[**LOUIS VUITTON**](https://us.louisvuitton.com/eng-us/homepage) tracksuit.

“The modern loss of faith does not concern just god or the hereafter,” writes Byung-Chul Han, the Korean- German phenomenologist. “It involves reality itself and makes human life radically fleeting.” Heady stuff, but such reflection comes naturally for 35-year-old actor Steven Yeun, whose roles often confront the darkest corners of human nature. Han is just one of the many figures who populate Yeun’s bookshelves, and Yeun revisits him often to deepen his understanding of life, reality, and art.

I meet Yeun at Maru Coffee in Los Feliz to discuss his new film, _Burning_. He arrives dressed as his character, Ben, might have—black sweater, slim jeans, and black loafers, casualness belying celebrity.While Ben might or might not be a serial killer, Yeun is warm and funny, possessed of a disarming authenticity. Our conversation ranges from nostalgia for our Midwestern childhoods to the intersection of filmcraft and philosophies of life.

_Burning_, from writer/director Lee Chang-dong (_Poetry_, _Secret Sunshine_) is a master class in ambiguity. Based on Haruki Murakami’s short story “Barn Burning,” the film follows Jong-su (Yoo Ah-in), a poor aspiring novelist whose lonely life is kindled by the amorous attentions of Hae-mi (Jong- seo Jun), a spirited woman who loves pantomime and yearns to satisfy her “great hunger”—an existential desire to know the meaning resonant in all things. When Hae-mi leaves for Kenya in search of that understanding and returns to Korea accompanied by a new lover, the wealthy and mysterious Ben (Steven Yeun), Jong-su resigns passively to his demotion to third-wheel.

In one of the film’s most elegant sequences, the three spend an evening smoking pot at Jong-su’s farmhouse. Hae-mi undresses and dances hypnotically as the sun sinks below the horizon. Later, Ben confesses to Jong-su that he has a passion for setting fire to greenhouses. The next greenhouse he plans to burn, says Ben, is very close to Jong-su.

Shortly thereafter, Hae-mi goes missing, and Jong-su suspects Ben’s burning of greenhouses to be a metaphor for serial murder. He takes to stalking Ben, intent on learning the truth. The plot unfolds and Jong-su grows reckless. The truth recedes into ambiguity.

_Burning_ is not slow but _patient_, precise. Many scenes contain loaded silences, as if we’re always on the verge of revelation. Lee Chang-dong’s filmcraft is a refreshing contrast to much of American cinema. Does Yeun see anything distinctively Korean in the patience of Lee’s method? “Patience isn’t the virtue of Korea _per se_,” says Yeun. The barista drops off our tea in unadorned clay mugs, and he thanks her, smiling broadly. “I would actually argue against that. Korea is _fast_. You see this when you look at mainstream films that America rarely gets, rather than the art house stuff. The top tier always has auteurs, like Bong Joon-ho, Park Chan-wook, or Na Hong-jin. They have the luxury of patience.”

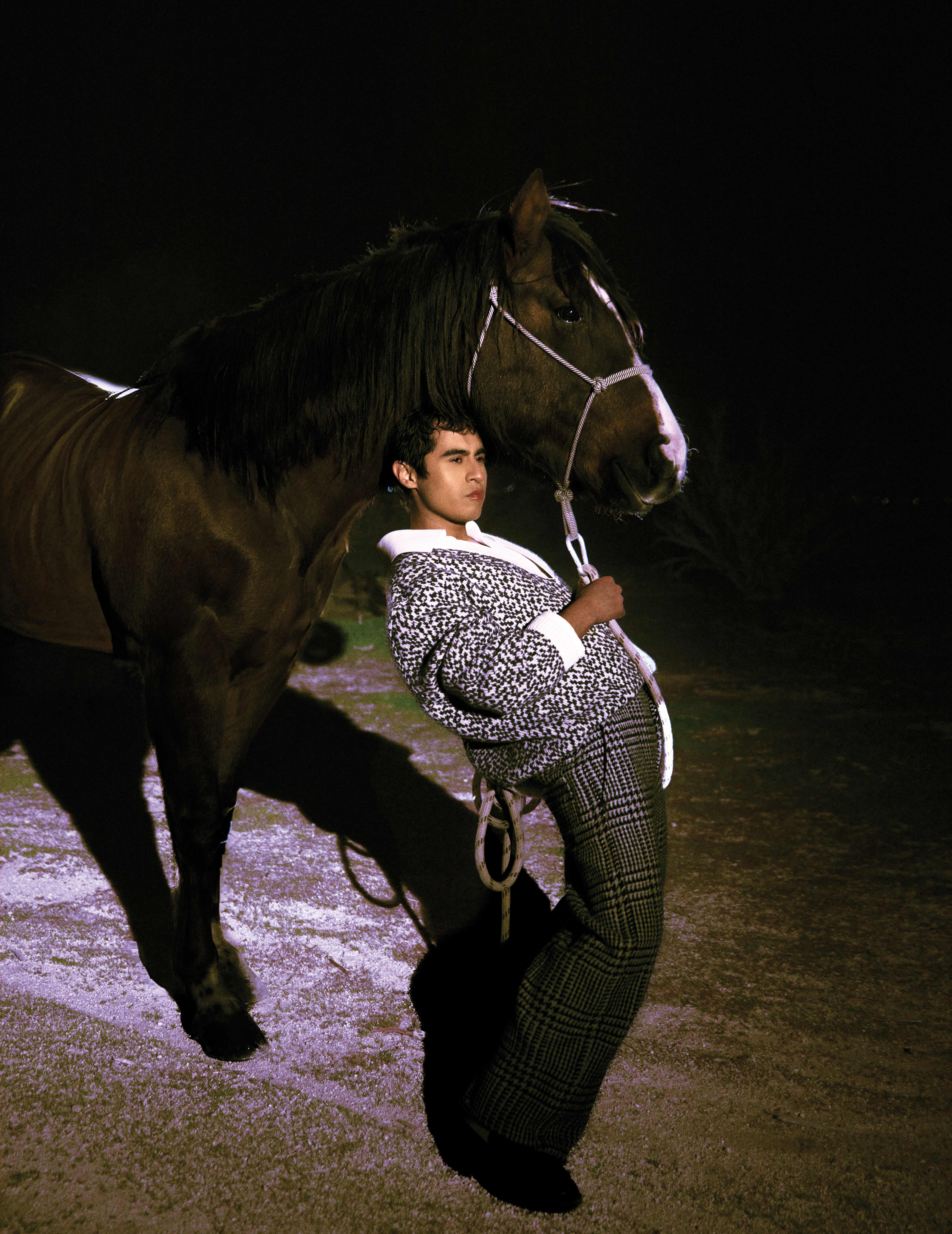

[**BOSS**](https://www.hugoboss.com/us/) coat, jacket, shirt, and pants.

