F L A U N T

Sixty-five years ago, scientists Gregory Pincus and John Rock, with aid from Planned Parenthood, made medical history when they developed the first clinical birth control pill, formally approved by the Federal Drug Administration in 1960—revolutionizing the concept of oral contraception as an effective method of preventing pregnancy. Within two years of its initial distribution, 1.2 million American women had begun taking the birth control pill. Today, over 15 million women rely on it as a daily measure against gestation.

But while studies note its 99% success rate in preventing pregnancies, its ingestion also comes with a surfeit of unpleasant side effects such as breakthrough bleeding, headaches, nausea and breast tenderness. Additionally, the pill is known for affecting things like mood, acne, sex drive and hair thinning, while more serious health risks include blood clots, heart attacks, strokes and an increased risk of certain cancers—leaving women weary of its overall safety and many in desperate search for more natural, non-hormonal alternatives.

And although new forms of contraception have intermittently been introduced throughout the years—namely intrauterine devices and implants, as well as the rise of female sterilization—one thing remains fundamental to each of these various mechanisms’ effectiveness: female ovulation. You see, in all the decades of both gynecological and fertility research, the discussion of male birth control as a viable counter measure has only recently begun to take center stage.

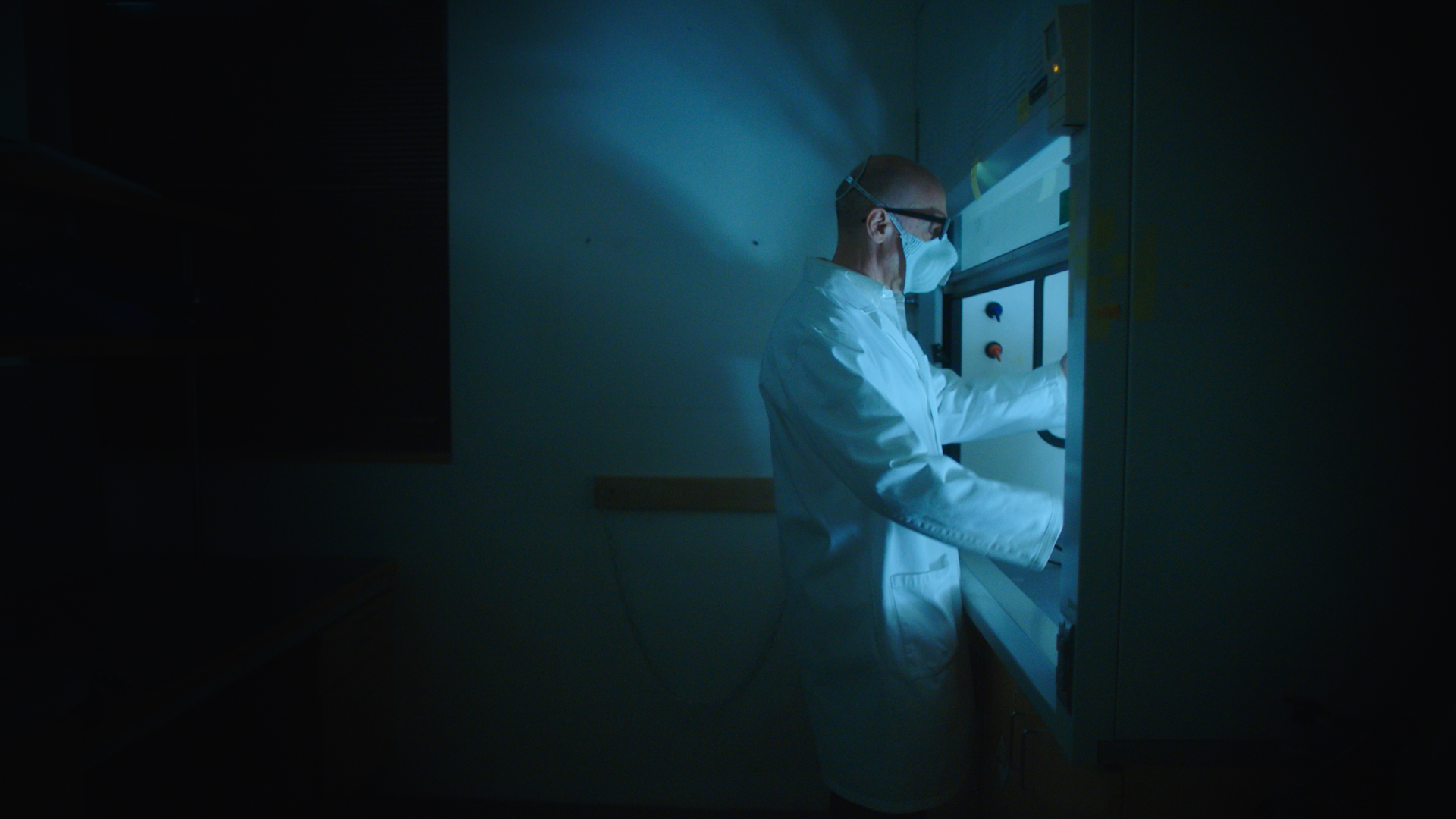

It’s Different For Girls, a new documentary short film from British journalist turned filmmaker Billie JD Porter, which premiered at this year’s Hot Docs Festival in Toronto, explores the juvenility of male contraception, examining misogyny as a root cause for its prolonged arrival. Spotlighting two main forms of male contraception presently deep in the research and development phase—a novel shoulder gel and a hormone-free oral pill, both of which suppress sperm production in men—It’s Different For Girls evaluates the weight of contraceptive responsibility, prompting the question whether the lack of male birth control is a result of scientific roadblock or systemic gender bias.

FLAUNT spoke with Porter to learn more about what inspired her to make male contraception the cornerstone of her documentary debut, her transition from journalism to filmmaking, how willing she thinks men will be to realistically take birth control, and what she hopes viewers will take away from the comprehensive analysis.

