“Manhattan Suicide Addict,” (2010-present). Video projection and mirrors. Overall dimensions vary with each installation. David Zwirner Gallery, New York City. photo: David Urbanke.

“Love Is Calling,” (2013). Wood, metal, glass mirrors, tile, acrylic panel, rubber, blowers, lighting element, speakers, and sound. 174 1/2 x 340 5/8 x 239 3/8 inches. David Zwirner Gallery, New York City.

Yayoi Kusama Photographed In New York City In November 2013.

“Infinity Mirrored Room—The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away,” (2013). Wood, metal, glass mirrors, plastic, acrylic panel, rubber, LED lighting system, and acrylic balls. 113 x 163 3/8 x 168 1/8 inches. David Zwirner Gallery, New York City. Photo: David Urbanke.

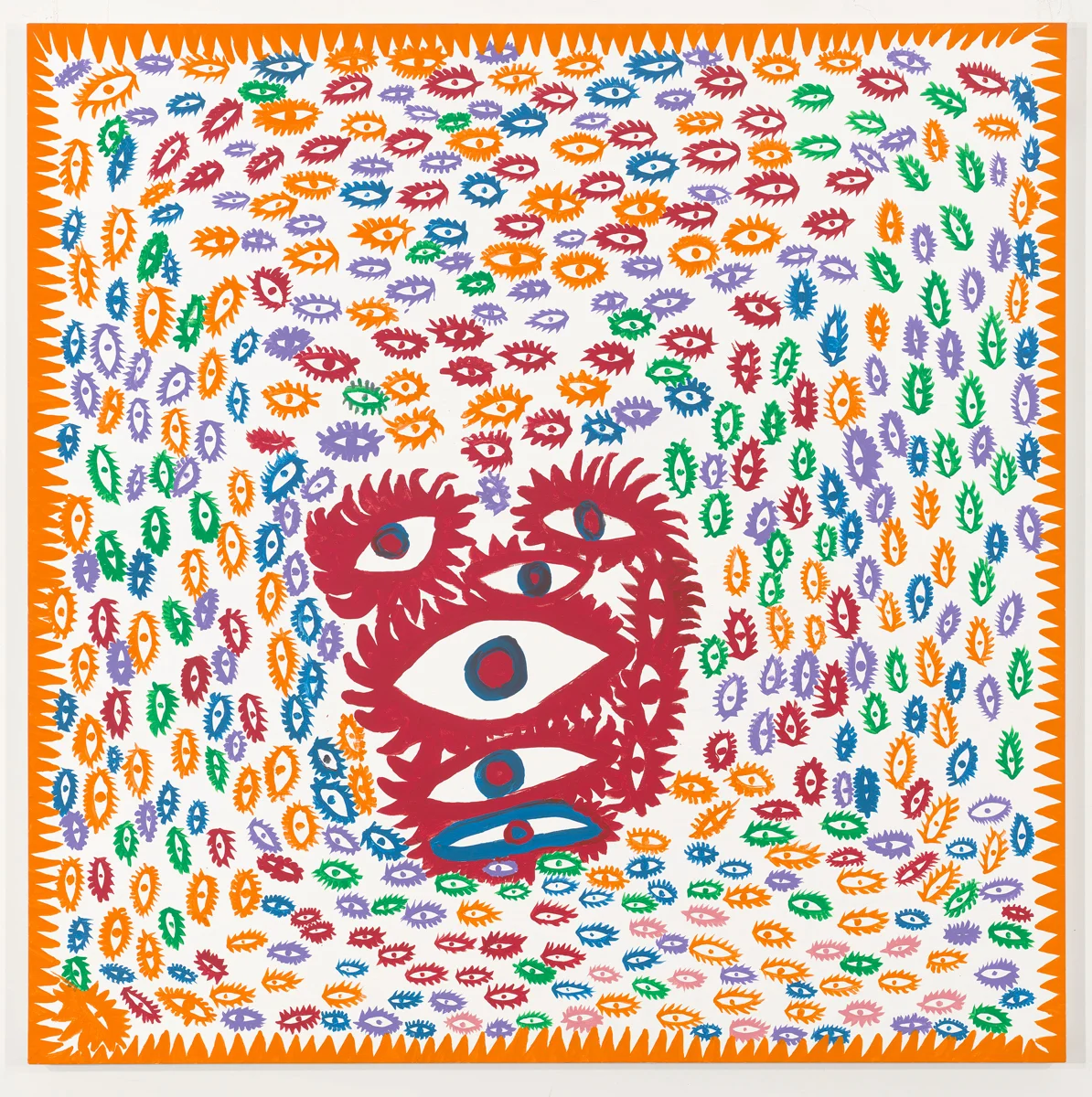

“My Heart,” (2013). Acrylic on canvas. 76 3/8 x 76 3/8 inches. Courtesy David Zwirner and Yayoi Kusama Studio Inc.

[](#)[](#)

Yayoi Kusama

I Was Under Medication When I Made the Decision to Burn the Tapes

STEP INTO AN EMPTY GALLERY AND YOU’LL THINK THE AIR IS ON DISPLAY. With pure white walls and angled track lighting, the atmosphere guarantees that visitors will celebrate whatever resides within it. This environment—surgical lighting, untouched walls, and pristine floors—is standard fare across galleries and museums: a basic facet of art styling that is reliable and undisputed.

