Rembrandt van Rijn. “The Storm on the Sea of Galilee.” (1633). 161.7 x 129.8 cm. Oil on canvas. Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Courtesy The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.

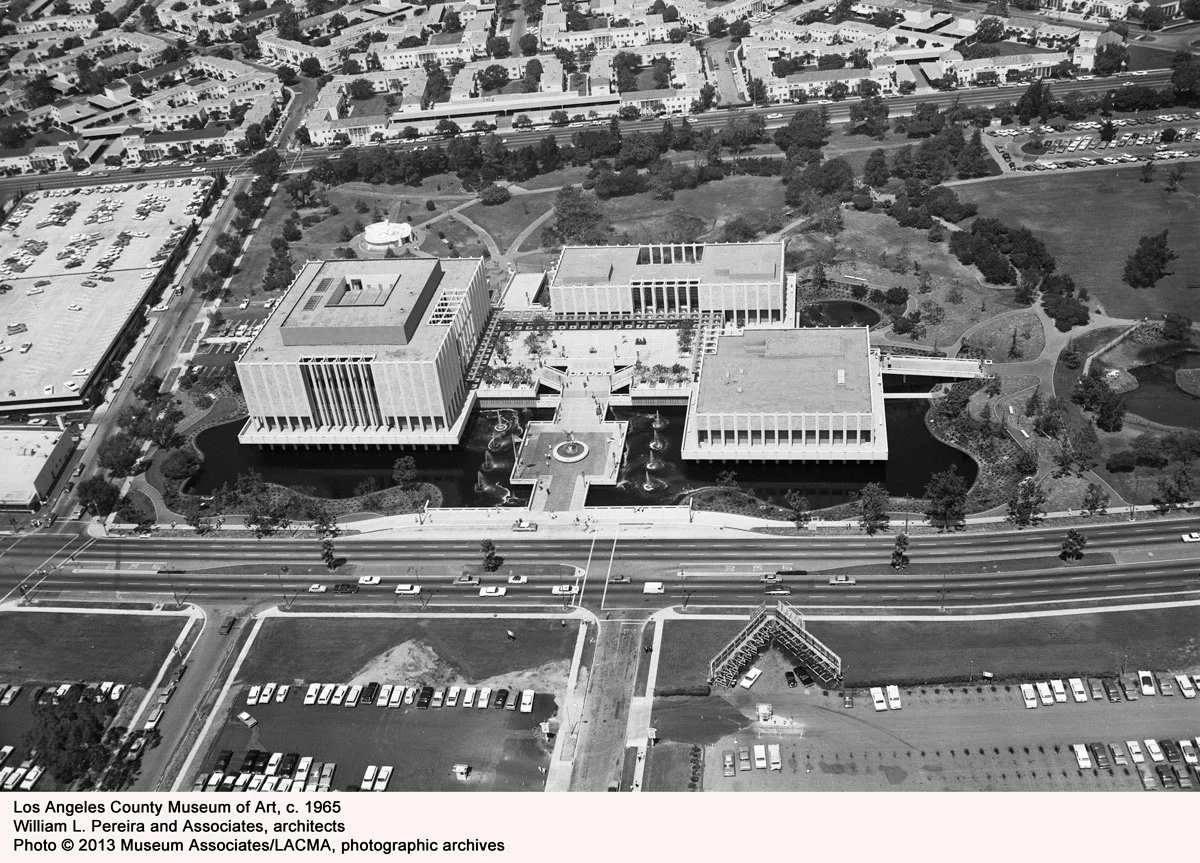

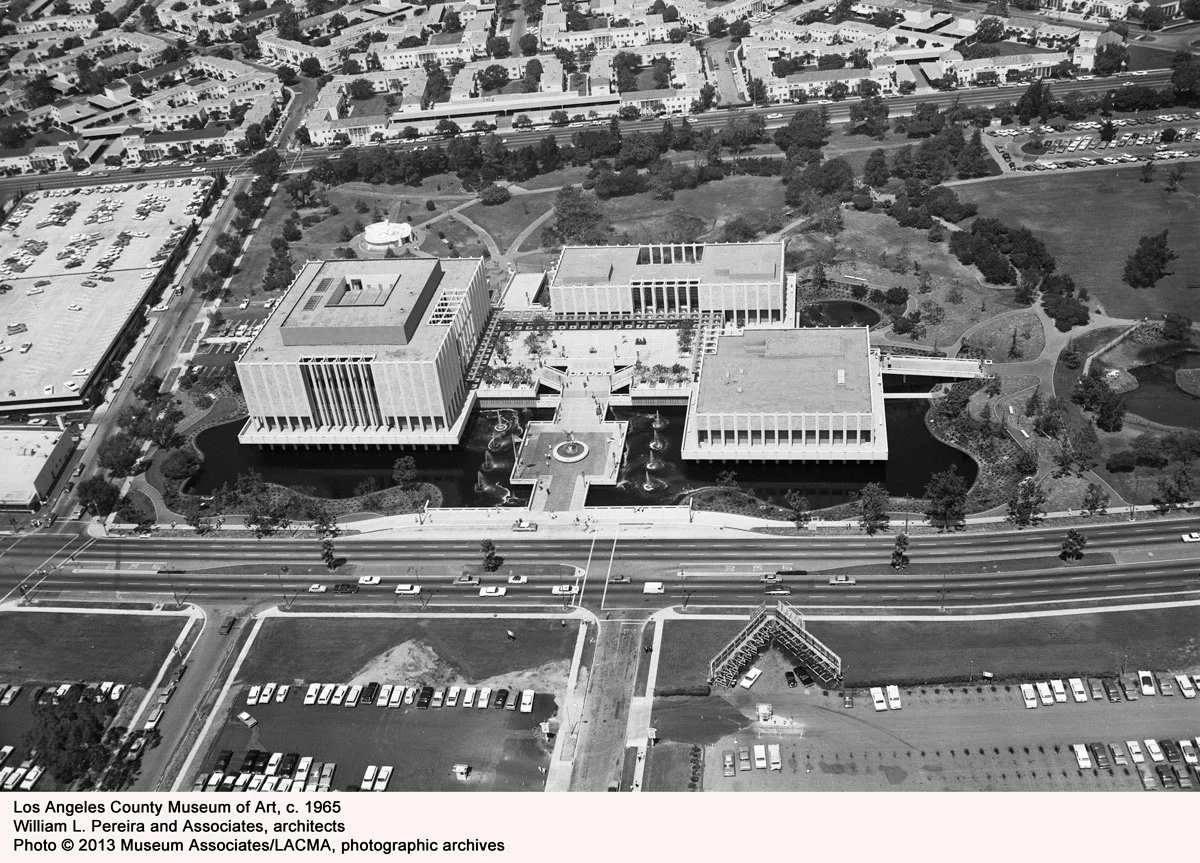

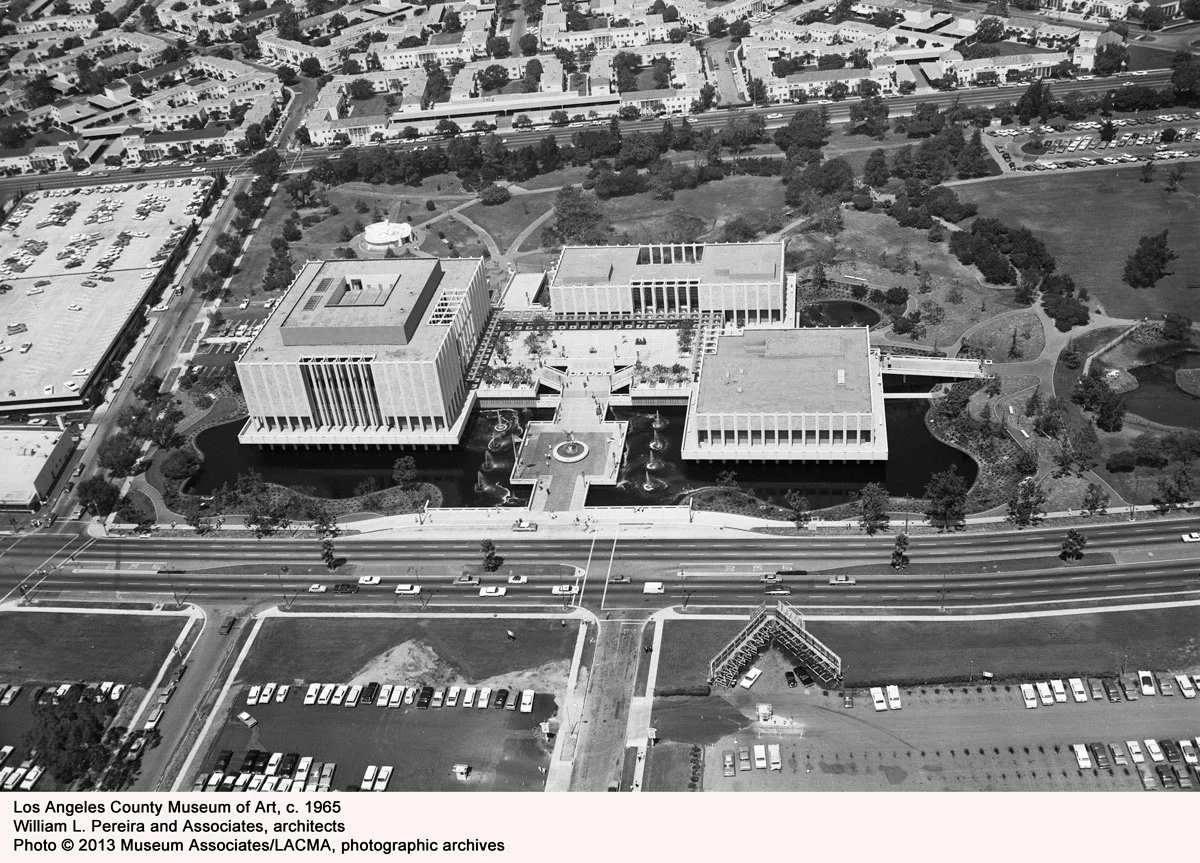

Aerial view Los Angeles County Museum of Art. (c. 1965). William L. Pereira and Associates, architects. Photo © 2013 Museum Associates/LACMA, photographic archives.

Jan Vermeer. “The Concert.” (1658–1660) 72.5 x 64.7 centimeters. Oil on canvas.

Courtesy The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.

The Painter of Vatican 238. “Kalpis (Water Vessel) with Pirates Transforming into Dolphins,” (520‑510 BCE). Courtesy the Toledo Museum of Art.

Maurizio Cattelan. “Another Fucking Readymade,” (1996). Crated and wrapped gallery contents. Variable dimensions. Courtesy Maurizio Cattelan’s Archive.

[](#)[](#)

The Heist, The Larcenist, The Van Goyen, The Purloined

The Thief & His Guide How To Steal From LACMA

The criminality of theft has been tempered by literary romanticism of the thief since Prometheus’ theft of fire enabled progress within civilization.

Why do we glorify the larcenist? Is it the thrill in a world of “no”s to discover that nearly everything is obtainable? The heroic outlaw running gallantly through the forest, rakish feather in cap, aiding the poor with the unauthorized loot of the rich lends a sense of justice to our cold universe. And the art thief is held in even higher esteem; always near-genius, and often casually speeding off in “one of those red Italian things.”

In truth, the motivations for these crimes, committed by these criminals, often only serve to perplex. Kids steal sculpture for scrap metal; war-torn countries face nihilistic looters; a lowly assistant quietly swipes a painting from his mentor.

In the face of these nonlinear events we present: a few thoughts on art theft.

I wish I could tell you that the best way to steal art from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art would involve some hi-tech gadgetry and ingenious, Thomas Crownian sleight-of-hand. Sure, you could slip into the security control room disguised as a custodian and attach a scrambler to the CCTV to send the video into continuous loop. You could hack into the computer system to cut off electricity to the room in question, and have your accomplice lift the painting off the wall (in case you were wondering, I’d swipe Magritte’s “The Treachery of Images,” take it home, and stage secret discussions of Foucault’s interpretation of it, while serving tapas and smoking shisha from a water pipe). You’d pop it out of its frame and make a break for the door, just as another associate pulls the fire alarm. Such a plan just might work, and it’s the more cinematic approach.

But the popular perception of art theft is stuck back in the Victorian era, when loan dexterous thieves with non-violent, gentlemanly aspirations stole art for reasons more ideological than financial. The reality is that, since the Second World War, the majority of art crime has been perpetrated by, or on behalf of, organized crime groups. For decades, art crime has been the third-highest-grossing criminal trade worldwide, behind only drugs and arms. It even funds terrorism, with Mohammed Atta, of the 9/11 attacks, known to have sought buyers for looted Afghani antiquities, profits from which he was planning to use to buy a plane to crash into buildings. In art theft, it is often not just the art that is at stake.