What drew you to hone in on male birth control? Is there any incident in particular that initially inspired It’s Different For Girls?

My initial interest in the topic was from a very personal place, related to my own experiences with contraception. I’d been having a bad time with my IUD, and so ended up switching to a different brand, only to suffer even worse side effects with the new one. I was feeling so fatigued by the entire process—weighing up whether to come off birth control completely, or try a new pill formulation. Myself and my partner at the time had briefly discussed the possibility of him getting a vasectomy in passing, but the conversation didn’t really go anywhere. The very idea of a man even considering something like that seems drastic or extreme in our society, because women have pretty much always shouldered this burden, historically. When I really confronted that reality, amidst what I was having to sacrifice—both in terms of my mood and physical side effects—I was motivated to learn more about how we’d arrived here, culturally. When I began researching, and found out how far along these various potential new methods were for men, I was completely stunned. Then, when I actually started speaking to all of the incredible people who have dedicated their lives to this space, I knew there was a film here.

I thought you interviewed an interesting range of men who have participated in the trial runs thus far. All of them come from various cultural and religious backgrounds which lend in part to them perceiving their masculinity differently, but were ultimately all drawn to male contraception for one reason or another. Tell me about what you learned from speaking with your subjects.

It was important to me that the film included a wide range of perspectives, to communicate the broad demand for these new products. I think audiences have been really shocked to see a Mormon, pro-life couple participating in the trials, and so eager to be a part of something which many would still view as pretty radical. I was ultimately very reassured by the willingness of men to step in, largely because they’ve witnessed first-hand the toll that birth control can take on their partners’ bodies and minds.

How open do you think men will realistically be to taking male birth control?

