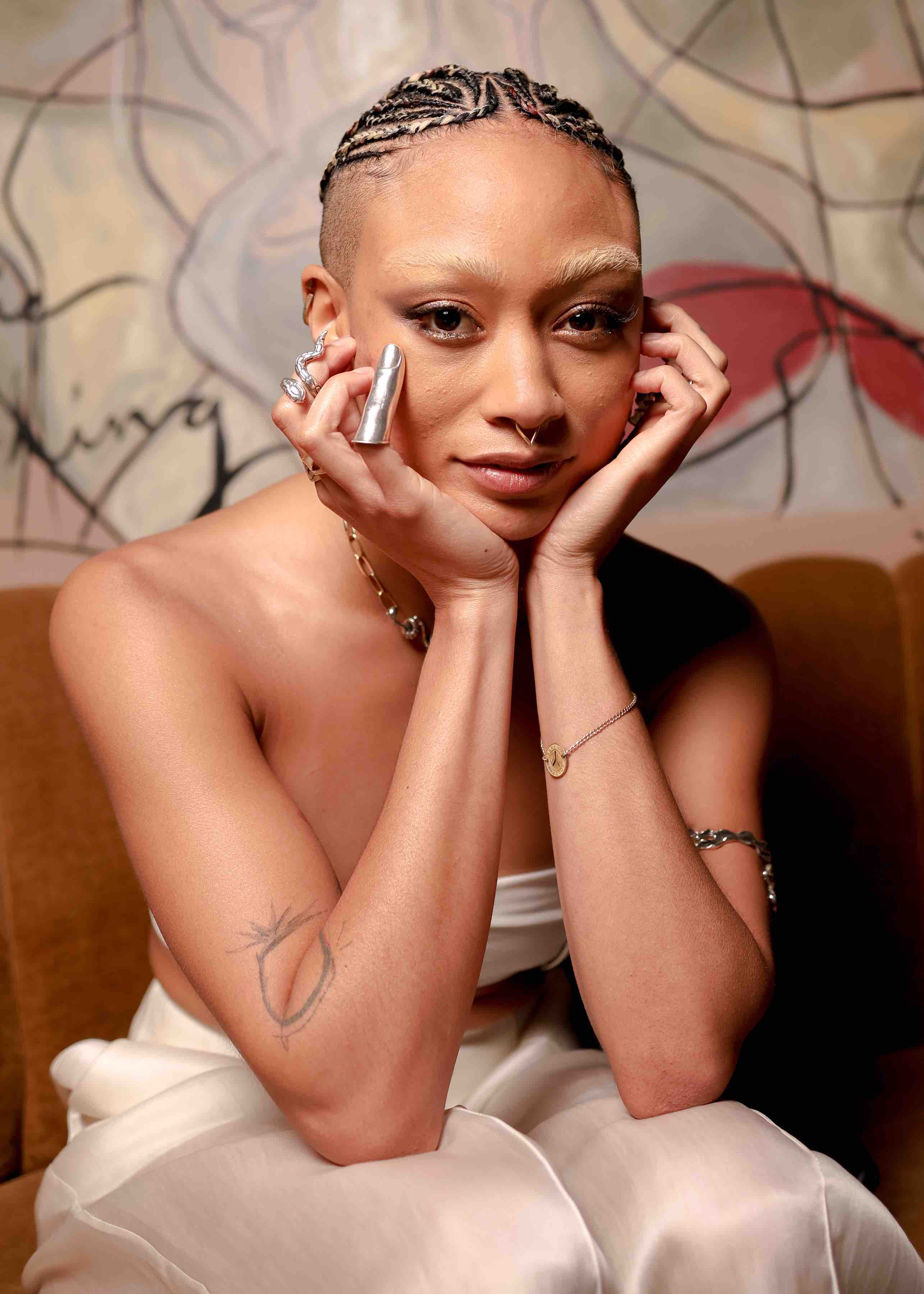

Photography by Michael Tighe at MichaelTighePhotography.com.

