“Seven Panel Horizontal,” (1973-1978). Charcoal and paper. 180 x 540 inches (X7). Courtesy Mary Boone Gallery, New York.

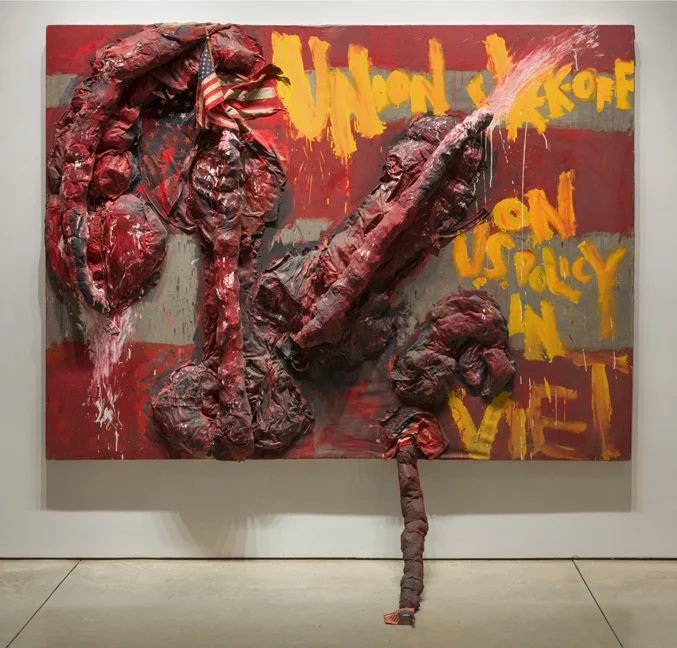

“Union Jack-Off,” (1967). Mixed Media and canvas. 72 x 96 inches. Courtesy Mary Boone Gallery, New York.

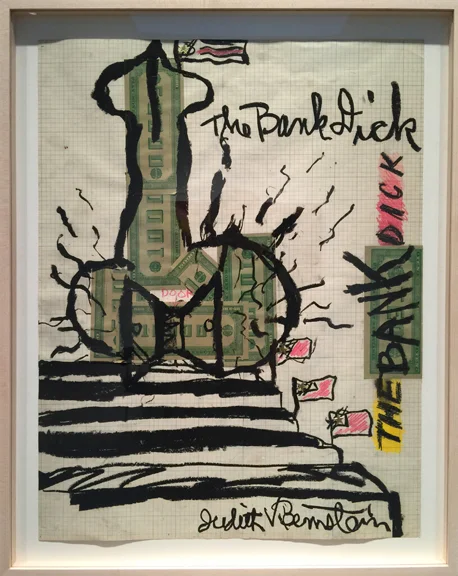

“The Bank Dick,” (1967). Mixed Media and paper. 22 x 17 inches. Courtesy Mary Boone Gallery, New York.

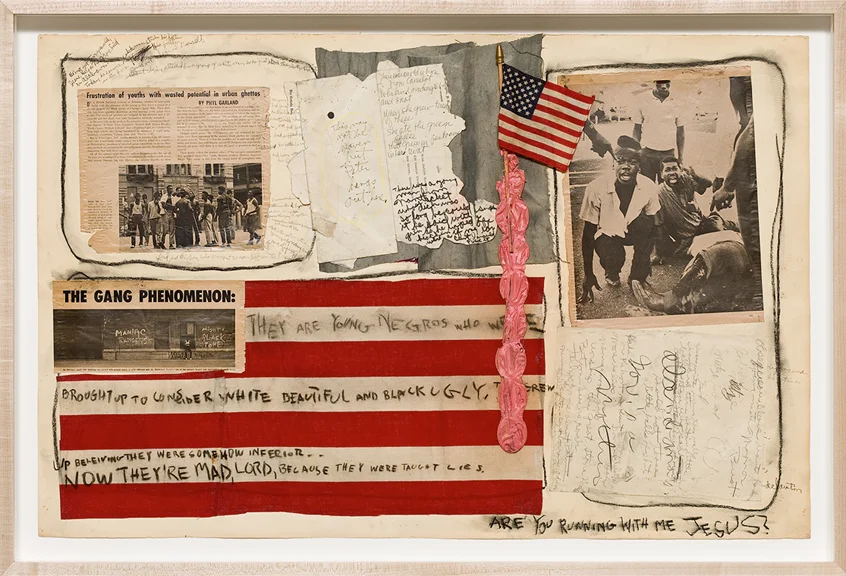

“Are You Running With Me Jesus?,” (1967). Mixed Media and paper. 26 x 40 inches. Courtesy Mary Boone Gallery, New York.

