F L A U N T

We have all, at one point or another, found our native tongue a faulty instrument when expressing matters of the heart. Feelings of sadness and sorrow can sometimes resound as a flagrant downplay. Our “I love yous” may hit the ear like a passive overture in what feels like a symphony of affection. So we turn to music, which inexplicably and invariably answers what syllables and syntax cannot. It is this chasm between emotion and its expression that concert pianist Lang Lang has made it his art to mend.

“This is what you call a universal language,” Lang Lang tells me over the phone from the backstage of Edinburgh’s Usher Hall, where he is poised to perform in two hours on an early stop on his near year-long world tour. “Even an alien, who doesn’t know anything about the earth, would understand our emotions and messages when they listen to an opera or a piano solo.”

And Lang Lang’s other-worldly praxis certainly translates in action. From playing the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games Opening Ceremony to the recent Notre-Dame reopening, collaborating with Pharrell Williams to Andrea Bocelli, or with the world’s top orchestras, the Shenyang, China native has cemented himself as the master of his chosen vernacular. It’s one that all can understand. But despite having performed for global dignitaries—Queen Elizabeth II, Barack Obama, UN Secretary-Generals—Lang Lang’s most intimately held performance is with his visit to Tanzania in 2004 to perform for children as UNICEF’s Goodwill Ambassador. “The joy I saw from the faces of these children…without knowing each other at all, without speaking the same language—you become very good friends after just two or three pieces.”

The virtuoso’s passion for humanity and interrelation is what underpins the mission behind Lang Lang’s Piano Book 2—the sequel to Piano Book, a collection of pieces accompanied by mastered recordings released initially on World Piano Day in 2019. Both collections include what Lang Lang calls “masterpieces in miniature,” which seek to invigorate the innate passion of classical music to the younger generation. On paper, they’re pieces that well-trained musicians have become weary of, technical exercises that pubescent pianists dread. “Some kids get so mad practicing Burgmüller, you know,” Lang Lang says. To any good classical musician, Debussy’s Clair de Lune and Czerny’s drills can only be rendered so many times before they morph into a mere tragedy of Muzak. A great musician, however, can find inspiration in any score. “It’s essential. We have to do something to inspire the kids to practice with more passion.”

In spirit, Lang Lang’s assemblage is a love letter to the sheet music behind all fundamental classical education, including his own. “When I was a kid, there were many great pieces. But there were no great recordings,” Lang Lang says. “There’s a lot of churning etudes, but you don’t really know how to do it.” The how comes not from the sheet music itself. It’s found between the lines. “You can go crazy, but not that crazy,” Lang Lang muses on how he approaches the interpretation of a new work. “You can be creative, but you really have to respect [the piece].”

For the official Steinway Artist, creativity is shaped by the process of knowing, by the duty of the classics in every sense of the word. Case in point? Acting out Shakespeare plays for up to three hours a night with one of his mentors when he first arrived to the States—his first introduction to Western learning. “It gave me a tremendous understanding of Western culture. Real inspiration. Now, I can characterize each note like a play.”

But alas, as is the case with Bach’s or Beethoven’s posthumous fame, no one is impervious to the unpredictability of cultural affect. How do you make the foundation of classical music resonate with contemporary youth, riddled by a poor attention economy, when the genre is now buried in the background of video games, and mere accompaniments to visual media? Classical music, now more than ever, is unconsciously heard, but seldom energetically felt.

Lang Lang has some ideas. In memory of its predecessor, Piano Book 2 includes the canon works: Beethoven’s Turkish March, Chopin’s Fantaisie-Impromptu. The challenge this time around comes from curating arrangements from sensationalized OSTs and pop songs where classical elements are sincerely infused. Lang Lang’s collection takes this on by becoming both an educator of its creator’s own past and a pupil of the present itself.

Consider “Black Myth: Wukong Main Theme” for example. It’s the titular video game track inspired by popular Chinese soap opera Journey to the West—one of Lang Lang’s own fondly carried themes. But stronger than his nostalgia is his fascination with the melody’s own journey to the West. “It’s unfortunate the soap was never made popular in the West, so it was very interesting how they used the 80s TV melody to honor the original in the new game,” Lang Lang reflects. The tune’s belated arrival is much akin to the barriers Lang Lang faced in his early career. “Forty years ago, there weren’t enough Asian players.” As he sees it, those barriers are now of the past, which he can rummage through for relics worth keeping.