He takes a sip and continues. “American filmmaking feels rushed. I don’t know if the auteurs of America have the same leeway as the auteurs of Korea. It’s still about budget and time. Whereas with _Burning_, we’re like, “Five months for shooting? Okay.” Who can do that here? Nowadays it’s a month, or two months. And two months is _crazy_.”

In _Burning_, the luxury of patience affords a reliance on natural light and climate, which facilitates the narrative’s seamless unfolding. Tension crystallizes and Jong-su’s resolve hardens in pace with the approach of winter. Scenes shot at dusk and gloaming complement the themes of liminality, transition, and dreamlike uncertainty.

“This was a magical situation where a lot of things came together that normally don’t get to,” says Yeun. He reiterates the “magical” quality of the shoot throughout our conversation. “the Director Lee, Yoo Ah-in, Jeon Jong-Seo, and myself would talk about it all the time, how natural the experience of the film felt. Just things that would happen, or moments that would arise out of the ashes of another ruined moment—that happened so many times. I don’t want to get overly serious about a film, but I do want to emphasize how very organic the experience of this film was, all overseen by the deft touch of a master filmmaker who has seen the world through a unique lens his whole life. Director Lee is one of those wonderful people who have seen a lot of crazy things and yet press on bravely to chart their own course. He’s a student of life. I admire that so much. Ah-in and I would talk a lot about how much he impressed us. He’s truly one of the greats.”

In art, the universal is accessed through the particular, the concrete. And _Burning_is nothing if not particular. American audiences will be struck by Jong-su’s deference to everyone he encounters, especially Ben. As idiom and manners are so revelatory, I ask what features of Korean culture are likely to be missed by non-Korean audiences.

“Korean society has a hierarchy built in,” says Yeun. “Interaction is based on your place in any given situation. So if I were meeting you for the first time, I’d ask your age, which will let me know if I should address you honorifically.

“Jong-su is indicative of a common Korean way of being, which is deferential. He constantly assesses his worth, making sure he’s playing the required role. Whereas Ben—the freaky part is that he’s not weighed down by any of these societal rules. When he acquiesces, it’s completely on his terms. I think that makes the power struggle between Ben and Jong-su more intense.”

[**ERMENEGILDO ZEGNA COUTURE**](https://www.zegna.us/us-en/home.html) suit, [**BASSIKE**](https://us.bassike.com) shirt, [**PIERRE HARDY**](https://www.pierrehardy.com/us_en/) shoes, and [**LU CHUNG**](https://lu-chung.com) socks.

Ben’s aloofness is palpable in ways that transcend cultural and linguistic barriers. Rather than flout expectations with disdain, he does so with blessed indifference. He’s at once socially and morally aloof, and yet capable of real generosity. Is he a serial killer bereft of conscience? Or is he a decent guy who’s been spiritually hollowed out by affluence and now resorts to occasional arson to feel alive?

My suspicion was that such a character must be difficult to inhabit. How did Yeun think his way into that ambiguity? Did he run with one interpretation? Or did he walk that knife’s edge the whole time?

“I rolled that edge pretty often,” says Yeun. “I’d chooseone way, and I’d realize it doesn’t make sense to go that far, and then I’d choose the other, with the same result. The real difficulty, though, came not in embodying Ben, but in shaking the character after I was done. “Someone who’s unlocked in that way—not a slave to any system—that’s an immense power. You glide effortlessly through life. It made starkly real to me how much my anxiety is predicated on my own attitudes. So Ben felt very powerful. That was something I had to come back to reality from after I had finished.”

Yeun’s trouble letting go of the character wasn’t purely internal. During his Korean press tour, he chose to stay in character. “When I go back and look at the interviews I did,” he says, “I’m kind of a dick. And I feel bad. People seemed to react positively, but you never know who I might have pissed off because I didn’t play along.”

It’s an interesting specimen of life imitating art. “The whole film was crazy like that,” Yeun says, excited. “That was only one of a trillion things that happened that felt like this magical film was making itself regardless of whether we wanted to go with it or not.”

_Burning_succeeds marvelously as a Murakami adaptation. There’s this feeling that anything is possible, even the surreal. “It’s perception, right?” says Yeun. “Our perceptions drive our lives. You really can change yourself by turning the angle slightly to the left or right. But it’s difficult because we’re afraid of failing. That’s something that this film helped me unpack— accepting the chaos of reality and going with it, rather than suffering through it by struggling against it.”

Chaos in Yeun’s life takes many forms: uncertainty about the future; the internet; raising a child; maintaining a healthy marriage. “Life is pure chaos,” he says, and laughs.

“Sometimes you’re driving down a familiar road, zoning out, and it’s all fine and good, and then you realize in a flash that a car could T-bone you and destroy you any second. We’re programmed to live in this easy-to-manage way, it’s how we deal with the anxieties of the world. But then those sweeping feelings come through and you realize how precious life is.”

[**Z ZEGNA**](https://www.zegna.us/us-en/home.html) shirt.

At first blush, Maru Coffee is an unlikely setting for existential musings. The edges are too crisp, the decor too Spartan, the light too bright. But it may just possess what the waiter from Hemingway’s “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place” knew to be necessary for dwelling on nothingness and questions of meaning.