“Iraq Travel Poster,” (1969). Oil Stick and paper. 23 x 35 inches. Courtesy Mary Boone Gallery, New York.

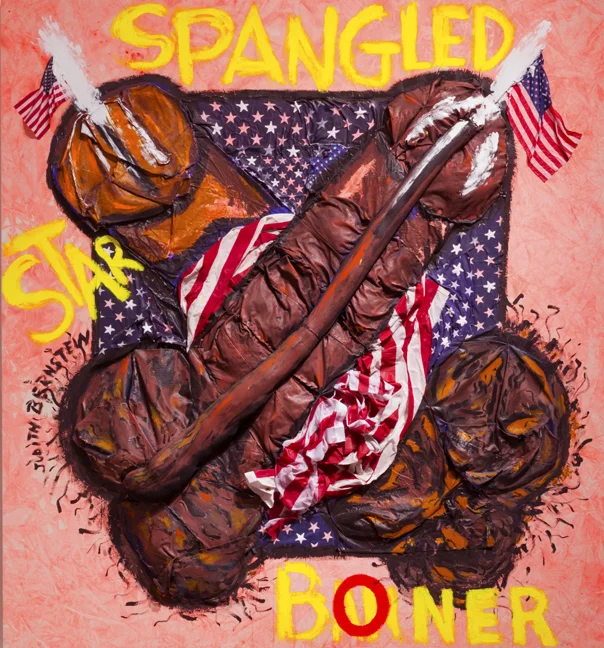

“Star Spangled Boner,” (2015). Mixed Media and canvas. 112 x 102 inches. Courtesy Mary Boone Gallery, New York.

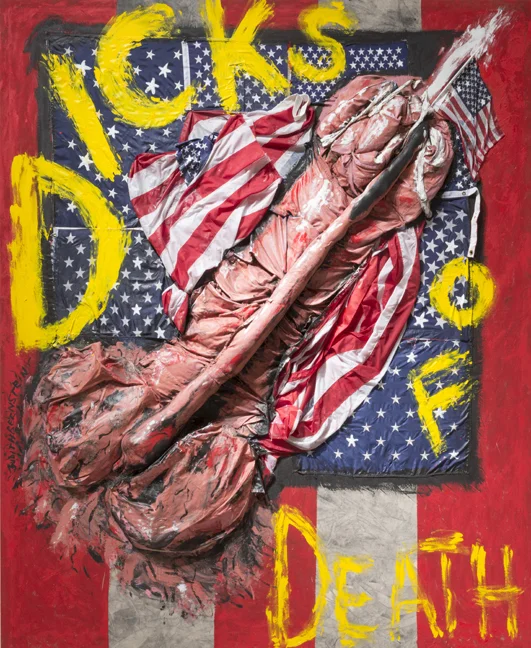

“Dicks of Death,” (2015). Mixed Media and canvas. 112 x 96 inches. Courtesy Mary Boone Gallery, New York.

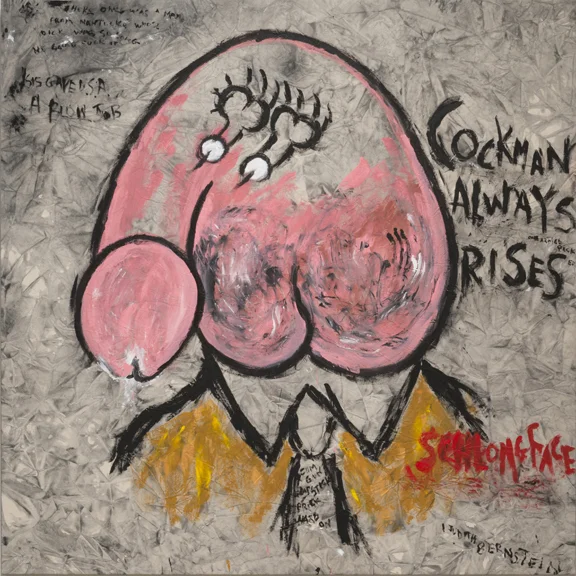

“Cockman Always Rises Gray,” (2015). Acrylic and canvas. 84 x 84 inches. Courtesy Mary Boone Gallery, New York.