But step into any of David Zwirner’s three New York City galleries and that atmosphere is radically altered.

Twenty-seven paintings by Tokyo-based artist Yayoi Kusama line the walls and uproot the stuffiness and silence that is so common in primary-selling galleries. The exhibition, I Who Have Arrived in Heaven, is 84-year-old Kusama’s exploration of death, the afterlife, and her own mental instability.

Kusama is no stranger to major celebrations of her work: This stint at Zwirner follows her vaunted exhibitions at the Tate Modern in London and the Whitney Museum.

But despite the harrowing themes explored in I Who Have Arrived in Heaven, the works remain steadfastly Kusama in style: bright colors, seemingly endless polka dots, unconventional yet impeccably conceived color matching, feminine sculptures, and a heavy dose of psychedelic patterns. The exhibit also has two “infinity rooms” and a video featuring Kusama singing a poem she wrote.

This is not just a collection of a notable artist’s work. The gallery offers a one-way ticket to Kusamaland.

FOR ME, IT WAS LOVE AT FIRST UNBLINKING EYE. Voluminously lashed and wide, simple eyes repeat across the 27 paintings in the Zwirner Gallery. Where René Magritte’s all-seeing eye faithfully details every ocular trait, creating a sense that the viewer is being watched, Kusama’s representations, which don’t even have irises, evoke a sense that the characters in the canvas are in awe or shock.

I become transfixed by her paintings, her process, the fiery-red wig she’s wearing.

Kusama’s paintings, with their stick figures, huge brush strokes, and liberal engagement with the bright end of the color palette, could be seen as childlike. And when an entire painting is simply a mélange of colorful suns, it’s easy to become nostalgic for the days of finger painting and kindergarten curiosity. But each work offers a striking aesthetic and every canvas is so compelling that the longer you look at them the more they mature.

A painting can be lined with faces, yet each differs in features and expression. Astral figures foreground the vibrancy we think we see during that perfect moment of a particularly fiery sunset.

At a press conference held ahead of the gallery’s opening, Kusama is wheeled out and seated in front of two of her brightest paintings. She speaks to the audience frankly and sweetly through a translator.

“It’s a struggle everyday. Now I am in my wheelchair because I damaged my legs and I am going to treatments every day and all the doctors tell me not to do this, that I am doing too much art, never resting, it’s always ‘art, art, art:’ painting, films, sculpture, fashion.”

And she’s right. The woman is 84 and still making works that span huge walls. Her mind is as enviably unpredictable and eccentric as it was decades ago when she wrote an open letter to Richard Nixon offering to fuck him if he ended the Vietnam War. Art is not merely a channel or an escape; it is the force keeping her grounded in this world.

Throughout her life, Kusama has been deeply troubled, seeking professional help since she was young. She has attempted suicide several times in New York, she tells the room of art reporters and admirers. Since 1975, she has voluntarily resided in a mental institution in Tokyo, creating volumes of art within its walls.

“Everyday I am working and creating art: early in the morning until very late at night, sometimes ’til 3 am. I am just fighting for my life,” she says. Kusama’s work often focuses on how we are all facing terrible battles on this earth, and we should strive to obliterate ourselves to become one with the universe or, sometimes, become one with polka dots. In fact, much of her philosophy seems an homage to the theory of reincarnation, samsara, and—ultimately—nirvana.

The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, one of the oldest texts to address nirvana, says “As the snake discards its skin, leaving it lifeless on an anthill, so the soul, free from desire, discards the body, and unites with God who is eternal life and boundless light.” Kusama recasts that “eternal life and boundless light” as colorful blots and celestial hues, but the message remains: corporeal form is a burden, and the ultimate objective transcends anything that can be achieved on earth.

“I think I will be able to, in the end, rise above the cloud and climb the stairs to heaven and I will be able to look down on my glorious life,” she says.

LIGHTBULBS PLUS POLKA DOTS PLUS MIRRORS EQUALS INFINITY. Step into one of Kusama’s “infinity rooms”—360-degree walls of mirrors—and you might first be inclined to take a selfie. The mirrored spaces offer the same photo friendliness and accessibility that made the Museum of Modern Art’s Rain Room such a triumph. Step into the work called “Love is Calling” and you’ll be surrounded by inflated, wormlike sculptures hanging from the ceiling and sprouting on the floor like psychedelic stalactites and stalagmites.

But as the stationary sculptures change color in the dimly lit room, they take on a rhythm and movement. After that, confusion ensues about where you are located relative to the entrance; the eternally refracting reflections of the sculptures begin to muddle reality and image; the looping color shifts become oppressive. Is this what an extended period of time inside Yayoi Kusama’s mind is like? Is there an escape? Step outside and you can’t be sure.

You are first faced with a movie theater-sized screen playing “A Manhattan Suicide Addict,” Kusama’s video project and rebellion against the numbing effects of psychiatric drugs. As Kusama, in her tomato-red wig and matching lips hypnotically chants a poem she wrote, psychedelic patterns grow and collapse behind her, reminding viewers just how wild and troubled she is.

And yet, frank as it is about death—and as dark as it can be thematically—I Who Have Arrived In Heaven offers a resolution after decades of sometimes defiant, politically driven work.

“Every single one of you, I want to share my love and sense of peace with you,” she says.

“I am still full of big hope.”