“That’s what’s fun about embracing the chaos—things become more meaningful. In every interaction, Ben is the most present person. He looks vacant, but only to our eyes. It’s a nihilistic optimism, someone who’s gotten to base zero, to accept that everything is meaningless, and to rebuild the world from that framework.”

Yeun has previously discussed how Lee Chang-dong hoped his “American-ness” would lend a certain dissonance to his performance. Interestingly, Yeun felt “at home” for the first time playing Ben, and yet was able to function as a kind of_other_ for his Korean audience.

“Ben’s otherness,” says Yeun, “is rooted in the tension between individualism and collectivism. Americans live very singularly. I remember growing up as a Korean kid in predominately white neighborhoods and talking to my friends, and someone saying, ‘If I don’t get a job when I turn eighteen, my mom’s going to kick me out of the house and won’t help with college.’ To a Korean kid that sounds _crazy_. We’re lucky because that’s where collectivism serves us: everyone’s grinding for everyone else.

“But that kid getting kicked out is also beautiful because it respects the individual. Few Koreans get to experience that. You’re usually serving the whole and have to play your required part. But in the U.S. there’s this feeling that you can inhabit your own space. I feel much more like an individual here than I do in Korea.

Yeun sees the West as hungry for meaning and community, while the East seeks an easing of strictures. “I’ve met many young Koreans and they feel primed to transgress cultural boundaries,” he says. “The internet has really allowed East and West to cross-pollinate. The West is trying to grasp collectivism, and I think that’s what the West needs. And people in Asia are grasping their individualism. It’s cool to see that happening.”

They often mean well—they’re trying to give solace to those who feel alone. But they can easily become traps, because if you stay in your safe space, you never deal with the trauma that caused you to seek it out in the first place. The goal is to be free and comfortable in your own skin, and only then submitting yourself to the collective, as a full being and not as a fragment.”

[**Z ZEGNA**](https://www.zegna.us/us-en/home.html) suit and shirt.

The hope is to find that golden balance between collectivism and individualism. “If we got to real balance, it’d be beautiful,” says Yeun. “But that’s almost utopic.” He worries that a tendency to swing towards extremes may be hardwired in the system.

But what’s impossible in life is sometimes realized in art. During filming, director Lee would often approach his cast and say, simply, “Balance.” Certainly, every scene does feel perfectly weighed and measured.

“The dude is like a Zen master,” says Yeun. “And that equanimity matters because he’s a 64-year old man telling a story about the youth, and not telling them who they are, but rather telling them, ‘I’m giving you the space to express who you are to me so that I can help _you_ craft the story.’”

Balance, as a theme, features prominently in Murakami’s short story. The unnamed character that _Burning_’s Ben is based on speaks of his arson as a force of nature. “They’re waiting to be burned. I’m simply obliging... Just like the rain. The rain falls. Streams swell. Things get swept along.” His destructive acts are central to the balance of his “simultaneity,” his sense of existing everywhere at once, unbounded by time. “Without such balance,” he says, “I don’t think we could go on living.” The translation of this theme into _Burning_is nothing if not elegant.

\*\*\*

One of the stranger moments in _Burning_ comes when Jong- su stalks Ben at the latter’s church. Whether Ben is a killer or a ritual womanizer, his presence there feels utterly dissonant. I ask Yeun, who grew up in a devoutly Christian home, what role faith plays in his life.

“Faith, for me, is an ever-changing road. I’m very thankful that I got to study religion; it gave me a lot of information, although I didn’t gain much wisdom. But as I’ve grown older, having fallen away from the Church, I find myself being drawn back to it under different pretenses. Not that I need it to tell me how to live, but I want to carefully consider what the Christian Bible is trying to say. Or even the Qur’an, or the Torah, or Buddhist scripture—they’re all talking about the inherent wisdom of doing what you are meant to do in this universe, and going with its flow, as opposed to warring against it. At the moment, I’ve been re-reading passages in the Bible, and I’m like, _Whoa_, that means something completely different to me now. I really understand the wisdom of this passage.”

\*\*\*

[**BOSS**](https://www.hugoboss.com/us/) suit and shirt and [**PIERRE HARDY**](https://www.pierrehardy.com) shoes.

In a late scene in _Burning_, Hae-mi performs a dance she learned in Kenya. The dance—which enacts two “hungers”—is adapted from Sir Laurens van der Post’s study of the Kalahari Bushmen. “There is the Great Hunger and the Little Hunger,” writes van der Post. “The Little Hunger wants food for the belly; but the Great Hunger, the greatest hunger of all, is the hunger for meaning... There is nothing wrong in searching for happiness. But meaning is of far more comfort to the soul.”

It’s a revelatory scene. Jong-su observes Hae-mi’s movements with affection; he longs for her, but also through her, as if she’s come to mediate his pursuit of meaning. Ben, however, observes her with an unreadable expression. We’re left questioning whether this man, who has never known physical hunger, has also never hungered for meaning.

Eager to lock up and get on with their evening, the baristas finally ask us to leave. We finish our conversation outside in an alleyway. It is dusk and the air is refreshingly cool. Yeun’s driver waits nearby, his black blazer unbuttoned to reveal a comically long ivory tie riding the curve of his belly.

The Great Hunger is sated in different ways for each of us. Steven Yeun tries to feed it by “flowing with the universe as it comes.”

“I acknowledge that I’m in a very privileged position to say something like that,” he says. “I’m not suffering on my daily so that it’d be hard to go with the flow. But it feels purposeful. My favorite verse is Romans 12:2, ‘Do not conform to the pattern of this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your mind, then you will be able to test God’s good and perfect will.’ In understanding that, I feel that I’m in the flow, that what I desire is equivalent to what the universe desires in my life, so then I’m just an agent of the universe, I’m a wave in the ocean. That’s where I’m trying to find my Zen—this constant, careful consideration of myself. Every time I’ve tried to push against the current, it never works out, and I’m always devastated by it. But every time I just let go to the process, it becomes this magical lesson or experience.”

* * *

Photographed and filmed by: Shane Mccauley.

Stylist: Nicolas Klam at The Visionaries Agency.

Groomer: Sheridan Ward using Oribe at Cloutier Remix.

