Illustrations by Michelle Garcia.

The Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet, a retirement convent in the hills of Brentwood, is not unlike a sorority, that is, if all the pledges were senile Catholic nuns in post-Vatican-II leisurewear. The women eat together, gossip about one another, participate in communal recreation, and sneak nips into the dining hall to spike their soda waters. Some of the Sisters have been in the same cohort for over eighty years. Though they have their daily liturgy, the Carondelet nuns are far more committed to each other than to their collective husband.

Over two-hundred nuns occupy the Carondelet, a truly breathtaking piece of LA real estate. On its twelves acres, there are several chapels, a meditation garden, multiple dining halls, a bingo lounge, and—as a signifier that might only orient Angelenos—views comparable to those at the Getty. That goes to say, the view is not too shabby. Bar recent wildfires, one couldn’t find a more peaceful place to grow old. Yet there is something paradigmatic about the Carondelet and its occupants: it’s a multi-million dollar mansion in one of the most expensive neighborhoods in the world housing hundreds of women who have taken a vow of poverty. Their belief system is completely antithetical to their late-in-lifestyle which totes private chefs and $5,000 ellipticals. But these luxuries, mere perks, are not what being a Sister is all about.

Many of the nuns joined St. Joseph’s in the Roaring Twenties, the convent being one of only a few viable options for women at the time. You could be a secretary, raise a family or become a nun, “and the convent seemed a lot more interesting,” Sister Piatra, a nun with a thick Long Island accent who smells like the peppermints she keeps tucked in her robes, tells me. She has been with the congregation since 1924. (1) Through the order, Sister Piatra was able to receive an education, travel the world, teach, and meet the Pope. “I wasn’t even a Catholic,” she laughs.

For a community predicated on charity, chastity, and obedience, the Sisters got into an awful lot of mischief. Sister Piatra rehashed some of their teenage years, sneaking cigarettes up to the roof of wherever they were stationed, and playing Gin Rummy. “It was the most freedom you could have as a woman,” she recalls, wistfully.

“But no men?” I clarify.

“No men. (2) That’s why we live so long.”

There might be some truth to this. Sister Piatra is 101 years old, and she’s on the younger side of the age median.

Because of the community’s mature age, some of the most integral members behind the convent walls aren’t women of the cloth at all, but rather their caretakers like Susan Kemper (she requests her real name be omitted for legal reasons), a hospice nurse for the parent company, Vitas. Kemper has been working with the nuns for over three years and has grown fond of them and their antics. Though many now have Alzheimer’s, they still regale Kemper with—albeit jumbled—anecdotes from their lives in the convent. Some of the nuns, having trained as nurses themselves, provided aid during the Korean war and tended Malaria and Ebola patients in Africa.

But the adventure is over, Kemper tells me somberly. Once the nuns are sent to the Carondelet, they rarely leave again. Its campus is all that the Sisters will ever see of Los Angeles. “Essentially, they can’t go out on their own and there is no one to take them anywhere. They never made families. The order is all they know.”

The upkeep of their home is paid for by donations, and the property itself was a donation by the city of Bel Air in the 1940s, thanking the nuns for their lives of piety and service. Now they are something of prisoners in their mountainous palace, occupied by prayer and pilates for the rest of their time on earth. The nuns appreciate their home, but such active women must get agitated by placidity. Sister Ann Foster, a chipper, petite woman with hands gnarled from arthritis, says she wanted to retire in LA so that she could see the ocean. In over a decade living at the Carondelet, she never left the premises.

When I meet Sister Ann Foster, she is looking forward to her upcoming birthday; the big one-oh-six. She is, Kemper confesses, one of her favorite patients. The staff celebrates birthdays often, and always in the same way: a cheesecake with cherries is cut in honor of the aging nun and distributed at the dining hall. Many of the Sisters express, colorfully, that the tradition is tired. Quite simply, they’re sick of cheesecake. “Fuck cheesecake,” Sister Josephine, a four-foot-nine raspy-voiced Irish woman, says in her thick brogue. A few others chime in in agreement, “Yeah, fuck it!”

“SAF (Sister Anne Foster) asked me for a favor for her 106th,” Kemper discloses to me. “She wanted to go to the beach.”

At the time, SAF was on hospice, which meant her doctor anticipated her passing within the year. But during my visits, while I watch her stroll around the property with her best friend, Sister Mary Ellen (age 104), on their respective walkers, I have to admit that she appeared healthy and alert. (3)

Kemper, touched by SAF’s birthday wish, asked her company if she could take the Sister to the beach over the weekend. To Kemper’s dismay, her request was vehemently denied, solidifying the nun’s life sentence to her retirement home. Vitas could not be responsible for a patient outside of the Carondelet. Taking SAF more than a foot from the driveway was strictly prohibited and could result in Kemper losing her RN license.

