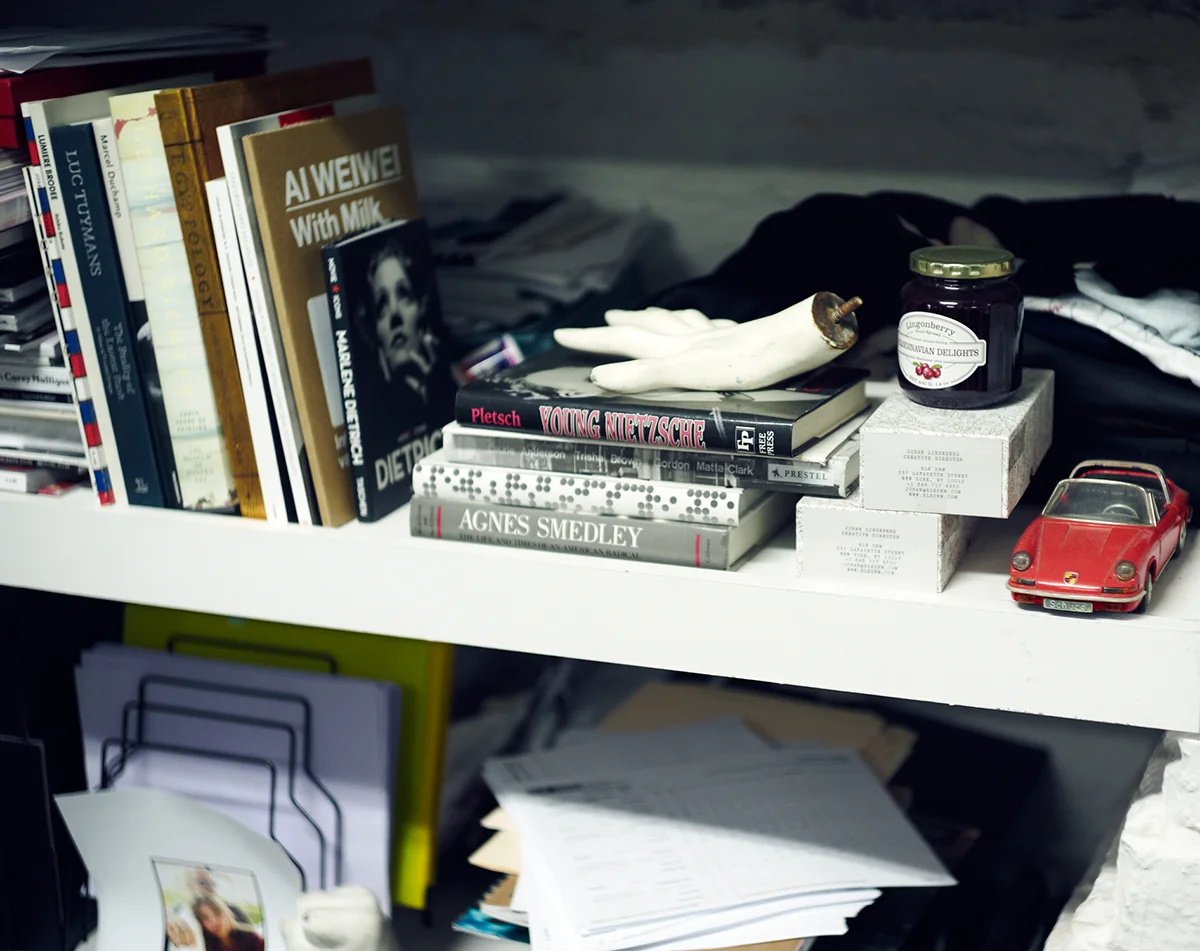

Johan Lindeberg

Johan Lindeberg

Johan Lindeberg

Dustin Yellin

Tyler Lunceford

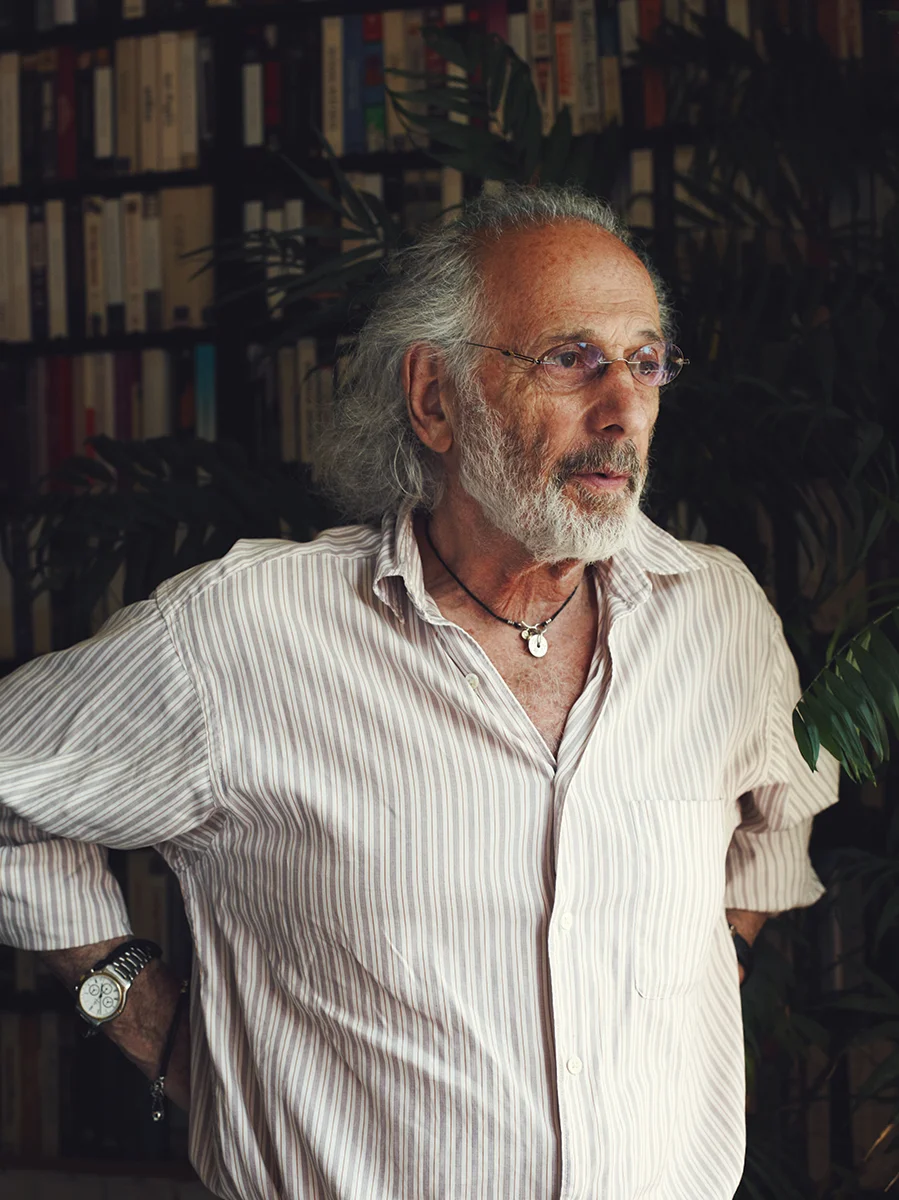

