steeply down into the Mediterranean coast, filtered red and blue through the stained glass panels. It’s a startlingly familiar overlap, one Mediterranean climate to the next.

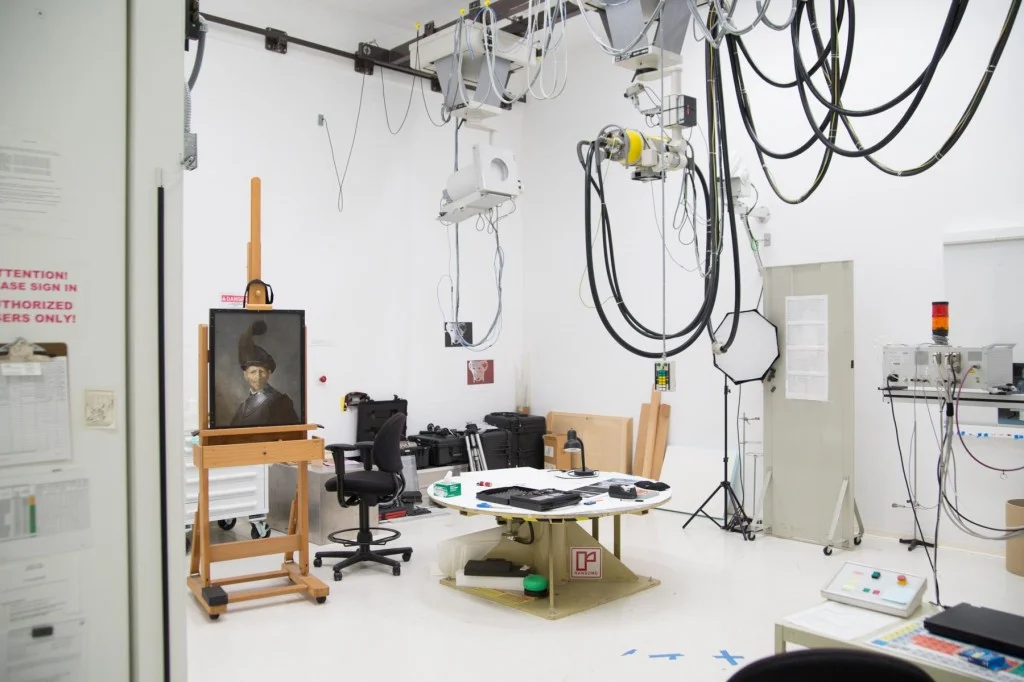

Back in the conservatory, about 50 feet north of Szafran’s desk and through a long, quiet, open office space, one finds a cream-colored door. It opens into a shielded chamber that feels like a dated x-ray room or the front desk of a public school library. Here, a team of international scientists and historians conduct x-rays as well as infrared reflectography. The ceiling hangs over 20 feet overhead to give clearance for the arm of the x-ray tube. Szafran jests, “It’s a bit like a medical x-ray, but our patients don’t move.” So why would anyone examine a painting in such detail? Fraud for one, something J. Paul Getty dealt with throughout his lifetime as an art collector. There’s something ancient, divinely comedic, in imagining a tale of a rich fool. A man of great means and limited understanding meets a man of limited means and wider knowledge. The ending writes itself.

“It’s like detective work. We want to know everything we can about a painting before we begin to study it,” Szafran says. Having spent decades in the field, she’s seen the technological leaps. Leaving the x-ray chamber, “old technology” as Szafran calls it, since scientists have been using this method since around 1900. Outside, a short hallway leads to an intimidating metal door.

“That’s where we conduct electron microscopy and hyperspectrum analysis.” After a half hour with Szafran, it begins to feel normal for 500-year old paintings to perch unframed on sturdy easels, while equipment that might have helped launch humans into outer space waits for further command.

Assuming proper security clearance, one might pass through another security door to find research lab associate David Carson. He works with the Science department, analyzing inorganic building materials.

“An electron microscope works like a old black and white TV,” he says with a scientific, confident tone. “Each pixel gives you a different greyscale intensity, the different shades become a black and white image. You’re limited on the wavelength of light, and that’s why you use electrons.” Using elemental analysis, Carson and his team can determine the concentration of iron, lead, or any other relevant element. He reaches for a small cubic sample on his desk, about two inches on each side.

“This is a piece from a building in Brazil that was destroyed. A \[Getty Research Institute\] scholar wanted to understand the mortar. As we move from the white mortar, to calcium carbonate and sand, you get into the paint layers—zinc and barium, moves to iron, and then we get titanium dioxide, modern pigments. we can figure out every time this building was painted since it was constructed.”

Speaking naïvely, Carson’s lab feels aesthetic, like a retrofitted set from Barbarella—heat chambers with round rotary windows, vacuum chambers with sliding glass doors—but Carson isn’t representing an ideal.