At the Vitas corporate office in Encino, I speak with Chris Allen, who denied Kemper’s request. I point out that he has the same name as the 8th winner of American Idol, to which he has no comment. It’s all very by-the-book over there. “We love Susan,” says Chris. “She is a wonderful, compassionate nurse and one of our best charters. Her line of work is morbid and it’s a nice thing she wants to do.” But he couldn’t let her take a dying nun with dementia and an oxygen tank to Malibu. “She could lose her job and we could all get sued.”

“It’s cruel,” Kemper responds. “On a clear day, the nuns can see the ocean from the patio.” She explains that Sister Anne Foster’s oxygen tank is precautionary. “And they’re portable.” It is apparent that she had already hatched a plan.

The hospice nurses’ aid, Janet Walsh (for her privacy, her name has also been changed), is brassy, outspoken, and surprisingly lighthearted for a woman in such a bleak line of work. She is the perfect comic relief in a crime story, and laugh when I tell her so. Walsh, too, has developed an affinity for the nuns and knows them all intimately. “I mean, I’ve been wiping their asses for five years if that’s what you mean,” she says. Walsh especially likes Sister Anne Foster. “It’s like she has Tourettes sometimes,” Walsh laughs, “but we have fun. And that broad can shoot pool.”

After Vitas’ veto, Kemper and Walsh broach the subject with the Mother Superior, head honcho at the Carondelet. She’s a stern Venezuelan woman of few words—no words, in fact, as she declined an interview with me. Kemper and Walsh explain that they intend, on the morning of her 106th birthday, to take Sister Anna Foster and Sister Mary Ellen to Will Rogers, a beach where you can rent wheelchairs with industrial tires that truck through sand. Kemper delineates the medical precautions that she’ll be taking and promises they’ll be back in time for cheese-cake. Kemper describes the conversation to me, how the Mother Superior turned her head towards a crucifix mounted on the wall, a limp half-naked Jesus dangling from it. “I’m looking the other way,” she said.

\*\*\*

Walsh and Kemper take turns enigmatically telling me their story. At dawn, the nurses pile gauze, diapers, IVs, and a thermos of frozen margaritas into Kemper’s Ford Fusion. They drive up the winding hill and idle outside like nervous bank robbers. When they wake SAF, she’s startled, not recognizing them without their scrubs. “Are you here to kill me?” she asks. Kemper reminds the nun that they were there to take her to the beach.

The nuns are giddy as the car pulls out of the driveway, in their case, for the first time in ten years. Both Sisters recently joined Facebook, and Walsh has to actively prevent them from posting pictures of the PCH. (4) The sun is coming up as they get the nuns in their sand wheelchairs and walk onto the bluff. There are tears in Sister Anne Foster’s eyes as she looks out at the horizon.

They stop for breakfast locally. Sister Mary Ellen reveals to the staff that she has never tried guacamole, and three orders are sent to their table on the house, and the whole restaurant sings “Happy Birthday.” SAF is so overwhelmed, grateful, and drunk, that she leans back and fell asleep.

The Sisters are giggling like school girls when they return to the Carondelet, and Kemper knew it wouldn’t be long before the whole congregation heard about their tryst off-campus. “I told them not to brag to the other nuns,” she recollects. “They can get kind of boastful and then we’d have two-hundred Sisters asking us to take them somewhere.”

That afternoon, the nurses are summoned by the Mother Superior to meet in the chapel. They are nervous, bracing themselves for a lecture, wondering the extent of the trouble they are in. “She could have had us arrested,” Foster tells me. Walsh adds, “I’m not a religious woman, but at that moment, I was praying my ass off.” When they enter, the Mother Superior stares at them for a long time. She touches them behind each shoulder, her rigidness melting. “You see that, there and there?” she says. “You have wings.”

For weeks after the heist, Kemper says that she jumped every time her phone rang. She was afraid that corporate had received word of Nungate and was calling to fire her, or perhaps send her to jail for elder-napping. But nothing happened. Work continued as usual. Like they predicted, Anne Foster couldn’t help but tell all of the Sisters about her adventure, and Kemper and Walsh were inundated with requests to sneak nuns out to the Hollywood Sign, to Disneyland—one Sister even wanted a double-double from In-N-Out.

\*\*\*

Almost a year has passed since the beach trip. Sister Anne Foster is nearing 107 and still in relatively good health. Remarkably, she has been taken off hospice. Sister Mary Ellen passed away last April, and SAF mourns her deeply.