All these uncomfortable truths about art theft mean that art is most effectively stolen via the blunt instrument approach—what I call a “blitz theft.” It is the mark of organized crime’s involvement in a heist, and may be seen from the Munch Museum to the Bührle Collection, from the National Gallery of Sweden to the Museum of Eastern and Western Art of Odessa. In each incident, armed and masked assailants wielding automatic firearms burst into the museum during opening hours. They shouted the shocked visitors and guards to the floor, ripped a few artworks off the walls, and made a swift exit. What of the million-dollar alarm systems, you ask? Oh sure, they went off. But average police response time in cities is three to five minutes, and that’s on a good day. So if the thieves got out in less than three minutes, the alarms didn’t matter. They were simply expensive noise boxes. By the time help arrived, the thieves were long gone, sometimes in dramatic fashion. At the National Gallery of Sweden, they got away via a speedboat that awaited them in the bay behind the museum.

By night, museums can lock themselves down like bank vaults. Precious few thieves are skillful, or foolish, enough to steal from museums when they’re closed. But during open hours, these museums must give the public as comfortable access as possible to their collections, while still keeping them safe—a tough balancing act. Only stoppable by clogging up the entrance to museums with airport-style security, blitz thefts represent the greatest and most difficult threat. Security guards are not expected to engage in firefights with burglars, nor should they turn a theft into a potential gun battle or hostage situation. Art thefts are rare enough that most museums are never threatened by them, so it’s natural that security guards might “switch off” after a decade-long career without a single real incident. Organized criminals know this, and thus turn to smash-and-grab techniques, while the world expects art thieves to slink around in leather bodysuits, dodging lasers and dangling upside-down from skylights. The scary art thieves are the armed gangsters, who aim to turn stolen art into drugs and arms, illicit art funding the more sinister activities of criminal gangs and syndicates. The scariest of all are those who loot antiquities, tear out the treasures of the earth, and sell them to fund terrorist attacks.

LACMA should keep its Magritte. But let the museum be warned—all the alarms in the world won’t protect against blitz thefts. When the defenders expect the barbarians to come in stealth by night, the cleverest barbarians barge straight in through the front door.

\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_

From the illustrious Robert Wittman, former FBI agent who specialized in art theft cases and aided in the recovery of $300 million worth of stolen art:

_In the \[Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum Heist\] in 1990, they took a number of paintings that were actually in their frames and a couple that were on a stretcher. They actually cut out a couple very big Rembrandts and they rolled those up. Usually when we see people cutting paintings out of frames and rolling them, we know that they’re not professionals because that’s the quickest way to destroy a painting._

During the March 18th 1990 heist at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, two men dressed as police officers infiltrated the closed museum, bound the two on duty security guards, and made off with 13 works worth $500 million. “The Concert,” one of 36 known Vermeer’s in existence, was included in the loot and has yet to resurface in the public market, likely due to the high-status of the theft and its characteristic mark of a stolen image: being cut from the frame.

Artist Sophie Calle, alludes to this aspect of the theft in her most recent exhibition, “Last Seen” currently on view at the Gardner Museum (October 24, 2013–March 3, 2014). In the exhibit of photographs, anonymous viewers confront the butchering, looking to the empty frames still hung on the walls.

