“Pila Bench,” (2013). Laquered wood and folded black inox. Courtesy the artist.

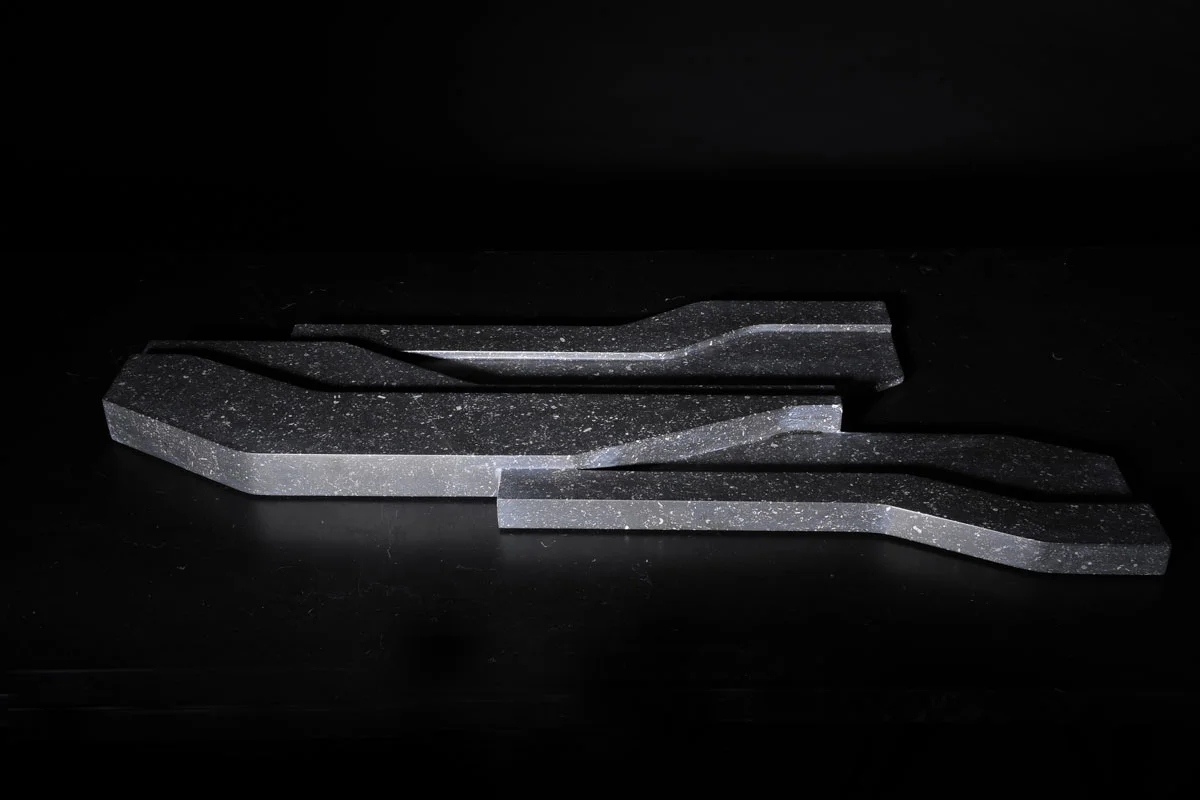

“Landscape Sculpture,” (2009). Little Belgian Granite. Courtesy the artist.

“Landscape Sculpture,” (2009). Little Belgian Granite. Courtesy the artist.