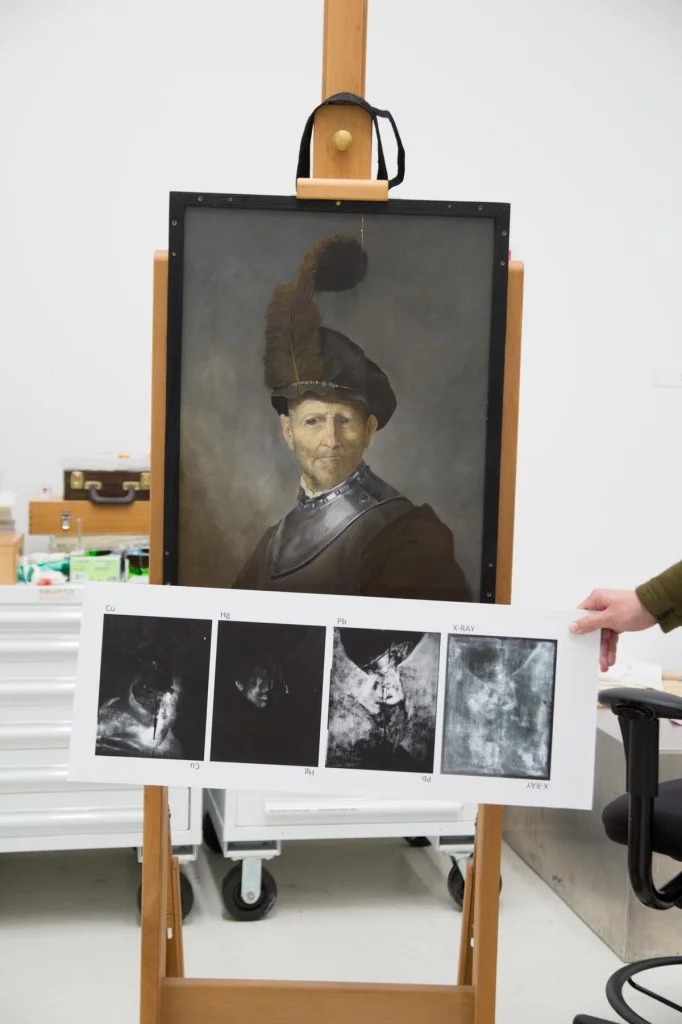

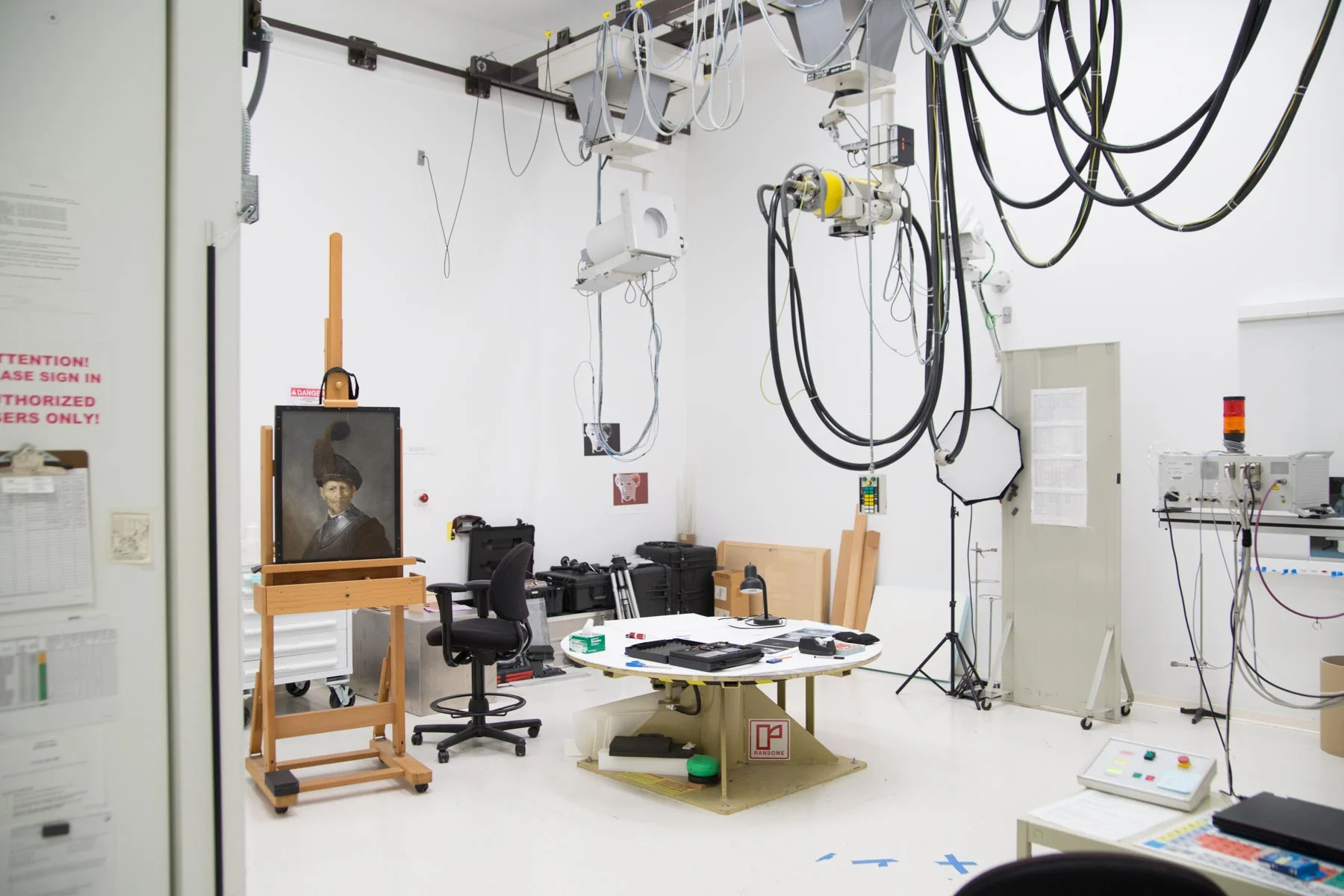

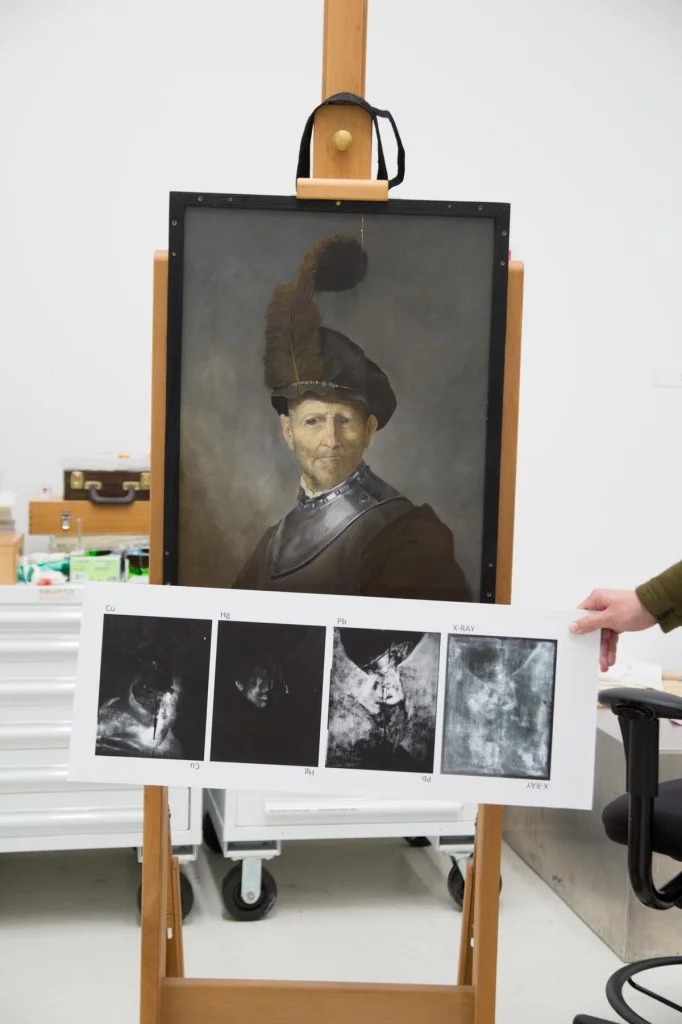

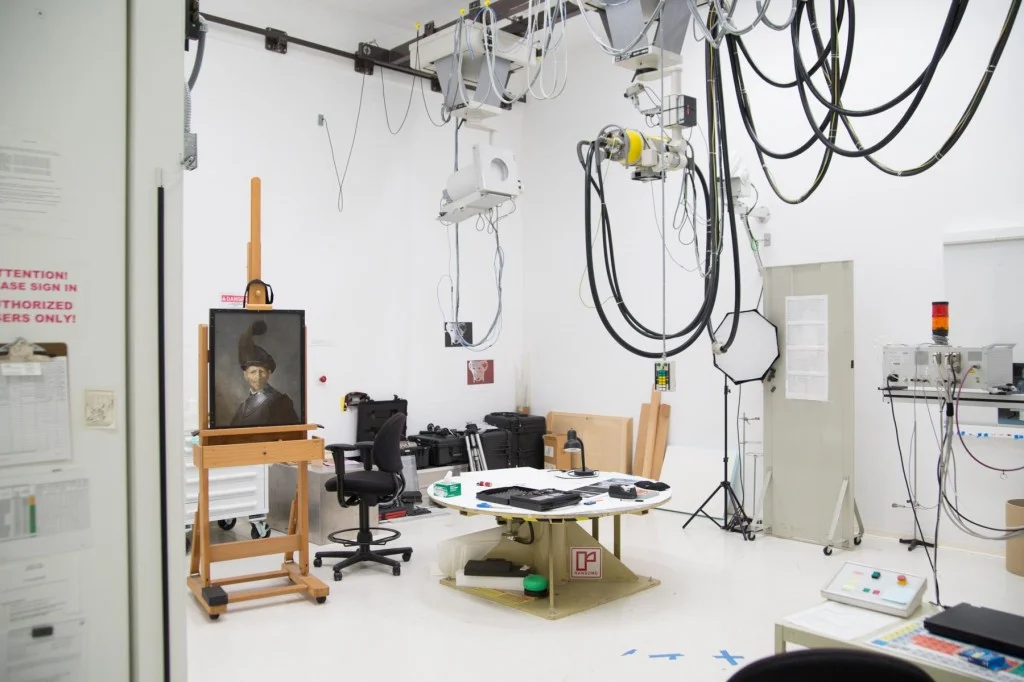

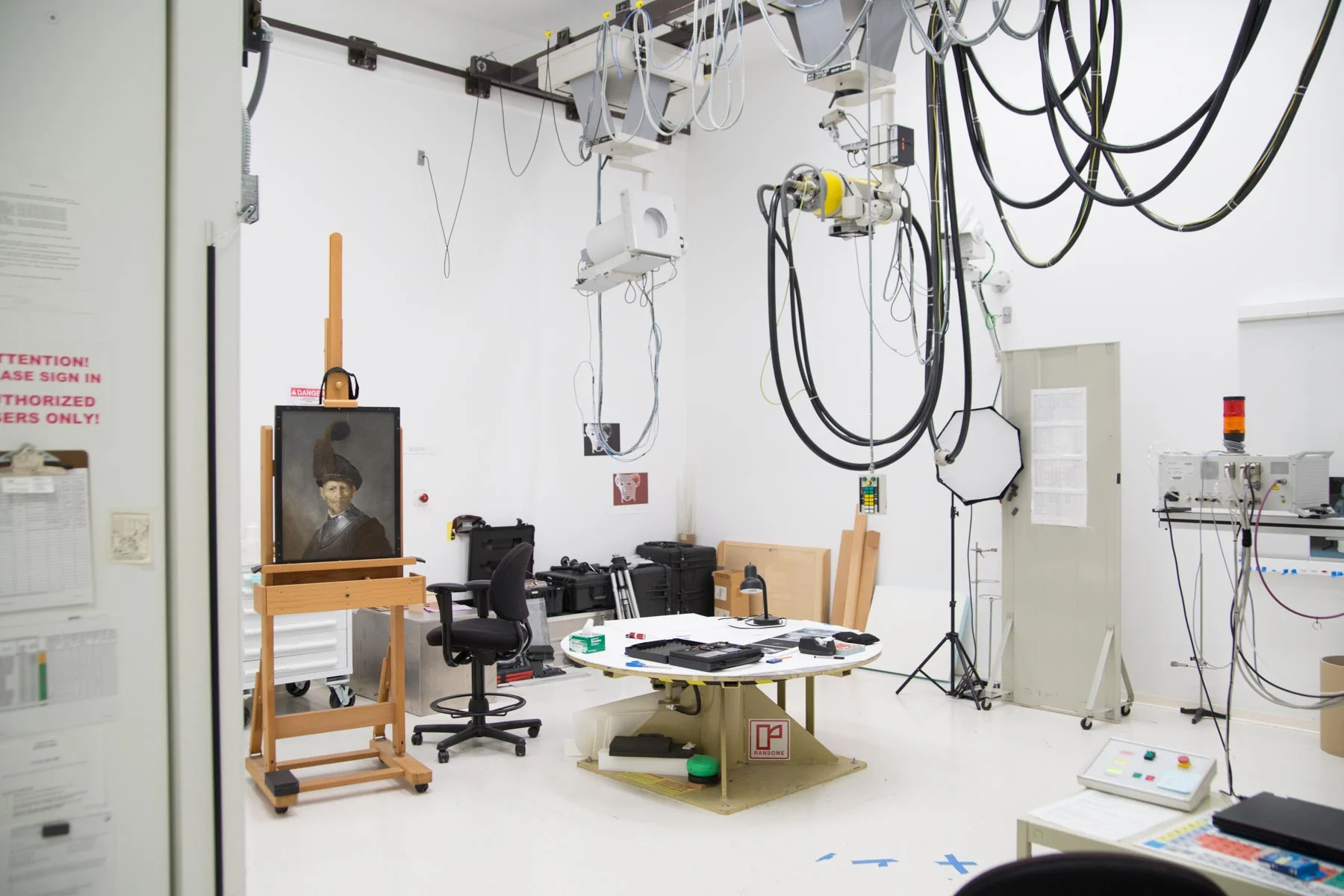

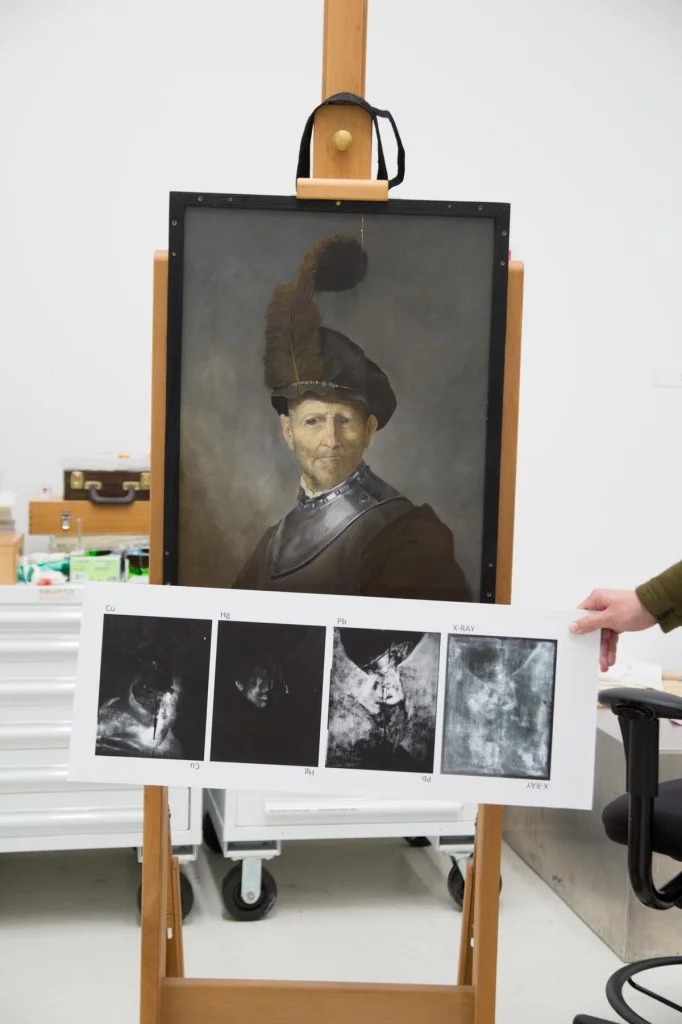

“We don’t just take samples to take samples. It depends on the question the scholar is asking.” That’s not to say that Carson’s work entails any less imagination. In a recessed chamber, one can find an easel, and what appears to be a Rembrandt oil painting, “Old Man in Military Costume.” “This is not a real painting. This is a mockup,” announces Carson. “This was made by an intern.”

After importing a new technology, the Getty Institute assessed the elemental composition of the real painting. The conservators are so adept at relating elemental components with pigments used to mix paint, they not only recreate what’s on the surface, they determine what’s underneath it.

“Our x-ray radiography reveals that there was a painting underneath the painting,” Carson explains. “And if we turn \[the results\] upside down, you’ll see there’s another face.”

The replica painting was made for a high-powered x-ray at Stanford University. They wanted to test the copy first to see if the process damaged it before running the test on the actual Rembrandt.

Unfortunately, much like master painters, Getty scientists find themselves caught in the creative vortex of time. In this case, the Getty found that by the time they’d prepared the duplicate for its fated Stanford test, a newer, better technology had come to market. In the end, the preliminary test wasn’t necessary, leaving the impersonation without a cause.

Of artist Stephen Kaltenbach’s numerous works—postmodern sculptures, extra large, dual perspective paintings—his conceptualist work carries a weighty potential, a humorous “spring constant.” In a letter to NASA, in anticipation of Apollo 11, Kaltenbach pithily explains his sculpture, a gift to Neil Armstrong. It was of a boot with a relief of a bare foot underneath. He hoped America might leave a footprint on the moon, of an astronaut who’d forgotten to put on one of his boots.

Meanwhile, the technician holds her _contrapposto_ pose for minutes at a time, nodding down to mark her sheet, nodding up to observe. Wearing de facto university lab goggles and a white apron, one might ask, is a quarantine in effect? Seeing my concern, Szafran confides, “we’ve taken out all the oxygen \[from the bagged painting\] and replaced it with nitrogen. If there’s anything inside, they’re not going to survive this treatment.” Given that even invaluable works of art are prone to infestation, one might sigh, in relief that anything resists entropy, time. “This is standard practice,” assures Szafran. “This is unlikely but there were certain signs that made us suspicious. This is a precaution more than anything else. We’ll feel better at the end.”