All 13 works remain unrecovered.

\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_

THE PAINTING, THE THIEF, THE ARTIST, THE MUSEUM, & THEIR LEGENDS: FOUR MAJOR WORKS OF LOSS

Fiction by Andrew Stark History by Chinnie Ding

THE PAINTING: REMBRANDT VAN RIJN’S “DANAË”

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487268485002-1QJBVIBN7ARBFZVVWMNG/GE_723.jpg)

_There exists no vocabulary for certain events, no words strong enough. Language gets reduced to something primitive, monosyllabic and untranslatable, the animal babble of intense lament. When the man appeared and flashed his blade, that gristled Lithuanian with eyes like stones, the crowd surrounding us became one homogenized embranglement of frenzy and fear. They communicated their panic through a series of yelps, slanting to the gallery floor. The man slashed my stomach and my thigh as if I were a lover who’d slighted him, some vile propinquity. There was passion in his redbrick face. Then, in a flourish, he pulled from his coat a bottle of sulfuric acid and crossed it over my eight-by-ten expanse in deranged anointment. Guards wrestled him to his knees, a strange gesture of supplication. Everyone, as they say, was speechless._

_That very same day, the restoration process began by a number of people from the State Hermitage’s Laboratory of Expert Restoration of Easel Paintings. They consulted with chemists about my face, settled debates regarding the scientific methodology of my right arm. After twelve years, they said, I was complete. But something had been lost—the essence of my creator’s original devotion—and I became nothing more than a tourist attraction. It doesn’t matter, I suppose, because even the most memorable lives are forgotten._

Acquired in 1772 by Catherine the Great herself for the Hermitage’s founding collection, Rembrandt van Rijn’s “Danaë” presents an image we shouldn’t be privy to. Pent up in a tower by her father to keep her chaste, the Greek princess of legend rises from her bed in anticipation as Zeus, in the form of a golden haze, enters the chamber to have his way. Her life-size, soft-edged body, flushed cheeks, and ambiguous expression capture that stirring, secret moment when untouched desire becomes vulnerably visible—and potentially receptive. Although the semi-reclining female nude was already becoming a favored trope—see the Venuses of Giorgione, Titian, Velasquez, and iconic successors like Ingres’s “Odalique” and Manet’s “Olympia”—it was still a brave subject for the Dutch painting of Rembrandt’s time. Something about the heady naturalism of “Danaë” embarrassed several generations of Russian aristocracy, too, who periodically stowed it away from view.

In 1985, then, when a Lithuanian man named Bronius Maigis razor-slashed, then acid-splashed the canvas center, rookie psychoanalysts might have called out vicarious sexual violence. Yet Maigis himself declared it an act of political protest: He’d chosen the very day that, in 1940, Lithuania lost its independence to the USSR. All the more reason, perhaps, that the uncompromising Kremlin vetoed pessimistic museum experts to demand restoration straightaway (while censoring Maigis’s motives and shipping him to an asylum). Aided by an obscure 19th-century copy and a balm of honey and sturgeon glue, conservators would take the next 12 years to reconstruct the original’s sly and glorious provocation.

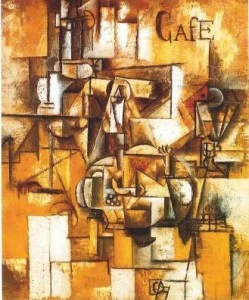

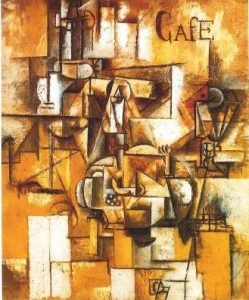

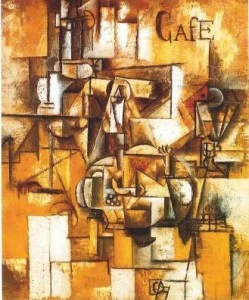

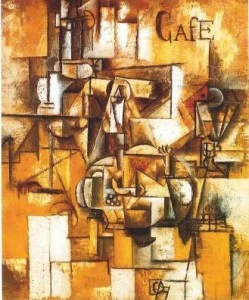

THE THIEF: PABLO PICASSO’S “LE PIGEON AUX PETIT POIS”

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487268457971-8IMRHI19OTAOFSBDC66R/3.-Picasso-Le-pigeon-aux-pois1.jpg)

_Cunts. I slipped into the Musée d’Art Moderne after lights out like I’d been invited. Because I fucking could, that’s why. It was genius. Place had a faulty alarm system and three sleeping guards. I planned for months. Swiped a Picasso, a Matisse and a few more—about €100 million worth. I’m a criminal satisfying a criminal thrill. I’m menacing, skulking, the coyote who haunts your farm. I’d just as soon massage my knife into your throat to get my pulse going. Because conscience is just a bullshit weakness that hums under the skin. It swims in your blood like red tide, crowding the coward’s heart. You think you know me—some skinny kid growing up in the projects, the cmpaћapa, putting myself to bed hungry as cries echo from my belly like frogs in the dark. Yeah, you think you know. I’m just like you, but I’ve got balls. When God calls time-out and we all quit playing, when the bombs drop and the stores are looted clean and every last generator chugs to an asthmatic halt, I’ll torch these so-called masterpieces just to keep my fucking tootsies warm._

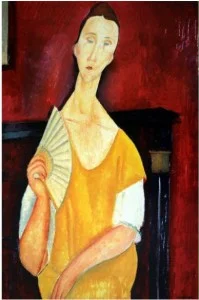

Pablo Picasso takes the prize for most pilfered artist in recorded history: to date, nearly 1,200 of his works have been reported missing by the Art Loss Register, and that’s not counting those believed to have perished in a 1943 Nazi bonfire of “degenerate art.” “Le Pigeon aux Petit Pois,” painted in 1911, was a seminal work of the cubist avant-garde movement. The work was taken by a single, stealthy thief in the spring of 2010 from the Musée d’Art Moderne. In terms of value, it’s one of the biggest heists of our time, as the thief also managed to swipe Henri Matisse’s “La Pastorale,” Amedeo Modigliani’s “La Femme à l’éventail,” Georges Braque’s “ L’Olivier Près de l’Estaque,” and Fernand Léger’s “Nature Morte aux Chandeliers.” Combined, the estimated value is $123 million, and the identity of the thief remains unknown.

The cubist work of “Le Pigeon aux Petit Pois” was a gradual continuation from Picasso’s earlier proto-cubist paintings, such as his highly regarded “Le Demoiselles d’Avignon,” characterized by the work’s disjointed shapes. Picasso was one of the pioneers of the movement (one that included Georges Braque and Fernand Leger) that was originally coined by critics as an insult. Picasso’s departure from cubism led to paintings noteworthy for bolder colors, bringing to mind another of his famous works, “Woman’s Head” that was stolen in early 2012. Painted in 1939, it was given by Picasso himself to the people of Greece in 1949, honoring their wartime resistance. The timing of its theft from the National Gallery in Athens was historic, too, in an unhappier way: Greece in early 2012 was in the throes of austerity, and museum security happened to be on a three-day strike. The lone guard on duty was a temp, blindsided by the professional seven-minute snatch.

THE ARTIST: KAREL APPEL’S “PHANTASMAGORIA NO. 162.”