Photography Assistant: Jake Harrison.

Styling Assistant: Kyle Huewe.

[

sold out

](/store/issue-164)

[Issue 164](/store/issue-164)

$15.95

Outside Cover:

Select Outside Cover CAYETANO FERRERJULIANNE MOOREGARRETT HEDLUNDCOLSON BAKER

CAYETANO FERRER JULIANNE MOORE GARRETT HEDLUND COLSON BAKER

Add To Cart

document.querySelector('.product-block .product-block').classList.add('is-first-product-block');

[**LOUIS VUITTON**](https://us.louisvuitton.com/eng-us/homepage) tracksuit.

“The modern loss of faith does not concern just god or the hereafter,” writes Byung-Chul Han, the Korean- German phenomenologist. “It involves reality itself and makes human life radically fleeting.” Heady stuff, but such reflection comes naturally for 35-year-old actor Steven Yeun, whose roles often confront the darkest corners of human nature. Han is just one of the many figures who populate Yeun’s bookshelves, and Yeun revisits him often to deepen his understanding of life, reality, and art.

I meet Yeun at Maru Coffee in Los Feliz to discuss his new film, _Burning_. He arrives dressed as his character, Ben, might have—black sweater, slim jeans, and black loafers, casualness belying celebrity.While Ben might or might not be a serial killer, Yeun is warm and funny, possessed of a disarming authenticity. Our conversation ranges from nostalgia for our Midwestern childhoods to the intersection of filmcraft and philosophies of life.

_Burning_, from writer/director Lee Chang-dong (_Poetry_, _Secret Sunshine_) is a master class in ambiguity. Based on Haruki Murakami’s short story “Barn Burning,” the film follows Jong-su (Yoo Ah-in), a poor aspiring novelist whose lonely life is kindled by the amorous attentions of Hae-mi (Jong- seo Jun), a spirited woman who loves pantomime and yearns to satisfy her “great hunger”—an existential desire to know the meaning resonant in all things. When Hae-mi leaves for Kenya in search of that understanding and returns to Korea accompanied by a new lover, the wealthy and mysterious Ben (Steven Yeun), Jong-su resigns passively to his demotion to third-wheel.

In one of the film’s most elegant sequences, the three spend an evening smoking pot at Jong-su’s farmhouse. Hae-mi undresses and dances hypnotically as the sun sinks below the horizon. Later, Ben confesses to Jong-su that he has a passion for setting fire to greenhouses. The next greenhouse he plans to burn, says Ben, is very close to Jong-su.

Shortly thereafter, Hae-mi goes missing, and Jong-su suspects Ben’s burning of greenhouses to be a metaphor for serial murder. He takes to stalking Ben, intent on learning the truth. The plot unfolds and Jong-su grows reckless. The truth recedes into ambiguity.

_Burning_ is not slow but _patient_, precise. Many scenes contain loaded silences, as if we’re always on the verge of revelation. Lee Chang-dong’s filmcraft is a refreshing contrast to much of American cinema. Does Yeun see anything distinctively Korean in the patience of Lee’s method? “Patience isn’t the virtue of Korea _per se_,” says Yeun. The barista drops off our tea in unadorned clay mugs, and he thanks her, smiling broadly. “I would actually argue against that. Korea is _fast_. You see this when you look at mainstream films that America rarely gets, rather than the art house stuff. The top tier always has auteurs, like Bong Joon-ho, Park Chan-wook, or Na Hong-jin. They have the luxury of patience.”

[**LOUIS VUITTON**](https://us.louisvuitton.com/eng-us/homepage) tracksuit.

“The modern loss of faith does not concern just god or the hereafter,” writes Byung-Chul Han, the Korean- German phenomenologist. “It involves reality itself and makes human life radically fleeting.” Heady stuff, but such reflection comes naturally for 35-year-old actor Steven Yeun, whose roles often confront the darkest corners of human nature. Han is just one of the many figures who populate Yeun’s bookshelves, and Yeun revisits him often to deepen his understanding of life, reality, and art.

I meet Yeun at Maru Coffee in Los Feliz to discuss his new film, _Burning_. He arrives dressed as his character, Ben, might have—black sweater, slim jeans, and black loafers, casualness belying celebrity.While Ben might or might not be a serial killer, Yeun is warm and funny, possessed of a disarming authenticity. Our conversation ranges from nostalgia for our Midwestern childhoods to the intersection of filmcraft and philosophies of life.

_Burning_, from writer/director Lee Chang-dong (_Poetry_, _Secret Sunshine_) is a master class in ambiguity. Based on Haruki Murakami’s short story “Barn Burning,” the film follows Jong-su (Yoo Ah-in), a poor aspiring novelist whose lonely life is kindled by the amorous attentions of Hae-mi (Jong- seo Jun), a spirited woman who loves pantomime and yearns to satisfy her “great hunger”—an existential desire to know the meaning resonant in all things. When Hae-mi leaves for Kenya in search of that understanding and returns to Korea accompanied by a new lover, the wealthy and mysterious Ben (Steven Yeun), Jong-su resigns passively to his demotion to third-wheel.

In one of the film’s most elegant sequences, the three spend an evening smoking pot at Jong-su’s farmhouse. Hae-mi undresses and dances hypnotically as the sun sinks below the horizon. Later, Ben confesses to Jong-su that he has a passion for setting fire to greenhouses. The next greenhouse he plans to burn, says Ben, is very close to Jong-su.

Shortly thereafter, Hae-mi goes missing, and Jong-su suspects Ben’s burning of greenhouses to be a metaphor for serial murder. He takes to stalking Ben, intent on learning the truth. The plot unfolds and Jong-su grows reckless. The truth recedes into ambiguity.

_Burning_ is not slow but _patient_, precise. Many scenes contain loaded silences, as if we’re always on the verge of revelation. Lee Chang-dong’s filmcraft is a refreshing contrast to much of American cinema. Does Yeun see anything distinctively Korean in the patience of Lee’s method? “Patience isn’t the virtue of Korea _per se_,” says Yeun. The barista drops off our tea in unadorned clay mugs, and he thanks her, smiling broadly. “I would actually argue against that. Korea is _fast_. You see this when you look at mainstream films that America rarely gets, rather than the art house stuff. The top tier always has auteurs, like Bong Joon-ho, Park Chan-wook, or Na Hong-jin. They have the luxury of patience.”

