F L A U N T

.jpg)

Charlotte Rose didn’t so much enter the art world as ambush it—with a wink, a cigarette pack, and a Shakespearean soliloquy tucked in her back pocket. A self-taught artist, she swapped literature seminars for oil paint and spray cans in the strange crucible of lockdown, skipping both academia and gallery gatekeepers to stage her own debut on Instagram. Instead of training, she chose subversion: collaging history, branding, and literature with the irreverence of a writer scribbling in the margins. Today, her work hangs in the same London rooms once haunted by Freud and Bacon. Surreal? Certainly. But Rose would probably just shrug and quote Vonnegut: “So it goes.”

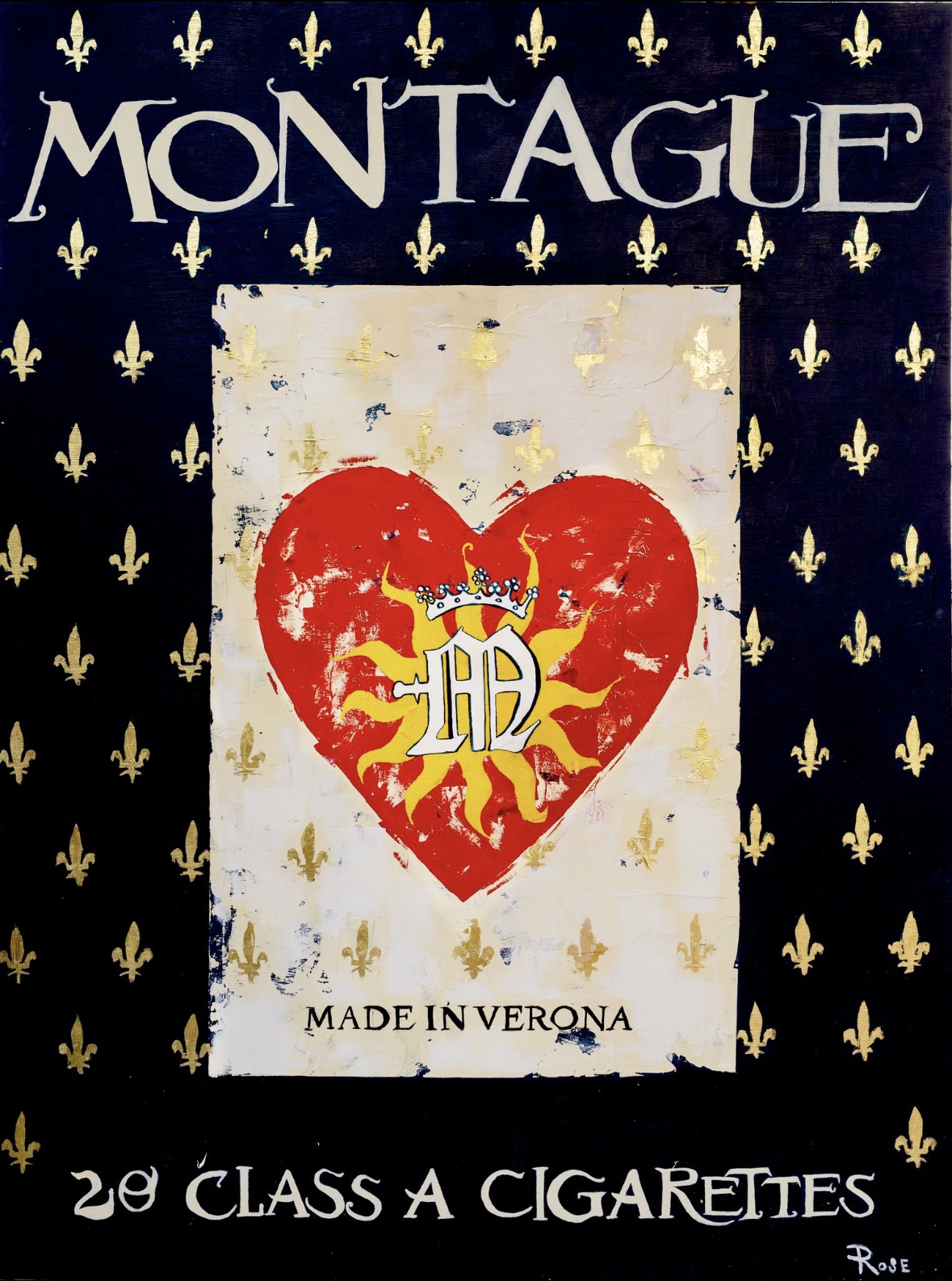

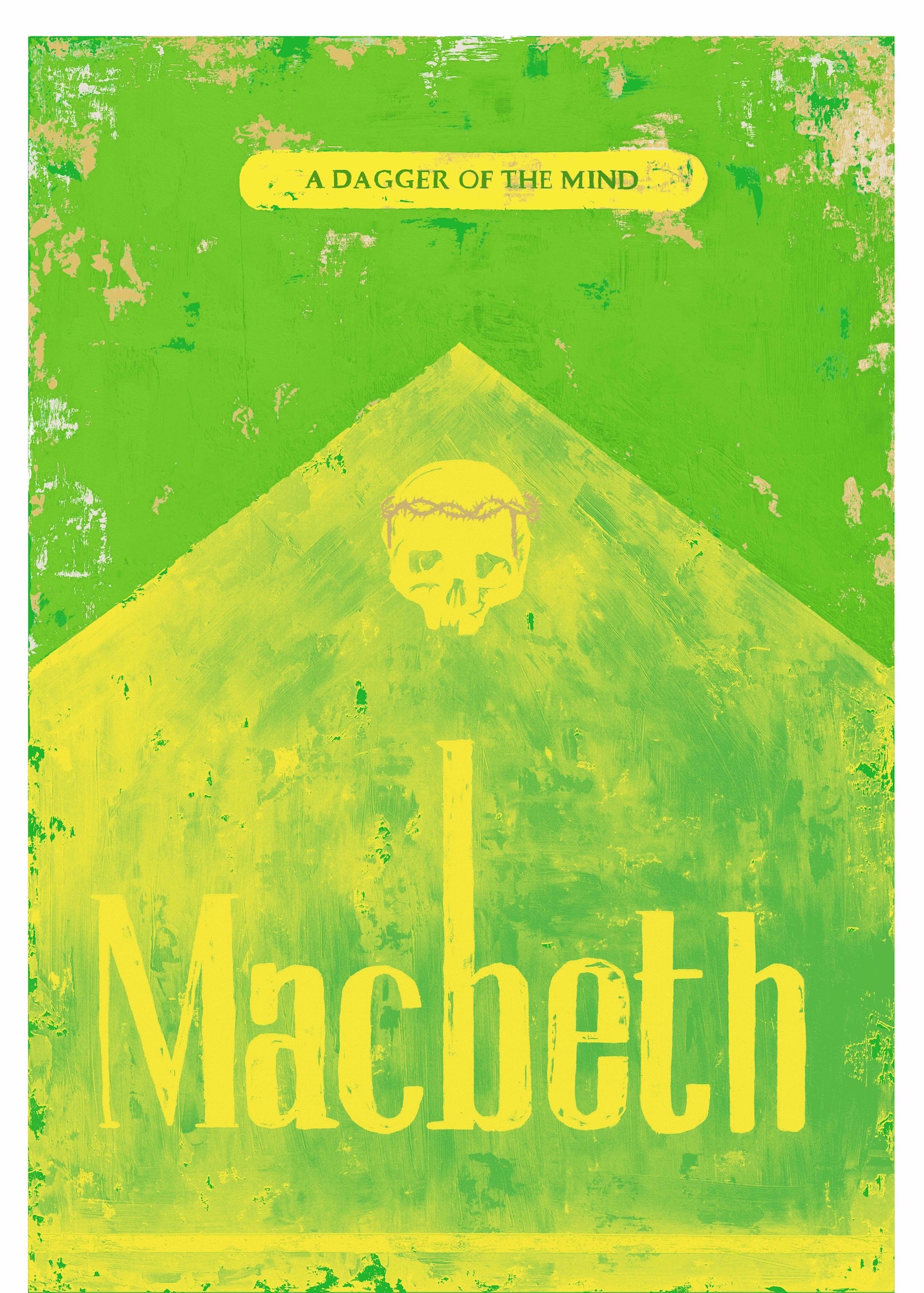

Her origin story reads like a bildungsroman with equal parts cigarette ash and Shakespearean ink. Raised in the orbit of art (her mother a painter), Rose resisted the obvious inheritance and fled instead to books. Because what’s more rebellious than rebelling with literature? Shakespeare, Bukowski, Vonnegut, McCarthy: her canon is bawdy, brilliantly ill-mannered. She once studied Macbeth by day and, years later, rebranded him as the figurehead of a fictional tobacco empire by night. For Rose, a cigarette pack is never just a cigarette pack—it’s a stage, a billboard, a Trojan horse for power, persuasion, desire, and nostalgia.