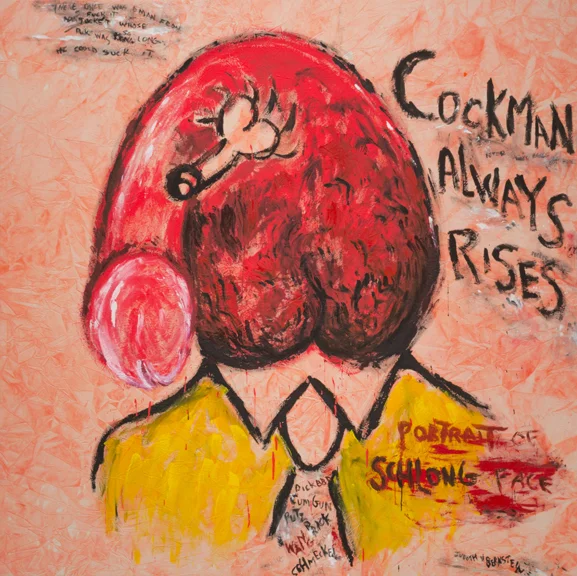

“Cockman Always Rises Orange,” (2015). Acrylic and canvas. 84 x 84 inches. Courtesy Mary Boone Gallery, New York.

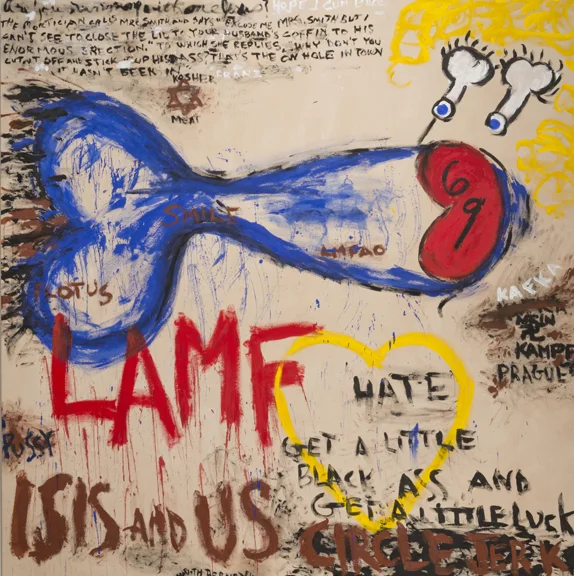

“Hoover Cock,” (2015). Acrylic and canvas. 84 x 84 inches. Courtesy Mary Boone Gallery, New York.

Installation view, Après Ski, courtesy Karma International, Los Angeles.

[](#)[](#)

“And there went Pluto! Gone, gone, gone!”

An Interview with Judith Bernstein

Artist Judith Bernstein, whose work is in the permanent collections of museums across the world, has been questioning the roots of violence and heterosexism since her student days at Yale University in the 1960s. Since then, she has never paused her artistic innovation and activist involvement. A founding member of A.I.R. Gallery in New York, the first female-run cooperative gallery in the United States, and a former Guerrilla Girl, Bernstein has combined a highly skilled career in painting and drawing with an unwavering commitment to feminism. Her work has been censored and attacked by feminists and anti-feminists alike, but she has never been dissuaded, and this year she has the well-deserved honor of exhibitions in the United States and abroad. She is included in the inaugural exhibition of Karma International in Beverly Hills (on view until February 20) as well as a group exhibition at The BOX Los Angeles (on view until February 13), and has a large solo exhibition at Kunsthall Stavanger in Norway (on view until April 10) that will include a significant monograph. I spoke with Bernstein at Mary Boone Gallery in New York, where her exhibition Dicks of Death (military slang for canned beans-‘n’-franks) provided an evocative backdrop for a discussion of art and politics, and even a bit of talk therapy for this writer.

Simmons: Getting into your current and upcoming shows, an interesting counterpart to your work is Virginia Woolf’s _Three Guineas_, in which she suggests that educating women will end war.[\[1\]](#_edn1) Men, it seems, are inherently violent.

