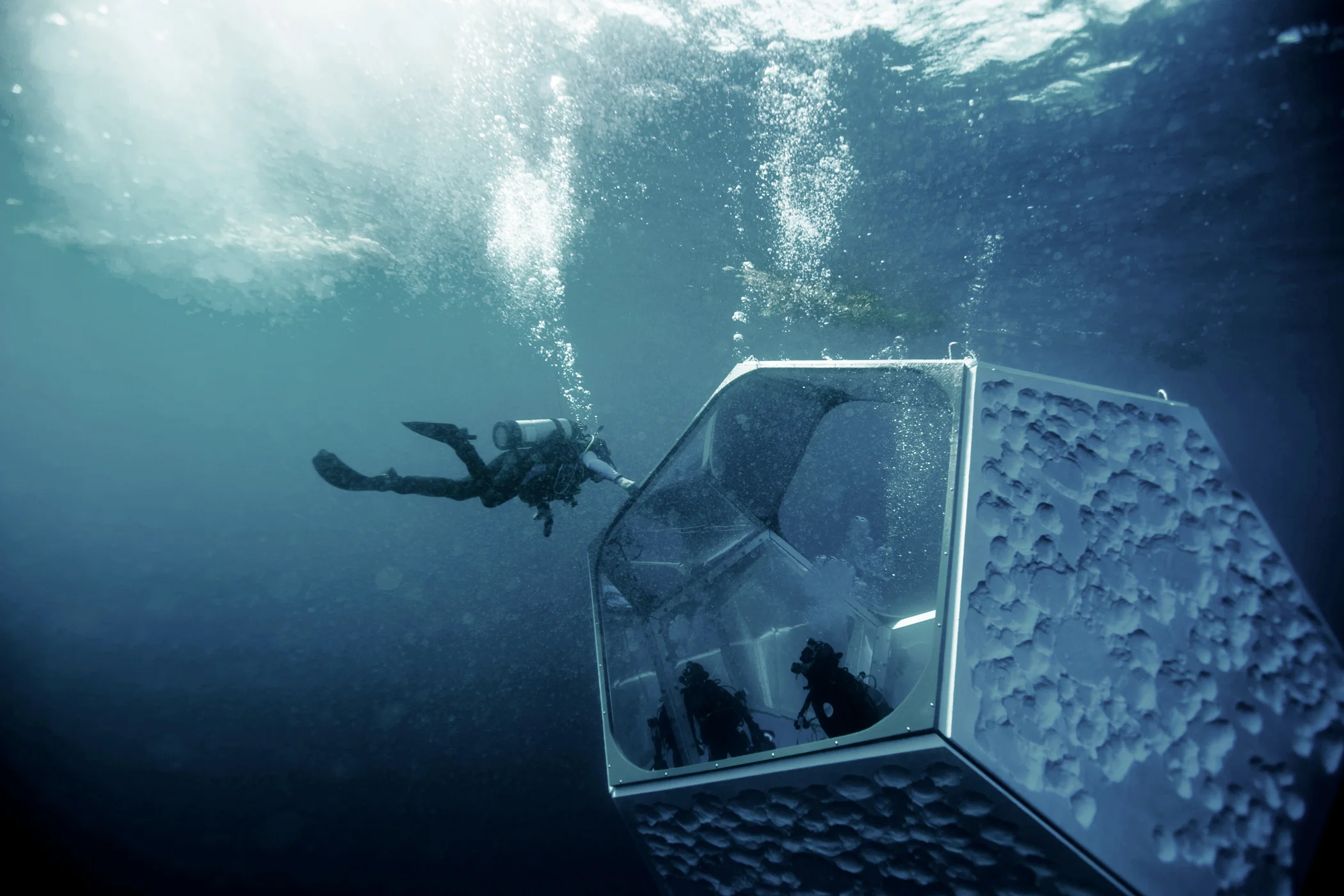

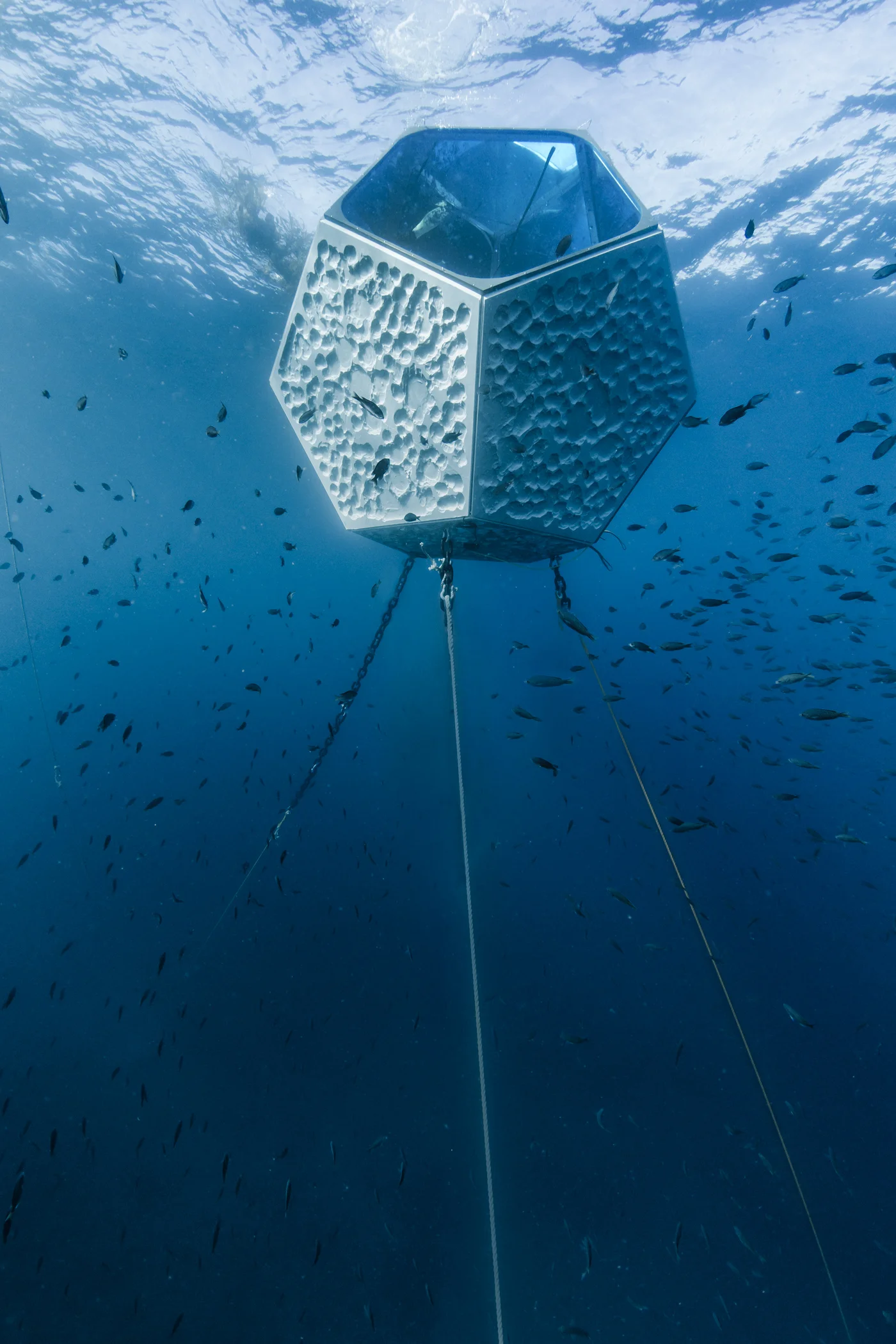

Doug Aitken. Installation View, “Underwater Pavilions” (2016). Courtesy The Artist And Parley For The Oceans.

Doug Aitken. Installation View, “Underwater Pavilions” (2016). Courtesy The Artist And Parley For The Oceans.

Doug Aitken. Installation View, “Underwater Pavilions” (2016). Courtesy The Artist And Parley For The Oceans.

Doug Aitken. Installation View, “Underwater Pavilions” (2016). Courtesy The Artist And Parley For The Oceans.

Doug Aitken. Installation View, “Underwater Pavilions” (2016). Courtesy The Artist And Parley For The Oceans.

Doug Aitken. Installation View, “Underwater Pavilions” (2016). Courtesy The Artist And Parley For The Oceans.

Doug Aitken. Installation View, “Underwater Pavilions” (2016). Courtesy The Artist And Parley For The Oceans.

[](#)[](#)

Doug Aitken

Our correspondent dives in for a look at artist Doug Aitken's new underwater sculptures

The human relationship with what lies beneath the ocean is, for most of us, one of opposition—dry:wet, visible:invisible, warm:cold, safe:deadly—we are surface fixed and surface fixated, and even if we intermittently dip our toes beneath the sea, or regularly banquet on its bounty, it remains a place of Jaws and drowning, bristling spines and treacherous darkness.

It is this world that Angeleno and internationally acclaimed artist Doug Aitken is inviting us to reimagine. His latest artworks lie 22 miles over the sea from Los Angeles, off the Mediterranean-like shores of Catalina Island. Entering the water with a scuba tank and a square of glass an inch before our eyes, that antithetical watery world gains sudden clarity, and we perceive our earthly realm as far deeper and greater than our reckoning. “It’s really an invitation to bring people under the ocean and into a space that they might be intimidated of,” Aitken explained to me about ten minutes before I entered the water as we sat together on the shoreline of Catalina Island (me in a wetsuit that I had just managed to pull on with considerable effort), “but actually it’s living and it’s stunning. I just want to get you down there first!” He urged me, laughing and cutting our conversation short, waving me towards the water.