[](https://flaunt-mag.squarespace.com/config/pages/587fe9d4d2b857e5d49ca782#)[](https://flaunt-mag.squarespace.com/config/pages/587fe9d4d2b857e5d49ca782#)

Chris Milk

Onward, Dystopia Awaits

Watch Chris Milk’s music video for Kanye West’s “All Falls Down” and you can see it: the video artist’s foundation for a different kind of narrative. Invited to experience through someone else’s eyes—in this case, Kanye’s—there

_you_

are seeing Stacey Dash off at the airport, a tourist spilling mustard on

_your_

pink oxford,

_your_

eyes going blurry in the bathroom as you squint into the mirror.

Fast-forward a decade to last year’s Sundance Film Festival where Milk took immersive musical experience to a whole new level. He teamed up with Beck to reimagine David Bowie’s “Sound and Vision” for viewing on the Oculus Rift. Milk filmed the concert in 360 degrees with binaural microphones to show what Virtual Reality (VR) headsets are capable beyond just rendering _Call of Duty_ more realistic. Viewers could toggle instantly between different angles, and thanks to the innovative use of microphones, the source sound changed as well. You could sit in the middle of the strings section, then suddenly transport yourself above the stage.

Milk tells me this was not a normal concert movie experience. “A number of people have cried watching it in the VR headset and no one’s cried that I know of watching the linear YouTube version.” Milk himself said that his first experience with VR—at USC’s Institute for Creative Technologies out in Playa Vista—was similarly profound. He viewed a scene created by “immersive journalist” Nonny de la Peña, and despite it having all the visual sophistication of the Dire Straits “Money for Nothing” music video, he says, “It was so affecting. It was exactly what I was hoping it would be.”

How can such a deep reaction be prompted by simply strapping into a bulky headset and listening? When asked, he tells me that what’s fundamentally different about this medium is that it’s moving beyond visual narratives as something to be seen through a rectangle. Instead artists and programmers are hacking very deep and ancient parts of the brain, essentially bypassing the traditional covenant between media’s consumers and creators that Coleridge called “suspension of disbelief.” With VR, the “poetic faith” required of cinemagoers or readers can be effaced by the art of scientific manipulation that a fully mature VR unit is capable of.

For those familiar with the dystopian fiction surrounding VR, this may sound eerily familiar, and it’s likely that our entertainment future will present to us the opposite problem Coleridge faced. VR’s ability to feign veracity will require us to remind ourselves constantly that we are not where our headset is telling us we are. Milk says, half-jokingly, “I may in fact be actively creating our dystopian future.” He hastens to add, much more seriously, that even if such potential futures are leagues away and perhaps the result of a bit of scaremongering, one very real problem science fiction has touched on is the aloneness: “In its current form \[VR\] is isolating technology.” Filmmakers and designers must quickly find ways to make the experience interactive, lest we all end up sitting in our bedrooms with headsets strapped to our faces for the rest of eternity.

But before we have to start worrying about choosing between the red or blue pills, more prosaic problems loom. There are _Cahiers du cinéma_\-type theoretical ones, like how much narrative structures and ideas of perspective change when your viewer is inside your film; and the technical, such as making sure people don’t throw up when the camera suddenly turns. Although Milk has never seen someone throw up in a VR headset, he’s seen plenty of people get quite nauseous from what is known as “brain-sheer.”

But even technology-induced motion sickness can be interesting. “Your eyes are seeing the world moving in a way that does not correlate to the vestibular sacs inside your inner ear telling your brain your head is actually moving.” Translation: When you walk forward in reality, sensory cells in your inner ear responsible for balance and equilibrium translate that motion for your brain. In VR, there’s only the implication of actual motion; your brain believes you’re turning your head right, for example, when really it’s just the camera. Signals thus crossed, and voila: vomit. This is a primeval process, and Milk laments that now “caveman shit is fucking up our future storytelling world because it stops us from being able to move the camera in certain ways.” For now, anyway.

Like any good explorer, Milk sees problems like these as things to understand and eventually overcome. Right now filmmakers are “totally just poking around in the dark,” but the more comfortable they become with working beyond the confines of the rectangles we’ve grown up with, the more they can focus on “trying to figure out what comes after cinema.”

Here’s hoping it doesn’t wind up like something out of a Philip K. Dick novel.

Photography by Michael Tighe at MichaelTighePhotography.com.

Photography by Michael Tighe at MichaelTighePhotography.com.