Lang Lang’s destination still, 40 years in, is the journey. It’s about the adventure of travel, of people, of new foods. It’s about picking up a sheet of paper, becoming a historian of its fibers, befriending its maker, folding it into a crane, and figuring out how to make it fly. Over, and over, and over again. For him, the answer to how passion is retained is simple. “You just keep playing.”

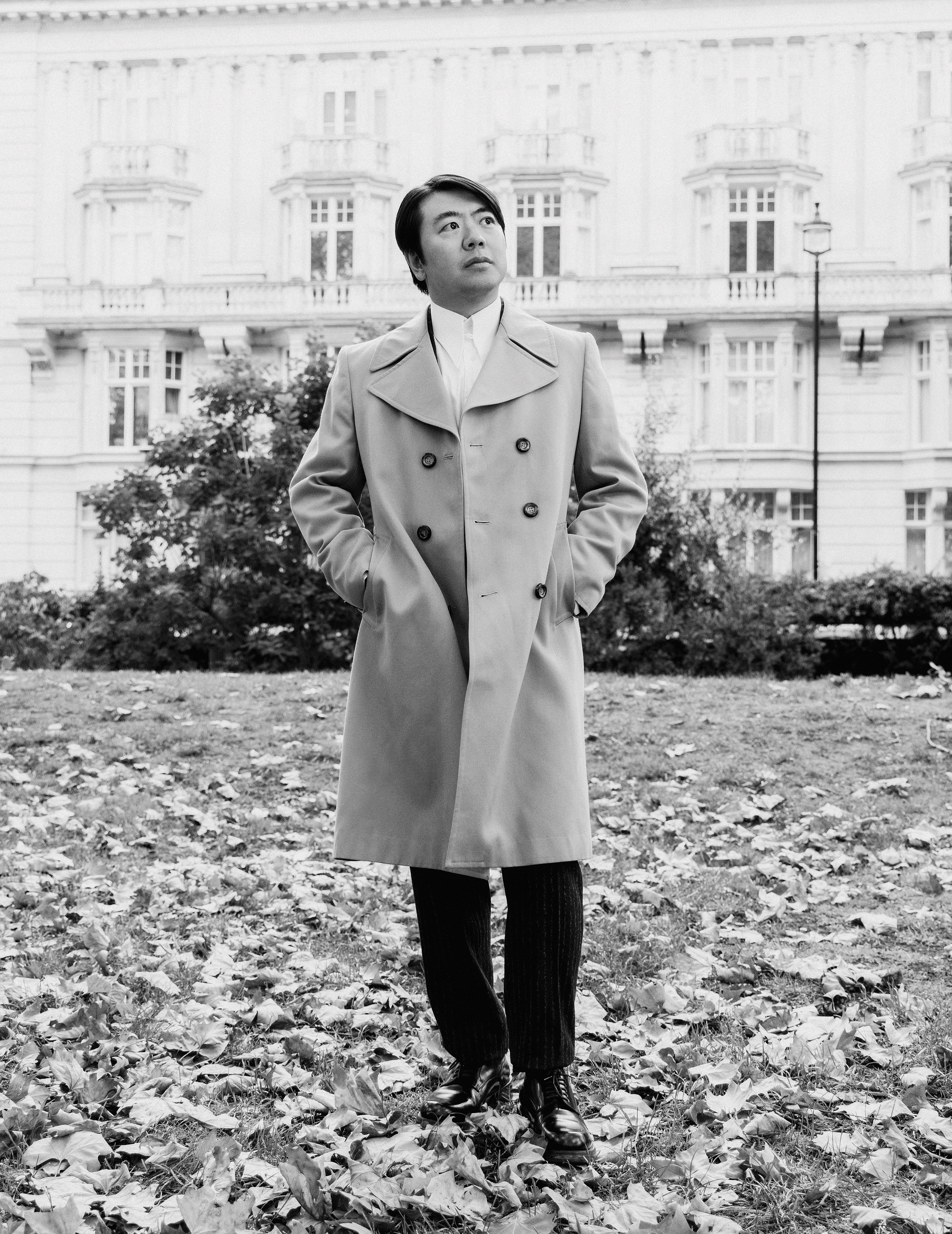

Photographed by Jack Beere

Styled by Harvey Turner

Written by Julia Fu

Grooming: Darren Agyei-Dua

Photo Assistant: Ella Knez

Location: Wigmore Hall