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487268497574-QESE6Y6TOBUN80S0YDIG/Phantasmagoria-No.162-by-Karel-Appel.jpg-by-Karel-Appel.jpg?format=original)

_I wake each morning to a different view. Sometimes a snowcapped mountain speckled with goats, other times a city street. Or paisley patterns of rain hanging over a field, farmhouses flickering out there in the gloom like sparse constellations. Being in Heaven, it’s like changing the channel. I could be playing pinochle in my childhood home of Dapperstraat 7 one day, or munching spiced beluga lentils and niçoise toasts at some ten-acre chateau the next. Yesterday, for example, I took my coffee at the Rebel 74 on US 95. I’m usually young and healthy, lounging in a sunlit park. But I like to be old, too, hit with aches and spells and all the unpredictable flexures of the heart that make me feel human again._

_I hear things, of course, but I generally don’t pay attention to the news down there. Some of my work “went missing” years ago and was then recovered. It was a big deal, for some. I just watch my wife, Harriet, if I watch at all. Harriet wearing a trumpet gown of Alençon lace at some benefit, Harriet laying flowers on my grave at Cimetière du Père-Lachaise. Harriet smiling. But the days lose momentum._

_Sometimes, when I’m feeling particularly lonely, I surround myself with nothing, occupying a shapeless void, and I can hear the froth of distant oceans, the hiss of distant stars. I become suddenly aware of eternity’s drag, like we’re all floating around some atmospheric vacuum, surrounded by dark energy, without destination or purpose, propelled by nothing but the currents of space and the memory of time._

While it’s nice to think that art belongs to none and all, many of the world’s finest artworks are decisively hidden from public view, whether secreted in private collections or backlisted in museum depositories. As the art market’s big spenders are increasingly investors—who buy to hold then sell—the storage of art has itself become a booming industry, with an entire apparatus of free ports and logistics firms in tow. Those warehouses and shipping containers can hide illicit art traffic, too, as seen in the 2002 disappearance in transit of some 400 works by Karel Appel, shipped by the Dutch artist to his Amsterdam foundation. When that missing crate turned up nine years later at a London auction house, after Appel’s death, it was being consigned by a transport and storage company that supposedly discovered the works in a newly acquired facility.

A prolific postwar Expressionist, Appel co-founded CoBrA, an avant-garde movement (named for its founders’ hometowns: Copenhagen, Brussels, Amsterdam) that idealized boldly instinctive, childlike image-making as the basis for a radical folk art of the future. Blasts of color give his paintings a joyfully naïve, spastic quality—think Jean Dubuffet or Joan Miro on a sugar high—and his gooey, gleeful blotches often evoke boogeymen or impish imaginary friends. The lost and found “Phantasmagoria No. 162” shows Appel superimposing a print with acrylic paint and oil stick in fast, coiling scribbles—its frenetic, ghostly goblin like some spirit-animal of the artist himself, posthumously unleashed.

THE MUSEUM: “VICTORIOUS YOUTH”

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487268522800-98RIUL924FJUXZJRGRY9/Victorious-Youth.jpg)

_I am the J. Paul Getty Museum, and I adore every work of art enshrined within me. I wear them—the illusionistic portraits, those eighteenth-century French commodes, all the travelling exhibitions passing through on their Möbius trajectory from one gallery to the next—like wartime talismans, battlefield charms, something clipped to the helmet or stored near the heart. They are my children, my babies. But none compare, really, to my centerpiece, The Getty Bronze._

_He’s endured a lot, this one, like a child fed through the meat grinder of foster care. In the summer of 1964, an Italian trawler pulled up its nets about 32 miles off the coast of Fano, only to find they’d fetched my boy from the syrupy sea. The fishermen elected to sell him, which drummed up more than a little controversy. The Getty Bronze was then hidden in a bathtub, a cabbage field, beneath the wooden staircase of a local church. In 1977, a year after the death of my father, Jean Paul, the Getty acquired its Bronze and we were united. But, since a number of esoteric regulations had been breached since my boy’s discovery, Italy is attempting to secure his repatriation through some kind of transnational forfeiture action. The custody battle fuels my loss, devastation. If I knew words anchoring more weight, I would surely use them._

_I love my visitors, all my guests. The stately old woman whose curlicued up-do looks like it was styled with an ice cream scoop, the burly Midwesterner escaping the deep-fried riot of suburban redundancy, the donnish Manhattan critic who carries herself like an exclamation point and fills my rooms like a wolf whistle. But my favorites are the ones who stop and stare, really look, and I can see something register in their faces, the meditative turning of a psychological key, and I know they are seeing something inside themselves, navigating the lyrical web of dead memory. In this way my children speak to them._

L.A.’s sun- and fund-drenched Getty Museum is no stranger to scandal. In the past few decades, the art acropolis of the West Coast has been accused of tax fraud and sexual discrimination, fabricating paper trails and hushing up forgeries. The museum’s most heated controversy of late has focused on the “Victorious Youth,” a.k.a. the Getty Bronze, a virtuosic life-size bronze sculpture from the early Hellenistic period, which Italian authorities say amounts to a smuggled artifact. Nevermind that the statue was first recovered in 1964 by fishermen in the international waters of the Adriatic Sea. Or the other historical irony that, before sinking in a first-century Roman shipwreck, the statue was probably being looted out of Greece to satisfy the Grecomania of Roman collectors.

Surviving Greek bronzes are rare—most were melted down for metal—and all the rarer are those connected to the legendary Lysippos, Alexander the Great’s anointed court sculptor. Traditionally attributed to Lysippos or a gifted student, this Victorious Youth crowning himself with a laurel wreath after an athletic victory, stands rather svelte and relaxed in his confirmed triumph. It both constitutes a trophy and depicts a trophy moment.

Since 2005, amid a larger battle waged in the Italian high courts, newspaper screeds, cultural embargo threats, institutional scapegoating, and dramatic police raids on suspect dealers’ stashes across Europe—which produced damning evidence of the Getty’s fast-and-loose antiquities acquisitions—the museum has returned 49 artifacts to Italy. It refuses to give up the Getty Bronze, however, arguing it cannot repatriate what Italy never owned. While just last year an Italian court upped the ante by authorizing seizure, it’s not clear whether U.S. authorities will enforce the order. For now, the youth continues to gaze out from the Getty Villa in Malibu, insouciant to all this strife.

\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_

A BRIEF CHRONOLOGY OF LUNACY & GENIUS

Acts of creation are often linked to the celestial. The Madonna was merely a vessel for divinity. Similarly, as popular rhetoric goes, artists are merely a vessel for their own creations. And yet, the stealing of that work offers a broader placement for responsibility. Acts of theft (and the destruction attached to those acts) are mere feats of ethnologic will. In art pillaging anyone can take a try—from a sloppy teenager in the marshlands of Britain to an Eastern European cat burglar. One need not know how to paint “Poppy Flowers” by Vincent van Gogh to take a knife to its visage and free it from its frame. The gap in technique, then, is often staggering. Art Loss Register, the largest private database of stolen art in the world, documents these thefts, while aiding in the research and return of the work. Here, Art Loss Chairman Julian Radcliffe curates a list of heists—executed with lunacy, pratfalls, and puzzling moments of genius—that piqued his interest.

**1941**

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487268474599-GUWCHONAUMYF52XJP4EJ/Dr-Peter-Turner-Bust.jpg)

“Dr. Peter Turner” Mediaeval Church of St. Olave Hart Street in London, England _Suspects_: Unknown. _Method of Theft_: Walked through rubble, pulled the bust from its damaged nave after bombings by the German Luftwaffe during the London Blitz. _Status_: Recovered; 2011. Curator at the Museum of London got wind of its impending auction, tipped off church officials. Art Loss took on the case and the alabaster bust was withdrawn from the sale. _Worth_: £70,000

**1979**

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487268455097-I7UHAUD78LXU1XQRXCVZ/2.-Claesz-Still-life.jpg)

“Still Life” Pieter Claesz Private Residence of Paul Mitchell in London, England _Suspects_: Unknown. _Method of Theft_: Forced open a window, left with 10 works total. Mitchell assumed the noise was the family cat. _Status_: Unrecovered. One painting did resurface from this theft; Art Loss lawyer Christopher Marinello recovered the van Goyen. _Worth_: Combined Artwork; £1 Million

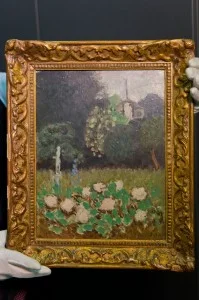

**1987**

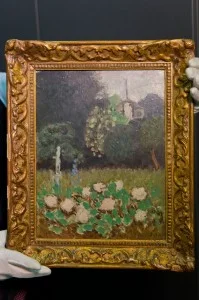

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487268491266-V3YXHT77L5CD3TOTGL2S/Matisse.jpg)

