F L A U N T

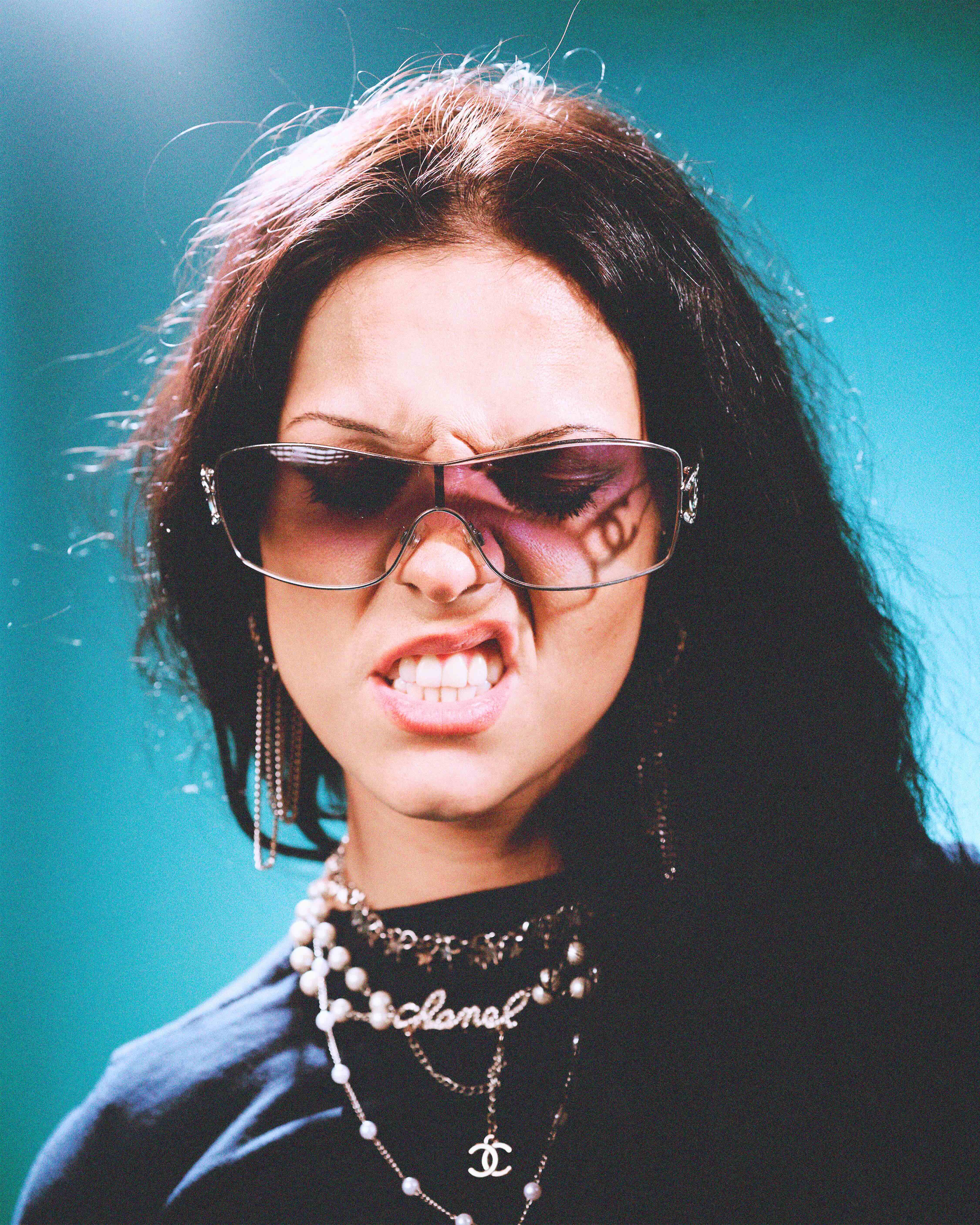

In February of this year, Reykjavík-based artist Alaska1867 released her debut album, 222. It’s a seven-track record that peruses aisles of genre but never actually settles on one identifiable sound: hi-hats and bed springs are sparsed throughout slowed, smooth rhythms, which are then met by melodic house, as if she’s ascended from the brief memory of some electro-fairy dream. In crisp, crystalline vocals, her lyrics explore desire, self-doubt, escapism, confidence, coolness, and maybe, acceptance. Here, Alaska is both hardened and vulnerable, inspired by hip-hop and pop’s evolution of the last decade, complemented with fun, sexy, carefree femininity.