In the analysis of a painting based on the prevalence of specific compounds (in the case of this Tuscan altarpiece, gold factored in heavily), conservators can assert where it was likely to have been painted, what conditions it weathered, possibly even what historical events it lived through.

“Some artists have better technique than others,” Szafran says. “If you go back to the 16th century or even earlier, the first thing these artists had to do was learn how to make paint.” This consistency in pigmentation adds substance to the narrative of a painting. Because today’s mass-produced acrylics are less than a century old, science can only trust models to predict long-term patterns of deterioration.

“In the 20th century, they started using house paint. it’s interesting but it’s hard to take care of.” Szafran sighs. So what happens when today’s artists use blood, feces, vomit, and/or roadkill to fully express man’s eternal struggles?

“We call these ‘inherent vices,’” Szafran explains coolly. “And yes, curators and representatives have to ask artists things like, ‘when the cigarette butt falls off, how would you like us to deal with that?” But whom does the curator ask when the artist is dead? “Once they die it becomes more difficult. It’s generated a lot of conversation, whole conferences are dedicated to it.”

Today’s painters are likely to swipe a smartphone or flip open a laptop to order blue paint. They won’t dodge the radial needles of a yucca bush in pursuit of dried juniper berries. There’s nothing to dominate. Nature’s no longer natural. “\[Early\] artists were very conscious of making a painting that would last.”

The way Szafran sees it; today’s artists aren’t concerned with longevity. What satisfaction is there for death, waiting, like the defunct Rembrandt replica, somewhere in a Getty basement, when met with today’s artist? “I’ve been waiting for you,” death might say. “Take me,” the artist might say.

As for the next generation of Szafrans and Carsons, historians of art—proliferates of content and documentation—what will their work entail? Could you imagine finding a shattered silicate from beneath the rubble of Madison Square Garden in 2200? Would you work backwards through ones and zeroes, beginning with a database of genetic coding, to try and figure the exact second that Kanye, if it was Kanye, smashed his phone in a fit of rage?