“Le Jardin” Henri Matisse Museum of Modern Art in Stockholm, Sweden _Suspects_: Unknown. _Method of Theft_: Smashed into the museum with a sledgehammer. _Status_: Recovered: 2013. Art Dealer Charles Roberts was offered the piece by an unknown Polish collector, after which he initiated a search on the Art Loss Register, discovering its status. He then worked with Art Loss to negotiate its return to the Swedish Ministry of Culture. _Worth_: $1 million

**2011**

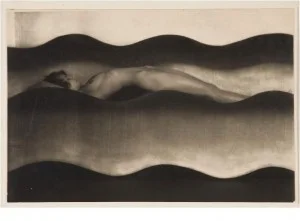

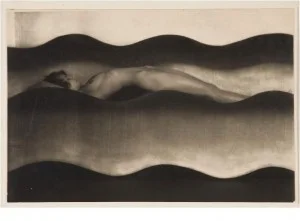

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487268508697-I0P4XGSEDVN7HOLV23VQ/wave.jpg)

“The Wave” František Drtikol The Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague, Czech Republic _Suspects_: Unknown. Allegedly a professional job. _Method of Theft:_ Walked through the front door, cut photograph from its frame. _Status_: Recovered: 2011. Police say the print was recovered when it was offered for sale at a gallery in California. The gallery owner, Joseph Bellows, contacted Art Loss, who informed police investigators. _Worth_: $1.25 million

**2012**

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487268458998-NL83BXHKR30O50M8HTFU/5.-Claude-Monet-Waterloo-Bridge.jpg)

“Waterloo Bridge” Claude Monet Kunsthal Museum in Rotterdam, Netherlands _Suspects_: Six Romanians, including Radu Dogaru, Alexandru Bitu, and Eugen Darie. _Method of Theft_: Unknown. Alarm sounded at 3 a.m. _Status_: Allegedly incinerated by Olga Dogaru, mother of one of the six accused. _Worth_: $24 million

**2005**

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487268461975-HWCWISGGQR9PWXEOOPYJ/8.-Looking-towards-Enkhuizen.jpg)

“View of Enkhuizen” Gerrit Pompe Westfries Museum in Hoorn, Netherlands _Suspects_: Unknown _Method of Theft_: Unclear. Thieves bypassed a recently inspected security alarm, leaving with 21 works in total. _Status_: Unrecovered. _Worth_: €10 Million

**2010**

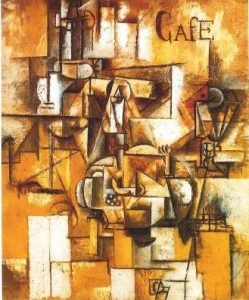

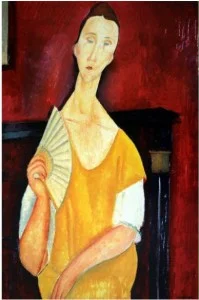

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487268455897-MOV6UJUW3UC2EKL0TT6X/3.-Picasso-Le-pigeon-aux-pois.jpg)[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487268458588-2PB88DUPOWTOTK35L2R2/4.-Modigliani-La-femme-a-leventail.jpg)

“Le Pigeon Aux Petit Pois” Pablo Picasso & “La Femme a L’eventail” Modigliani Museum of Modern Art in Paris, France _Suspects_: 43-year-old Serbian with the nickname “Spiderman;” a 34-year-old watch repairman, Jonathan B; and a 56-year-old antique shop owner. _Method of Theft_: Smashed window and padlock. Paintings carefully removed from their frames, rather than sliced out. A single masked intruder carried them away. _Status_: Unrecovered. _Worth_: Total of $123 million

**2011**

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487268468684-96TL6WH9O101I421PHK3/Barbara-Hepworth.jpg)

“Two Forms Divided Circles” Barbara Hepworth Dulwich Park in London, England _Suspects_: Unknown. _Method of Theft_: Hacked down with cutting tools, loaded it into a van. Allegedly melted down and sold as scrap metal. _Status_: Unrecovered. Worth: £500,000

**2012**

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487268487185-WIXQI8O88JZURAGGVCOM/Henry-Moore.jpg)

“Henry Moore” Sundial Henry Moore Foundation in Hertfordshire, England _Suspects_: Liam Hughes, 22, and Jason Parker, 19, both of Essex. _Method of Theft_: Lifted from the grounds of Henry Moore’s former home. _Status_: Recovered 2012. A metal dealer bought the piece for £46 pounds, and later saw it on Crimewatch. _Worth_: £500,000

**2013**

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487268459270-WXOB3X3ZWN6F6LBOBQQ5/6.-van-Dongen.jpg)

Kees Van Dongen “The Thinker” Van Buuren Museum near Brussels, Belgium _Suspects_: Unknown. _Method of Theft_: Broke in through a back door, pulled works from the wall, and escaped in a BMW in just over two minutes. _Status_: Unrecovered. Security at the museum has since been upgraded. _Worth_: €1 million

\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_

From the elusive Robert Wittman:

_There are supply countries and there are demand countries. The United States is a demand country. Western Europe, France, Switzerland, England, the U.S.—we’re demand countries. We’re the users. Peru, the Middle East; Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, and also Asian countries…usually the third world countries are the supply countries. That’s where it gets stolen from and it ends up here in collections._

There are countless examples of what Wittman so astutely points out here—the classical Greek Elgin Marbles displayed in the British Museum; the Eygpyt’s bust of Nefertiti at Berlin’s Egyptian Museum; the Etruscan Kalpis at the Toledo Museum of Art. For the latter, the water vessel was eventually returned to what is considered its rightful home, Italy. The work, as researched by the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, was illegally exported from its homeland. The museum acquired it from a Swiss art gallery in 1982, and it was formerly with a private collector. Instead of getting involved in a legal case, the museum returned it to the Italian Ministry of Culture. “It is part of our collections policy to deaccession and return any object for which we cannot provide clear title,” said museum director Brian Kennedy.

\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_

THE HOMEGROWN THIEF: ANOTHER FUCKING READYMADE

Written by Leland de la Durantaye

The difference between great artists and good ones is in how they steal. Certain of their independence, great artists know what they want, what they need, and they take it. Because the great artist is not concerned with being seen as a mere copyist, he or she can steal grandly and openly. Lesser artists cover their tracks, conceal the traces of their borrowing, and live in fear. This was a story often told in the first part of the 20th century, most famously by T. S. Eliot, who informed readers in 1921 that, “immature poets imitate, mature poets steal.” Eliot’s own work is full to bursting with things more or less maturely stolen: lines and images from Dante and Baudelaire, from Ovid and Shakespeare, from St. Augustine and _The Upanishads_. They are woven together: “fragments,” as the poet says at the end of _The Waste Land_, “shored against my ruins.”

But what about today’s fragments and their ruins? Various types of theft among artists in recent years have drummed up a discourse. One type is perfectly straightforward, and is seen in the current court case surrounding the alleged theft and sale of unfinished works by Jasper Johns by his longtime assistant. Another is less straightforward, and is exemplified in garbage—in the somewhat less recent court case concerning an individual who scavenged through Robert Rauschenberg’s trash, took certain items, and sold them as what they were (Robert Rauschenberg’s garbage). A more complex form of theft is that of Maurizio Cattelan who, in 1997, broke into the Galerie Bloom in Amsterdam, stole its entire collection, and put it up the next day in a nearby Amsterdam gallery with the title, Another Fucking Readymade. (The police arrived not long after.)

In Cattelan’s act of theft, the parading of the crime and the treating of someone else’s work as though it were as anonymous and readymade as a urinal or a bottle holder was part of the spectacle. One thing this demonstrates is that while legal definitions of theft may be clear enough for present purposes, _artistic_ definitions of theft are far from clear.