Alaska1867’s real name is Kolfreyja, which, according to her, is a rarity in the country. “I think there are three in Iceland…” she continues, “A lot of people are called Freyja. She's the love goddess in Nordic mythology. But Kolfreyja is where my mom grew up, and there's a church there that my grandpa was a priest in. That's why I'm called that.” Musically and creatively inclined, she grew up in the choir and took acting classes, strongly encouraged by her family to pursue what she wanted to do. And although 222 is her debut, Alaska1867 has been releasing music since 2019, experimenting with hyperpop and drain music and uploading her songs to SoundCloud, a platform that’s long been helpful in her creative process. “I love SoundCloud because there's no pressure to make the perfect mix or the perfect album cover or the perfect song. Even though I post on Spotify, SoundCloud is so good to start for bigger projects. I can delete a song when I want to delete a song, I can switch the file when I want to switch it,” she says.

Outside of 222, there are singles that include trance-esque electronic “ChatGPT,” or “SOS” in collaboration with rapper Birnir. “SMS,” which Alaska notes is “the best song I've done,” is mystic and dreamy, suggesting some type of longing that is all-consuming, but not necessarily all-consequential.

This November, not even a year after 222’s release, Alaska1867 will perform at Iceland Airwaves, Reykjavík’s one-of-a-kind music festival. It’s long been recognized that Reykjavík harvests, within about three square miles of its downtown epicenter, an exploding ecosystem of arts, which is not only maintained by local artists but by what seems to be nearly the entirety of the community. As Alaska puts it, “I live downtown. I never want to leave downtown, because it's just this small family of people.” Iceland Airwaves is the byproduct of such community.

In addition to the local businesses that uphold the area’s artistry, there are organizations like Iceland Music, which, as the name suggests, exists to support the country’s musicians and share their music nationally and globally. We chat with Alaska1867 as she takes us around to some of the city’s major cultural arteries. Read more for places to stay and things to do in Reykjavík this November.

What was it like for you growing up in Iceland? What are your family's ideas toward creativity and music?

The culture here is so creatively driven. I was thinking about it—maybe it's because we have all this folklore, and the fantasy of elves and stuff. It kind of sounds weird, but I really do think that we've always lived off of these fantasy worlds here in Iceland.

I was also thinking about my upbringing. I grew up in Fáskrúðsfjörður, which is in the east of Iceland. I just got to run around at 4 years old in the mountains, and I’d come home at dinner time, and then I just did it again the next day. I got a lot of freedom. Also, in Iceland, we have—I don't know if I'm just lucky, but I think it's most of the people—we have really good support systems and this good ideology that women are the same as men. I grew up with my mom, who's really career-driven, and she's been a principal for 20 or 30 years, and she taught us—and her mom taught her—that it never really mattered. There's a lot of belief in you. There's a lot of trust in you to do good things, and there's a lot of belief in you to achieve good things. There was never any pressure for me to go to college or do anything. Mom and dad just said, “Just find something to do and do it.

Growing up, playing in the mountains, having that support—do you feel that impacts your creativity when you're making a song, making music?

I look at music not just as the music—you can see this through Björk, that she is the music. She has made a world around her that is just hers, and it's her imagination that has made her. Everything that she dresses in, and the way she talks, and the way she carries herself, the way she makes music, and her friends around her. Everything is her imagination spreading throughout everything. That's kind of what I strive for. I've always been really imaginative as a child, and to have this world…I've tried to make it just mine, and that's what I like about making music. It's not just about the music, it's the whole thing that I've made.

How old are you? 25 now?

I'm 25, yeah. In 2019, I started putting my music on SoundCloud, and then I just kept on doing it. Kind of didn't really think much of it. I wasn't trying to. It was just kind of an expression in a way.

Ideas about money and success are very different between American culture and Icelandic culture. Of course, artists want to make money through their art. What does that pressure look like for you? Do you work other jobs while you make music?

Of course, the dream is to make money from my job, from the thing I love to do. But there was no pressure, and I just have a job on the side. The way I see it is, if I can spend all my free time making music or making music videos, or just anything around this scene, then I'm good…I just want to live in a basement apartment downtown and have a cat. I don't want to be world famous.

[World fame] That's where things, people, can get confused.

In America, you kind of pick which life you want to do. You can live a normal life with your family, and it’s calm. Or, you can go the other way around and have this huge life, and everyone knows you, and you can't really have freedom. In Iceland, the most famous people and musicians just live here, and they go buy their groceries [as a non-famous person would].

