F L A U N T

Derek Cianfrance’s films feel like handwritten letters sent to the future–emotional dispatches that explore legacy, spanning generations. From the toxic love of Blue Valentine to the generational sins of The Place Beyond the Pines, and later the sprawling ache of I Know This Much Is True, his oeuvre revolves around a central concern: What do we pass down to one another, willingly or not? Speaking to Cianfrance about his earlier work, he explains, “I made all those films during the first 18 years of my children’s lives. I was really affected by becoming a father. I started to obsess about what I was going to pass on to these children that were so pure and so open.”

Each of his films explores that question differently. While he started writing Blue Valentine after his parents’ divorce, it eventually became more personal. “What Blue Valentine became to me was a cautionary tale,” he says. “It was a projected fear of my life, my relationships moving forward.” If Valentine is a warning about love’s imperfection and impermanence, Pines serves as a darker genealogical sequel about masculinity. “My father had a temper, and my grandfather had a temper, and I had a temper,” he admits. “I wanted my son to come into this world and not have that thing passed on to him.”

With I Know This Much Is True, he reached what felt like a satisfying conclusion: “When I got to the end of it...I felt like I could confront everything that I could confront on that topic.” Looking for his next feature, Cianfrance says, “I felt like I didn’t want to repeat myself. I wanted to be free with a movie, free myself up, not play the same song again.”

Enter Roofman—through the ceiling, Tom Cruise M:I-1 style. The comedy is based on a true story about notoriously polite criminal Jeffrey Allen Manchester—a former US Army reservist who robbed numerous buildings by drilling through their roofs in the late 1990s, broke out of prison by riding beneath a truck, and lived behind a bike rack in a Toys “R” Us in Charlotte, North Carolina for six months, where he fell in love, joined a church group, and quickly became integrated with the community. Cianfrance came across Manchester’s story and found himself inspired, so the director got in contact with Manchester (now a prisoner in North Carolina), and started speaking to him 3-4 times a week.

“Jeffrey is incredibly charismatic. He’s a real storyteller,” Cianfrance says. “I would almost say maybe he’s a tall-teller, because the stories that he tells you about what he did seem almost unbelievable. But then you go and read the police report, and you find out—no, he did these things.” Like, for example, the fact that Manchester politely offered his hostages warm coats before locking them in fridges.

“He’s a very intelligent guy, and he’s also made some of the stupidest choices that you could make,” Cianfrance asserts. “There’s a Robin Hood quality to him, because he was stealing from stores and giving the church toy drives. His intentions were always kind of pure. It’s just the way he went about getting the things that he wanted was wrong.” Discussing a recent call with Manchester, Cianfrance shares, “His mom had just passed away, and he told me one of the last things him and his mom did was have a good laugh because they read a tagline on the poster: ‘Based on actual events and terrible decisions.’”

While the outrageous headlines might have reeled him in, the director found the emotional “north star” for Roofman in Manchester’s longing to participate in the culture of the mall he was trapped inside. “He didn’t judge that society. He was trying to be a part of it,” Cianfrance says. “He wanted, more than anything, to have a family and take them on picnics, go shopping, and give them gifts. He was kind of like a capitalist junkie who just loved everything that had to do with suburban society.”

Growing up in the suburbs of Denver, Cianfrance feels a fondness for the Roofman setting. “I was like the fastest checker in the history of all Colorado Walmarts, and I was the menswear employee of the month one month,” he laughs. “I grew up in those big box stores, and never really saw [the suburbs] on the screen…[They] always feel a little judged. Everyone from my family came from those places, and I didn’t have any judgment towards it.”

Shooting on-location at the same, now-abandoned Toys “R” Us where Manchester hid out in Charlotte, Cianfrance was able to cast many of the real-life characters from the story, including the prison truck driver who unwittingly drove Manchester out of prison. The director explains how the grassroots production felt like a return to his roots. “My whole life as a filmmaker, since I was six years old and working on cassette tape, I was always making home movies. Cianfrance says, “By taking this down to Charlotte, by making it a movie about a person who wants to be a part of a home. I used all the people that were in the real story. It just felt like we were all making a home movie.”