If Pop art once worshiped consumerism, Rose teases it with a distinctly English literary kink. And if Warhol silk-screened the soup can, she gilds the Marlboro pack, laces it with allusions, and sets it shimmering in 24-karat gold leaf. The collision is deliberate: centuries-old reverence crashing into disposable Americana. In her hands, the cigarette carton—the most masculine-coded of objects—becomes feminized, intellectualized, satirized. It smolders with wit as much as with nicotine residue. What Camel and Newport once promised in cool rebellion, Rose reframes as the tragicomedy of modern consumption.

As she prepares for an upcoming duo show with The Connor Brothers in Austin, Rose once again aligns with artists who understand satire’s slick power. Whether she’s painting a cigarette pack, a poker hand, or a Tabasco label, Rose is ultimately painting us—our habits, our histories, our hungers. And if that’s the dream Charlotte Rose is selling, the punchline is clear: we’ve already bought it. To further peel back the layers of her practice, FLAUNT caught up with Rose over Zoom in her paint-splattered London studio—where the conversation, much like her art, was anything but filtered.

.webp)

You taught yourself to make art during lockdown, bypassed the gallery gatekeepers via Instagram, and now you’re showing in spaces once occupied by Freud and Bacon. Does it feel surreal to have pivoted so quickly?

I'm almost pinching myself every day that I'm able to do something that I love. Every day is kind of a joy—creative, different, and fun. It did happen quite fast for me, but I committed everything to it at the same time. So, yeah, it's definitely surreal.

You initially resisted following in your mother’s footsteps. How did you find your own way back to art—and does being self-taught give you a different kind of freedom?

I've always had a resistance against being told what to do in any sort of way. I didn't do super great in school—if they asked me to read one book, I’d think, “That's rubbish. I'll read whatever I want to read.” I was always interested in textiles or painting, but never really pursued them in academic ways. I was pushed toward literature because it felt more academic, and I wanted to be a writer. I guess that's like the most creative thing you could do under the umbrella of English, and I wanted it to be different from what my mum did.

When the lockdown happened, I decided I was just going to paint for fun. At the time, my partner was an artist, and they had all of these paints, spray paints, and anything you could think of. That's who I was with in lockdown, so I had access to all these materials, and I thought, let's just do it.

Your background in English literature clearly runs deep. Which authors or themes do you keep returning to—and are there new ones you’d love to explore?

I love Shakespeare. That's the one that I think works with my work so well. I studied literature at university, and Shakespeare was something that I focused on quite a lot. I liked the tie to my English and my Scottish roots as well, with Macbeth, and I found it interesting to play with those ideas. Going forward, I'm not sure what I would like to do because it hasn't happened yet. I always just do it. But I'm always reading, and I'm always trying to find something new, so I'm sure it will come to me.

