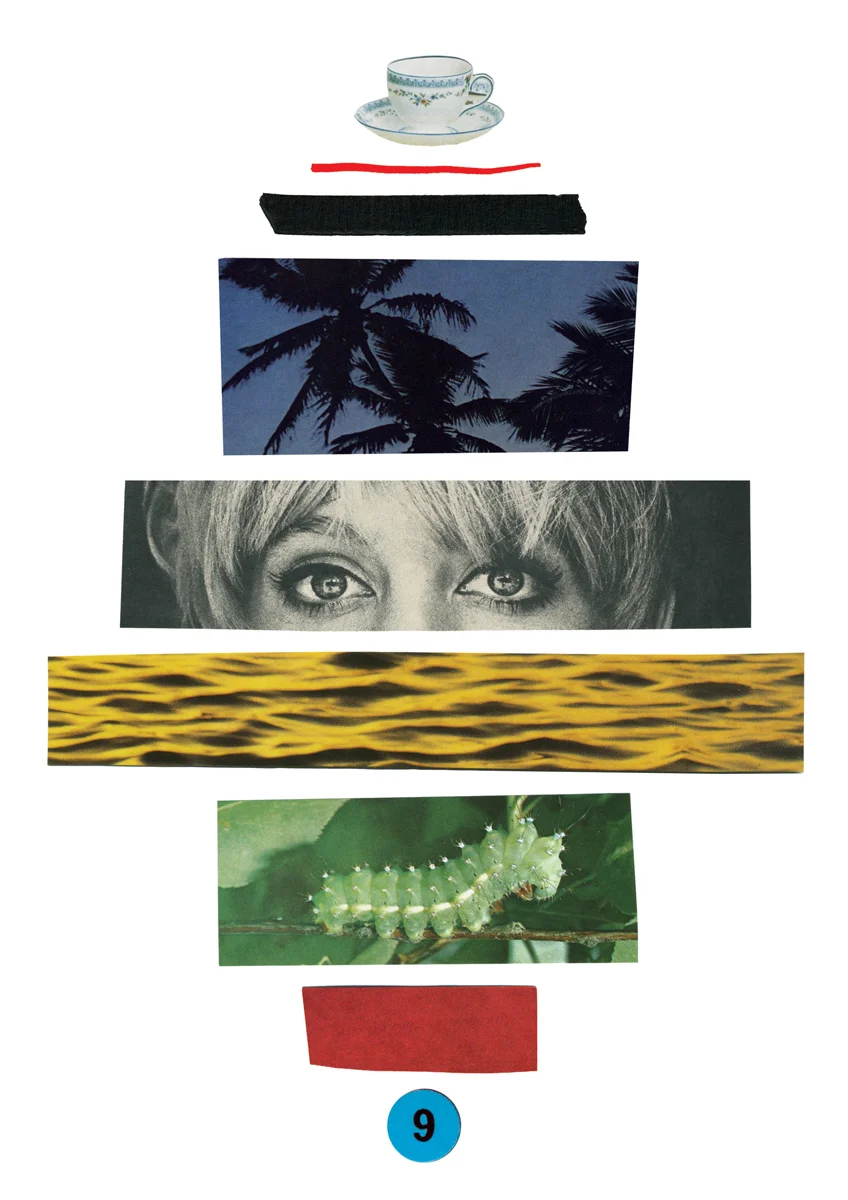

Anthony Zinonos. “nineLIVES,” (2014). Collage and paper on pencil. 25 x 35 centimeters. Courtesy the artist.

[](#)[](#)

Nine Lives

Metempsychosis, or the Search of Lost Time

I. She said becoming human was like watching rain from a distance, like a tree root that bursts open a sewer pipe, decades of rebar and benzene, copper and stone. When the lines in the dirt parted each of her eyelids, the heaviest parts fell away from pressure, each wet hot blink a new trench separated along a rigid fault. The first time she met God, He did not even introduce Himself. “How brazen you are,” she told Him. “How lucky for you the stamens do what you say.”

II. It was God who decided in her next life she should be a lightning bug. Her mother said to her, if you’re light, then you’ll know it. You don’t have to say you are

a sundog. You don’t need to write it on the back of your hand. You’ll know it the way you know you are near an ocean, the way one feels the waves of it in the space between where their feet hang before they step, the way bus drivers shield their eyes when they look in your direction, the way bus drivers give up and leave their busses in the street.

III. In her third life she was the part of the sky that gets turned into darkness, and each night she crawled down out of the moonlight so sure of herself she couldn’t keep from helping the plants plot their trajectories. She couldn’t stop herself from climbing into maple trees to talk to the birds about how their flying was coming along.

IV. When God saw this, He was so jealous He swore up and down that He’d make her a caterpillar. Then when she was a caterpillar, she fed herself to a yellow jacket that dive-bombed a president. “Fuck you,” the president said to the yellow jacket.

“Fuck you,” the caterpillar said again and again.

V. The next time God sent her back to earth, he told her she could just go be whatever, and naturally she chose water. It was in this way she lived for centuries as ice, as a storm cloud, as a left foot, as a rose petal, as a dung beetle, as an orangutan. She was a hot tub on a Norwegian Sun cruise ship. She hopped a ride in a swimsuit, rode the plumbing lines of a washing machine, infiltrated the drinking water, swirled around in a toilet bowl before finally drying up during a drought on a soybean farm in the Midwest.

VI. When she got back to Heaven she took a break for a while and served a stint at the end of the light tunnel, where, depending on the day, she only whispered, “Come to the light,” or “It’s not your time; you have to go back.” She switched shifts with a friend to be the intermediary to a psychic whose television show was in the process of getting canceled. Then she spent several years at a water feature in an Iowa mall carrying the good wishes back to be filed by date.

VII. When it was time to return to earth again, God brought her a handwritten list of options. She was tired by then, without the gumption that had sustained her for so long. “Just try something,” God urged her. “If you don’t like it, you can jump in front of a tractor trailer.”

“I was so good as the night sky,” she remembered.

“I know,” God said, apologetically. “I know.”

VIII. Next she chose a teacup because it seemed so easy, restful. She enjoyed the way the potter hugged her into existence, the way shoppers admired her on the shelf in the specialty boutique, the feel of that first pour of hot water filling her insides. She liked the dark of the cupboard; even the soft dust of the thrift store. She didn’t mind being donated to the woman who was restarting her life in the apartment by the African grocery. She even enjoyed the way the air split around her when she was chucked against a wall during a particularly heated argument, when she laid against the kitchen tile in pieces, satisfied and awake.

IX. Afterwards she became an orange peel, then a camping lantern, before finally she took a gig as a robin and was born in the highest branches of a walnut tree. One night the night sky descended from its orbit to hold her. “How’s the flying coming along?” it asked her, and she smiled in a way she didn’t know she could smile. “I think you’re doing great,” it told her. “I think the whole flying thing was meant for you.”

Anthony Zinonos. “nineLIVES,” (2014). Collage and paper on pencil. 25 x 35 centimeters. Courtesy the artist.