Sisters like Mary Ellen are literally a dying breed. Her generation of nuns may be the last of St. Joseph’s congregation. “Young women aren’t joining the convent anymore,” Foster notes. The parish isn’t as appealing for women in this day and age. Priests are permitted to get married and make a salary while nuns have almost as few rights as they did in the 1920s. (5) What was once a path to freedom is now regressive and antiquated. When SAG mourns Mary Ellen, she’s also mourning their heyday, a time when nuns were lauded for their service: Catholic celebrities in their habits. Now, she feels like a relic in a museum.

“There isn’t a place in our world for them,” Walsh tells me as we walk through the rec room. One nun screams “Checkmate!” at another, and we notice that neither of them are playing chess. However, the Carondelet doesn’t feel like a museum to me. It’s a community unlike any I’ve ever seen; a Sisterhood in the truest sense. They are a coalition of women trying to help each other and humanity, and such a coalition can exist without the looming enmity of God. Walsh says she’d kill to have spent her adolescence in the convent. It’s like an altruistic boarding school from which you never graduate. I understand why these nurses risked their careers to take two nuns to the beach. Foster and Walsh are unofficial members of this club, unholy adjuncts, and that’s what you do for your fellow Sisters.

* * *

1\. Sister Piatra occupied the East Coast campus. The Carondelet wasn’t even purchased until the 1940s. Before then, the land was still orange groves.

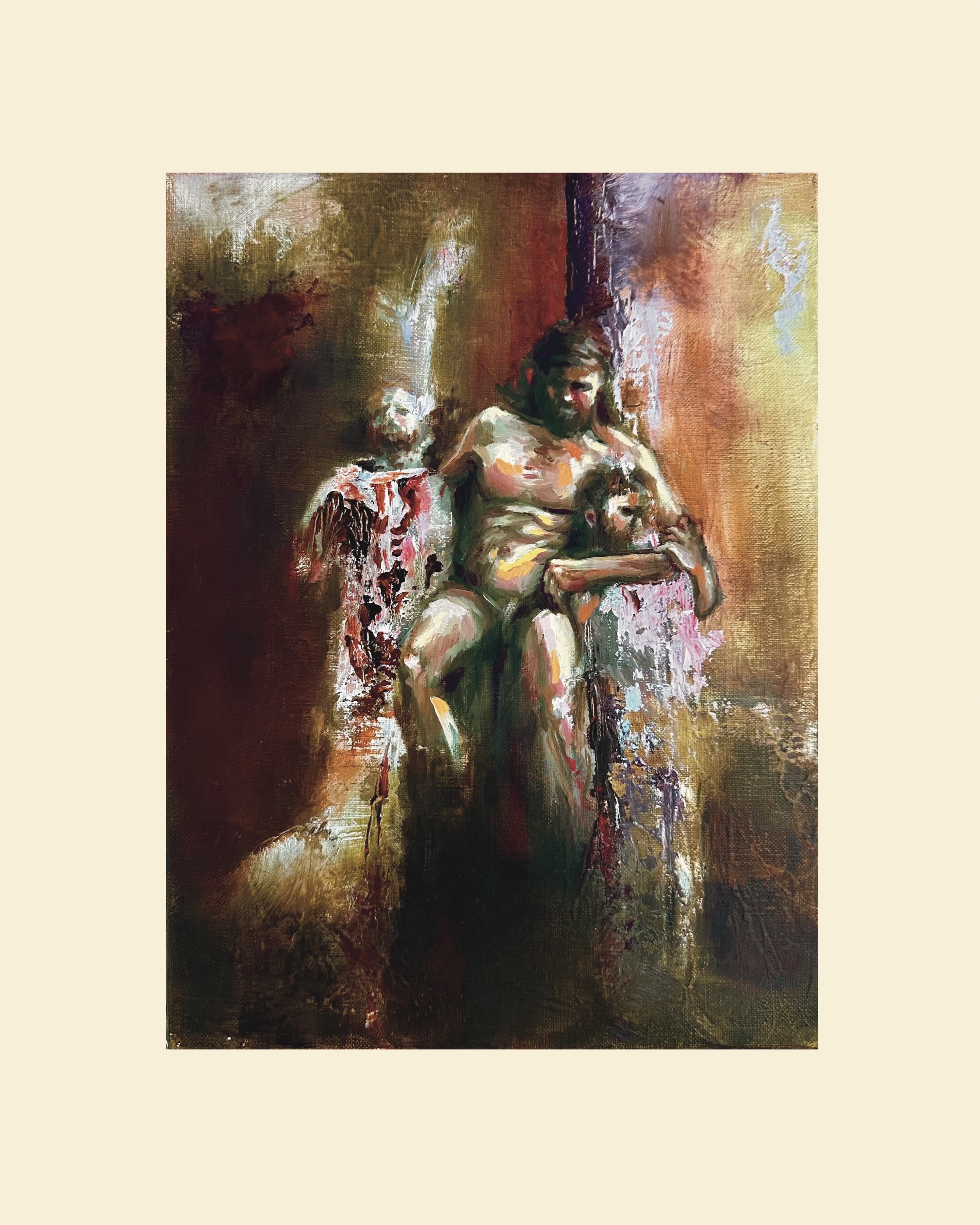

2\. Sister Piatra says she’s never seen a naked man, but in some of the portraiture of the crucifiction, Jesus’ scant robes are quite revealing.

