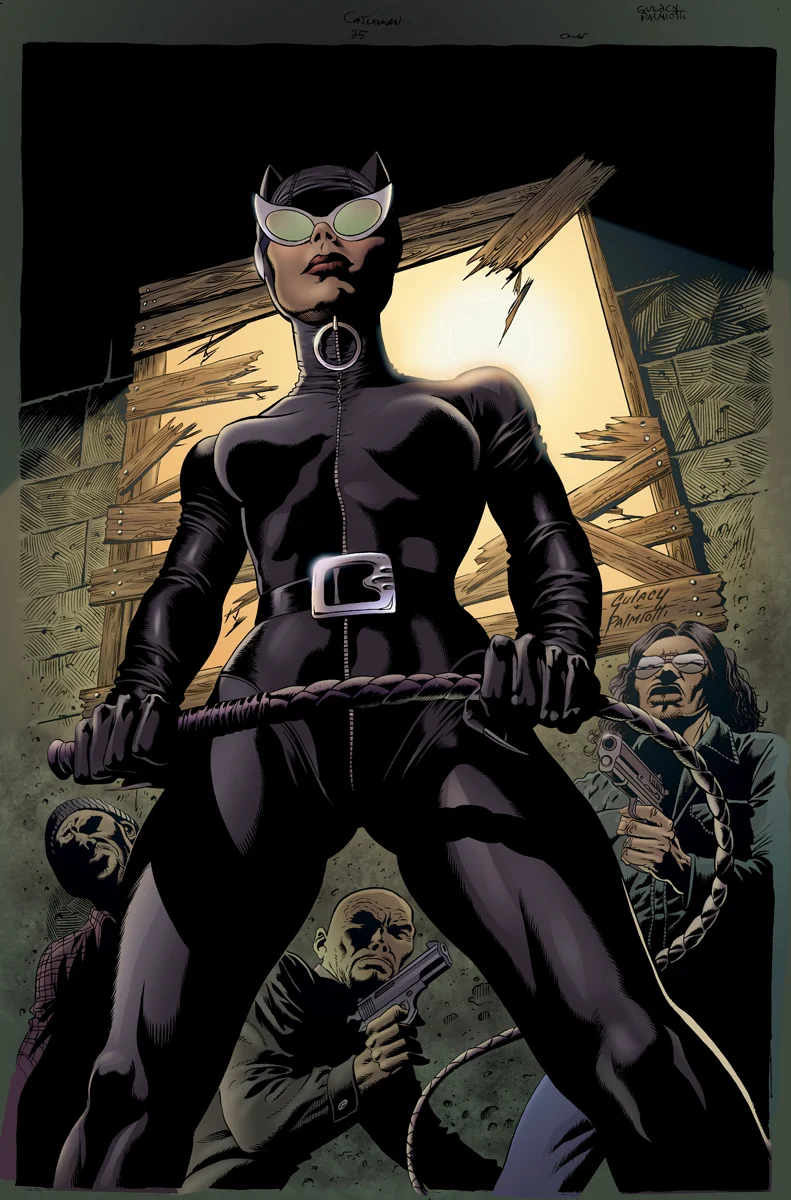

Paul Gulacy and Jimmy Palmiotti. “CATWOMAN #25,” (2013). Ink on print. 10 x 6.6 inches. Courtesy DC Comics, Burbank.

Michael Allred. “Untitled Pinup,” (2003) Ink on print. 10 x 6.6 inches. From _Selina’s Big Score_. Courtesy Titan Books Ltd, London and DC Comics, Burbank.

Michelle Pfeiffer as Catwoman.

_Batman Returns_, (1992). 126 minutes. 35mm. Courtesy Warner Bros. Entertainment.