[](https://flaunt-mag.squarespace.com/config/pages/587fe9d4d2b857e5d49ca782#)[](https://flaunt-mag.squarespace.com/config/pages/587fe9d4d2b857e5d49ca782#)

Chris Milk

Onward, Dystopia Awaits

Watch Chris Milk’s music video for Kanye West’s “All Falls Down” and you can see it: the video artist’s foundation for a different kind of narrative. Invited to experience through someone else’s eyes—in this case, Kanye’s—there

_you_

are seeing Stacey Dash off at the airport, a tourist spilling mustard on

_your_

pink oxford,

_your_

eyes going blurry in the bathroom as you squint into the mirror.

Fast-forward a decade to last year’s Sundance Film Festival where Milk took immersive musical experience to a whole new level. He teamed up with Beck to reimagine David Bowie’s “Sound and Vision” for viewing on the Oculus Rift. Milk filmed the concert in 360 degrees with binaural microphones to show what Virtual Reality (VR) headsets are capable beyond just rendering _Call of Duty_ more realistic. Viewers could toggle instantly between different angles, and thanks to the innovative use of microphones, the source sound changed as well. You could sit in the middle of the strings section, then suddenly transport yourself above the stage.

Milk tells me this was not a normal concert movie experience. “A number of people have cried watching it in the VR headset and no one’s cried that I know of watching the linear YouTube version.” Milk himself said that his first experience with VR—at USC’s Institute for Creative Technologies out in Playa Vista—was similarly profound. He viewed a scene created by “immersive journalist” Nonny de la Peña, and despite it having all the visual sophistication of the Dire Straits “Money for Nothing” music video, he says, “It was so affecting. It was exactly what I was hoping it would be.”

How can such a deep reaction be prompted by simply strapping into a bulky headset and listening? When asked, he tells me that what’s fundamentally different about this medium is that it’s moving beyond visual narratives as something to be seen through a rectangle. Instead artists and programmers are hacking very deep and ancient parts of the brain, essentially bypassing the traditional covenant between media’s consumers and creators that Coleridge called “suspension of disbelief.” With VR, the “poetic faith” required of cinemagoers or readers can be effaced by the art of scientific manipulation that a fully mature VR unit is capable of.

For those familiar with the dystopian fiction surrounding VR, this may sound eerily familiar, and it’s likely that our entertainment future will present to us the opposite problem Coleridge faced. VR’s ability to feign veracity will require us to remind ourselves constantly that we are not where our headset is telling us we are. Milk says, half-jokingly, “I may in fact be actively creating our dystopian future.” He hastens to add, much more seriously, that even if such potential futures are leagues away and perhaps the result of a bit of scaremongering, one very real problem science fiction has touched on is the aloneness: “In its current form \[VR\] is isolating technology.” Filmmakers and designers must quickly find ways to make the experience interactive, lest we all end up sitting in our bedrooms with headsets strapped to our faces for the rest of eternity.

But before we have to start worrying about choosing between the red or blue pills, more prosaic problems loom. There are _Cahiers du cinéma_\-type theoretical ones, like how much narrative structures and ideas of perspective change when your viewer is inside your film; and the technical, such as making sure people don’t throw up when the camera suddenly turns. Although Milk has never seen someone throw up in a VR headset, he’s seen plenty of people get quite nauseous from what is known as “brain-sheer.”

But even technology-induced motion sickness can be interesting. “Your eyes are seeing the world moving in a way that does not correlate to the vestibular sacs inside your inner ear telling your brain your head is actually moving.” Translation: When you walk forward in reality, sensory cells in your inner ear responsible for balance and equilibrium translate that motion for your brain. In VR, there’s only the implication of actual motion; your brain believes you’re turning your head right, for example, when really it’s just the camera. Signals thus crossed, and voila: vomit. This is a primeval process, and Milk laments that now “caveman shit is fucking up our future storytelling world because it stops us from being able to move the camera in certain ways.” For now, anyway.

Like any good explorer, Milk sees problems like these as things to understand and eventually overcome. Right now filmmakers are “totally just poking around in the dark,” but the more comfortable they become with working beyond the confines of the rectangles we’ve grown up with, the more they can focus on “trying to figure out what comes after cinema.”

Here’s hoping it doesn’t wind up like something out of a Philip K. Dick novel.