Do you feel any difference between [being Kolfreyja] and being Alaska1867? Is there a difference there?

No, that's the kind of thing I was talking about earlier with Björk, which I like about her and about many other artists. I like the authenticity, like this is a world I've made, and it's really authentic. That's the thing I like about it the most, the character that I put on. It's just an expression. I get really confident on stage. I love being on stage. I'm meant to do this, there's no off switch. But with my family and others, I tend to get awkward and switch to being just Kolfreyja. And that's kind of a different thing. I don't really know why.

Family always knows you differently.

Yeah, they know who you are to your core.

How did you decide to name your album 222?

I have a tattoo here called 2222, like the angel number two. I believe in manifestation. I believe in God. I got sober two and a half years ago, and I started seeing this number a lot. I've kind of always had an inkling that there's something more than me, and that was my anchor to life. Seeing the number gave me reassurance that I was doing the right thing. I just called it 222, because the angel number says that's the number to the right path. It just kind of felt right. I really believe in manifestation. I make vision boards sometimes [during] the new moon. Every season, I make different vision boards, and I buy old Icelandic magazines from the 2000s from thrift shops. I clip out what I want, and I make the world I make when I’m making music. I make a vision of what kind of world I want, and everything has come true. Everything I put in my New Year's vision board has come true.

What did you learn in the making of 222? Did you play with new sounds? Was there anything that didn't work that you had to let go of?

There was this first mixtape that I released that was a finished project, and I worked on it for a year. I was always in the studio—working, working, working—and I learned how to perform because of that. I learned how to put myself out there. Before that, there was just SoundCloud, and I wasn't trying to do anything with it. So this was my first time trying to make people listen. It taught me that you just have to believe in yourself, because people aren't gonna believe in you if they haven't seen anything. I had to prove myself to myself. After 222, I started working with other producers, and they also taught me a lot of things. I always talk about this one studio session I took with BNGRBOY, one of the most famous Icelandic rappers. He put on just hi-hats, and he said, “Make lyrics.” It was scary. He was really scary. “Just make a lyric.”

And then he started telling me to pick my lyrics really carefully and look at every word and pick them really well. When I used to make lyrics before this, I wouldn’t really focus on the details. I was just trying to rhyme words and repeat words if I couldn't find any other ones. He taught me that art is art, and you have to create it carefully, with intention. So I think that taught me the most out of everything I've learned, because I hate detail. I hated doing that. I have ADHD, so I just want to start a project and then just finish it later. 222 also taught me how to finish projects, because I used to just make songs and put them on SoundCloud right away without carefully finishing them.

Maybe that version of creation is way more productive and way more valuable for the artist, as opposed to some people who don't want to put anything out unless it's perfect, and then they can never get started. You lose ideas and you lose your flow.

That's also true. I got into a rut this summer where I made a really good song called “SMS.” It's the best song I've done. After that, I was like, “Fuck, I'm never gonna make a better song.” I started overthinking every word and everything, and then I couldn't get started on anything because I was overthinking it so hard. And I was always having this expectation of myself to make it perfect. I just figured out that things don't have to be perfect, and you can make mistakes, and a song is just a song. You don't have to put it anywhere. It's kind of like a balance thing—don’t care, but also care.

Was there any kind of nervousness to share your work with your peers?

No, not really. I was always here in Reykjavík, because it's a community of people who like making art and like making music. There isn't really any pressure. When I started putting songs on SoundCloud, I didn't really care if anyone was listening. That's kind of the thing that helped to not care, because if I like it, then it’s good.

I think it's because it's so casual here...If you stand out, you're cool. If you know who you are, you're good. I think that's what helped me kind of succeed in this, because I know who I am. I'm not faking anything. That's what people call the “X Factor.” I just call it swag.

Your style, your tattoos, is that a reflection of the culture here? What does that entail?

I think it’s the mythical, underground. I think Scandinavia is really influenced by drain culture, like Yung Lean and Bladee. There’s this tattoo shop that (Street Rats Tattoo) I get most of my tattoos there. It’s these artists who are my friends, and the tattoos are also just art that they made. This is just freehand, and I just love this style. I said, “Please do art on me!” I get really influenced by, like, 2010s fashion—I'm in the space now where I love studs. There’s a vintage shop (B12 Space), I'm playing a show tonight, and they're gonna style me. I have this skirt I found, and they’re gonna style me around it. It’s all just a kind of collaboration.

This sounds like it all goes back to what you were saying earlier, about world-building, staying true to you and the people around you.