[**BOSS**](https://www.hugoboss.com/us/) coat, jacket, shirt, and pants.

He takes a sip and continues. “American filmmaking feels rushed. I don’t know if the auteurs of America have the same leeway as the auteurs of Korea. It’s still about budget and time. Whereas with _Burning_, we’re like, “Five months for shooting? Okay.” Who can do that here? Nowadays it’s a month, or two months. And two months is _crazy_.”

In _Burning_, the luxury of patience affords a reliance on natural light and climate, which facilitates the narrative’s seamless unfolding. Tension crystallizes and Jong-su’s resolve hardens in pace with the approach of winter. Scenes shot at dusk and gloaming complement the themes of liminality, transition, and dreamlike uncertainty.

“This was a magical situation where a lot of things came together that normally don’t get to,” says Yeun. He reiterates the “magical” quality of the shoot throughout our conversation. “the Director Lee, Yoo Ah-in, Jeon Jong-Seo, and myself would talk about it all the time, how natural the experience of the film felt. Just things that would happen, or moments that would arise out of the ashes of another ruined moment—that happened so many times. I don’t want to get overly serious about a film, but I do want to emphasize how very organic the experience of this film was, all overseen by the deft touch of a master filmmaker who has seen the world through a unique lens his whole life. Director Lee is one of those wonderful people who have seen a lot of crazy things and yet press on bravely to chart their own course. He’s a student of life. I admire that so much. Ah-in and I would talk a lot about how much he impressed us. He’s truly one of the greats.”

In art, the universal is accessed through the particular, the concrete. And _Burning_is nothing if not particular. American audiences will be struck by Jong-su’s deference to everyone he encounters, especially Ben. As idiom and manners are so revelatory, I ask what features of Korean culture are likely to be missed by non-Korean audiences.

“Korean society has a hierarchy built in,” says Yeun. “Interaction is based on your place in any given situation. So if I were meeting you for the first time, I’d ask your age, which will let me know if I should address you honorifically.

“Jong-su is indicative of a common Korean way of being, which is deferential. He constantly assesses his worth, making sure he’s playing the required role. Whereas Ben—the freaky part is that he’s not weighed down by any of these societal rules. When he acquiesces, it’s completely on his terms. I think that makes the power struggle between Ben and Jong-su more intense.”

[**BOSS**](https://www.hugoboss.com/us/) coat, jacket, shirt, and pants.

He takes a sip and continues. “American filmmaking feels rushed. I don’t know if the auteurs of America have the same leeway as the auteurs of Korea. It’s still about budget and time. Whereas with _Burning_, we’re like, “Five months for shooting? Okay.” Who can do that here? Nowadays it’s a month, or two months. And two months is _crazy_.”

In _Burning_, the luxury of patience affords a reliance on natural light and climate, which facilitates the narrative’s seamless unfolding. Tension crystallizes and Jong-su’s resolve hardens in pace with the approach of winter. Scenes shot at dusk and gloaming complement the themes of liminality, transition, and dreamlike uncertainty.

“This was a magical situation where a lot of things came together that normally don’t get to,” says Yeun. He reiterates the “magical” quality of the shoot throughout our conversation. “the Director Lee, Yoo Ah-in, Jeon Jong-Seo, and myself would talk about it all the time, how natural the experience of the film felt. Just things that would happen, or moments that would arise out of the ashes of another ruined moment—that happened so many times. I don’t want to get overly serious about a film, but I do want to emphasize how very organic the experience of this film was, all overseen by the deft touch of a master filmmaker who has seen the world through a unique lens his whole life. Director Lee is one of those wonderful people who have seen a lot of crazy things and yet press on bravely to chart their own course. He’s a student of life. I admire that so much. Ah-in and I would talk a lot about how much he impressed us. He’s truly one of the greats.”

In art, the universal is accessed through the particular, the concrete. And _Burning_is nothing if not particular. American audiences will be struck by Jong-su’s deference to everyone he encounters, especially Ben. As idiom and manners are so revelatory, I ask what features of Korean culture are likely to be missed by non-Korean audiences.

“Korean society has a hierarchy built in,” says Yeun. “Interaction is based on your place in any given situation. So if I were meeting you for the first time, I’d ask your age, which will let me know if I should address you honorifically.

“Jong-su is indicative of a common Korean way of being, which is deferential. He constantly assesses his worth, making sure he’s playing the required role. Whereas Ben—the freaky part is that he’s not weighed down by any of these societal rules. When he acquiesces, it’s completely on his terms. I think that makes the power struggle between Ben and Jong-su more intense.”

[**ERMENEGILDO ZEGNA COUTURE**](https://www.zegna.us/us-en/home.html) suit, [**BASSIKE**](https://us.bassike.com) shirt, [**PIERRE HARDY**](https://www.pierrehardy.com/us_en/) shoes, and [**LU CHUNG**](https://lu-chung.com) socks.

Ben’s aloofness is palpable in ways that transcend cultural and linguistic barriers. Rather than flout expectations with disdain, he does so with blessed indifference. He’s at once socially and morally aloof, and yet capable of real generosity. Is he a serial killer bereft of conscience? Or is he a decent guy who’s been spiritually hollowed out by affluence and now resorts to occasional arson to feel alive?

My suspicion was that such a character must be difficult to inhabit. How did Yeun think his way into that ambiguity? Did he run with one interpretation? Or did he walk that knife’s edge the whole time?

“I rolled that edge pretty often,” says Yeun. “I’d chooseone way, and I’d realize it doesn’t make sense to go that far, and then I’d choose the other, with the same result. The real difficulty, though, came not in embodying Ben, but in shaking the character after I was done. “Someone who’s unlocked in that way—not a slave to any system—that’s an immense power. You glide effortlessly through life. It made starkly real to me how much my anxiety is predicated on my own attitudes. So Ben felt very powerful. That was something I had to come back to reality from after I had finished.”