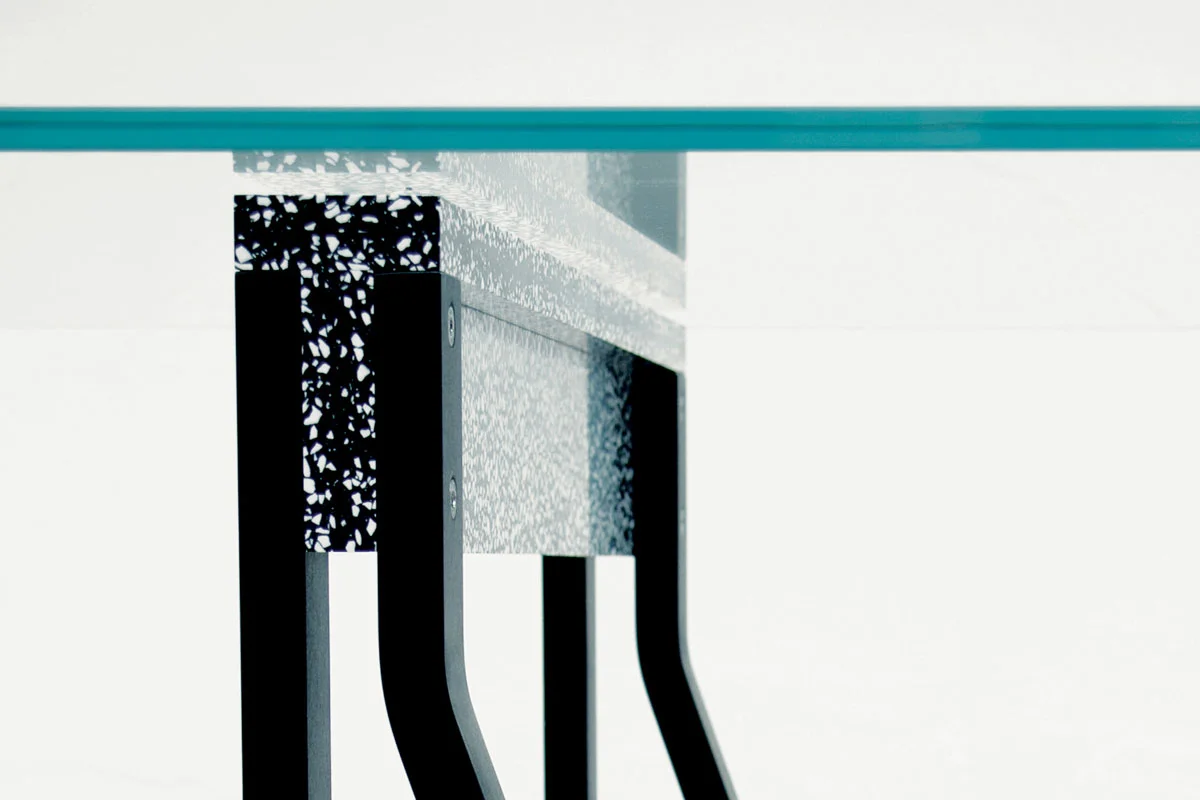

“White Chip Tresles,” (2010). Corian and anondised aluminium and glass top. Courtesy the artist.

“Piega,” (2010). Folded inox. Courtesy the artist.

“Y lights,” (2012). Corian and LED lights. Courtesy the artist.