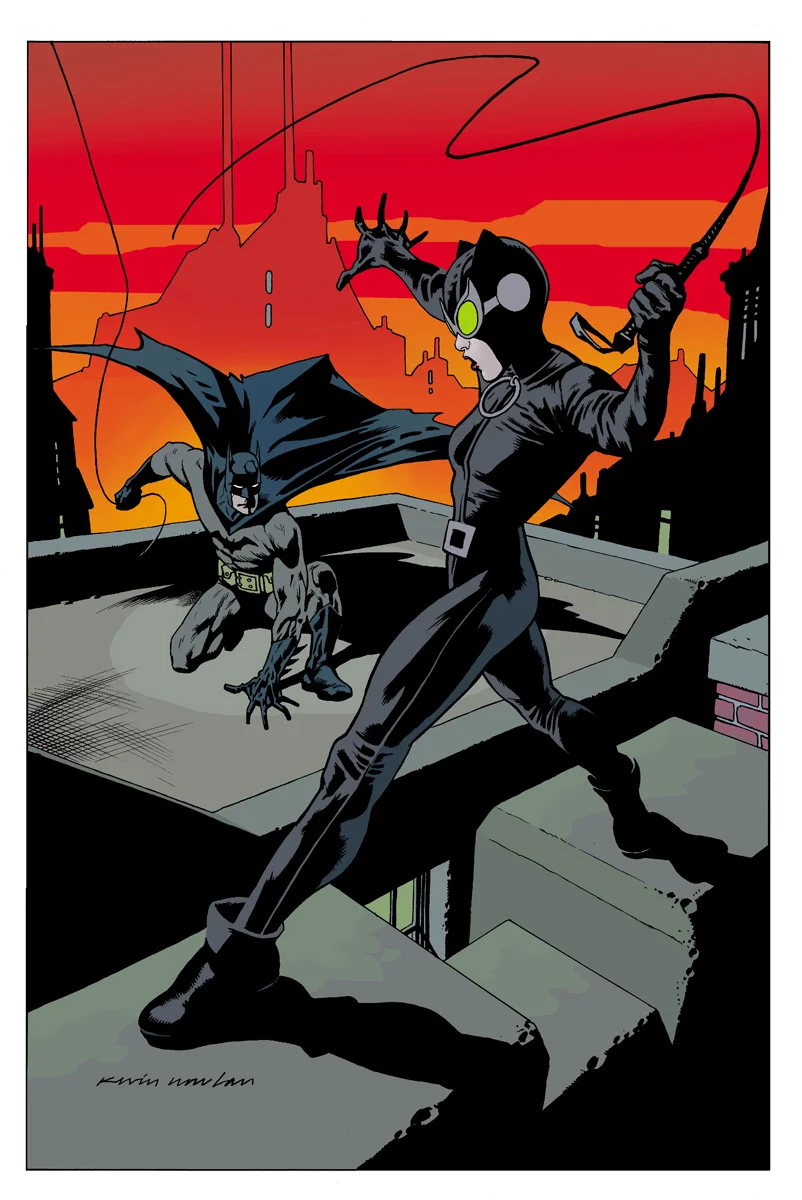

Kevin Nowlan. “Untitled Pinup,” (2003). Ink on print. 10 x 6.6 inches. From _Selina’s Big Score_. Courtesy Titan Books Ltd, London and DC Comics, Burbank.

Guillem March. “CATWOMAN #4,” (2011). Ink on print. 10 x 6.6 inches. Courtesy DC

Comics, Burbank.

[](#)[](#)

Catwoman

To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar Landing on Her Feet

Julie Newmar first stepped on set in 1966, clad in a skintight black suit, belt slung low around her hips, cat eared and cat eyed, all purrs and smolder, Selina Kyle, the Catwoman, was already 26 years old. But Newmar brought the sex and titillation to the television, catapulting Catwoman into the public’s collective consciousness, away from the McCarthyist ghetto of post-war comic books.

Catwoman first emerged in 1940 in the pages of Batman No. 1, as “The Cat,” a relatively undefined, prefigured _femme fatale_. But her character was quickly shaped, some elements emerging in that very issue—young and beautiful, lover of jewels, clawed, threatening. At 74 years old, Catwoman has survived many iterations and interpretations—jewel thief, aristocrat, corporate vice president, prostitute, pet store owner, mother, presumed-dead. She is Robin Hood and villainess, battered wife and dominatrix, Julie Newmar and Lee Meriwether and Eartha Kitt and Michelle Pfeiffer and Halle Berry and Anne Hathaway, ever skirting the line between sex icon and sex object, nimble on her feet.

_Birth on the Brink of War_ In the mad dash that birthed the superhero comic book genre, writers and artists were quick to recycle old tropes and adapt existing forms—gangster, crime, noir, sex—in order to bolster their four-color dreams. Superman, Batman, and the rest emerged not as men clad in underwear or spandex, but as circus strongmen in trunks, metaphors writ large by poor Jewish boys to combat the menacing concept of Friedrich Nietzsche’s superhuman _Übermensch_, under the employ of German fascism. Buried within these characters were immigrant dreams, anxieties of war and impotence, reclamations and declarations of masculinity.