Yeun’s trouble letting go of the character wasn’t purely internal. During his Korean press tour, he chose to stay in character. “When I go back and look at the interviews I did,” he says, “I’m kind of a dick. And I feel bad. People seemed to react positively, but you never know who I might have pissed off because I didn’t play along.”

It’s an interesting specimen of life imitating art. “The whole film was crazy like that,” Yeun says, excited. “That was only one of a trillion things that happened that felt like this magical film was making itself regardless of whether we wanted to go with it or not.”

_Burning_succeeds marvelously as a Murakami adaptation. There’s this feeling that anything is possible, even the surreal. “It’s perception, right?” says Yeun. “Our perceptions drive our lives. You really can change yourself by turning the angle slightly to the left or right. But it’s difficult because we’re afraid of failing. That’s something that this film helped me unpack— accepting the chaos of reality and going with it, rather than suffering through it by struggling against it.”

Chaos in Yeun’s life takes many forms: uncertainty about the future; the internet; raising a child; maintaining a healthy marriage. “Life is pure chaos,” he says, and laughs.

“Sometimes you’re driving down a familiar road, zoning out, and it’s all fine and good, and then you realize in a flash that a car could T-bone you and destroy you any second. We’re programmed to live in this easy-to-manage way, it’s how we deal with the anxieties of the world. But then those sweeping feelings come through and you realize how precious life is.”

[**ERMENEGILDO ZEGNA COUTURE**](https://www.zegna.us/us-en/home.html) suit, [**BASSIKE**](https://us.bassike.com) shirt, [**PIERRE HARDY**](https://www.pierrehardy.com/us_en/) shoes, and [**LU CHUNG**](https://lu-chung.com) socks.

Ben’s aloofness is palpable in ways that transcend cultural and linguistic barriers. Rather than flout expectations with disdain, he does so with blessed indifference. He’s at once socially and morally aloof, and yet capable of real generosity. Is he a serial killer bereft of conscience? Or is he a decent guy who’s been spiritually hollowed out by affluence and now resorts to occasional arson to feel alive?

My suspicion was that such a character must be difficult to inhabit. How did Yeun think his way into that ambiguity? Did he run with one interpretation? Or did he walk that knife’s edge the whole time?

“I rolled that edge pretty often,” says Yeun. “I’d chooseone way, and I’d realize it doesn’t make sense to go that far, and then I’d choose the other, with the same result. The real difficulty, though, came not in embodying Ben, but in shaking the character after I was done. “Someone who’s unlocked in that way—not a slave to any system—that’s an immense power. You glide effortlessly through life. It made starkly real to me how much my anxiety is predicated on my own attitudes. So Ben felt very powerful. That was something I had to come back to reality from after I had finished.”

Yeun’s trouble letting go of the character wasn’t purely internal. During his Korean press tour, he chose to stay in character. “When I go back and look at the interviews I did,” he says, “I’m kind of a dick. And I feel bad. People seemed to react positively, but you never know who I might have pissed off because I didn’t play along.”

It’s an interesting specimen of life imitating art. “The whole film was crazy like that,” Yeun says, excited. “That was only one of a trillion things that happened that felt like this magical film was making itself regardless of whether we wanted to go with it or not.”

_Burning_succeeds marvelously as a Murakami adaptation. There’s this feeling that anything is possible, even the surreal. “It’s perception, right?” says Yeun. “Our perceptions drive our lives. You really can change yourself by turning the angle slightly to the left or right. But it’s difficult because we’re afraid of failing. That’s something that this film helped me unpack— accepting the chaos of reality and going with it, rather than suffering through it by struggling against it.”

Chaos in Yeun’s life takes many forms: uncertainty about the future; the internet; raising a child; maintaining a healthy marriage. “Life is pure chaos,” he says, and laughs.

“Sometimes you’re driving down a familiar road, zoning out, and it’s all fine and good, and then you realize in a flash that a car could T-bone you and destroy you any second. We’re programmed to live in this easy-to-manage way, it’s how we deal with the anxieties of the world. But then those sweeping feelings come through and you realize how precious life is.”

[**Z ZEGNA**](https://www.zegna.us/us-en/home.html) shirt.

At first blush, Maru Coffee is an unlikely setting for existential musings. The edges are too crisp, the decor too Spartan, the light too bright. But it may just possess what the waiter from Hemingway’s “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place” knew to be necessary for dwelling on nothingness and questions of meaning.

“That’s what’s fun about embracing the chaos—things become more meaningful. In every interaction, Ben is the most present person. He looks vacant, but only to our eyes. It’s a nihilistic optimism, someone who’s gotten to base zero, to accept that everything is meaningless, and to rebuild the world from that framework.”

Yeun has previously discussed how Lee Chang-dong hoped his “American-ness” would lend a certain dissonance to his performance. Interestingly, Yeun felt “at home” for the first time playing Ben, and yet was able to function as a kind of_other_ for his Korean audience.

“Ben’s otherness,” says Yeun, “is rooted in the tension between individualism and collectivism. Americans live very singularly. I remember growing up as a Korean kid in predominately white neighborhoods and talking to my friends, and someone saying, ‘If I don’t get a job when I turn eighteen, my mom’s going to kick me out of the house and won’t help with college.’ To a Korean kid that sounds _crazy_. We’re lucky because that’s where collectivism serves us: everyone’s grinding for everyone else.

“But that kid getting kicked out is also beautiful because it respects the individual. Few Koreans get to experience that. You’re usually serving the whole and have to play your required part. But in the U.S. there’s this feeling that you can inhabit your own space. I feel much more like an individual here than I do in Korea.

Yeun sees the West as hungry for meaning and community, while the East seeks an easing of strictures. “I’ve met many young Koreans and they feel primed to transgress cultural boundaries,” he says. “The internet has really allowed East and West to cross-pollinate. The West is trying to grasp collectivism, and I think that’s what the West needs. And people in Asia are grasping their individualism. It’s cool to see that happening.”