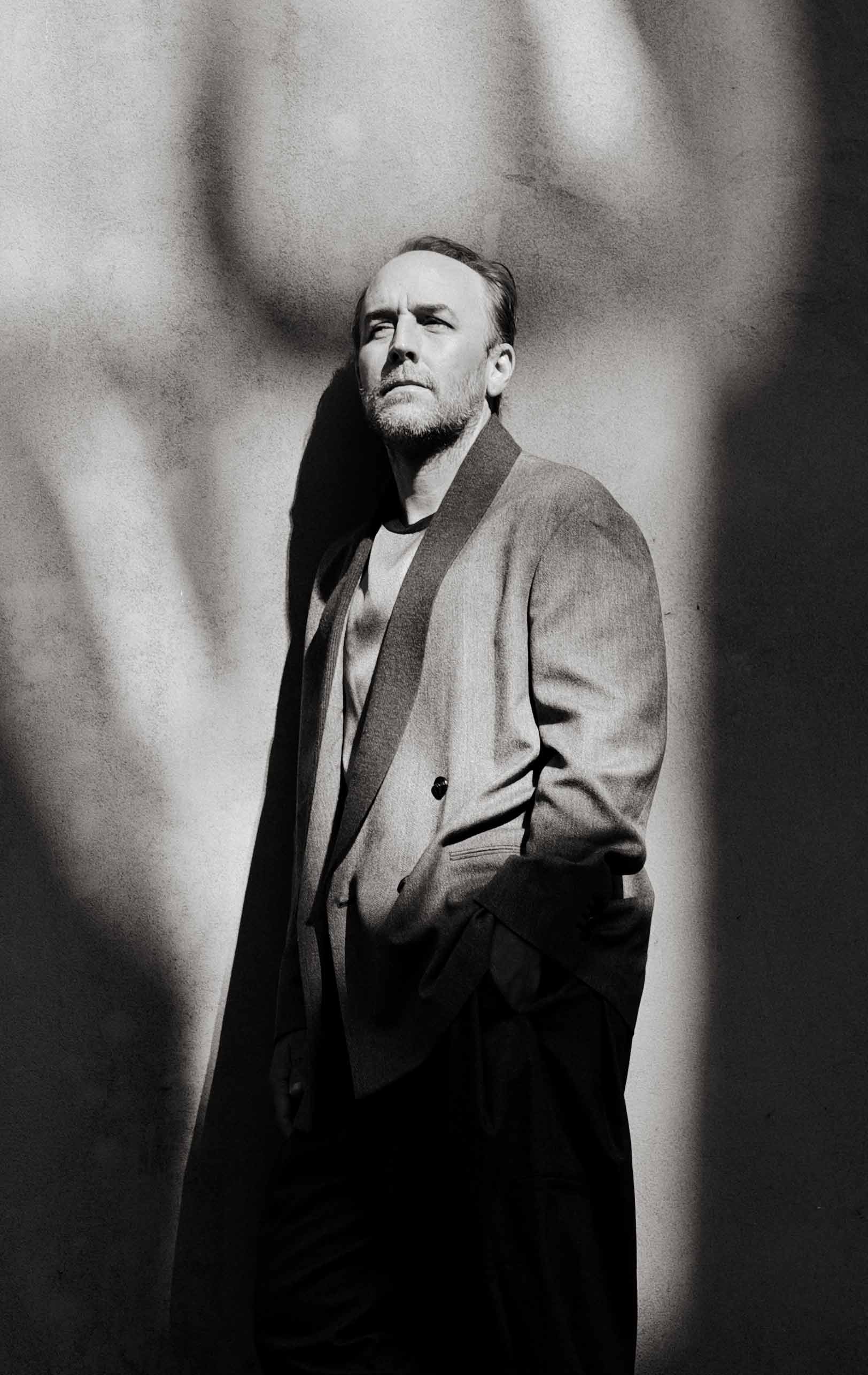

Photographed by Mynxii White

Styled by John Tan

Written By Oliver Heffron

Grooming: Deborah Altizio using L'Oreal Professional Air Light Pro