Jann Wenner

Jerry Schatzberg

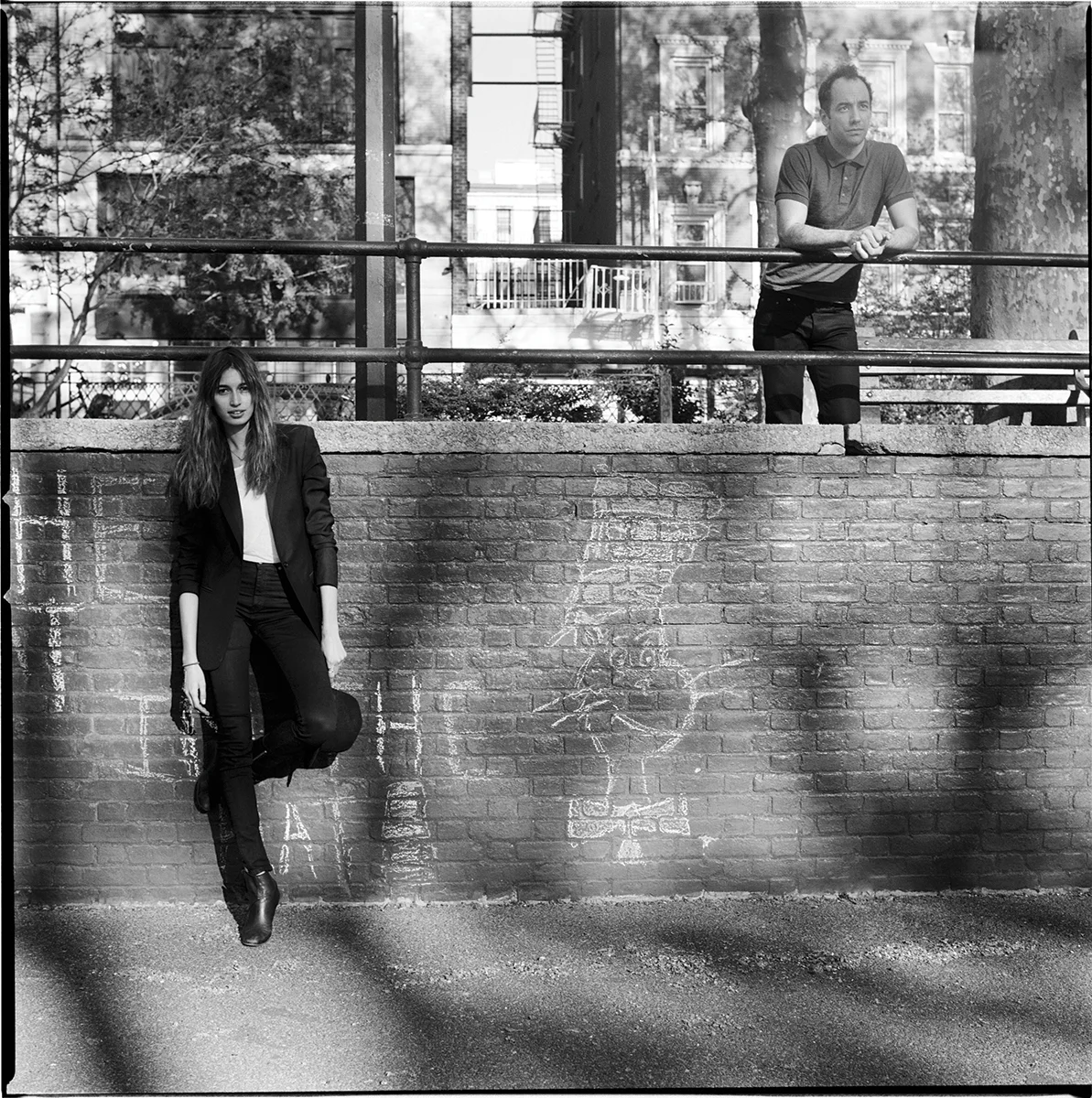

Kenza Fourari

Jann Wenner

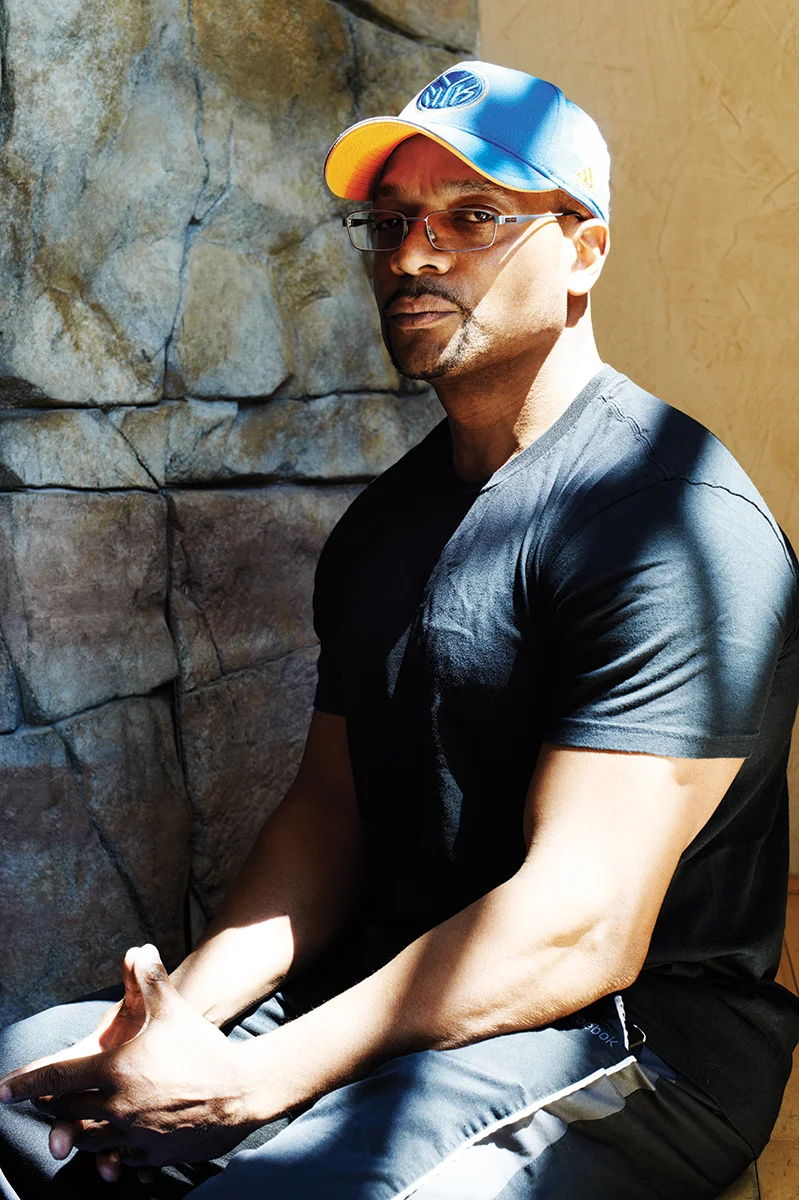

Sam Adoquei

Sam Adoquei

Sam Adoquei

Etienne Adriaenssen

Felix Winckler

Melchior Schöller

Tony Ebanks

Tony Ebanks

[](#)[](#)