[](https://flaunt-mag.squarespace.com/config/pages/587fe9d4d2b857e5d49ca782#)[](https://flaunt-mag.squarespace.com/config/pages/587fe9d4d2b857e5d49ca782#)

Chris Milk

Onward, Dystopia Awaits

Watch Chris Milk’s music video for Kanye West’s “All Falls Down” and you can see it: the video artist’s foundation for a different kind of narrative. Invited to experience through someone else’s eyes—in this case, Kanye’s—there

_you_

are seeing Stacey Dash off at the airport, a tourist spilling mustard on

_your_

pink oxford,

_your_

eyes going blurry in the bathroom as you squint into the mirror.

Fast-forward a decade to last year’s Sundance Film Festival where Milk took immersive musical experience to a whole new level. He teamed up with Beck to reimagine David Bowie’s “Sound and Vision” for viewing on the Oculus Rift. Milk filmed the concert in 360 degrees with binaural microphones to show what Virtual Reality (VR) headsets are capable beyond just rendering _Call of Duty_ more realistic. Viewers could toggle instantly between different angles, and thanks to the innovative use of microphones, the source sound changed as well. You could sit in the middle of the strings section, then suddenly transport yourself above the stage.

Milk tells me this was not a normal concert movie experience. “A number of people have cried watching it in the VR headset and no one’s cried that I know of watching the linear YouTube version.” Milk himself said that his first experience with VR—at USC’s Institute for Creative Technologies out in Playa Vista—was similarly profound. He viewed a scene created by “immersive journalist” Nonny de la Peña, and despite it having all the visual sophistication of the Dire Straits “Money for Nothing” music video, he says, “It was so affecting. It was exactly what I was hoping it would be.”

How can such a deep reaction be prompted by simply strapping into a bulky headset and listening? When asked, he tells me that what’s fundamentally different about this medium is that it’s moving beyond visual narratives as something to be seen through a rectangle. Instead artists and programmers are hacking very deep and ancient parts of the brain, essentially bypassing the traditional covenant between media’s consumers and creators that Coleridge called “suspension of disbelief.” With VR, the “poetic faith” required of cinemagoers or readers can be effaced by the art of scientific manipulation that a fully mature VR unit is capable of.

For those familiar with the dystopian fiction surrounding VR, this may sound eerily familiar, and it’s likely that our entertainment future will present to us the opposite problem Coleridge faced. VR’s ability to feign veracity will require us to remind ourselves constantly that we are not where our headset is telling us we are. Milk says, half-jokingly, “I may in fact be actively creating our dystopian future.” He hastens to add, much more seriously, that even if such potential futures are leagues away and perhaps the result of a bit of scaremongering, one very real problem science fiction has touched on is the aloneness: “In its current form \[VR\] is isolating technology.” Filmmakers and designers must quickly find ways to make the experience interactive, lest we all end up sitting in our bedrooms with headsets strapped to our faces for the rest of eternity.

But before we have to start worrying about choosing between the red or blue pills, more prosaic problems loom. There are _Cahiers du cinéma_\-type theoretical ones, like how much narrative structures and ideas of perspective change when your viewer is inside your film; and the technical, such as making sure people don’t throw up when the camera suddenly turns. Although Milk has never seen someone throw up in a VR headset, he’s seen plenty of people get quite nauseous from what is known as “brain-sheer.”

But even technology-induced motion sickness can be interesting. “Your eyes are seeing the world moving in a way that does not correlate to the vestibular sacs inside your inner ear telling your brain your head is actually moving.” Translation: When you walk forward in reality, sensory cells in your inner ear responsible for balance and equilibrium translate that motion for your brain. In VR, there’s only the implication of actual motion; your brain believes you’re turning your head right, for example, when really it’s just the camera. Signals thus crossed, and voila: vomit. This is a primeval process, and Milk laments that now “caveman shit is fucking up our future storytelling world because it stops us from being able to move the camera in certain ways.” For now, anyway.

Like any good explorer, Milk sees problems like these as things to understand and eventually overcome. Right now filmmakers are “totally just poking around in the dark,” but the more comfortable they become with working beyond the confines of the rectangles we’ve grown up with, the more they can focus on “trying to figure out what comes after cinema.”

Here’s hoping it doesn’t wind up like something out of a Philip K. Dick novel.