I’m optimistic. Various market research studies suggest that there’s a very real desire for new contraceptive methods. Since the overturning of Roe vs. Wade there’s also been a huge spike in vasectomy demand and people signing up for new birth control trials. There’s also, of course, a whole market of people outside of this very heteronormative framework who would benefit from these products becoming accessible. The language around these new methods doesn’t yet reflect the reality that gender identity doesn’t always necessarily align with reproductive organs, but whether female, male, or nonbinary; cisgender or transgender; birth control has the potential to be the ultimate tool for liberation. Historically though, it’s sometimes done the exact opposite, leaving people feeling trapped, exploited or misunderstood. With the film, I’m ultimately trying to convey the need for wider overall access to a better range of methods, for everyone.

What are the parallels between journalism and documentary filmmaking? How did one inform the other for you?

I’ve always worked in video or television parallel with writing, but up until this project I’ve never had the full creative control to develop a whole visual world or score from scratch, while remaining fully behind the camera. With writing, you are always subject to an editor’s final pass, which can sometimes ultimately change the tone and cadence of what you’re trying to say, if you’re not lucky. It’s the same in television, with commissioner feedback. Doing It’s Different For Girls so independently, meant I wasn’t having to get notes from any higher ups. It was definitely a collaborative process, but it feels completely my own, and I think that’s really given me a greater sense of fulfillment and pride than I’ve ever experienced before in my career, regardless of the medium.

In terms of style and tone, did you have any artistic influences that helped shape the storytelling of It’s Different For Girls?

I worked with two incredible editors on the project—Mimi Wilcox and Tyler Pharo. Mimi and I are big fans of a documentary called Mike Wallace Is Here, which is completely comprised of archival footage, populating in multiple different split screen compositions. We definitely took some influence there as we built out some of our own historical archival segments, and then we liked the result so much that we continued to bring some splitscreen moments into the interview portions too. I really wanted to strike a unique visual language across the film, with how we incorporated text and color—it all lives in a pretty wry pink and blue palette, nodding to the subject matter. I also collaborated with an incredible video artist, Jennifer Juniper Stratford, on a series of spoof pharmaceutical ads. I had a really specific vision for those scenes, which I think some people had initially raised their eyebrows at when I tried to describe it, and she just got it immediately. It was probably one of the most fun days across the whole production. Her whole back catalogue of work and dedication to such a specific aesthetic is really inspiring to me.

How do you hope audiences interact with the work?

I hope that amongst couples where one partner is shouldering the burden of taking birth control, that there’s a deeper understanding of the potential implications for that person. Right now, men may not be able to step in and offer to take that responsibility entirely, but they can certainly do more to empathize with the position that women are in. Outside of this, I hope there’s less stigma and fear broadly around the idea of men taking birth control. One of the best ways for us to speed up the process of being able to access these products is by being vocal about the demand. Having spoken to a lot of audience members after our screenings, I think the film is doing a pretty good job of showing how empowering it could be for them to have an option available to them.

With the overturning of Roe v. Wade and current Trump administration in office, this film comes at an especially potent time. What impact do you think the introduction of male birth control would have on our medical infrastructure as it stands now?

Right now there is no regulatory process in place to approve a new male birth control option, because so far no potential product has made it to Phase 3 trials. Right now we’re in completely uncharted territory, because it looks like that’s finally likely to happen, with a product called NES/T gel. So far the results from the trials have exceeded everyone’s expectations, and in order to push things forward, the FDA will need to put brand new guidelines into action. Obviously the FDA has been subject to enormous cuts under the current administration, and is heavily influenced by the government’s stances on reproduction and healthcare more broadly, so there’s a lot of uncertainty. It really feels like we’re on the brink of a truly historic moment for culture and society, but unsurprisingly, there’s a hell of a lot of bureaucracy and red tape.

What's next for you?

It’s Different For Girls is still on its festival run, so I still definitely have one foot in that for now, but I have started development on a few new documentary projects. One of them is pretty historical and the other is about an online movement, so it’s been nice to have that range during the research phase.