Claire? Claire Is a Fat Girl’s Name

A Selection of New York's Modern Influence

**BEFORE READING THIS,** **READ THIS**

Keep in mind, for every question there is always a right answer and one or two not so wrong answers, and that “most people don’t know what to think unless it’s put in context.” So think of these as “contexts” or “lessons in context,” not strict interviews per se, nor strictly profiles of subjects. No, these are more like a series of sketches, recorded by Albert Hammond, Jr., of the band The Strokes, over the course of two weeks at the beginning of spring in New York City. _Flaunt_ followed Hammond Jr. around with a camera and observed as he cut a path through various cultural terrain, which included nine figures of iconic stature: the Designer, the Artist, the Mentor, the Mogul, the Activist, the Startup, the Mechanic, the Filmmaker, and the Muscleman.

But first, we mean by icon “a thing representative” of something—which may also serve adequately as a definition for “archetype.” As an exercise, imagine a student learning to draw shapes—first a circle, then a triangle, square, rectangle, trapezoid, hexagon, and so on. Then imagine a student learning to do almost the exact opposite.

The idea, then, is to reflect what these “archetypes” signify about daily life, sometimes self-consciously and sometimes not so self-consciously. What does it mean, for instance, that for this lesson, we’ve restricted ourselves to a set of nine archetypes? Why do we need archetypes, especially in a climate that ruggedly asserts its individuality and flatters itself while doing so?

Most archetypes enact a beloved theme: a person can become something: a woman can become a “working girl” while a man can become a “bowler.” In the wilderness of professions, there, a few steps ahead of us, is a man who imitates animals. We cease to suppress our laughter. Everything hinges on the significations of the Clown.

Let us reformulate the idea. We become more like ourselves over time, which means _You look more like yourself every day_—but there is also the sense that this sort of feeling produces, to some extent, culture—which is any instance of people representing themselves and their experiences. In a word, whatever is cultural is ultimately historical, and the “archetype” then is this record of that transposition.

**THE MOGUL ARCHETYPE** **AS A CONTRADICTION** _Jann Wenner_

For this segment, look at Jann Wenner, the Mogul. Look now, while thinking of this sentence: _You want to organize your life around an idea._ Good. An image should produce both a picture and an idea simultaneously.

Wenner, along with Ralph J. Gleason, founded the magazine _Rolling Stone_, of which you have heard and likely read—it is a cultural _staple_, like Coca-Cola, Urkel, and Mickey Mouse. Much that can be said at this point is obvious. Instead, let us focus on our terms. What then is this idea?

The word _mogul_ comes to us from either the Persian or the Arabic, and was used primarily to denote the “Mongol or Mongolian; _spec._ any member or follower of the Mogul dynasty” (OED) but has since come to mean (as the Mongols disappeared into history, and so into language) someone who is chiefly powerful, especially in matters of business.

This derivation is plain enough. Power and strength illuminate the denoted like 30 tiki torches. One feels one’s way toward meaning by this light, while the Mogul, according to the blueprint, sits in his business office or suite, at the end of a corridor as long as a Henry James sentence. His enormous leather swivel chair is turned to the vast windows that see over the plaintive squabble of Midtown traffic and toward Central Park. One might say that here, the windows serve as metaphors, but could it be a faint reflection in the pale glass they call master?

Wenner asks, “Were you expecting something more lavish?” and then laughs as we laugh, taking a gander at our environs. Perhaps not, we shrug—but certainly something more staid, more devilishly _sterile_ than the wood paneled walls that comprise the man’s lair. (Where is the marble, where are the Greek statues?) Power has the tendency to refract and distance its wielder from its effects, but our environs at the moment seem incongruously comfortable, almost _intimate_. But we have digressed.

The Mogul, as we understand the term, is fundamentally closed off. We imagine a bristle-headed and ruthlessly capricious tyrant, a man entirely disconnected from the “everyday.” The word is an image, which conjures Charles Foster Kane and Genghis Khan and Rupert Murdoch alike. In the collective imagination, the Mogul is a fearsome, jowly, but ultimately lonely beast guarding a giant vault of power. His passion is this vault of power.

But as we know, blueprints aren’t entirely to be trusted. Wenner would say, _Sometimes you think you’re building a mansion when in fact it is a model doghouse_. Both student and reader of this lesson should keep in mind what a Buddhist would call an “absolutely frozen nothingness.” Wenner’s amicability and good cheer notwithstanding, his willingness to talk is, in itself, a lesson about the fallibility of blueprints. Nor does Wenner have Murdoch’s trademark jowls. Nor is his passion a “vault of power.”