Perhaps Getty spoke his own truth when he said every history is nothing more than a colorful recreation. The Getty is the finest source of recreation of the past, and joy of its enablers echoes through its longest, most dampened, most secure hallways.

_Photographer: [William Converse-Richter](http://william-converserichter-gybc.squarespace.com/)._

[](#)[](#)

The Getty Center: Made In The Image And Likeness Of Self

The Getty Center, commenced in 1984, and opened in 1997, now possesses more viewing options than Netflix, and offers more rewarding search results than Google—but underneath its quiet campus, a clandestine network of art historians and research scientists facilitate groundbreaking interrogation, working to answer millennium-old questions of authenticity, materiality, circumstance, and transition—in one word, history— which might write over the fables once agreed upon.

“Sometimes we have to use our imagination a bit when investigating historical events.” – J. Paul Getty

Upon Jean Paul Getty’s death in 1976, to the surprise of Art and family, he left $700 million—much of his estate—to a group of trustees. The Getty Trust, as it was ordained, was to use this money for the “Diffusion of Art and General Knowledge.” Clarifying the terms, and releasing these funds, proved an ontologically supreme task—the trust surpassed $1 billion before finally being settled and put to use. In 1982, the Getty Research Institute opened atop a browning chaparral bluff in the Brentwood neighborhood of the Santa Monica Mountains in Los Angeles.

In unanimity, the campus today hosts the Getty Research Institute, the Getty Conservation Institute, one of two Getty Museum locations (the second is the Getty Villa, in Malibu), and the Getty Trust: now the highest valued arts research trust in the world at $6.7 billion.

Gazing West from the central courtyard, ten miles inland from the coast, one might scan the houses lining numerous saddleback drives winding through hill after hill leading towards the glimmering blue Pacific Ocean. The rare vestige of virgin L.A. landscape is said to have reminded Getty Center architect Richard Meier of Tuscan hillsides. Meier proposed a design relying heavily on polished travertine, but it didn’t appeal to Brentwood trustees. The architect countered with a suggestion that the entire campus use rough travertine, raw with exposed fossils. The trustees were satisfied.