We can find a response, if not quite an answer, in Cattelan’s own remarks. “I’m not trying to be against institutions or museums,” he remarked in an interview with Nancy Spector for the book _Maurizio Cattelan: All_. “Maybe I’m just saying that we are all corrupted in a way; life itself is corrupted, and that’s the way we like it.”

Independent of our level of corruption, and of how much we like it, is the question of what artists—visual and verbal—take from one another. Where does influence stop and theft start? Maybe Eliot was wrong, not in distinguishing major artists from minor ones in function of how they deal with the anxiety of influence, but in calling one mode _theft_. Maybe art is too flexible a field to admit of theft—even in such a radical case as Cattelan’s. You can of course steal Rembrandt’s “The Storm on the Sea of Galilee,” but can you steal its motifs, its coloring, its upsweeping waves or its calm demeanor? They are there for the taking. They are, as Eliot’s friend Ezra Pound once said, “thy true heritage.” Do with them what you will.

Rembrandt van Rijn. “The Storm on the Sea of Galilee.” (1633). 161.7 x 129.8 cm. Oil on canvas. Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Courtesy The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.

Aerial view Los Angeles County Museum of Art. (c. 1965). William L. Pereira and Associates, architects. Photo © 2013 Museum Associates/LACMA, photographic archives.

Jan Vermeer. “The Concert.” (1658–1660) 72.5 x 64.7 centimeters. Oil on canvas.

Courtesy The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.

The Painter of Vatican 238. “Kalpis (Water Vessel) with Pirates Transforming into Dolphins,” (520‑510 BCE). Courtesy the Toledo Museum of Art.

Maurizio Cattelan. “Another Fucking Readymade,” (1996). Crated and wrapped gallery contents. Variable dimensions. Courtesy Maurizio Cattelan’s Archive.

[](#)[](#)

The Heist, The Larcenist, The Van Goyen, The Purloined

The Thief & His Guide How To Steal From LACMA

The criminality of theft has been tempered by literary romanticism of the thief since Prometheus’ theft of fire enabled progress within civilization.

Why do we glorify the larcenist? Is it the thrill in a world of “no”s to discover that nearly everything is obtainable? The heroic outlaw running gallantly through the forest, rakish feather in cap, aiding the poor with the unauthorized loot of the rich lends a sense of justice to our cold universe. And the art thief is held in even higher esteem; always near-genius, and often casually speeding off in “one of those red Italian things.”

In truth, the motivations for these crimes, committed by these criminals, often only serve to perplex. Kids steal sculpture for scrap metal; war-torn countries face nihilistic looters; a lowly assistant quietly swipes a painting from his mentor.

In the face of these nonlinear events we present: a few thoughts on art theft.

I wish I could tell you that the best way to steal art from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art would involve some hi-tech gadgetry and ingenious, Thomas Crownian sleight-of-hand. Sure, you could slip into the security control room disguised as a custodian and attach a scrambler to the CCTV to send the video into continuous loop. You could hack into the computer system to cut off electricity to the room in question, and have your accomplice lift the painting off the wall (in case you were wondering, I’d swipe Magritte’s “The Treachery of Images,” take it home, and stage secret discussions of Foucault’s interpretation of it, while serving tapas and smoking shisha from a water pipe). You’d pop it out of its frame and make a break for the door, just as another associate pulls the fire alarm. Such a plan just might work, and it’s the more cinematic approach.

But the popular perception of art theft is stuck back in the Victorian era, when loan dexterous thieves with non-violent, gentlemanly aspirations stole art for reasons more ideological than financial. The reality is that, since the Second World War, the majority of art crime has been perpetrated by, or on behalf of, organized crime groups. For decades, art crime has been the third-highest-grossing criminal trade worldwide, behind only drugs and arms. It even funds terrorism, with Mohammed Atta, of the 9/11 attacks, known to have sought buyers for looted Afghani antiquities, profits from which he was planning to use to buy a plane to crash into buildings. In art theft, it is often not just the art that is at stake.

All these uncomfortable truths about art theft mean that art is most effectively stolen via the blunt instrument approach—what I call a “blitz theft.” It is the mark of organized crime’s involvement in a heist, and may be seen from the Munch Museum to the Bührle Collection, from the National Gallery of Sweden to the Museum of Eastern and Western Art of Odessa. In each incident, armed and masked assailants wielding automatic firearms burst into the museum during opening hours. They shouted the shocked visitors and guards to the floor, ripped a few artworks off the walls, and made a swift exit. What of the million-dollar alarm systems, you ask? Oh sure, they went off. But average police response time in cities is three to five minutes, and that’s on a good day. So if the thieves got out in less than three minutes, the alarms didn’t matter. They were simply expensive noise boxes. By the time help arrived, the thieves were long gone, sometimes in dramatic fashion. At the National Gallery of Sweden, they got away via a speedboat that awaited them in the bay behind the museum.

By night, museums can lock themselves down like bank vaults. Precious few thieves are skillful, or foolish, enough to steal from museums when they’re closed. But during open hours, these museums must give the public as comfortable access as possible to their collections, while still keeping them safe—a tough balancing act. Only stoppable by clogging up the entrance to museums with airport-style security, blitz thefts represent the greatest and most difficult threat. Security guards are not expected to engage in firefights with burglars, nor should they turn a theft into a potential gun battle or hostage situation. Art thefts are rare enough that most museums are never threatened by them, so it’s natural that security guards might “switch off” after a decade-long career without a single real incident. Organized criminals know this, and thus turn to smash-and-grab techniques, while the world expects art thieves to slink around in leather bodysuits, dodging lasers and dangling upside-down from skylights. The scary art thieves are the armed gangsters, who aim to turn stolen art into drugs and arms, illicit art funding the more sinister activities of criminal gangs and syndicates. The scariest of all are those who loot antiquities, tear out the treasures of the earth, and sell them to fund terrorist attacks.

LACMA should keep its Magritte. But let the museum be warned—all the alarms in the world won’t protect against blitz thefts. When the defenders expect the barbarians to come in stealth by night, the cleverest barbarians barge straight in through the front door.

\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_

From the illustrious Robert Wittman, former FBI agent who specialized in art theft cases and aided in the recovery of $300 million worth of stolen art:

_In the \[Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum Heist\] in 1990, they took a number of paintings that were actually in their frames and a couple that were on a stretcher. They actually cut out a couple very big Rembrandts and they rolled those up. Usually when we see people cutting paintings out of frames and rolling them, we know that they’re not professionals because that’s the quickest way to destroy a painting._

During the March 18th 1990 heist at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, two men dressed as police officers infiltrated the closed museum, bound the two on duty security guards, and made off with 13 works worth $500 million. “The Concert,” one of 36 known Vermeer’s in existence, was included in the loot and has yet to resurface in the public market, likely due to the high-status of the theft and its characteristic mark of a stolen image: being cut from the frame.

Artist Sophie Calle, alludes to this aspect of the theft in her most recent exhibition, “Last Seen” currently on view at the Gardner Museum (October 24, 2013–March 3, 2014). In the exhibit of photographs, anonymous viewers confront the butchering, looking to the empty frames still hung on the walls.

All 13 works remain unrecovered.