After all, here is our Mogul, smiling, boyish even, showing us pictures from a ski trip to Alaska, or here, waxing poetic about his Instagram relationship with Green Day frontman, Billie Joe Armstrong. He moves rhetorically through his conversation like a fish, but he leans back in his chair and puts his feet up on the table, which hikes up his slacks and makes visible not only his socks but also a hint of calf. From our vantage, it is a nearly hairless calf and well sculpted, with a certain degree of reasonableness. Here all the attention of the student should be focused. What legs have walked the same earth as ours? What sets apart one man from another? Is it:

A) The neat black socks

B) The glossy leather wingtips

C) The show and posture and position of a man entirely comfortable with himself, a man who believes sincerely Bob Dylan is America’s greatest writer in the 20th century, and that to know Bob Dylan is to know _Rolling Stone_.

Heavy is the head that wears the crown, but not always so. Here, the correct answer is: the idea itself. The Mogul is a lesson in a kind of power that comes with being powerful—to say Bob Dylan is the best living writer in America is one thing. To give that statement weight and meaning is entirely something else.

How one chooses to wield that power becomes the essence of that particular Mogul. Of all the archetypes, the Mogul is most in command of his reception.

**WHERE STRIDES THE GENTLEMAN,** **THE DESIGNER ARCHETYPE GOES** _Johan Lindeberg_

The virtue of the Designer is that the spectacle of fashion originates in his own mythmaking—suave, impossible, demanding, dear, articulate, brazen—the Designer detests the wearied and the self-effacing, and champions and deigns the hard-shelled and the autocratic. Though the Designer affects subtlety far better than most, it is the garish type who burns brightest and looks best when outfitted in luxurious fabrics. See for example: the Playboy archetype.

Focus now on a scene of bustle. Here we find Johan Lindeberg in the back of his flagship BLK DNM store on Lafayette in downtown Manhattan; his large beard and round glasses claim our attention. We watch as he gestures emphatically toward individuals racing to and fro, with tape measure and fabric, cell phone and call sheet. These employees, busy at their various tasks, heed him smartly. Lindeberg stands taller than most, and he reminds one of another archetype, the Captain, directing his crew toward the horizon of his vision. And with the Captain, Lindeberg shares the one distinguishing trademark: a madman’s glint.

“I don’t care about any resumes whatsoever,” Lindeberg says. Here, the Designer creates a space from the drama of intuition. “For me, it is all about energy. I am always trying to create an environment where one can get their strength, feel comfortable and confident and be themselves and be able to use their talents—that’s the purpose of life, to use your talents. But it’s hard to find your environment. Here, the energy is so pure. If you don’t fit in, you feel it immediately. You’ve got to be passionate.”

The Designer, by design, burrows into the vice of vanity, and makes of it something scalable and energetic, something to share, like a piece of mom’s pie. Here, self-love is self-mastery, and there are no wrong answers, there are not even questions. You are the test. You are the answer.

**WHAT AN ARCHETYPE** **IS AND IS NOT** _The Muscleman_

In this case, an archetype is a blueprint for a kind of person, both in the negative and positive. This is not a cliché, though it is a little like a stereotype—but not really the bad kind (like a cliché isn’t insulting unless you’re a _snob_ and prefer modern art to movie magic). This is not the proper way of asserting a point, however. Maybe an archetype is a cliché, in the exact sense, but only if you think it is cliché to use a map to get to where you think you want to go.

In the essay “The Butterfly,” Emily Brontë writes, _She threw the flowers on the ground_. Which is the archetype, which is the cliché?

A) Flowers

B) Ground

C) She

In other words, archetypes are like maps, but they’re also like the direction parts on the map, the North, and the South parts, and the mountain areas, and the vast desert areas, though those are in themselves archetypes. Think of a wind swept prairie, or a pumpkin patch. Or, if we fold up our map and put it in the glove box beside the pistol we do not necessarily keep for protection, think of the Muscleman hoisting a cinderblock above his head.

His passion is the act of passion itself. For the Muscleman is a projection that flatters the very idea of projecting, of imagining the self as something else—bigger, better, stronger. He is, in essence, the American Dream. What was once nothing—weak and flimsy _nothing_—is now _something_, chiseled, and fierce.

“People are defensive, and don’t like to be told they’re doing something wrong,” our Muscleman, Tony Ebanks, tells us at the gym. While men curl their weights and stare in the mirror, while a woman stretches her legs on a padded mat, Ebanks expounds the virtue of the Muscleman. “We’re not here to say this or that is bad. What our job is, is to give pointers, suggestions. If you see someone doing something, you don’t go up to them and say, _No, that’s not right_. Instead, you try to be positive, _There’s a better way, let me show you_.”