3\. In their down time, they have been playing pool on the donated billiards table. Kemper is sure, despite their arthritis, that the two could go pro.

4\. The Sisters are all infatuated with Facebook. When a bevy of laptops were donated to the Carondelet, the nuns had a field day setting up profiles and taking pictures in their habits. Many are still engaged in some hostile “poke wars” with one another. “Ann Margret \[from the East Coast branch\] wasn’t accepting my friend request,” says Sister Josephine, “and I was pissed at her for about a week until I heard she had died!”

5\. They can wear pants now.

Illustrations by Michelle Garcia.

The Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet, a retirement convent in the hills of Brentwood, is not unlike a sorority, that is, if all the pledges were senile Catholic nuns in post-Vatican-II leisurewear. The women eat together, gossip about one another, participate in communal recreation, and sneak nips into the dining hall to spike their soda waters. Some of the Sisters have been in the same cohort for over eighty years. Though they have their daily liturgy, the Carondelet nuns are far more committed to each other than to their collective husband.

Over two-hundred nuns occupy the Carondelet, a truly breathtaking piece of LA real estate. On its twelves acres, there are several chapels, a meditation garden, multiple dining halls, a bingo lounge, and—as a signifier that might only orient Angelenos—views comparable to those at the Getty. That goes to say, the view is not too shabby. Bar recent wildfires, one couldn’t find a more peaceful place to grow old. Yet there is something paradigmatic about the Carondelet and its occupants: it’s a multi-million dollar mansion in one of the most expensive neighborhoods in the world housing hundreds of women who have taken a vow of poverty. Their belief system is completely antithetical to their late-in-lifestyle which totes private chefs and $5,000 ellipticals. But these luxuries, mere perks, are not what being a Sister is all about.

Many of the nuns joined St. Joseph’s in the Roaring Twenties, the convent being one of only a few viable options for women at the time. You could be a secretary, raise a family or become a nun, “and the convent seemed a lot more interesting,” Sister Piatra, a nun with a thick Long Island accent who smells like the peppermints she keeps tucked in her robes, tells me. She has been with the congregation since 1924. (1) Through the order, Sister Piatra was able to receive an education, travel the world, teach, and meet the Pope. “I wasn’t even a Catholic,” she laughs.

For a community predicated on charity, chastity, and obedience, the Sisters got into an awful lot of mischief. Sister Piatra rehashed some of their teenage years, sneaking cigarettes up to the roof of wherever they were stationed, and playing Gin Rummy. “It was the most freedom you could have as a woman,” she recalls, wistfully.

“But no men?” I clarify.

“No men. (2) That’s why we live so long.”

There might be some truth to this. Sister Piatra is 101 years old, and she’s on the younger side of the age median.

Because of the community’s mature age, some of the most integral members behind the convent walls aren’t women of the cloth at all, but rather their caretakers like Susan Kemper (she requests her real name be omitted for legal reasons), a hospice nurse for the parent company, Vitas. Kemper has been working with the nuns for over three years and has grown fond of them and their antics. Though many now have Alzheimer’s, they still regale Kemper with—albeit jumbled—anecdotes from their lives in the convent. Some of the nuns, having trained as nurses themselves, provided aid during the Korean war and tended Malaria and Ebola patients in Africa.

But the adventure is over, Kemper tells me somberly. Once the nuns are sent to the Carondelet, they rarely leave again. Its campus is all that the Sisters will ever see of Los Angeles. “Essentially, they can’t go out on their own and there is no one to take them anywhere. They never made families. The order is all they know.”

The upkeep of their home is paid for by donations, and the property itself was a donation by the city of Bel Air in the 1940s, thanking the nuns for their lives of piety and service. Now they are something of prisoners in their mountainous palace, occupied by prayer and pilates for the rest of their time on earth. The nuns appreciate their home, but such active women must get agitated by placidity. Sister Ann Foster, a chipper, petite woman with hands gnarled from arthritis, says she wanted to retire in LA so that she could see the ocean. In over a decade living at the Carondelet, she never left the premises.