They often mean well—they’re trying to give solace to those who feel alone. But they can easily become traps, because if you stay in your safe space, you never deal with the trauma that caused you to seek it out in the first place. The goal is to be free and comfortable in your own skin, and only then submitting yourself to the collective, as a full being and not as a fragment.”

[**Z ZEGNA**](https://www.zegna.us/us-en/home.html) shirt.

At first blush, Maru Coffee is an unlikely setting for existential musings. The edges are too crisp, the decor too Spartan, the light too bright. But it may just possess what the waiter from Hemingway’s “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place” knew to be necessary for dwelling on nothingness and questions of meaning.

“That’s what’s fun about embracing the chaos—things become more meaningful. In every interaction, Ben is the most present person. He looks vacant, but only to our eyes. It’s a nihilistic optimism, someone who’s gotten to base zero, to accept that everything is meaningless, and to rebuild the world from that framework.”

Yeun has previously discussed how Lee Chang-dong hoped his “American-ness” would lend a certain dissonance to his performance. Interestingly, Yeun felt “at home” for the first time playing Ben, and yet was able to function as a kind of_other_ for his Korean audience.

“Ben’s otherness,” says Yeun, “is rooted in the tension between individualism and collectivism. Americans live very singularly. I remember growing up as a Korean kid in predominately white neighborhoods and talking to my friends, and someone saying, ‘If I don’t get a job when I turn eighteen, my mom’s going to kick me out of the house and won’t help with college.’ To a Korean kid that sounds _crazy_. We’re lucky because that’s where collectivism serves us: everyone’s grinding for everyone else.

“But that kid getting kicked out is also beautiful because it respects the individual. Few Koreans get to experience that. You’re usually serving the whole and have to play your required part. But in the U.S. there’s this feeling that you can inhabit your own space. I feel much more like an individual here than I do in Korea.

Yeun sees the West as hungry for meaning and community, while the East seeks an easing of strictures. “I’ve met many young Koreans and they feel primed to transgress cultural boundaries,” he says. “The internet has really allowed East and West to cross-pollinate. The West is trying to grasp collectivism, and I think that’s what the West needs. And people in Asia are grasping their individualism. It’s cool to see that happening.”

They often mean well—they’re trying to give solace to those who feel alone. But they can easily become traps, because if you stay in your safe space, you never deal with the trauma that caused you to seek it out in the first place. The goal is to be free and comfortable in your own skin, and only then submitting yourself to the collective, as a full being and not as a fragment.”

[**Z ZEGNA**](https://www.zegna.us/us-en/home.html) suit and shirt.

The hope is to find that golden balance between collectivism and individualism. “If we got to real balance, it’d be beautiful,” says Yeun. “But that’s almost utopic.” He worries that a tendency to swing towards extremes may be hardwired in the system.

But what’s impossible in life is sometimes realized in art. During filming, director Lee would often approach his cast and say, simply, “Balance.” Certainly, every scene does feel perfectly weighed and measured.

“The dude is like a Zen master,” says Yeun. “And that equanimity matters because he’s a 64-year old man telling a story about the youth, and not telling them who they are, but rather telling them, ‘I’m giving you the space to express who you are to me so that I can help _you_ craft the story.’”

Balance, as a theme, features prominently in Murakami’s short story. The unnamed character that _Burning_’s Ben is based on speaks of his arson as a force of nature. “They’re waiting to be burned. I’m simply obliging... Just like the rain. The rain falls. Streams swell. Things get swept along.” His destructive acts are central to the balance of his “simultaneity,” his sense of existing everywhere at once, unbounded by time. “Without such balance,” he says, “I don’t think we could go on living.” The translation of this theme into _Burning_is nothing if not elegant.

\*\*\*

One of the stranger moments in _Burning_ comes when Jong- su stalks Ben at the latter’s church. Whether Ben is a killer or a ritual womanizer, his presence there feels utterly dissonant. I ask Yeun, who grew up in a devoutly Christian home, what role faith plays in his life.

“Faith, for me, is an ever-changing road. I’m very thankful that I got to study religion; it gave me a lot of information, although I didn’t gain much wisdom. But as I’ve grown older, having fallen away from the Church, I find myself being drawn back to it under different pretenses. Not that I need it to tell me how to live, but I want to carefully consider what the Christian Bible is trying to say. Or even the Qur’an, or the Torah, or Buddhist scripture—they’re all talking about the inherent wisdom of doing what you are meant to do in this universe, and going with its flow, as opposed to warring against it. At the moment, I’ve been re-reading passages in the Bible, and I’m like, _Whoa_, that means something completely different to me now. I really understand the wisdom of this passage.”

\*\*\*

[**Z ZEGNA**](https://www.zegna.us/us-en/home.html) suit and shirt.

The hope is to find that golden balance between collectivism and individualism. “If we got to real balance, it’d be beautiful,” says Yeun. “But that’s almost utopic.” He worries that a tendency to swing towards extremes may be hardwired in the system.

But what’s impossible in life is sometimes realized in art. During filming, director Lee would often approach his cast and say, simply, “Balance.” Certainly, every scene does feel perfectly weighed and measured.

“The dude is like a Zen master,” says Yeun. “And that equanimity matters because he’s a 64-year old man telling a story about the youth, and not telling them who they are, but rather telling them, ‘I’m giving you the space to express who you are to me so that I can help _you_ craft the story.’”

Balance, as a theme, features prominently in Murakami’s short story. The unnamed character that _Burning_’s Ben is based on speaks of his arson as a force of nature. “They’re waiting to be burned. I’m simply obliging... Just like the rain. The rain falls. Streams swell. Things get swept along.” His destructive acts are central to the balance of his “simultaneity,” his sense of existing everywhere at once, unbounded by time. “Without such balance,” he says, “I don’t think we could go on living.” The translation of this theme into _Burning_is nothing if not elegant.

\*\*\*

One of the stranger moments in _Burning_ comes when Jong- su stalks Ben at the latter’s church. Whether Ben is a killer or a ritual womanizer, his presence there feels utterly dissonant. I ask Yeun, who grew up in a devoutly Christian home, what role faith plays in his life.