Bernstein: You have an interesting point about Woolf. I started doing the _Fuck Vietnam_ series while at Yale in the late 1960s and begin using giant penises. Everyone was chanting, “Hey! Hey! LBJ! How many kids did you kill today?” When I was a student at Yale, I read the brutal novel _Johnny Got His Gun_ by Dalton Trumbo, which is about a man who is left a quadriplegic and without a face after coming home from World War I. He can only communicate by hitting his head against his pillow in Morse code. At the time I thought it was all on the guys. If women were in power, such an atrocity would never happen. I did a drawing that’s now in the Whitney Museum called _Vietnam Garden_ (1967), in which you have tombstones that are actually phalluses with crosses and a star of David.

I, however, don’t feel that way now. The range of gender and sexuality is far greater and far more complex. Now, I think, for example, that Hillary Clinton would be much more pro-war than someone like Obama. In saying that, I’m not dealing with his gender or sexuality because we have so much more nuance now. So, I don’t think Virginia Woolf is correct. But at the time, I feel that we may have had no other way to judge it.

Simmons: That’s interesting that you bring up sexuality alongside gender. Something I’ve been thinking about a lot is how gay men sometimes get a pass for being sexist, even though some of the most sexist people I have ever met are gay men. We believe we’re “one of the girls” or that we can be overly familiar with female professionals. Is it so much about the penis itself, I wonder, as it is about a sexist mindset?

Bernstein: Right, someone’s sexuality or gender does not mean they cannot be sexist. My first experience with feminism was critiquing the guys. Now I’m looking at women, at the “angry cunt.” My mother was extremely angry, and I myself was part of many groups fighting censorship with other artists like Louise Bourgeois. There’s an enormous rage and anger that women have. My mother was not someone who wanted access to the system or a career, but she certainly didn’t want the life she had of being a housewife. I dealt with women’s rage in BIRTH OF THE UNIVERSE/CUNTFACE (2015) and other paintings alluding to the Big Bang. The penises are smaller and revolve around the women instead. It depends on how you look at it. It’s not all men’s fault, and now you have women with more power. Still, it is not equal. I was part of the Guerrilla Girls, but I don’t think women should have equal numbers in all shows or be president of every country. They _should_ have equal access to go as far as they can with their abilities.

Simmons: That brings up a historical question of people’s very vehement rejection of the sexual imagery of Judy Chicago, Betty Tompkins, and Marilyn Minter. These artists have been critiqued by those who think that by focusing on a gender binary, one is reinforcing it. We might be able to revise this for all artists who depict sexuality by looking at your work. Though there is very flagrant anatomy, it seems that it’s not just about that. The subject matter is combined with a purposeful and skilled formal or historical engagement.

Bernstein: I agree with you. I was formally trained in painting and I’m very aware of art’s formal devices of composition, etc. But my work also deals with the subconscious, what you cannot see. I want a visual manifestation of what is interior—of what I want to say—so I’m actually an “image-maker.” I’m also relaying a message with auditory means by using words like prick, dick, and cock-face. I put those things in there, but there’s always a subtext.

For example, I did the enormous screw drawings that are 30 feet long. That’s the subtext of Jackson Pollock, for instance. We feel diminished because of the scale. It’s a combination of war, sex, and feminism. Mine’s bigger than yours! They may own it in a bodily fashion, but men don’t exclusively own the phallus as an _image_. With transgender critiques, people evoke the right to owning their life, to stand where one chooses on a spectrum. The world is also more complex. When I was a kid, we had “Captain Video,” we only had a few planets back then, and there went Pluto! Gone, gone, gone! Everything is so new, like research into black holes, which I have often likened to the vagina as a metaphor. Parallel universes outside of our own once seemed like science fiction.

Simmons: That’s why I feel it is so important to be looking at your work, as well as Betty Tompkins, Marilyn Minter, and Judy Chicago.

Bernstein: Well, we all say different things, but we are lumped together because we are women who are dealing with sexuality. The content of each of our respective practices is different. When you think of other genres, like still life, you think of a whole range of things people have to say with their different styles. All of us say things in our own way. I don’t like lumping it all together because it’s more complicated than that.

WS: It’s an unfair, limiting grouping.

Bernstein: I was put into the category of “sexual” art. Of course my art deals with sexuality, and it does so right in your face, but exists also in a broader context. It’s easy to forget, sometimes, the context of war in addition to gender. In the 1960s, there were many people dealing with war because there was a draft and a large student body that did not want to go to war. Now, it’s allegedly on a volunteer basis, though I’m not so sure about that.

WS: It’s all based on class and poverty.