\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_

THE PAINTING, THE THIEF, THE ARTIST, THE MUSEUM, & THEIR LEGENDS: FOUR MAJOR WORKS OF LOSS

Fiction by Andrew Stark History by Chinnie Ding

THE PAINTING: REMBRANDT VAN RIJN’S “DANAË”

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487268485002-1QJBVIBN7ARBFZVVWMNG/GE_723.jpg)

_There exists no vocabulary for certain events, no words strong enough. Language gets reduced to something primitive, monosyllabic and untranslatable, the animal babble of intense lament. When the man appeared and flashed his blade, that gristled Lithuanian with eyes like stones, the crowd surrounding us became one homogenized embranglement of frenzy and fear. They communicated their panic through a series of yelps, slanting to the gallery floor. The man slashed my stomach and my thigh as if I were a lover who’d slighted him, some vile propinquity. There was passion in his redbrick face. Then, in a flourish, he pulled from his coat a bottle of sulfuric acid and crossed it over my eight-by-ten expanse in deranged anointment. Guards wrestled him to his knees, a strange gesture of supplication. Everyone, as they say, was speechless._

_That very same day, the restoration process began by a number of people from the State Hermitage’s Laboratory of Expert Restoration of Easel Paintings. They consulted with chemists about my face, settled debates regarding the scientific methodology of my right arm. After twelve years, they said, I was complete. But something had been lost—the essence of my creator’s original devotion—and I became nothing more than a tourist attraction. It doesn’t matter, I suppose, because even the most memorable lives are forgotten._

Acquired in 1772 by Catherine the Great herself for the Hermitage’s founding collection, Rembrandt van Rijn’s “Danaë” presents an image we shouldn’t be privy to. Pent up in a tower by her father to keep her chaste, the Greek princess of legend rises from her bed in anticipation as Zeus, in the form of a golden haze, enters the chamber to have his way. Her life-size, soft-edged body, flushed cheeks, and ambiguous expression capture that stirring, secret moment when untouched desire becomes vulnerably visible—and potentially receptive. Although the semi-reclining female nude was already becoming a favored trope—see the Venuses of Giorgione, Titian, Velasquez, and iconic successors like Ingres’s “Odalique” and Manet’s “Olympia”—it was still a brave subject for the Dutch painting of Rembrandt’s time. Something about the heady naturalism of “Danaë” embarrassed several generations of Russian aristocracy, too, who periodically stowed it away from view.

In 1985, then, when a Lithuanian man named Bronius Maigis razor-slashed, then acid-splashed the canvas center, rookie psychoanalysts might have called out vicarious sexual violence. Yet Maigis himself declared it an act of political protest: He’d chosen the very day that, in 1940, Lithuania lost its independence to the USSR. All the more reason, perhaps, that the uncompromising Kremlin vetoed pessimistic museum experts to demand restoration straightaway (while censoring Maigis’s motives and shipping him to an asylum). Aided by an obscure 19th-century copy and a balm of honey and sturgeon glue, conservators would take the next 12 years to reconstruct the original’s sly and glorious provocation.

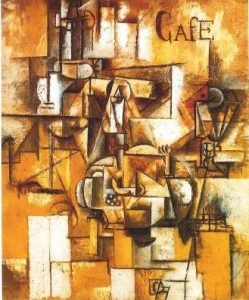

THE THIEF: PABLO PICASSO’S “LE PIGEON AUX PETIT POIS”

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487268457971-8IMRHI19OTAOFSBDC66R/3.-Picasso-Le-pigeon-aux-pois1.jpg)

_Cunts. I slipped into the Musée d’Art Moderne after lights out like I’d been invited. Because I fucking could, that’s why. It was genius. Place had a faulty alarm system and three sleeping guards. I planned for months. Swiped a Picasso, a Matisse and a few more—about €100 million worth. I’m a criminal satisfying a criminal thrill. I’m menacing, skulking, the coyote who haunts your farm. I’d just as soon massage my knife into your throat to get my pulse going. Because conscience is just a bullshit weakness that hums under the skin. It swims in your blood like red tide, crowding the coward’s heart. You think you know me—some skinny kid growing up in the projects, the cmpaћapa, putting myself to bed hungry as cries echo from my belly like frogs in the dark. Yeah, you think you know. I’m just like you, but I’ve got balls. When God calls time-out and we all quit playing, when the bombs drop and the stores are looted clean and every last generator chugs to an asthmatic halt, I’ll torch these so-called masterpieces just to keep my fucking tootsies warm._

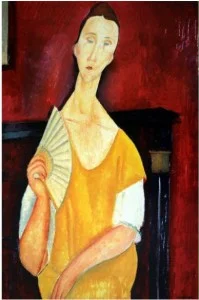

Pablo Picasso takes the prize for most pilfered artist in recorded history: to date, nearly 1,200 of his works have been reported missing by the Art Loss Register, and that’s not counting those believed to have perished in a 1943 Nazi bonfire of “degenerate art.” “Le Pigeon aux Petit Pois,” painted in 1911, was a seminal work of the cubist avant-garde movement. The work was taken by a single, stealthy thief in the spring of 2010 from the Musée d’Art Moderne. In terms of value, it’s one of the biggest heists of our time, as the thief also managed to swipe Henri Matisse’s “La Pastorale,” Amedeo Modigliani’s “La Femme à l’éventail,” Georges Braque’s “ L’Olivier Près de l’Estaque,” and Fernand Léger’s “Nature Morte aux Chandeliers.” Combined, the estimated value is $123 million, and the identity of the thief remains unknown.

The cubist work of “Le Pigeon aux Petit Pois” was a gradual continuation from Picasso’s earlier proto-cubist paintings, such as his highly regarded “Le Demoiselles d’Avignon,” characterized by the work’s disjointed shapes. Picasso was one of the pioneers of the movement (one that included Georges Braque and Fernand Leger) that was originally coined by critics as an insult. Picasso’s departure from cubism led to paintings noteworthy for bolder colors, bringing to mind another of his famous works, “Woman’s Head” that was stolen in early 2012. Painted in 1939, it was given by Picasso himself to the people of Greece in 1949, honoring their wartime resistance. The timing of its theft from the National Gallery in Athens was historic, too, in an unhappier way: Greece in early 2012 was in the throes of austerity, and museum security happened to be on a three-day strike. The lone guard on duty was a temp, blindsided by the professional seven-minute snatch.

THE ARTIST: KAREL APPEL’S “PHANTASMAGORIA NO. 162.”

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487268497574-QESE6Y6TOBUN80S0YDIG/Phantasmagoria-No.162-by-Karel-Appel.jpg-by-Karel-Appel.jpg?format=original)

_I wake each morning to a different view. Sometimes a snowcapped mountain speckled with goats, other times a city street. Or paisley patterns of rain hanging over a field, farmhouses flickering out there in the gloom like sparse constellations. Being in Heaven, it’s like changing the channel. I could be playing pinochle in my childhood home of Dapperstraat 7 one day, or munching spiced beluga lentils and niçoise toasts at some ten-acre chateau the next. Yesterday, for example, I took my coffee at the Rebel 74 on US 95. I’m usually young and healthy, lounging in a sunlit park. But I like to be old, too, hit with aches and spells and all the unpredictable flexures of the heart that make me feel human again._

_I hear things, of course, but I generally don’t pay attention to the news down there. Some of my work “went missing” years ago and was then recovered. It was a big deal, for some. I just watch my wife, Harriet, if I watch at all. Harriet wearing a trumpet gown of Alençon lace at some benefit, Harriet laying flowers on my grave at Cimetière du Père-Lachaise. Harriet smiling. But the days lose momentum._

_Sometimes, when I’m feeling particularly lonely, I surround myself with nothing, occupying a shapeless void, and I can hear the froth of distant oceans, the hiss of distant stars. I become suddenly aware of eternity’s drag, like we’re all floating around some atmospheric vacuum, surrounded by dark energy, without destination or purpose, propelled by nothing but the currents of space and the memory of time._

While it’s nice to think that art belongs to none and all, many of the world’s finest artworks are decisively hidden from public view, whether secreted in private collections or backlisted in museum depositories. As the art market’s big spenders are increasingly investors—who buy to hold then sell—the storage of art has itself become a booming industry, with an entire apparatus of free ports and logistics firms in tow. Those warehouses and shipping containers can hide illicit art traffic, too, as seen in the 2002 disappearance in transit of some 400 works by Karel Appel, shipped by the Dutch artist to his Amsterdam foundation. When that missing crate turned up nine years later at a London auction house, after Appel’s death, it was being consigned by a transport and storage company that supposedly discovered the works in a newly acquired facility.

A prolific postwar Expressionist, Appel co-founded CoBrA, an avant-garde movement (named for its founders’ hometowns: Copenhagen, Brussels, Amsterdam) that idealized boldly instinctive, childlike image-making as the basis for a radical folk art of the future. Blasts of color give his paintings a joyfully naïve, spastic quality—think Jean Dubuffet or Joan Miro on a sugar high—and his gooey, gleeful blotches often evoke boogeymen or impish imaginary friends. The lost and found “Phantasmagoria No. 162” shows Appel superimposing a print with acrylic paint and oil stick in fast, coiling scribbles—its frenetic, ghostly goblin like some spirit-animal of the artist himself, posthumously unleashed.