The student of archetypes would be wise to pay close attention here. The archetype _demonstrates_, it does not tell. In context, the Muscleman archetype promotes the body, and the mortal surface along which we all skate—but this is wisdom that holds true _generally_. His job is to give us an idea of beauty in form—to teach us in the way of the Ideal, that we can become—that _becoming_ is the magic of _being_.

**HOW AN ARCHETYPE** **BECOMES ITSELF** _The Startup, Poutsch_

Like the man holding the patent to a piece of technology, the archetype is used mainly to show that someone has thought of something. Often the term is used to describe something that embodies the pattern of some object’s essence.

Here it would be wise to note almost any kind of thing can pass from closed individuality into a _model_ of individuality. There is no rule governing this transposition except that of repetition. _Repetition may not give pleasure_, Roland Barthes writes, _but it does signify_.

Let us look closely at a man who paints a picture every day but isn’t necessarily held by his peers to be a painter. His paintings are bad, the forms wobble and the heads always look in the same stiff manner to the right. But our would-be painter wears a suit to work and in the evening collects his paper from the stoop of his home. People generally regard this man as:

A) Good

B) A family man

C) Good but desperate

Let us answer the above with another example. Please turn your attention to the Startup.

The Startup is an idea generated in time and space, but depends on a scalable void, the recognition of a momentary problem—one no one else has recognized but understands and sees immediately when pointed out. The Startup, then, is understood in the way a math problem is understood. It is a solution and the question at the same time: it exists primarily to be thought of, and to serve those who encounter it.

Etienne Adriaenssen, Felix Winckler, and Melchior Schöller are the true digital exemplars of this: from Paris to New York, they, together, formulated and formed Poutsch—a web-tool used to qualify what is essentially an infinite amount of data users generate on social media.

A Startup is usually thought of as “disruptive”—in that it highlights a gap in a landscape that is unaware it is full of gaps. The Startup, thus, is the business equivalent of the “invasive species” or the Bratty Child in the Back of Class who knows more than the teacher—the child which does not raise his hand but rather blurts out the answer, often to the chagrin of the educator.

But for our sake, our image of the Startup is of course the flower. We think of roses, of rosy-cheeked children, imagining themselves as part of a landscape that does not know it requires their form and aroma. Did the garden think to itself it needs roses, or did the roses magically appear?

The Startup wills itself into existence as the rose does at the height of spring. Think of Poutsch then, as the qualifier of this will—it is a tool that asks us to reflect, “What does it mean to like something?” and figures the myriad subjectivities of its users through a series of analytical tools, like multiple-choice questions. For instance, what does it really mean, when someone tells you, _Stop and smell the roses_?

A) Roses smell nice

B) Roses are pretty

C) Roses are all around us

**WOULD PICASSO BE** **PROUD TO BE WARHOL?** _The Artist, Dustin Yellin_

The Artist participates in the same mode as the Worker: Usually made grimy by the material or substance the Artist prefers to work in, he or she stands a little to the side of the current moment, one eye winking, the other half-closed or rolled back. Their genius huddles around the use of gesture and form to accomplish what philosophy and religion cannot.

Here, the Artist, Dustin Yellin—he is not quite big, physically speaking (he is, in fact, average sized), though he makes very large and physically compelling pieces of art, these being collages set into layer after layer of glass. Imagine for a second your favorite painting; now imagine that painting stretched forward and backward and from side to side in space and then held there, in mesmerized abeyance, in a glass cube you can walk around. How would your favorite painting change if you could view it from every angle?

Yellin’s major project at the moment is perhaps the most three-dimensional of all: the creation of an institution. This is either:

T) True

F) False

In Red Hook, in a refurbished machine manufacturing facility built in 1866, Yellin has begun Pioneer Works, a center for Art + Innovation, and the goal is to create a home, free and open to the public, for different practices—from sketching to microbiology to computer programing.

“Ever since I came to New York, from California, I thought—well, I was a high school dropout, and I didn’t go to college, but I was lucky when I came here, to meet all these different people in a community—some of them were painting, or making music, or making sculptures—it seemed like, _Shouldn’t there be a place like this, where all the different disciplines could come together_?”

The Artist uniformly starts with the conjecture, _Should_—_Should I present to the world my vision as I see it?_

Because we are outside, because we are sitting on a grassy hill, and there are dogs running about, and a kid with a messy ponytail is grilling mushrooms, because while other people work and tend to the (Hurricane) Sandy-ravaged garden and green space, Yellin pauses and looks around, before adding in his nasally tone, “It’s like if you took a lot of LSD and said, _What’s the greatest possibility for a cultural center, for a cultural point of contact_—that’s the fundamental ethos behind this place.”