Bernstein: It’s class-based and related to a lack of options. Disempowered people across the world are forced to use certain tactics, as is the case with ISIS. Don’t misunderstand me; I’m not sympathetic with them. But no one is dealing with the truths and foundations of ISIS, the wars in the Middle East, or nuclear proliferation.

Simmons: In your feminist and activist engagement these global problems, you’re pointing toward something more pervasive and harder to pin down – the subconscious.

Bernstein: That’s exactly right, and it comes down sometimes to the smallest things that provided inspiration for me. Stop the World—I Want to Get Off and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf were directly taken from bathroom graffiti. I would have my classmates watch the door to the restroom and scour the stalls for graffiti. When someone is in the bathroom defecating, you can write whatever you want. No one knows you’re writing it. There are aimless lines sometimes, and people seem to actually go into their subconscious. You have more access to your subconscious, and graffiti is deeper than you might think.

Simmons: The first thing that comes to mind is cruising and glory holes. The public urinal was where middle-class men who had sex with men would go in the early 20th century, while the bourgeoisie could afford the privacy of an interior space. In that sense, your imagery is feminist, but also part of an expanded field of gendered possibilities.

Bernstein: And my work is deadly serious, but in a way that is just humorous enough as to not be obnoxious. It’s like an ejaculation, a release.

Simmons: Not to make it about me, but this reminds me of a terrible breakup. I wrote an essay called “O-face” about how I was sad about this guy and was simultaneously upset that I couldn’t write anything novel or interesting about a breakup. What still plagues me about that relationship is that I never saw him cum, and I realized that ejaculation and the writing process are the same. It’s all, in a way, automatic and replicated indefinitely. Everything has happened before, but you want it to be unique. You’re never going to write something brand new, even if you are a genius like Joan Didion.

Bernstein: When one is making art, those issues have been dealt with before, but this time, they’re being dealt with specifically through you. It’s about you and a larger context of a history of people having that frustration. So, it is actually unique. Sex certainly has been around since forever, but it remains an affirmation of life. You may be mining the same material, but your mind can make a leap that someone else’s did not; in science, math, and art.

Simmons: That connects to the importance of influence and history. There hasn’t been a critical desire to connect your work to that of others, but when I first saw your dicks-turned-screws in the "Seven Panel Vertical" (1973-79) scrolls, I thought immediately of Jack Kerouac’s coke-fueled, queer manuscript for _On the Road_ and Robert Rauschenberg’s "Automobile Tire Print" (1953). Is a feminist iconography an antithesis to the masculinist art history that we currently have? Are you disrupting a history of male artists?

Bernstein: It’s always interesting, and there’s nothing that shouldn’t be explored. Feminists did not always embrace me because I wasn’t being self-referential and always including a vagina. That’s ridiculous, and I think feminism has been transformed into something more all-encompassing, something beyond equal pay for equal work. Women want to be a part of history. Feminists should not limit themselves. Context changes and visual imagery changes. Comparing feminist art to men’s art is worthwhile. It’s akin to how the physics of planetary movement operates; everything is relationship to each other, and nothing can be sustained out of context. I want my work in art history, and it want to be compared to the guys, however, one is never neutral. I am female and I was brought up as a female. But I try to have a broader take on things. After all, we were raised and trained by the history of men. So many things that we internalize cannot be taken out completely, and to take those things out would be to not give women the complexity that they deserve. Once you’ve seen a work of art by a man or a woman, you’ve seen it. You’ve internalized it in some way.

Simmons: And once you have inhabited a body, you’ve internalized something as well, even if that body can change.

Bernstein: Right, there are so many more possibilities now. Before, you were either straight or gay, feminist or anti-feminist. I was hard on the guys for the war, but now I’m holding women accountable too. I have a lot of rage myself, and, returning to what I said earlier, it’s not like I’m saying that such anger only applied to my mother. I know that about myself and I take accountability for it. It gives me the “thrust” I need to embody my own work, so it actually is very positive energy.

Simmons: It sounds like a theme of your thinking is that there is a centrality in your embodiment as a woman and in your artistic materials, but there’s also an awareness of how the uniqueness of your experience can be used in an expansive fashion.

Bernstein: That’s a perfect way to describe it. You often don’t realize when you’re working what you’re moving toward, but then you look back and think, wow, this is what I’ve come up with. It’s a glorious time.

* * *

[\[1\]](#_ednref1) I owe this point to a conversation with Gemma Sharpe, Ph.D. student in Art History, the Graduate Center of the City University of New York.