When I meet Sister Ann Foster, she is looking forward to her upcoming birthday; the big one-oh-six. She is, Kemper confesses, one of her favorite patients. The staff celebrates birthdays often, and always in the same way: a cheesecake with cherries is cut in honor of the aging nun and distributed at the dining hall. Many of the Sisters express, colorfully, that the tradition is tired. Quite simply, they’re sick of cheesecake. “Fuck cheesecake,” Sister Josephine, a four-foot-nine raspy-voiced Irish woman, says in her thick brogue. A few others chime in in agreement, “Yeah, fuck it!”

“SAF (Sister Anne Foster) asked me for a favor for her 106th,” Kemper discloses to me. “She wanted to go to the beach.”

At the time, SAF was on hospice, which meant her doctor anticipated her passing within the year. But during my visits, while I watch her stroll around the property with her best friend, Sister Mary Ellen (age 104), on their respective walkers, I have to admit that she appeared healthy and alert. (3)

Kemper, touched by SAF’s birthday wish, asked her company if she could take the Sister to the beach over the weekend. To Kemper’s dismay, her request was vehemently denied, solidifying the nun’s life sentence to her retirement home. Vitas could not be responsible for a patient outside of the Carondelet. Taking SAF more than a foot from the driveway was strictly prohibited and could result in Kemper losing her RN license.

At the Vitas corporate office in Encino, I speak with Chris Allen, who denied Kemper’s request. I point out that he has the same name as the 8th winner of American Idol, to which he has no comment. It’s all very by-the-book over there. “We love Susan,” says Chris. “She is a wonderful, compassionate nurse and one of our best charters. Her line of work is morbid and it’s a nice thing she wants to do.” But he couldn’t let her take a dying nun with dementia and an oxygen tank to Malibu. “She could lose her job and we could all get sued.”

“It’s cruel,” Kemper responds. “On a clear day, the nuns can see the ocean from the patio.” She explains that Sister Anne Foster’s oxygen tank is precautionary. “And they’re portable.” It is apparent that she had already hatched a plan.

The hospice nurses’ aid, Janet Walsh (for her privacy, her name has also been changed), is brassy, outspoken, and surprisingly lighthearted for a woman in such a bleak line of work. She is the perfect comic relief in a crime story, and laugh when I tell her so. Walsh, too, has developed an affinity for the nuns and knows them all intimately. “I mean, I’ve been wiping their asses for five years if that’s what you mean,” she says. Walsh especially likes Sister Anne Foster. “It’s like she has Tourettes sometimes,” Walsh laughs, “but we have fun. And that broad can shoot pool.”

After Vitas’ veto, Kemper and Walsh broach the subject with the Mother Superior, head honcho at the Carondelet. She’s a stern Venezuelan woman of few words—no words, in fact, as she declined an interview with me. Kemper and Walsh explain that they intend, on the morning of her 106th birthday, to take Sister Anna Foster and Sister Mary Ellen to Will Rogers, a beach where you can rent wheelchairs with industrial tires that truck through sand. Kemper delineates the medical precautions that she’ll be taking and promises they’ll be back in time for cheese-cake. Kemper describes the conversation to me, how the Mother Superior turned her head towards a crucifix mounted on the wall, a limp half-naked Jesus dangling from it. “I’m looking the other way,” she said.

\*\*\*

Walsh and Kemper take turns enigmatically telling me their story. At dawn, the nurses pile gauze, diapers, IVs, and a thermos of frozen margaritas into Kemper’s Ford Fusion. They drive up the winding hill and idle outside like nervous bank robbers. When they wake SAF, she’s startled, not recognizing them without their scrubs. “Are you here to kill me?” she asks. Kemper reminds the nun that they were there to take her to the beach.

The nuns are giddy as the car pulls out of the driveway, in their case, for the first time in ten years. Both Sisters recently joined Facebook, and Walsh has to actively prevent them from posting pictures of the PCH. (4) The sun is coming up as they get the nuns in their sand wheelchairs and walk onto the bluff. There are tears in Sister Anne Foster’s eyes as she looks out at the horizon.

They stop for breakfast locally. Sister Mary Ellen reveals to the staff that she has never tried guacamole, and three orders are sent to their table on the house, and the whole restaurant sings “Happy Birthday.” SAF is so overwhelmed, grateful, and drunk, that she leans back and fell asleep.

The Sisters are giggling like school girls when they return to the Carondelet, and Kemper knew it wouldn’t be long before the whole congregation heard about their tryst off-campus. “I told them not to brag to the other nuns,” she recollects. “They can get kind of boastful and then we’d have two-hundred Sisters asking us to take them somewhere.”

That afternoon, the nurses are summoned by the Mother Superior to meet in the chapel. They are nervous, bracing themselves for a lecture, wondering the extent of the trouble they are in. “She could have had us arrested,” Foster tells me. Walsh adds, “I’m not a religious woman, but at that moment, I was praying my ass off.” When they enter, the Mother Superior stares at them for a long time. She touches them behind each shoulder, her rigidness melting. “You see that, there and there?” she says. “You have wings.”