Outside, well beyond the rumbling din of the 405 Freeway, Meier’s fibrous rock surfaces attenuate the California sun, imposing a soft, natural light. Stone surfaces, steel framing, and glass facades; the entire campus is essentially made from three materials.

Through a glass entryway, past a curved reception desk, staff members exchange Chinese currency for American dollars. Through carpeted hallways, as one scuffles past a series of doors, security guards attend to monitors and radios, checking that every entrant carries proper clearance. One is reminded of the contemporary mega church—a sense of intense serenity wrapped delicately in a silencing religiosity. A left turn leads towards the Getty Research Institute’s Special Collections.

Here, concentric shelves interspersed with private desks lead to a circle of travertine that sits directly beneath a glass oculus. It basks in a thick beam of golden sunlight at one in the afternoon on the Summer Solstice. On any given day a respected architectural writer (and UCLA professor) in his late 70s might be found on a nearby cushioned seat, reclining in slumber, an aged baseball cap draped over his pursed lips.

Inside a multi-room studio/lab facility of the Getty Conservation Institute, a scientist jots down vitals on a clipboard. Her eyes move from the sheets resting on her non-writing arm, to an elevated, square operating table. Above the setup, a series of tubes hang down and attach to a sealed bag. Below, tilted circular gauges display pressure and temperature. Flat inside the bubble, lies the central panel of a 15th C. altarpiece of medium size, roughly four by eight feet, tempera and gold on wood. The painting is that of Giovanni di Paolo, of Siena, Tuscany. As you pass by, please don’t break out your selfie-stick.

“Oh, you’re photographing, but you can’t publish that because it doesn't belong to us,” says conservator Yvonne Szafran. Stern and congenial, she’s spectacled, stylishly academic. She wears light-tan low-cut riding boots. “I guess if you don’t get any paintings, that’s okay.”

One time the Getty allowed an innocent photo to appear on a blog, explains Szafran. “Someone zoomed in on a high- res photo and caught something they weren’t supposed to see.” Szafran laughs as she chides, projecting the authority and intelligence suitable for a real-life archaeology journey. Though her pursuit for historical comprehension involves less exotic scenery and more routine lab work.

Perpendicular to Szafran’s workspace, a tempera, gold, and ink parchment rests on an easel. It’s a lower portion of di Paolo’s altarpiece. An adjacent easel holds a sheet with four even squares, each a variation of some amorphous shape. Like ghostly blue-grey negatives, they resemble enriched x-rays. Warholian ephemera? Perhaps not.

These are test results contextualizing the history of di Paolo’s altarpiece. Szafran and her colleagues have spent the past months analyzing three different di Paolo compositions. Over 450 years ago, these parchments and wood panels might have endured a sanitary, serene existence within a Sienese church. through stained glass windows, one might have turned from Di Paolo’s secular artwork and caught sweeping hillsides, curving steeply down into the Mediterranean coast, filtered red and blue through the stained glass panels. It’s a startlingly familiar overlap, one Mediterranean climate to the next.