I just did a show with Maddox Gallery in Mayfair, London, and they actually requested for 20th-century literature. So, I did Bukowski, “Blood Meridian,” and Kurt Vonnegut, who is one of my favorite writers. Picking out little themes from each book and applying them, particularly Bukowski, I found, worked really well because he had that kind of pessimistic, angsty flair to his work. My favorite poem of his is Style: “To do a dangerous thing with style is what I call art.” And to me, that works so perfectly with my cigarette boxes.

Your work is bold, witty, and layered with literary references. In “Shakespeare Tobacco Company,” you draw parallels between Macbeth and Big Tobacco. How did that series come together, and what does it say about power and persuasion today?

I don't know where it really came from. It might have just come from the idea of using the word Macbeth on a Marlboro packet because it worked so well with the ‘B’ aligned in the center and mimicking the word Marlboro with the ‘M’ and the ‘B.’ I liked that image, and I also liked the parallel: in Macbeth, the king rises to power, becomes power-hungry and jaded, and turns against his friends, which ultimately leads to him killing people. To me, that tyranny and that story mimics the idea of big tobacco, where it was like, “I'm your best friend. Smoking is really good for you. Smoke is really cool.” But then it rose to a point where they started telling lies and things came out about how it maybe wasn't so good for you. I found this quite a nice mirror image.

You often reimagine cigarette packaging—a deeply masculine-coded symbol—and infuse it with a distinctly female, literary intellect. Is that intentional subversion part of your mission?

It wasn't particularly intentional at first, but I do like the idea that the work that I produce is masculine because I'm quite feminine as a person—I dress girly, and I'm not a masculine energy. But for some reason, I just create artwork that I think looks sick, and it just happens to have a masculine vibe. I also believe I was drawn to all of that vintagey 1960s/1970s Americana branding and Mad Men-esque stuff. That really inspired me, and then I kept on rolling my first ever cigarette pack.

I actually got the idea to paint it because I was watching True Detective, and Rust, played by Matthew McConaughey, just sits and chain smokes a Camel cigarette and has the packet next to him. As I was watching it, I was thinking it would be really ridiculous to kind of paint a huge cigarette pack and have it the whole length of my wall. And then I did just that.

You’ve been described as a British Pop artist in several interviews, but how would you describe your aesthetic in your own words?

I would describe myself as a British Pop artist. I enjoy the satire of it all and how silly it is. I'm always looking to see how I can play around with things. I look up to artists such as Pauline Boty, who was a Pop artist from the 60s. She actually passed away when she was 28 years old, and she was really young, but she made a proper stride in the British Pop Art Movement and then kind of faded into obscurity. Then Peter Blake emerged and shouted her name from the rooftops, and all of [Boty’s] artwork got taken out of archives and given a new lease of life. She was a model and an artist who used her sexuality to promote her artwork. I feel like I'm right there, mirroring their careers.

You also come from a modeling background. Has your experience in fashion shaped your awareness of branding, image-making, or how we package desire?

I started modeling when I was 18 years old because it was a way to initially make money. But then I fell in love with it. I actually really enjoyed the creative process and learning from creatives who were really high in their game and doing something that they loved.

I've also gained quite an awareness of things—how to make things look good on social media and what works for making something go viral. That is very intertwined with my artwork because my art is about branding. I'm advertising myself as an influencer and as a model, and I guess that just gave in a subconscious way. I was taking in all of these things you need to know as a model: you pose in a certain way, you know your angles, and you know how to create this image or a character. I simply applied that idea to social media to create the Charlotte Rose character, which is quite sexy.

You’ve said you’re fascinated by the way companies “sell a dream” through patience and storytelling. Do you approach art in the same way?

My art is very nostalgic, so I'm really aware of the little anchors in people's lives. I don't just paint cigarette boxes, but that is a subject that works for me. Anything I paint—Tabasco boxes, playing cards, poker chips—is really nostalgic. Why cigarette boxes work is because if they're on your person all the time. It’s a little thing that is always present, and you attach an association with them.