For weeks after the heist, Kemper says that she jumped every time her phone rang. She was afraid that corporate had received word of Nungate and was calling to fire her, or perhaps send her to jail for elder-napping. But nothing happened. Work continued as usual. Like they predicted, Anne Foster couldn’t help but tell all of the Sisters about her adventure, and Kemper and Walsh were inundated with requests to sneak nuns out to the Hollywood Sign, to Disneyland—one Sister even wanted a double-double from In-N-Out.

\*\*\*

Almost a year has passed since the beach trip. Sister Anne Foster is nearing 107 and still in relatively good health. Remarkably, she has been taken off hospice. Sister Mary Ellen passed away last April, and SAF mourns her deeply.

Sisters like Mary Ellen are literally a dying breed. Her generation of nuns may be the last of St. Joseph’s congregation. “Young women aren’t joining the convent anymore,” Foster notes. The parish isn’t as appealing for women in this day and age. Priests are permitted to get married and make a salary while nuns have almost as few rights as they did in the 1920s. (5) What was once a path to freedom is now regressive and antiquated. When SAG mourns Mary Ellen, she’s also mourning their heyday, a time when nuns were lauded for their service: Catholic celebrities in their habits. Now, she feels like a relic in a museum.

“There isn’t a place in our world for them,” Walsh tells me as we walk through the rec room. One nun screams “Checkmate!” at another, and we notice that neither of them are playing chess. However, the Carondelet doesn’t feel like a museum to me. It’s a community unlike any I’ve ever seen; a Sisterhood in the truest sense. They are a coalition of women trying to help each other and humanity, and such a coalition can exist without the looming enmity of God. Walsh says she’d kill to have spent her adolescence in the convent. It’s like an altruistic boarding school from which you never graduate. I understand why these nurses risked their careers to take two nuns to the beach. Foster and Walsh are unofficial members of this club, unholy adjuncts, and that’s what you do for your fellow Sisters.

* * *

1\. Sister Piatra occupied the East Coast campus. The Carondelet wasn’t even purchased until the 1940s. Before then, the land was still orange groves.

2\. Sister Piatra says she’s never seen a naked man, but in some of the portraiture of the crucifiction, Jesus’ scant robes are quite revealing.

3\. In their down time, they have been playing pool on the donated billiards table. Kemper is sure, despite their arthritis, that the two could go pro.

4\. The Sisters are all infatuated with Facebook. When a bevy of laptops were donated to the Carondelet, the nuns had a field day setting up profiles and taking pictures in their habits. Many are still engaged in some hostile “poke wars” with one another. “Ann Margret \[from the East Coast branch\] wasn’t accepting my friend request,” says Sister Josephine, “and I was pissed at her for about a week until I heard she had died!”

5\. They can wear pants now.

Illustrations by Michelle Garcia.

The Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet, a retirement convent in the hills of Brentwood, is not unlike a sorority, that is, if all the pledges were senile Catholic nuns in post-Vatican-II leisurewear. The women eat together, gossip about one another, participate in communal recreation, and sneak nips into the dining hall to spike their soda waters. Some of the Sisters have been in the same cohort for over eighty years. Though they have their daily liturgy, the Carondelet nuns are far more committed to each other than to their collective husband.

Over two-hundred nuns occupy the Carondelet, a truly breathtaking piece of LA real estate. On its twelves acres, there are several chapels, a meditation garden, multiple dining halls, a bingo lounge, and—as a signifier that might only orient Angelenos—views comparable to those at the Getty. That goes to say, the view is not too shabby. Bar recent wildfires, one couldn’t find a more peaceful place to grow old. Yet there is something paradigmatic about the Carondelet and its occupants: it’s a multi-million dollar mansion in one of the most expensive neighborhoods in the world housing hundreds of women who have taken a vow of poverty. Their belief system is completely antithetical to their late-in-lifestyle which totes private chefs and $5,000 ellipticals. But these luxuries, mere perks, are not what being a Sister is all about.

Many of the nuns joined St. Joseph’s in the Roaring Twenties, the convent being one of only a few viable options for women at the time. You could be a secretary, raise a family or become a nun, “and the convent seemed a lot more interesting,” Sister Piatra, a nun with a thick Long Island accent who smells like the peppermints she keeps tucked in her robes, tells me. She has been with the congregation since 1924. (1) Through the order, Sister Piatra was able to receive an education, travel the world, teach, and meet the Pope. “I wasn’t even a Catholic,” she laughs.

For a community predicated on charity, chastity, and obedience, the Sisters got into an awful lot of mischief. Sister Piatra rehashed some of their teenage years, sneaking cigarettes up to the roof of wherever they were stationed, and playing Gin Rummy. “It was the most freedom you could have as a woman,” she recalls, wistfully.