Bob Kane and Bill Finger, the same boys who dreamed Batman into existence, conjured up Catwoman as the embodiment of all their pubescent dreams—astounding beauty, sexual prowess, intimidation. She was the girl all the boys feared, a knife in the side of American masculinity, twisting with the supposed insult of women in wartime industry—the girl the boys thought they should dominate before she dominates them, blooming desire and discomfort in the space between the gut and the groin.

Though graced with feline flexibility, Catwoman isn’t beyond the trappings of the genre. Her femininity appears in relation and in opposition to masculinity. That is to say, her sexuality, her agency: none of it exists in a vacuum. Catwoman is intertwined with Batman and caught in a cat-and-mouse love game. She’s his greatest failed chance at love and healing, underscoring Batman’s dedication to the mission above all else; or a proto-feminist unconcerned with Batman’s arrested boyhood; or a straw-feminist cuckold in leather with a whip.

_Threat, Sex, & Power_ With the rise of the Comics Code Authority, the industry’s reactionary censoring board and de facto McCarthyist gag, Catwoman vanished from 1954 to 1966, despite demonstrated artistic and economic success. Hushed away for fear of violating the CCA’s rules, Catwoman’s feminine wiles were deemed a threat in the post-war period. That fearful text of sexual women was buried, rendered safer as a buttoning up, a subtextual boner. Perhaps a blessing in disguise, the ’54 print death of Catwoman made Selina Kyle’s triumphant, dazzling, arched-brow return in the 1966 _Batman_ television series all the more so.

Marked by over-the-top campiness, the _Batman_ television series gave platform to the dancing and purring of Julie Newmar, Eartha Kitt, and Lee Meriwether in the ’66 film of the same name. The narrative and moral simplicities of the series provided an escape from the uncertainties of war and civil unrest. “Vietnam came and things got darker and darker and darker,” Newmar reflected in 2012, and the show stood in juxtapose, with Batphones, the Batusi, and Romero’s painted-over mustache.

Despite the campy tone and gee-whiz morals, not even _Batman_ could escape the turbulence of the 1960s—Eartha Kitt wouldn’t allow it. Born to black and white parentage in South Carolina, Kitt navigated entertainment within that liminal space, playing to and swinging between Newmar’s vanilla whiteness and perceived black animus. Tacitly barred from showing sexual tension between Batman and Catwoman for fear of evoking miscegenation anxieties, Kitt instead played Catwoman as a villain proper—and there is no reading around the idea that a black Catwoman in 1968 was more dangerous than a white one. The danger of race (and solidarity) _was_ more real—Kitt herself was an outspoken activist, critical of the Vietnam War, which garnered public scrutiny and CIA surveillance. Though Newmar stands iconic, Eartha Kitt, the self-proclaimed “sex kitten,” offered a Catwoman with unapologetic sexiness and true, dangerous magnetism.

_Nine Lives & Second Acts_ A medium defined by a thousand artists, each with their own visions and mandates, the comic book is a form constantly explaining itself, pining for cultural legitimacy and a bigger market share. With the rise of the superhero movie to summer blockbuster tentpole, that share is growing. In _The Dark Knight Rises,_ the final chapter of Christopher Nolan’s trilogy, Anne Hathaway’s turn as Selina gave viewers a razor-witted master thief and proletarian heroine. Despite Hathaway’s success and the proven strength of the character, it seems unlikely that Catwoman will get her own standalone—film studios seem frightened, too willing to let white, male heroes break ground first before introducing women as afterthoughts, like Scarlett Johansson’s Black Widow or Gal Gadot’s upcoming Wonder Woman. Missed opportunities, it seems, hedging bets on the stalwart white, male, heterosexual, 18-34 demographic—lest we forget, Hathaway reminds, “I’m adaptable.”

Jonathan Hickman, noted Marvel and indie writer, argues that comic books are “perpetually stuck in the second act,” with pastiche origin in place, ever in conflict, rise, or retelling. It is fertile ground for meditation, _a la_ Anne Hathaway’s occupied dreams and nightmares of revolution; burial, as in Halle Berry’s all sex, no-plot flop; and endless rebirth. Purple dress, leather jumpsuit, cat ears, tactical goggles, villain, antihero, hero, sex, or sexual liberation—each issue, film, television series, and video game is a new life. Her gravity is undeniable and we can’t help but be fascinated. Yesterday a seductress, today a crime boss, tomorrow unpredictable; 74 and counting; at least 9 lives, likely more.