The bracing cold of the sea evaporates at the spectacle of an almost inconceivable number of fish. Aitken’s “Underwater Pavilions” lie a few hundred feet away—three kindred pieces at three different depths. Reaching them via the sea floor, vast ribbons of kelp and myriad life forms move in and out of the light between us—not so much like shadows, as dreams dissolving in the day. Upon reaching the sculptures where they float tethered in the midst of the water column, they are revealed as three-dimensional pentagon-sided structures that recall the futurist designs of Buckminster Fuller.

Some of the pentagonal sides are great mirrored glass lenses, while others are empty passageways offering access into the structures. Many of the surfaces—inside and out—are a rough-hewn synthetic rock—designed explicitly to capture barnacles and sea life, and therein evolve and become a part of the landscape rather than something in opposition to it. Each of the pavilions has a different flavor achieved via different combinations of materials. The deepest is externally clad in rock, and presents itself as a lone pentagon glimmering in the gloom perhaps 50 feet beneath the surface. Much of Aitkin’s past work has involved prismatic effects and vanishing perspectives, but never before has one of his projects been situated within so dynamic an environment.

“I think that the project is a living artwork.” Aitken explained to me, “A video installation is authored, someone has completed it. This work is more about opening it up, reversing that, in saying that, yes we can create this project, but in the end you’re going to see something completely different from an hour from now. Maybe a week from now there is a pod of dolphins moving around—we’ve already seen sea lions moving through. It’s just interesting that you have this crossroads where you can have a dialogue between a very feral wilderness, like a wild ocean and the viewer, or the human.”

Aitken is a superstar in the world of video and installation art. Famed for works that toy with time and space, memory and recognition, place, and perception. Aitken has been active across multiple genres since the ‘90s, and first participated in the Whitney Biennial in 1997, before taking the International Prize at the Venice Biennale in 1999. The MOCA Geffen Contemporary in Los Angeles is currently featuring Electric Earth—a comprehensive, mid-career survey exhibition that invites a striking sensory journey through the 55,000 square foot space, and of which “Underwater Pavilions,” is a companion piece.

“Underwater Pavilions” was commissioned by the organization Parley for the Oceans, and its founder Cyrill Gutsch explained their mission to me, and the circumstances that gave birth to the project: “Doug and I met at the moment where we were preparing Parley Deep Space Program which is about reinventing the idea of ocean exploration. I had a meeting at NASA JPL in Pasadena, and on the way back I visited Doug and he showed me these sketches he prepared. They felt like spaceships, they’re the symbols we need for the program. What we’re doing is connecting art, ocean, and a space community to bring back the fascination for exploration. The oceans are totally under explored,” Gutsch explained passionately, “we’re killing that life down there without even knowing it. With that program we really want to repaint and redesign the idea of environmentalism. It’s not something that should be boring or preachy. It’s something going into the future, that is building on the beauty and creativity to enhance stuff, and to come to a point where mankind and nature can live in balance.”

Aitken’s photographs and videos often extract a very human vantage point onto the natural world. Populated environments are usually desolate—car parks under snow, bus shelters, shooting ranges, motel rooms. Even high technology appears archaic somehow, and a photo of a rocket car on a desert plain seems quite as outmoded as images of plastic furniture decaying on the beach. In his photographs people tend to be indistinct and faceless, while in his videos the characters seem to occupy an indeterminacy in time and place. As Chloë Sevigny’s character explains in Aitken’s widely discussed video installation work “Black Mirror,” currently on display in Electric Earth: “Where am I from? Different places. Where did I grow up? I can’t tell you exactly. How do you get used to moving? You don’t.”

“Underwater Pavilions” is a synthesis of many of these loosely woven strands. The work will age and decay, but in doing so will evolve and grow more beautiful. People will perceive it and see it in an infinite variety of ways, yet no single encounter will hold any permanence or particular significance beyond the restricted experience of that individual. It’s both chaos and order; both narrative and time beyond meaningful cognition.

Peering out from the last of the works, and kicking away from it deeper into the light-soaked gloom, I don’t look back at the sculptures, utterly captivated instead by the fleets of silver fish swarming around me, by pumpkin-colored garibaldi, and by the vast tendrils of enchanting kelp forest ahead. Human art, even at its best, is trivially beautiful compared to the ecosystems that surround us, and it seems that reminding us of this is exactly Aitken’s intent.

Photography by Shawn Heinrichs and Patrick Fallon