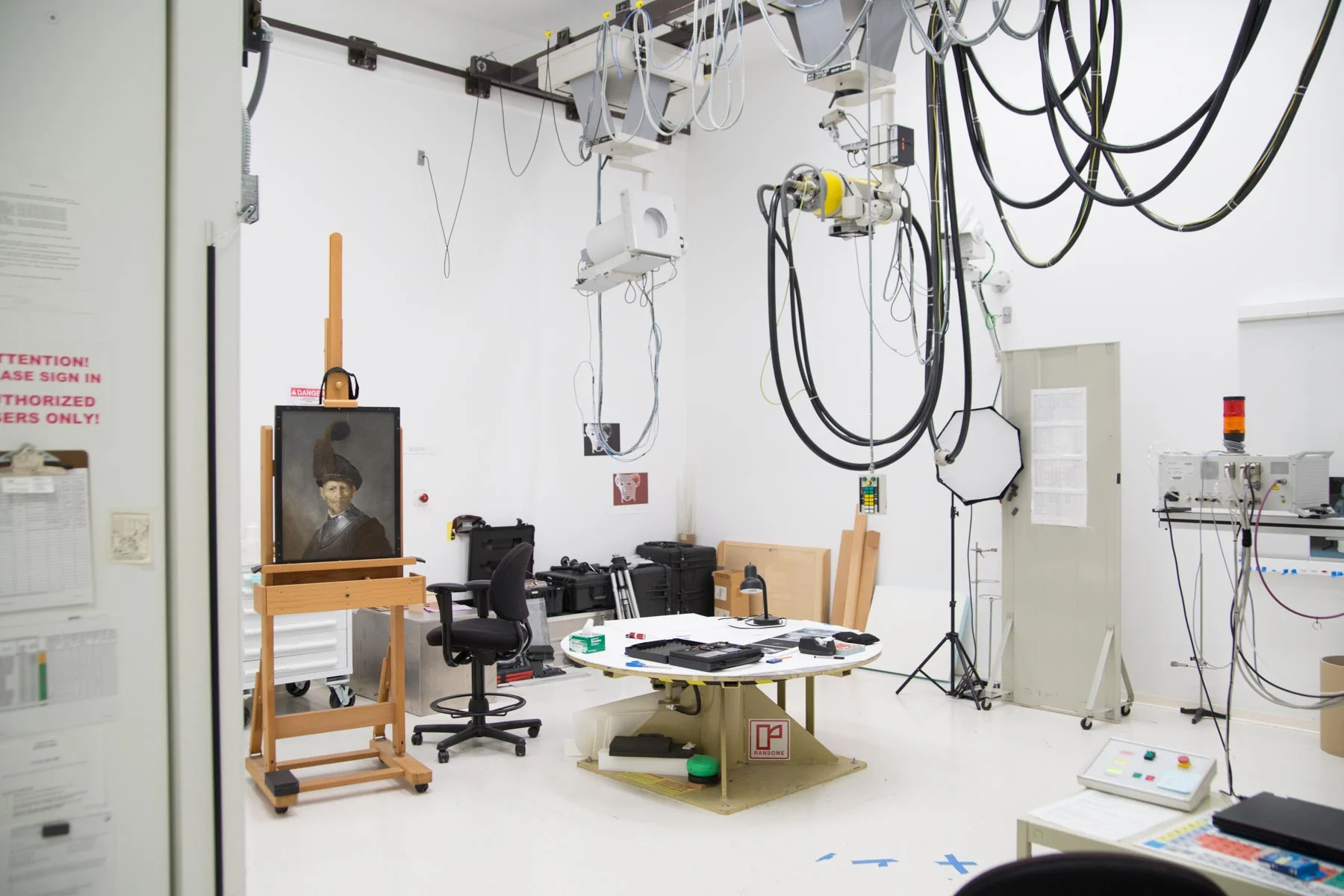

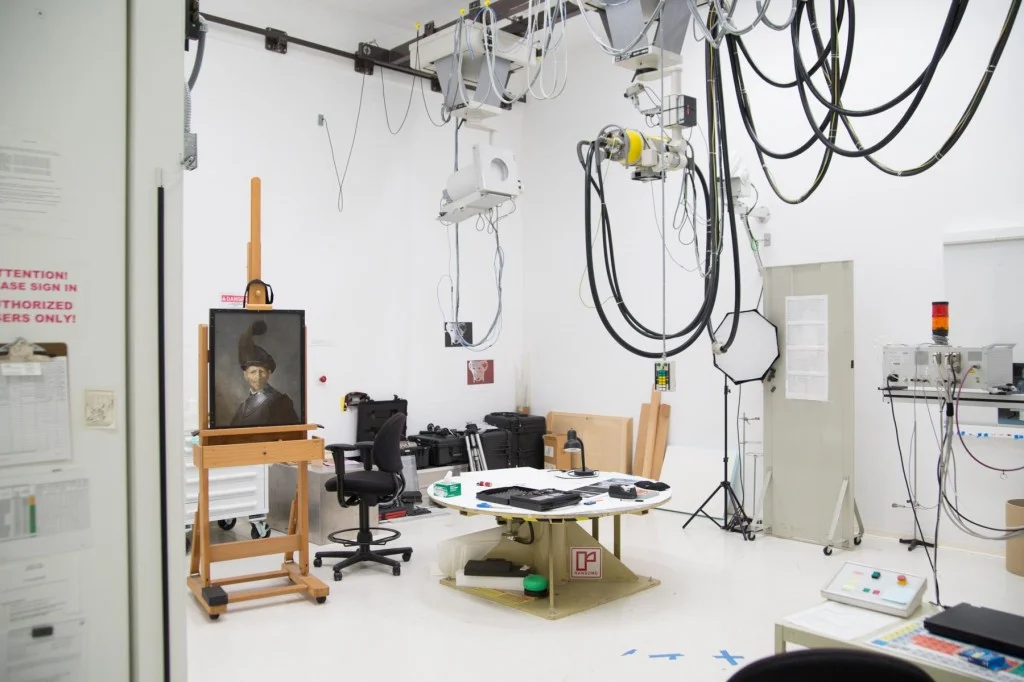

Back in the conservatory, about 50 feet north of Szafran’s desk and through a long, quiet, open office space, one finds a cream-colored door. It opens into a shielded chamber that feels like a dated x-ray room or the front desk of a public school library. Here, a team of international scientists and historians conduct x-rays as well as infrared reflectography. The ceiling hangs over 20 feet overhead to give clearance for the arm of the x-ray tube. Szafran jests, “It’s a bit like a medical x-ray, but our patients don’t move.” So why would anyone examine a painting in such detail? Fraud for one, something J. Paul Getty dealt with throughout his lifetime as an art collector. There’s something ancient, divinely comedic, in imagining a tale of a rich fool. A man of great means and limited understanding meets a man of limited means and wider knowledge. The ending writes itself.

“It’s like detective work. We want to know everything we can about a painting before we begin to study it,” Szafran says. Having spent decades in the field, she’s seen the technological leaps. Leaving the x-ray chamber, “old technology” as Szafran calls it, since scientists have been using this method since around 1900. Outside, a short hallway leads to an intimidating metal door.

“That’s where we conduct electron microscopy and hyperspectrum analysis.” After a half hour with Szafran, it begins to feel normal for 500-year old paintings to perch unframed on sturdy easels, while equipment that might have helped launch humans into outer space waits for further command.

Assuming proper security clearance, one might pass through another security door to find research lab associate David Carson. He works with the Science department, analyzing inorganic building materials.

“An electron microscope works like a old black and white TV,” he says with a scientific, confident tone. “Each pixel gives you a different greyscale intensity, the different shades become a black and white image. You’re limited on the wavelength of light, and that’s why you use electrons.” Using elemental analysis, Carson and his team can determine the concentration of iron, lead, or any other relevant element. He reaches for a small cubic sample on his desk, about two inches on each side.

“This is a piece from a building in Brazil that was destroyed. A \[Getty Research Institute\] scholar wanted to understand the mortar. As we move from the white mortar, to calcium carbonate and sand, you get into the paint layers—zinc and barium, moves to iron, and then we get titanium dioxide, modern pigments. we can figure out every time this building was painted since it was constructed.”

Speaking naïvely, Carson’s lab feels aesthetic, like a retrofitted set from Barbarella—heat chambers with round rotary windows, vacuum chambers with sliding glass doors—but Carson isn’t representing an ideal.

“We don’t just take samples to take samples. It depends on the question the scholar is asking.” That’s not to say that Carson’s work entails any less imagination. In a recessed chamber, one can find an easel, and what appears to be a Rembrandt oil painting, “Old Man in Military Costume.” “This is not a real painting. This is a mockup,” announces Carson. “This was made by an intern.”

After importing a new technology, the Getty Institute assessed the elemental composition of the real painting. The conservators are so adept at relating elemental components with pigments used to mix paint, they not only recreate what’s on the surface, they determine what’s underneath it.

“Our x-ray radiography reveals that there was a painting underneath the painting,” Carson explains. “And if we turn \[the results\] upside down, you’ll see there’s another face.”

The replica painting was made for a high-powered x-ray at Stanford University. They wanted to test the copy first to see if the process damaged it before running the test on the actual Rembrandt.

Unfortunately, much like master painters, Getty scientists find themselves caught in the creative vortex of time. In this case, the Getty found that by the time they’d prepared the duplicate for its fated Stanford test, a newer, better technology had come to market. In the end, the preliminary test wasn’t necessary, leaving the impersonation without a cause.

Of artist Stephen Kaltenbach’s numerous works—postmodern sculptures, extra large, dual perspective paintings—his conceptualist work carries a weighty potential, a humorous “spring constant.” In a letter to NASA, in anticipation of Apollo 11, Kaltenbach pithily explains his sculpture, a gift to Neil Armstrong. It was of a boot with a relief of a bare foot underneath. He hoped America might leave a footprint on the moon, of an astronaut who’d forgotten to put on one of his boots.

Meanwhile, the technician holds her _contrapposto_ pose for minutes at a time, nodding down to mark her sheet, nodding up to observe. Wearing de facto university lab goggles and a white apron, one might ask, is a quarantine in effect? Seeing my concern, Szafran confides, “we’ve taken out all the oxygen \[from the bagged painting\] and replaced it with nitrogen. If there’s anything inside, they’re not going to survive this treatment.” Given that even invaluable works of art are prone to infestation, one might sigh, in relief that anything resists entropy, time. “This is standard practice,” assures Szafran. “This is unlikely but there were certain signs that made us suspicious. This is a precaution more than anything else. We’ll feel better at the end.”