“Faith, for me, is an ever-changing road. I’m very thankful that I got to study religion; it gave me a lot of information, although I didn’t gain much wisdom. But as I’ve grown older, having fallen away from the Church, I find myself being drawn back to it under different pretenses. Not that I need it to tell me how to live, but I want to carefully consider what the Christian Bible is trying to say. Or even the Qur’an, or the Torah, or Buddhist scripture—they’re all talking about the inherent wisdom of doing what you are meant to do in this universe, and going with its flow, as opposed to warring against it. At the moment, I’ve been re-reading passages in the Bible, and I’m like, _Whoa_, that means something completely different to me now. I really understand the wisdom of this passage.”

\*\*\*

[**BOSS**](https://www.hugoboss.com/us/) suit and shirt and [**PIERRE HARDY**](https://www.pierrehardy.com) shoes.

In a late scene in _Burning_, Hae-mi performs a dance she learned in Kenya. The dance—which enacts two “hungers”—is adapted from Sir Laurens van der Post’s study of the Kalahari Bushmen. “There is the Great Hunger and the Little Hunger,” writes van der Post. “The Little Hunger wants food for the belly; but the Great Hunger, the greatest hunger of all, is the hunger for meaning... There is nothing wrong in searching for happiness. But meaning is of far more comfort to the soul.”

It’s a revelatory scene. Jong-su observes Hae-mi’s movements with affection; he longs for her, but also through her, as if she’s come to mediate his pursuit of meaning. Ben, however, observes her with an unreadable expression. We’re left questioning whether this man, who has never known physical hunger, has also never hungered for meaning.

Eager to lock up and get on with their evening, the baristas finally ask us to leave. We finish our conversation outside in an alleyway. It is dusk and the air is refreshingly cool. Yeun’s driver waits nearby, his black blazer unbuttoned to reveal a comically long ivory tie riding the curve of his belly.

The Great Hunger is sated in different ways for each of us. Steven Yeun tries to feed it by “flowing with the universe as it comes.”

“I acknowledge that I’m in a very privileged position to say something like that,” he says. “I’m not suffering on my daily so that it’d be hard to go with the flow. But it feels purposeful. My favorite verse is Romans 12:2, ‘Do not conform to the pattern of this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your mind, then you will be able to test God’s good and perfect will.’ In understanding that, I feel that I’m in the flow, that what I desire is equivalent to what the universe desires in my life, so then I’m just an agent of the universe, I’m a wave in the ocean. That’s where I’m trying to find my Zen—this constant, careful consideration of myself. Every time I’ve tried to push against the current, it never works out, and I’m always devastated by it. But every time I just let go to the process, it becomes this magical lesson or experience.”

* * *

Photographed and filmed by: Shane Mccauley.

Stylist: Nicolas Klam at The Visionaries Agency.

Groomer: Sheridan Ward using Oribe at Cloutier Remix.

Photography Assistant: Jake Harrison.

Styling Assistant: Kyle Huewe.

[

sold out

](/store/issue-164)

[Issue 164](/store/issue-164)

$15.95

Outside Cover:

Select Outside Cover CAYETANO FERRERJULIANNE MOOREGARRETT HEDLUNDCOLSON BAKER

CAYETANO FERRER JULIANNE MOORE GARRETT HEDLUND COLSON BAKER

Add To Cart

document.querySelector('.product-block .product-block').classList.add('is-first-product-block');

[**BOSS**](https://www.hugoboss.com/us/) suit and shirt and [**PIERRE HARDY**](https://www.pierrehardy.com) shoes.

In a late scene in _Burning_, Hae-mi performs a dance she learned in Kenya. The dance—which enacts two “hungers”—is adapted from Sir Laurens van der Post’s study of the Kalahari Bushmen. “There is the Great Hunger and the Little Hunger,” writes van der Post. “The Little Hunger wants food for the belly; but the Great Hunger, the greatest hunger of all, is the hunger for meaning... There is nothing wrong in searching for happiness. But meaning is of far more comfort to the soul.”

It’s a revelatory scene. Jong-su observes Hae-mi’s movements with affection; he longs for her, but also through her, as if she’s come to mediate his pursuit of meaning. Ben, however, observes her with an unreadable expression. We’re left questioning whether this man, who has never known physical hunger, has also never hungered for meaning.

Eager to lock up and get on with their evening, the baristas finally ask us to leave. We finish our conversation outside in an alleyway. It is dusk and the air is refreshingly cool. Yeun’s driver waits nearby, his black blazer unbuttoned to reveal a comically long ivory tie riding the curve of his belly.

The Great Hunger is sated in different ways for each of us. Steven Yeun tries to feed it by “flowing with the universe as it comes.”

“I acknowledge that I’m in a very privileged position to say something like that,” he says. “I’m not suffering on my daily so that it’d be hard to go with the flow. But it feels purposeful. My favorite verse is Romans 12:2, ‘Do not conform to the pattern of this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your mind, then you will be able to test God’s good and perfect will.’ In understanding that, I feel that I’m in the flow, that what I desire is equivalent to what the universe desires in my life, so then I’m just an agent of the universe, I’m a wave in the ocean. That’s where I’m trying to find my Zen—this constant, careful consideration of myself. Every time I’ve tried to push against the current, it never works out, and I’m always devastated by it. But every time I just let go to the process, it becomes this magical lesson or experience.”

* * *

Photographed and filmed by: Shane Mccauley.

Stylist: Nicolas Klam at The Visionaries Agency.

Groomer: Sheridan Ward using Oribe at Cloutier Remix.

Photography Assistant: Jake Harrison.

Styling Assistant: Kyle Huewe.

[

sold out

](/store/issue-164)

[Issue 164](/store/issue-164)

$15.95

Outside Cover:

Select Outside Cover CAYETANO FERRERJULIANNE MOOREGARRETT HEDLUNDCOLSON BAKER

CAYETANO FERRER JULIANNE MOORE GARRETT HEDLUND COLSON BAKER

Add To Cart

document.querySelector('.product-block .product-block').classList.add('is-first-product-block');

.jpg)