Most of the people at these places, most of them grew up here in Prikið. That's where it all started. This is the home of culture. It’s funny because it's such a small place. This house is protected by the government, so it hasn't been changed since 1951. It's the oldest coffee shop in Iceland–these are the same tables, and this is the same floor, and the same bar [as when it first opened].

As Alaska mentioned, Prikið is one of Reykjavík’s oldest coffee shops, serving as a cafe by day and a bar and venue space by night. Prikið is also the mother to Sticky Records, which was born in 2016 and exists “to support local artists, the known and the unknown, to finalize projects and see them through with support of live events and physical renditions of work.” This is exactly what Sticky Records did for Alaska and 222. According to her, Geoff, Prikið’s owner, “believed in me so much, you could see that he wanted to encourage me. He put money into [222] and he didn't really want anything in exchange. I just play here when he asks. He helped me, he helped us, me and Whyrun, who produced the album, he helped us put it through the mix, and he helped us pay for the album cover. He paid for everything. It's just unheard of. I'm not signed to him. He distributed the album, but he doesn't own any of the masters or anything. This trust he has—and you trust him—he's done that with a lot of people.” Sticky Records is Iceland’s only pro-bono record label.

Street Rats Tattoo opened in 2020. Surviving the pandemic, this tattoo and piercing shop is heavily influenced by the history of tattoos and tattooing culture. For example, there’s a flash sheet of popular tattoo trends in the 90s, reimagined to be more Iceland-specific. Co-founded by Iceland’s Kristófer, the tattoo artists who work here are both national and international, each practicing their own unique style. Apparently, the store is registered officially as an art museum rather than a tattoo shop, considering all the tattoo art hanging on the walls are original, hand-drawn works. This is a place where tourists swing by for their souvenir tattoos, and it’s also where Alaska gets most of her body art done.

“The first and only arthouse cinema in Iceland” is not more than a few steps down the street from Street Rats, a perfectly designed classic arthouse cinema in Reykjavík. Enter and submit your ticket, grab concessions at the vibrant, neon snack stand, and enjoy the eclectic lounge area, outside of the theatres. Bíó Paradís shows older classics alongside newer projects, and will host a Nordic Film Festival this week, September 18 to 22. Bíó Paradís is a part of Heimilis kivminanna ses, a non-profit that is made up of several different filmmaker associations within Iceland.

Smekkleysa (Bad Taste Records) has been a record store and label for 35 years and operates as a coffee house, venue, exhibition space, and really, is another core creative gathering spot for Reykjavík's artists. This space has deep history in the music, arts, and literature circles of the city, with a focus always on the underground, grassroots scenes. Each Saturday, Drif, a community of experimental DJs, plays from 2-6. Sometimes, when there’s a full moon, Björk performs a set (no pictures allowed). Read excerpts from their manifesto, World Domination or Death, on their website.

Operating since 2023, B12 Space is a highly curated vintage shop run by sisters Fríd (also a musician) and Theodora. What started as a sewing studio in collaboration with fellow designers from Fríd’s Icelandic Academy of Arts has turned into a mecca for unique pieces sourced from all over Europe, in which Fríd and Theodora only choose pieces they truly love, rather than pulling something for it’s brand name alone. They’re ever-inspired by their own customers, who note a certain bravery, a courage in Icelandic youth, to wear what they want rather than wear what might be considered normal. On the day we speak with Alaska, B12 is styling her for her Oktoberfest performance. They collectively decide to throw out one of Alaska’s pleated skirts, green with pink flowers, for a fitted, vintage red leather jacket that stops at the hip, paired with low-rise reconstructed denim.

While Reykjavík is physically small, the variety of activities and attractions against the natural beauty of the country is unceasing. For those traveling, the city itself is roughly a 45-minute Icelandia & Flybus trip to and from Keflavík International Airport. In the city itself, Center Hotels has nine locations throughout Reykjavík, each with its own unique approach to comfort and within walking distance of the venues that are part of Iceland Airwaves. Here, breakfast is included, while locations also offers restaurants, bars/lounges, and coffee shops.

For post-festival recovery, we recommend relaxing at Sky Lagoon, a geothermal spa and an ode to Iceland’s bath culture that looks over the sea. It has a massive sauna with glass windows positioned right above the water, a soothing body scrub to lather in before entering the steam room, and state-of-the-art hot and cold atmospheres set against impressive interior design. And finally, to get in and out of the country, Iceland Air offers international flights, and even ticket packaging with Iceland Airwaves. Tickets for Iceland Airwaves 2025 are on sale now, including flight and ticket packages provided by Iceland Air.