In the analysis of a painting based on the prevalence of specific compounds (in the case of this Tuscan altarpiece, gold factored in heavily), conservators can assert where it was likely to have been painted, what conditions it weathered, possibly even what historical events it lived through.

“Some artists have better technique than others,” Szafran says. “If you go back to the 16th century or even earlier, the first thing these artists had to do was learn how to make paint.” This consistency in pigmentation adds substance to the narrative of a painting. Because today’s mass-produced acrylics are less than a century old, science can only trust models to predict long-term patterns of deterioration.

“In the 20th century, they started using house paint. it’s interesting but it’s hard to take care of.” Szafran sighs. So what happens when today’s artists use blood, feces, vomit, and/or roadkill to fully express man’s eternal struggles?

“We call these ‘inherent vices,’” Szafran explains coolly. “And yes, curators and representatives have to ask artists things like, ‘when the cigarette butt falls off, how would you like us to deal with that?” But whom does the curator ask when the artist is dead? “Once they die it becomes more difficult. It’s generated a lot of conversation, whole conferences are dedicated to it.”

Today’s painters are likely to swipe a smartphone or flip open a laptop to order blue paint. They won’t dodge the radial needles of a yucca bush in pursuit of dried juniper berries. There’s nothing to dominate. Nature’s no longer natural. “\[Early\] artists were very conscious of making a painting that would last.”

The way Szafran sees it; today’s artists aren’t concerned with longevity. What satisfaction is there for death, waiting, like the defunct Rembrandt replica, somewhere in a Getty basement, when met with today’s artist? “I’ve been waiting for you,” death might say. “Take me,” the artist might say.

As for the next generation of Szafrans and Carsons, historians of art—proliferates of content and documentation—what will their work entail? Could you imagine finding a shattered silicate from beneath the rubble of Madison Square Garden in 2200? Would you work backwards through ones and zeroes, beginning with a database of genetic coding, to try and figure the exact second that Kanye, if it was Kanye, smashed his phone in a fit of rage?

Perhaps Getty spoke his own truth when he said every history is nothing more than a colorful recreation. The Getty is the finest source of recreation of the past, and joy of its enablers echoes through its longest, most dampened, most secure hallways.

_Photographer: [William Converse-Richter](http://william-converserichter-gybc.squarespace.com/)._

[](#)[](#)

The Getty Center: Made In The Image And Likeness Of Self

The Getty Center, commenced in 1984, and opened in 1997, now possesses more viewing options than Netflix, and offers more rewarding search results than Google—but underneath its quiet campus, a clandestine network of art historians and research scientists facilitate groundbreaking interrogation, working to answer millennium-old questions of authenticity, materiality, circumstance, and transition—in one word, history— which might write over the fables once agreed upon.

“Sometimes we have to use our imagination a bit when investigating historical events.” – J. Paul Getty

Upon Jean Paul Getty’s death in 1976, to the surprise of Art and family, he left $700 million—much of his estate—to a group of trustees. The Getty Trust, as it was ordained, was to use this money for the “Diffusion of Art and General Knowledge.” Clarifying the terms, and releasing these funds, proved an ontologically supreme task—the trust surpassed $1 billion before finally being settled and put to use. In 1982, the Getty Research Institute opened atop a browning chaparral bluff in the Brentwood neighborhood of the Santa Monica Mountains in Los Angeles.

In unanimity, the campus today hosts the Getty Research Institute, the Getty Conservation Institute, one of two Getty Museum locations (the second is the Getty Villa, in Malibu), and the Getty Trust: now the highest valued arts research trust in the world at $6.7 billion.

Gazing West from the central courtyard, ten miles inland from the coast, one might scan the houses lining numerous saddleback drives winding through hill after hill leading towards the glimmering blue Pacific Ocean. The rare vestige of virgin L.A. landscape is said to have reminded Getty Center architect Richard Meier of Tuscan hillsides. Meier proposed a design relying heavily on polished travertine, but it didn’t appeal to Brentwood trustees. The architect countered with a suggestion that the entire campus use rough travertine, raw with exposed fossils. The trustees were satisfied.

Outside, well beyond the rumbling din of the 405 Freeway, Meier’s fibrous rock surfaces attenuate the California sun, imposing a soft, natural light. Stone surfaces, steel framing, and glass facades; the entire campus is essentially made from three materials.

Through a glass entryway, past a curved reception desk, staff members exchange Chinese currency for American dollars. Through carpeted hallways, as one scuffles past a series of doors, security guards attend to monitors and radios, checking that every entrant carries proper clearance. One is reminded of the contemporary mega church—a sense of intense serenity wrapped delicately in a silencing religiosity. A left turn leads towards the Getty Research Institute’s Special Collections.

Here, concentric shelves interspersed with private desks lead to a circle of travertine that sits directly beneath a glass oculus. It basks in a thick beam of golden sunlight at one in the afternoon on the Summer Solstice. On any given day a respected architectural writer (and UCLA professor) in his late 70s might be found on a nearby cushioned seat, reclining in slumber, an aged baseball cap draped over his pursed lips.

Inside a multi-room studio/lab facility of the Getty Conservation Institute, a scientist jots down vitals on a clipboard. Her eyes move from the sheets resting on her non-writing arm, to an elevated, square operating table. Above the setup, a series of tubes hang down and attach to a sealed bag. Below, tilted circular gauges display pressure and temperature. Flat inside the bubble, lies the central panel of a 15th C. altarpiece of medium size, roughly four by eight feet, tempera and gold on wood. The painting is that of Giovanni di Paolo, of Siena, Tuscany. As you pass by, please don’t break out your selfie-stick.

“Oh, you’re photographing, but you can’t publish that because it doesn't belong to us,” says conservator Yvonne Szafran. Stern and congenial, she’s spectacled, stylishly academic. She wears light-tan low-cut riding boots. “I guess if you don’t get any paintings, that’s okay.”

One time the Getty allowed an innocent photo to appear on a blog, explains Szafran. “Someone zoomed in on a high- res photo and caught something they weren’t supposed to see.” Szafran laughs as she chides, projecting the authority and intelligence suitable for a real-life archaeology journey. Though her pursuit for historical comprehension involves less exotic scenery and more routine lab work.

Perpendicular to Szafran’s workspace, a tempera, gold, and ink parchment rests on an easel. It’s a lower portion of di Paolo’s altarpiece. An adjacent easel holds a sheet with four even squares, each a variation of some amorphous shape. Like ghostly blue-grey negatives, they resemble enriched x-rays. Warholian ephemera? Perhaps not.

These are test results contextualizing the history of di Paolo’s altarpiece. Szafran and her colleagues have spent the past months analyzing three different di Paolo compositions. Over 450 years ago, these parchments and wood panels might have endured a sanitary, serene existence within a Sienese church. through stained glass windows, one might have turned from Di Paolo’s secular artwork and caught sweeping hillsides, curving steeply down into the Mediterranean coast, filtered red and blue through the stained glass panels. It’s a startlingly familiar overlap, one Mediterranean climate to the next.