“But no men?” I clarify.

“No men. (2) That’s why we live so long.”

There might be some truth to this. Sister Piatra is 101 years old, and she’s on the younger side of the age median.

Because of the community’s mature age, some of the most integral members behind the convent walls aren’t women of the cloth at all, but rather their caretakers like Susan Kemper (she requests her real name be omitted for legal reasons), a hospice nurse for the parent company, Vitas. Kemper has been working with the nuns for over three years and has grown fond of them and their antics. Though many now have Alzheimer’s, they still regale Kemper with—albeit jumbled—anecdotes from their lives in the convent. Some of the nuns, having trained as nurses themselves, provided aid during the Korean war and tended Malaria and Ebola patients in Africa.

But the adventure is over, Kemper tells me somberly. Once the nuns are sent to the Carondelet, they rarely leave again. Its campus is all that the Sisters will ever see of Los Angeles. “Essentially, they can’t go out on their own and there is no one to take them anywhere. They never made families. The order is all they know.”

The upkeep of their home is paid for by donations, and the property itself was a donation by the city of Bel Air in the 1940s, thanking the nuns for their lives of piety and service. Now they are something of prisoners in their mountainous palace, occupied by prayer and pilates for the rest of their time on earth. The nuns appreciate their home, but such active women must get agitated by placidity. Sister Ann Foster, a chipper, petite woman with hands gnarled from arthritis, says she wanted to retire in LA so that she could see the ocean. In over a decade living at the Carondelet, she never left the premises.

When I meet Sister Ann Foster, she is looking forward to her upcoming birthday; the big one-oh-six. She is, Kemper confesses, one of her favorite patients. The staff celebrates birthdays often, and always in the same way: a cheesecake with cherries is cut in honor of the aging nun and distributed at the dining hall. Many of the Sisters express, colorfully, that the tradition is tired. Quite simply, they’re sick of cheesecake. “Fuck cheesecake,” Sister Josephine, a four-foot-nine raspy-voiced Irish woman, says in her thick brogue. A few others chime in in agreement, “Yeah, fuck it!”

“SAF (Sister Anne Foster) asked me for a favor for her 106th,” Kemper discloses to me. “She wanted to go to the beach.”

At the time, SAF was on hospice, which meant her doctor anticipated her passing within the year. But during my visits, while I watch her stroll around the property with her best friend, Sister Mary Ellen (age 104), on their respective walkers, I have to admit that she appeared healthy and alert. (3)

Kemper, touched by SAF’s birthday wish, asked her company if she could take the Sister to the beach over the weekend. To Kemper’s dismay, her request was vehemently denied, solidifying the nun’s life sentence to her retirement home. Vitas could not be responsible for a patient outside of the Carondelet. Taking SAF more than a foot from the driveway was strictly prohibited and could result in Kemper losing her RN license.

At the Vitas corporate office in Encino, I speak with Chris Allen, who denied Kemper’s request. I point out that he has the same name as the 8th winner of American Idol, to which he has no comment. It’s all very by-the-book over there. “We love Susan,” says Chris. “She is a wonderful, compassionate nurse and one of our best charters. Her line of work is morbid and it’s a nice thing she wants to do.” But he couldn’t let her take a dying nun with dementia and an oxygen tank to Malibu. “She could lose her job and we could all get sued.”

“It’s cruel,” Kemper responds. “On a clear day, the nuns can see the ocean from the patio.” She explains that Sister Anne Foster’s oxygen tank is precautionary. “And they’re portable.” It is apparent that she had already hatched a plan.

The hospice nurses’ aid, Janet Walsh (for her privacy, her name has also been changed), is brassy, outspoken, and surprisingly lighthearted for a woman in such a bleak line of work. She is the perfect comic relief in a crime story, and laugh when I tell her so. Walsh, too, has developed an affinity for the nuns and knows them all intimately. “I mean, I’ve been wiping their asses for five years if that’s what you mean,” she says. Walsh especially likes Sister Anne Foster. “It’s like she has Tourettes sometimes,” Walsh laughs, “but we have fun. And that broad can shoot pool.”

After Vitas’ veto, Kemper and Walsh broach the subject with the Mother Superior, head honcho at the Carondelet. She’s a stern Venezuelan woman of few words—no words, in fact, as she declined an interview with me. Kemper and Walsh explain that they intend, on the morning of her 106th birthday, to take Sister Anna Foster and Sister Mary Ellen to Will Rogers, a beach where you can rent wheelchairs with industrial tires that truck through sand. Kemper delineates the medical precautions that she’ll be taking and promises they’ll be back in time for cheese-cake. Kemper describes the conversation to me, how the Mother Superior turned her head towards a crucifix mounted on the wall, a limp half-naked Jesus dangling from it. “I’m looking the other way,” she said.