This is his Pioneer Works, inside, and outside—a vision of the word, _Should_. It is a beautiful day. Shouldn’t life be beautiful? Shouldn’t we go to the movies? Shouldn’t we make music, and art, and community? Shouldn’t we share it?

**A QUESTION THAT PROVOKES THOUGHTLESSNESS** _The Mechanic, Tyler Lunceford_

Let us look at the man in the plaid shirt and jeans. On his head is a yellow hard hat, tilted back, almost casually. But the expression on the man’s face is anything but casual. He stares intently at a rather large scroll of paper. What is he looking at?

A) Building instructions

B) Building plans

C) Blueprints

The correct answer is: _You build an idea generally held about something from the ground up_.

It’s perhaps no different than you, a small thing, all teeth and soft sinew, a little kiddie, cross-legged on a carpet square among other little kiddies. There is Mrs. Joachimsthaler standing at the front of the class in her big skirts, her shoulders slightly rounded forward for the massive dugs beneath her white ruffled blouses. You remember the day she asked what you all wanted to be when you were “grown up” and looking for work.

Her eyes darted around the classroom like scurrying field mice, and you remember thinking not necessarily of particular people, but of the types people become.

A football player.

A piano player.

A lawyer.

Our Mechanic, Tyler Lunceford, would not have raised his hand—and would not have for a long time after that, while fathers, teachers, and the like, insisted he become something, raise his hand, say something.

Something? But what?

When an archetype who doesn’t know he is an archetype enters the world and is asked what he is, who can doubt the power of language, of one’s ability to say: “I am becoming myself.”

Inside the Mechanic’s shop there are bikes, some half-built, others gloriously intact, ready for purchase. The aroma is oily, but powerful, and redolent of labor. From a stereo, we can hear rock ‘n’ roll music. Lunceford uses a pink rag to wipe his hands clean before shaking ours in greeting. We should focus on the firmness and diligence of this grip. A good student of archetypes will recognize there is an infinite certitude of being in the essence of a firm handshake, because you know you are being held. Thus, the handshake becomes a conversational segue, and we discover at the end of its limb, the reason for the Mechanic’s being.

“I actually was a customer at this dealer in Oregon, and whenever I went in there, I was just really excited. I met everyone and made friends with all the guys. One day the manager asked me what I did and I told him, I’m a horseshoer, I’m a farmer, I studied marine biology in college, but then I paused and said, ‘I don’t know. I just do all kinds of stuff.’ And he said, ‘Well, we’re always looking for people who fit into our family here, and we have a spot in service.’ I had no idea what it would entail. I was just moving to Portland at the time, so I thought I would give it a shot.”

Saul Bellow writes, _A man’s character is his fate_. Keep this in mind as we transition into our next archetype.

**AN ILLUSTRATION BY WAY** **OF EXAMPLE** _The Activist, Kenza Fourati_

Think of a man thinking to build a house. He does not think, _What is the meaning of the word house_? Rather, he begins his endeavor by finding himself a door. Likewise, the Activist.

The Activist does not seek to become an Activist but is rather _thrust_ into the position of becoming. Situations conspire to make of us agents and actors when rather nothing done at all would seem the preferable course (most prefer nothing to something). However, there is something more in history than “mastery and servitude” and the struggle to affix meaning to syllables. There is a small contentment and a great affection for the shapes of clouds, the laughter of children, and a well-oiled ball bearing.

A model before an activist, Fourati was born in France but raised in Tunisia, and is the first female of Arab ethnicity to pose for _S.I._—that is, _Sports Illustrated._ What is important is that this is important enough to include in her Wiki entry.

Alas, History, that prim old thing, decides its own importance. When the events of the Arab Spring began in 2010, she was in the States, and like most, watched or participated in the events through social media. However physically distant, she became an unlikely symbol of the Spring’s impromptu ethos.

“A few months after the revolution, two Tunisias had emerged. One, littoral and secular, and the other one, inside the country, and much more conservative. Being very proud to be part of the most progressive Arab nation, I chose to fight against those who were questioning women’s rights. A young female artist used my body as a canvas and wrote a Victor Hugo poem on me. Through the human body, we can praise love and acceptance of the other. But then a local magazine put it on its cover, and my image and the poem became a major and violent controversy in the country. I chose to stay silent, observing. But what I noticed was—from the defenders to the reactionaries—no one stopped to really read the words. All they saw was the image, never the meaning.”

Camus would write, _He that dedicates himself to the house he builds, dedicates himself to the lives of his neighbors_. The Activist challenges us to see the world as one Home, on both sides of a fence no one was aware they were involved in building.

**IF THE WORLD IS NOT A HOME** **THEN IT IS AN IMAGE OF HOME** _The Filmmaker, Jerry Schatzberg_

The Filmmaker trades and traffics in archetypes, knows exactly their proportions, as the chemist does the measure of a beaker of hydrochloric acid. But when archetypes are strung together, are made to act in an arrangement or sequence, the archetype becomes dislodged from its foundation and becomes other than itself—becomes a part, rather than a whole.