Back in the conservatory, about 50 feet north of Szafran’s desk and through a long, quiet, open office space, one finds a cream-colored door. It opens into a shielded chamber that feels like a dated x-ray room or the front desk of a public school library. Here, a team of international scientists and historians conduct x-rays as well as infrared reflectography. The ceiling hangs over 20 feet overhead to give clearance for the arm of the x-ray tube. Szafran jests, “It’s a bit like a medical x-ray, but our patients don’t move.” So why would anyone examine a painting in such detail? Fraud for one, something J. Paul Getty dealt with throughout his lifetime as an art collector. There’s something ancient, divinely comedic, in imagining a tale of a rich fool. A man of great means and limited understanding meets a man of limited means and wider knowledge. The ending writes itself.

“It’s like detective work. We want to know everything we can about a painting before we begin to study it,” Szafran says. Having spent decades in the field, she’s seen the technological leaps. Leaving the x-ray chamber, “old technology” as Szafran calls it, since scientists have been using this method since around 1900. Outside, a short hallway leads to an intimidating metal door.

“That’s where we conduct electron microscopy and hyperspectrum analysis.” After a half hour with Szafran, it begins to feel normal for 500-year old paintings to perch unframed on sturdy easels, while equipment that might have helped launch humans into outer space waits for further command.

Assuming proper security clearance, one might pass through another security door to find research lab associate David Carson. He works with the Science department, analyzing inorganic building materials.

“An electron microscope works like a old black and white TV,” he says with a scientific, confident tone. “Each pixel gives you a different greyscale intensity, the different shades become a black and white image. You’re limited on the wavelength of light, and that’s why you use electrons.” Using elemental analysis, Carson and his team can determine the concentration of iron, lead, or any other relevant element. He reaches for a small cubic sample on his desk, about two inches on each side.

“This is a piece from a building in Brazil that was destroyed. A \[Getty Research Institute\] scholar wanted to understand the mortar. As we move from the white mortar, to calcium carbonate and sand, you get into the paint layers—zinc and barium, moves to iron, and then we get titanium dioxide, modern pigments. we can figure out every time this building was painted since it was constructed.”

Speaking naïvely, Carson’s lab feels aesthetic, like a retrofitted set from Barbarella—heat chambers with round rotary windows, vacuum chambers with sliding glass doors—but Carson isn’t representing an ideal.

“We don’t just take samples to take samples. It depends on the question the scholar is asking.” That’s not to say that Carson’s work entails any less imagination. In a recessed chamber, one can find an easel, and what appears to be a Rembrandt oil painting, “Old Man in Military Costume.” “This is not a real painting. This is a mockup,” announces Carson. “This was made by an intern.”

After importing a new technology, the Getty Institute assessed the elemental composition of the real painting. The conservators are so adept at relating elemental components with pigments used to mix paint, they not only recreate what’s on the surface, they determine what’s underneath it.

“Our x-ray radiography reveals that there was a painting underneath the painting,” Carson explains. “And if we turn \[the results\] upside down, you’ll see there’s another face.”

The replica painting was made for a high-powered x-ray at Stanford University. They wanted to test the copy first to see if the process damaged it before running the test on the actual Rembrandt.

Unfortunately, much like master painters, Getty scientists find themselves caught in the creative vortex of time. In this case, the Getty found that by the time they’d prepared the duplicate for its fated Stanford test, a newer, better technology had come to market. In the end, the preliminary test wasn’t necessary, leaving the impersonation without a cause.

Of artist Stephen Kaltenbach’s numerous works—postmodern sculptures, extra large, dual perspective paintings—his conceptualist work carries a weighty potential, a humorous “spring constant.” In a letter to NASA, in anticipation of Apollo 11, Kaltenbach pithily explains his sculpture, a gift to Neil Armstrong. It was of a boot with a relief of a bare foot underneath. He hoped America might leave a footprint on the moon, of an astronaut who’d forgotten to put on one of his boots.

Meanwhile, the technician holds her _contrapposto_ pose for minutes at a time, nodding down to mark her sheet, nodding up to observe. Wearing de facto university lab goggles and a white apron, one might ask, is a quarantine in effect? Seeing my concern, Szafran confides, “we’ve taken out all the oxygen \[from the bagged painting\] and replaced it with nitrogen. If there’s anything inside, they’re not going to survive this treatment.” Given that even invaluable works of art are prone to infestation, one might sigh, in relief that anything resists entropy, time. “This is standard practice,” assures Szafran. “This is unlikely but there were certain signs that made us suspicious. This is a precaution more than anything else. We’ll feel better at the end.”

In the analysis of a painting based on the prevalence of specific compounds (in the case of this Tuscan altarpiece, gold factored in heavily), conservators can assert where it was likely to have been painted, what conditions it weathered, possibly even what historical events it lived through.

“Some artists have better technique than others,” Szafran says. “If you go back to the 16th century or even earlier, the first thing these artists had to do was learn how to make paint.” This consistency in pigmentation adds substance to the narrative of a painting. Because today’s mass-produced acrylics are less than a century old, science can only trust models to predict long-term patterns of deterioration.

“In the 20th century, they started using house paint. it’s interesting but it’s hard to take care of.” Szafran sighs. So what happens when today’s artists use blood, feces, vomit, and/or roadkill to fully express man’s eternal struggles?

“We call these ‘inherent vices,’” Szafran explains coolly. “And yes, curators and representatives have to ask artists things like, ‘when the cigarette butt falls off, how would you like us to deal with that?” But whom does the curator ask when the artist is dead? “Once they die it becomes more difficult. It’s generated a lot of conversation, whole conferences are dedicated to it.”

Today’s painters are likely to swipe a smartphone or flip open a laptop to order blue paint. They won’t dodge the radial needles of a yucca bush in pursuit of dried juniper berries. There’s nothing to dominate. Nature’s no longer natural. “\[Early\] artists were very conscious of making a painting that would last.”

The way Szafran sees it; today’s artists aren’t concerned with longevity. What satisfaction is there for death, waiting, like the defunct Rembrandt replica, somewhere in a Getty basement, when met with today’s artist? “I’ve been waiting for you,” death might say. “Take me,” the artist might say.

As for the next generation of Szafrans and Carsons, historians of art—proliferates of content and documentation—what will their work entail? Could you imagine finding a shattered silicate from beneath the rubble of Madison Square Garden in 2200? Would you work backwards through ones and zeroes, beginning with a database of genetic coding, to try and figure the exact second that Kanye, if it was Kanye, smashed his phone in a fit of rage?

Perhaps Getty spoke his own truth when he said every history is nothing more than a colorful recreation. The Getty is the finest source of recreation of the past, and joy of its enablers echoes through its longest, most dampened, most secure hallways.

_Photographer: [William Converse-Richter](http://william-converserichter-gybc.squarespace.com/)._

.jpg)