\*\*\*

Walsh and Kemper take turns enigmatically telling me their story. At dawn, the nurses pile gauze, diapers, IVs, and a thermos of frozen margaritas into Kemper’s Ford Fusion. They drive up the winding hill and idle outside like nervous bank robbers. When they wake SAF, she’s startled, not recognizing them without their scrubs. “Are you here to kill me?” she asks. Kemper reminds the nun that they were there to take her to the beach.

The nuns are giddy as the car pulls out of the driveway, in their case, for the first time in ten years. Both Sisters recently joined Facebook, and Walsh has to actively prevent them from posting pictures of the PCH. (4) The sun is coming up as they get the nuns in their sand wheelchairs and walk onto the bluff. There are tears in Sister Anne Foster’s eyes as she looks out at the horizon.

They stop for breakfast locally. Sister Mary Ellen reveals to the staff that she has never tried guacamole, and three orders are sent to their table on the house, and the whole restaurant sings “Happy Birthday.” SAF is so overwhelmed, grateful, and drunk, that she leans back and fell asleep.

The Sisters are giggling like school girls when they return to the Carondelet, and Kemper knew it wouldn’t be long before the whole congregation heard about their tryst off-campus. “I told them not to brag to the other nuns,” she recollects. “They can get kind of boastful and then we’d have two-hundred Sisters asking us to take them somewhere.”

That afternoon, the nurses are summoned by the Mother Superior to meet in the chapel. They are nervous, bracing themselves for a lecture, wondering the extent of the trouble they are in. “She could have had us arrested,” Foster tells me. Walsh adds, “I’m not a religious woman, but at that moment, I was praying my ass off.” When they enter, the Mother Superior stares at them for a long time. She touches them behind each shoulder, her rigidness melting. “You see that, there and there?” she says. “You have wings.”

For weeks after the heist, Kemper says that she jumped every time her phone rang. She was afraid that corporate had received word of Nungate and was calling to fire her, or perhaps send her to jail for elder-napping. But nothing happened. Work continued as usual. Like they predicted, Anne Foster couldn’t help but tell all of the Sisters about her adventure, and Kemper and Walsh were inundated with requests to sneak nuns out to the Hollywood Sign, to Disneyland—one Sister even wanted a double-double from In-N-Out.

\*\*\*

Almost a year has passed since the beach trip. Sister Anne Foster is nearing 107 and still in relatively good health. Remarkably, she has been taken off hospice. Sister Mary Ellen passed away last April, and SAF mourns her deeply.

Sisters like Mary Ellen are literally a dying breed. Her generation of nuns may be the last of St. Joseph’s congregation. “Young women aren’t joining the convent anymore,” Foster notes. The parish isn’t as appealing for women in this day and age. Priests are permitted to get married and make a salary while nuns have almost as few rights as they did in the 1920s. (5) What was once a path to freedom is now regressive and antiquated. When SAG mourns Mary Ellen, she’s also mourning their heyday, a time when nuns were lauded for their service: Catholic celebrities in their habits. Now, she feels like a relic in a museum.

“There isn’t a place in our world for them,” Walsh tells me as we walk through the rec room. One nun screams “Checkmate!” at another, and we notice that neither of them are playing chess. However, the Carondelet doesn’t feel like a museum to me. It’s a community unlike any I’ve ever seen; a Sisterhood in the truest sense. They are a coalition of women trying to help each other and humanity, and such a coalition can exist without the looming enmity of God. Walsh says she’d kill to have spent her adolescence in the convent. It’s like an altruistic boarding school from which you never graduate. I understand why these nurses risked their careers to take two nuns to the beach. Foster and Walsh are unofficial members of this club, unholy adjuncts, and that’s what you do for your fellow Sisters.

* * *

1\. Sister Piatra occupied the East Coast campus. The Carondelet wasn’t even purchased until the 1940s. Before then, the land was still orange groves.

2\. Sister Piatra says she’s never seen a naked man, but in some of the portraiture of the crucifiction, Jesus’ scant robes are quite revealing.

3\. In their down time, they have been playing pool on the donated billiards table. Kemper is sure, despite their arthritis, that the two could go pro.

4\. The Sisters are all infatuated with Facebook. When a bevy of laptops were donated to the Carondelet, the nuns had a field day setting up profiles and taking pictures in their habits. Many are still engaged in some hostile “poke wars” with one another. “Ann Margret \[from the East Coast branch\] wasn’t accepting my friend request,” says Sister Josephine, “and I was pissed at her for about a week until I heard she had died!”

5\. They can wear pants now.

.JPG)

.jpg)