Cigarette boxes were trying to capture this dream and sell it to you, but then I'm reappropriating that, taking the nostalgic element, and selling it as well. If someone sees one of my paintings of a Newport cigarette box, they might think, “Oh, my granddad used to smoke those,” and they are instantly reminded of that memory. And with the added literary element, I think people have a connection with certain stories or authors, or even certain phrases and books. My favorite phrase from a book is Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five, “So it goes,” and the last line of the book is, “Everything was beautiful, nothing hurt.” I used that in one of my paintings that's going to Texas, and I think these sort of anchors of nostalgia are really important for what I'm trying to capture.

You’re returning to West Chelsea Contemporary in Austin for a duo show with The Connor Brothers. How did that collaboration come about, and how do your high-literary Pop sensibilities meet their slick satire?

I’ve actually known The Connor Brothers for years because I modeled them when I was 19 years old. I was just a little young model and didn't even speak to them. All these years later, I did a show in Miami about two years ago in Windward, and the man who owns West Chelsea Contemporary, Gary Seals, saw my art there, really liked it, brought me into the show in Texas, and just put me alongside them. It was a complete accident that we were put together. It has this Pop arty, nostalgic, kind of 60s/70s edge to it. They work together nicely, and they're not in competition with each other.

You’re showing new work at the Colony Club with Jealous Gallery—a huge moment. What are you exhibiting, and what does it mean to you to enter this historic space?

I just wrapped up my three-week residency there, and it was an honor to be asked because it's this British institution that holds so much history and weight to it. The people who have been brought in recently have been asked to revive it and give it a bit of fresher energy. They are all really interesting and cool artists, and they’re keeping it alive.

With Jealous Gallery, I made a collection of new screen prints, and they are mono-printed. The mono-printed element means that I paint straight onto the screen. When it’s pulled through once, it produces a unique artwork, which is then layered with the screen-printed stencil. It’s a uniform thing, but each one is slightly different. I was just experimenting with Jealous to see new techniques and how to elevate my work in a different way. And the Colony rooms were just an opportunity to showcase it, which was really nice.

When you’re creating a screen print, how do you know when the idea clicks—when the brand, quote, and layout lock into place?

All my screen prints are reinterpretations of original paintings I’ve created. For example, the Macbeth piece began as an oil painting. That work stands on its own, but I then reinterpret it so the screen prints carry the same concept in a new form. The painting establishes the idea, and the screen print rearticulates it through a different form.

Do you have a favorite piece you’ve created this year? What makes it stand out to you personally?

I’ve painted more than three pieces, but there are three I really love for Texas. One is a hand holding Lucky Strike cigarettes with the words “Lucky you.” Another is a hand holding two aces, also captioned “Lucky you.” They're all in 24-karat gold as well, so they're super shiny and luminescent. Even if there's no light coming into the room, they are creating their own light.

The process of gold leafing is so ancient, and gold leafing has been the thing since the Renaissance, even pre-Renaissance. I like the idea of this Pop arty, new technique, screen printing. It's all very new and then just like gold leafing, which is so old. There's something quite nice about the melting of these two techniques.

What’s next—any additional dream collaborations, new mediums, or projects we should keep an eye on? Are you reading anything now that might sneak into your next series?

At the moment, I'm really reading a bit of Joan Didion. I think I should do something with her, and one of my favorite books is by Patti Smith. I need to get some more female authors into my work, so that would be really cool. Work-wise, everything comes together really quickly. They'll ask me about deadlines for shows three months in advance, so I’ll do the show and then end up waiting for something else to happen. I haven’t got anything lined up at the moment, but I just painted the window display for Selfridges in London. Opportunities like that keep popping up—quite commercial projects, which are really fun. I’d love to do more in the States. I really enjoy being out there, and I love Austin, Texas, so I’m excited to go back.

.jpg)