It is as though the blueprint is crinkled into a ball and tossed out the window. The Filmmaker is a rebel of archetypes. He is also a window.

Sometimes the lack of inspiration is inspiring just as sometimes not having a view is a view in and of itself. A good student would pause here.

True or false?

Jerry Schatzberg opens the door to his apartment. According to the blueprint, this apartment is on the Upper West Side; there’s carpet, somewhat dingy, and classical music playing; a faint aroma of cat or old newsprint or something of an ointment for joint pain; piles of books, scripts, notes scattered throughout; an old piano; strange and somewhat off artwork on the wall and a cluttered desk in front of a row of three windows. Schatzberg’s voice—because he is old—is a reduced and gravelly whisper, but possesses the rhythm and cadence of the street; it is an old Jewish New Yorker’s voice, with youth’s twinge.

This voice, as though beside the man, directs us to sit on the sofas arranged around a large coffee table. He sits similarly, but with an idea, he stands again, and asks if we want coffee. We want coffee, and so coffee is brought to us.

Between the glasses at the end of his nose and his eyes is the screen on which the Filmmaker assesses all the uncombed and wild malice of humanity, where its profound kindnesses and wit and drudgery find its form. Again, it is impossible to know what a man’s image of the world is unless he captures it and shares it. The Filmmaker archetype fulfills two functions for culture:

A) He shares representations

B) He hoards representations

But is what the Filmmaker considers beautiful the image itself or the content of the representation? Does the world always neatly and nearly break in half along these lines?

If culture has created all these institutions and modes for debating the beautiful, we suspect it has not done so because it knows what is beautiful, but because it has no idea what beautiful is. Instead, like a giant waving hand, it invites conversationalists and their pet conversations. Here, into the foray, enters the Filmmaker, tasked primarily with challenging people to determine for themselves the meaning of this or that or the other thing.

For example, the student of archetypes should study the opening scene of Schatzberg’s landmark film, _Scarecrow_.

It begins with a wide angle shot of a man, dressed in rags, walking down a barren hill toward a fence—which is also toward the camera, or viewers.

At the far edge of the barren hill is a single row of gnarled trees, while the sky above is dark, threatening rain. This is a static image, but it signals a sequence when the shot cuts to an observer, a man perched in a tree, watching as the man makes his way down the hill. Soon the man coming down the hill is at the fence and is struggling to work himself through the wires that comprise the fence. Finally, the man slips through and dusts off his pants. The man in the tree asks, “Are you okay?”

The man does not respond.

True or False: The opening scene is a metaphor.

As a violin concerto plays softly, as we drink our coffee softly, as the light softly winks through the blinds of the window behind us, Schatzberg tell us, “I don’t think anything is really off limits. I got criticized for a photograph I did of a dwarf. I didn’t think it was _awful_. I was standing outside of Christian Dior, and I was on assignment, waiting for a model to go take a few pictures, and I saw the window, and I noticed it was very rococo, and I took a picture of the window, and it just seemed empty, devoid of humanity. So I figured I’d take a picture of this man walking by, and he passes by and I take the photo. But then up the block I see this dwarf, and I figure, _I gotta get it_. She’s walking down, and she passes the window, but then she stops and stands there, and she’s looking at the shoes the same as any other woman would, and I loved that.”

**AS A CONCLUDING ARCHETYPE** _The Mentor of Conclusions, Sam Adoquei_

One day may be our last, and on that day we will be given a test, and on that test will be questions, hard to answer questions, and most of these will involve You, the Reader, and the word Why, and this word will break you open, as the bus that is about to hit you speeds up, as the engine on the right wing of the plane you’re on bursts into flame, as the lone gunman mounts the stairs of the clock tower on your campus, and You’ll ask yourself, Why are you even taking a test, what did all this time I spent really amount to—a few questions, a few wrong answers, a few chuckles—and you will not be wrong to want to start crying or laughing, or to ask the Test Giver if you could have more time to think through the final question. For this is what is expected of you, the Reader, the Archetype, this dumb disbelief in the face of Hard Truths.

Sam Adoquei sits on a folding chair in an empty room. The story he is telling is the life of Anicius Manlius Severinus Boëthius, the philosopher hired by the Romans to clean up the corrupt Senate, and then sentenced to death for doing his job—a little too well.

What are these hard truths?

Boëthius in his jail cell asks God, “If you are a just God, why are you allowing me to suffer, why are you allowing me to die? I have been good all of my life, why is this happening?”

In Adoquei’s version, everyone who does good suffers for doing good. He says, that is why You, the Reader, are here.

_To learn_.

END OF LESSON