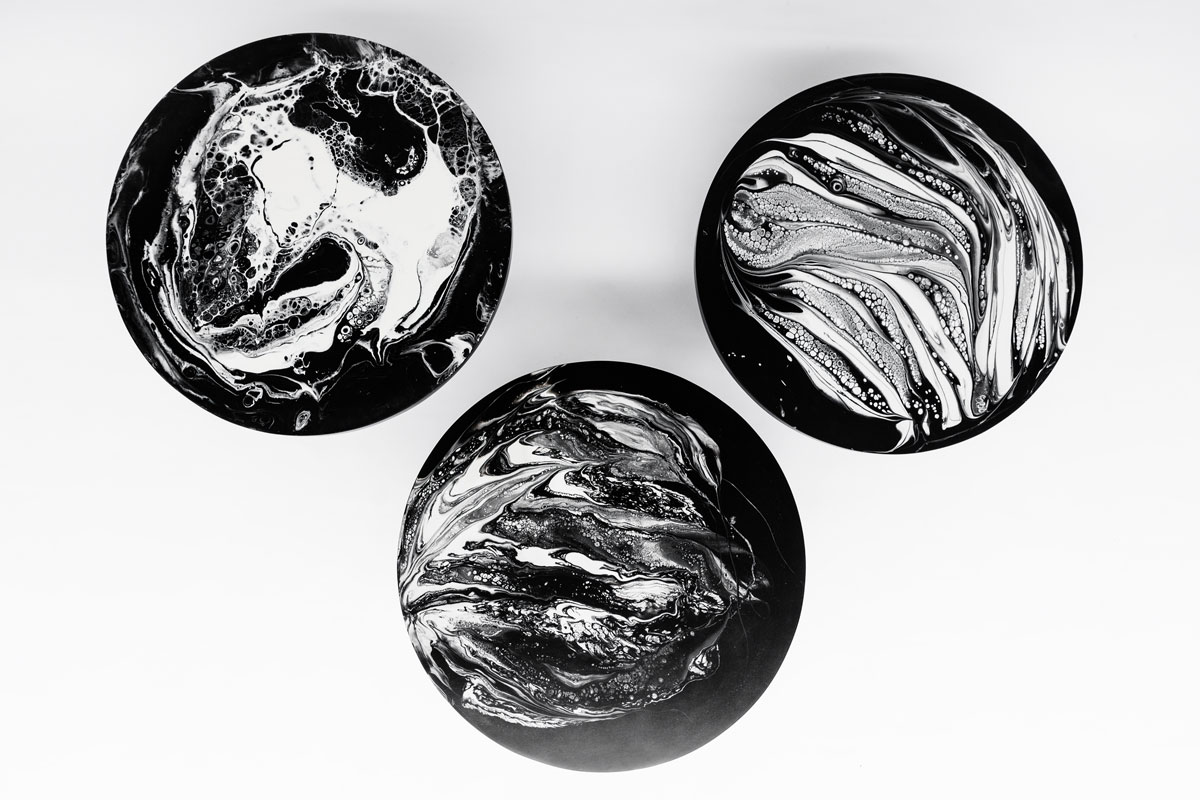

“Biological Marble tables,” (2013). Resin top and painted metal. Courtesy the artist.

[](#)[](#)

Victoria Wilmotte

Alternative Creature Comforts: Epoxy and Lime.

The word “machine” conjures up some pretty specific images, and a statement such as “having an idea and pushing the machine to do it” sounds awesomely Orwellian and Borg-like, especially coming from the mouth of a 27-year-old Frenchwoman with a blond pageboy haircut. The confusion is comically and completely my fault—or rather, the fault of the way we Americans (ab)use the English language. Our narrow and specific understanding of words like “machine” or “factory” or “technique” obfuscates what they actually mean: a machine is simply a tool; a factory is any place things get made; a technique is nothing more than the way one does something.

And it’s this distillation of language that provides a good juxtaposition to what Victoria Wilmotte is trying to accomplish in her design. “Successful furniture is not only functional, it’s more of a gesture,” she explains. “It’s more to create a picture. I don’t want a table to be a polyform table with no design; I think design can be between the structural and the functional.” She takes basic everyday furniture—tables, chairs, wall mirrors—and breaks them down to their most basic elements. A table supports, a mirror reflects. Her Pila Bench is a massive slab of lacquered wood set atop two pillars of brushed stainless steel. A marble stool is just a circle on four thin pieces of laminated steel, with a handle ingeniously spanning the seat.

In some ways the simplicity can be subversively literal: her White Chip Table resembles a kitchen countertop because it is made of Corian, a trademarked material created by Dupont for the purpose of (surprise!) making kitchen countertops. Some of her tables (she likes tables) are fat slices of limestone or glass balanced on delicate, spindly legs that look like Giacometti sculptures. And it’s with this heaviness and fragility that Wilmotte attempts to balance form and function.

She explains her use of heavy materials by saying they “are maybe difficult to transport, or move into your house, but in a way they look more stable and un-damageable.” She also doesn’t care that she is a woman who is making rather indelicate or archetypally unfeminine things: “If we believe that femininity in design is making things in pink and with flower patterns, we can say my work is a bit masculine, but we can also see and feel femininity in my design another way: Maybe the way I connect colors and materials together?”

Or maybe it’s just not important to her at all—she’s had to deal with her share of cynics and killjoys because her father founded a hugely successful architecture firm. When I mention that it would seem natural for her to collaborate with her father on a project, she gets the slightest edge in her voice. “No, I’m trying to define my own style and my own personality. Because in France it’s very often you hear ‘Oh, she’s the daughter of so-and-so. Is she okay? Or is she doing well because of…’” She trails off. “You know.”

For Wilmotte, maintaining the very slight line between art and design is an ongoing challenge. She talks about a chair designed by German designer Konstantin Grcic: “He made it with a concrete base, you know? It’s very hard. You can \[hurt\] your back. But, I don’t know. At least I can sit down. It’s not comfortable, but I like the weirdness of the object.” And while Wilmotte is looking to challenge traditional ideas of what commonplace objects can be, she is not looking to veer into $15,000-balloon-dog territory. “I don’t want to force it. Not like Jeff Koons; he makes those little copies which are impossible to make unless you have the mold, too...I think about making affordable objects, you know? It’s about trying to make sculptural objects but keeping the industrial way of making them.”

Wilmotte’s goals, then, as a young, successful designer, are simple enough: make interesting things; then, have them be useful; then, if possible, have them be practical and affordable enough so that people actually can buy them. Is there a middle ground between Jeff Koons and Ikea?