THE MUSEUM: “VICTORIOUS YOUTH”

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487268522800-98RIUL924FJUXZJRGRY9/Victorious-Youth.jpg)

_I am the J. Paul Getty Museum, and I adore every work of art enshrined within me. I wear them—the illusionistic portraits, those eighteenth-century French commodes, all the travelling exhibitions passing through on their Möbius trajectory from one gallery to the next—like wartime talismans, battlefield charms, something clipped to the helmet or stored near the heart. They are my children, my babies. But none compare, really, to my centerpiece, The Getty Bronze._

_He’s endured a lot, this one, like a child fed through the meat grinder of foster care. In the summer of 1964, an Italian trawler pulled up its nets about 32 miles off the coast of Fano, only to find they’d fetched my boy from the syrupy sea. The fishermen elected to sell him, which drummed up more than a little controversy. The Getty Bronze was then hidden in a bathtub, a cabbage field, beneath the wooden staircase of a local church. In 1977, a year after the death of my father, Jean Paul, the Getty acquired its Bronze and we were united. But, since a number of esoteric regulations had been breached since my boy’s discovery, Italy is attempting to secure his repatriation through some kind of transnational forfeiture action. The custody battle fuels my loss, devastation. If I knew words anchoring more weight, I would surely use them._

_I love my visitors, all my guests. The stately old woman whose curlicued up-do looks like it was styled with an ice cream scoop, the burly Midwesterner escaping the deep-fried riot of suburban redundancy, the donnish Manhattan critic who carries herself like an exclamation point and fills my rooms like a wolf whistle. But my favorites are the ones who stop and stare, really look, and I can see something register in their faces, the meditative turning of a psychological key, and I know they are seeing something inside themselves, navigating the lyrical web of dead memory. In this way my children speak to them._

L.A.’s sun- and fund-drenched Getty Museum is no stranger to scandal. In the past few decades, the art acropolis of the West Coast has been accused of tax fraud and sexual discrimination, fabricating paper trails and hushing up forgeries. The museum’s most heated controversy of late has focused on the “Victorious Youth,” a.k.a. the Getty Bronze, a virtuosic life-size bronze sculpture from the early Hellenistic period, which Italian authorities say amounts to a smuggled artifact. Nevermind that the statue was first recovered in 1964 by fishermen in the international waters of the Adriatic Sea. Or the other historical irony that, before sinking in a first-century Roman shipwreck, the statue was probably being looted out of Greece to satisfy the Grecomania of Roman collectors.

Surviving Greek bronzes are rare—most were melted down for metal—and all the rarer are those connected to the legendary Lysippos, Alexander the Great’s anointed court sculptor. Traditionally attributed to Lysippos or a gifted student, this Victorious Youth crowning himself with a laurel wreath after an athletic victory, stands rather svelte and relaxed in his confirmed triumph. It both constitutes a trophy and depicts a trophy moment.

Since 2005, amid a larger battle waged in the Italian high courts, newspaper screeds, cultural embargo threats, institutional scapegoating, and dramatic police raids on suspect dealers’ stashes across Europe—which produced damning evidence of the Getty’s fast-and-loose antiquities acquisitions—the museum has returned 49 artifacts to Italy. It refuses to give up the Getty Bronze, however, arguing it cannot repatriate what Italy never owned. While just last year an Italian court upped the ante by authorizing seizure, it’s not clear whether U.S. authorities will enforce the order. For now, the youth continues to gaze out from the Getty Villa in Malibu, insouciant to all this strife.

\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_

A BRIEF CHRONOLOGY OF LUNACY & GENIUS

Acts of creation are often linked to the celestial. The Madonna was merely a vessel for divinity. Similarly, as popular rhetoric goes, artists are merely a vessel for their own creations. And yet, the stealing of that work offers a broader placement for responsibility. Acts of theft (and the destruction attached to those acts) are mere feats of ethnologic will. In art pillaging anyone can take a try—from a sloppy teenager in the marshlands of Britain to an Eastern European cat burglar. One need not know how to paint “Poppy Flowers” by Vincent van Gogh to take a knife to its visage and free it from its frame. The gap in technique, then, is often staggering. Art Loss Register, the largest private database of stolen art in the world, documents these thefts, while aiding in the research and return of the work. Here, Art Loss Chairman Julian Radcliffe curates a list of heists—executed with lunacy, pratfalls, and puzzling moments of genius—that piqued his interest.

**1941**

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487268474599-GUWCHONAUMYF52XJP4EJ/Dr-Peter-Turner-Bust.jpg)

“Dr. Peter Turner” Mediaeval Church of St. Olave Hart Street in London, England _Suspects_: Unknown. _Method of Theft_: Walked through rubble, pulled the bust from its damaged nave after bombings by the German Luftwaffe during the London Blitz. _Status_: Recovered; 2011. Curator at the Museum of London got wind of its impending auction, tipped off church officials. Art Loss took on the case and the alabaster bust was withdrawn from the sale. _Worth_: £70,000

**1979**

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487268455097-I7UHAUD78LXU1XQRXCVZ/2.-Claesz-Still-life.jpg)

“Still Life” Pieter Claesz Private Residence of Paul Mitchell in London, England _Suspects_: Unknown. _Method of Theft_: Forced open a window, left with 10 works total. Mitchell assumed the noise was the family cat. _Status_: Unrecovered. One painting did resurface from this theft; Art Loss lawyer Christopher Marinello recovered the van Goyen. _Worth_: Combined Artwork; £1 Million

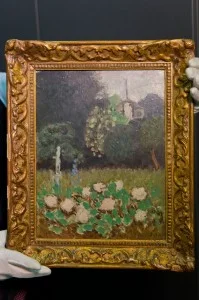

**1987**

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487268491266-V3YXHT77L5CD3TOTGL2S/Matisse.jpg)

“Le Jardin” Henri Matisse Museum of Modern Art in Stockholm, Sweden _Suspects_: Unknown. _Method of Theft_: Smashed into the museum with a sledgehammer. _Status_: Recovered: 2013. Art Dealer Charles Roberts was offered the piece by an unknown Polish collector, after which he initiated a search on the Art Loss Register, discovering its status. He then worked with Art Loss to negotiate its return to the Swedish Ministry of Culture. _Worth_: $1 million

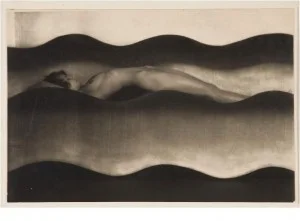

**2011**

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487268508697-I0P4XGSEDVN7HOLV23VQ/wave.jpg)

“The Wave” František Drtikol The Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague, Czech Republic _Suspects_: Unknown. Allegedly a professional job. _Method of Theft:_ Walked through the front door, cut photograph from its frame. _Status_: Recovered: 2011. Police say the print was recovered when it was offered for sale at a gallery in California. The gallery owner, Joseph Bellows, contacted Art Loss, who informed police investigators. _Worth_: $1.25 million

**2012**

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487268458998-NL83BXHKR30O50M8HTFU/5.-Claude-Monet-Waterloo-Bridge.jpg)

“Waterloo Bridge” Claude Monet Kunsthal Museum in Rotterdam, Netherlands _Suspects_: Six Romanians, including Radu Dogaru, Alexandru Bitu, and Eugen Darie. _Method of Theft_: Unknown. Alarm sounded at 3 a.m. _Status_: Allegedly incinerated by Olga Dogaru, mother of one of the six accused. _Worth_: $24 million

**2005**

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487268461975-HWCWISGGQR9PWXEOOPYJ/8.-Looking-towards-Enkhuizen.jpg)

“View of Enkhuizen” Gerrit Pompe Westfries Museum in Hoorn, Netherlands _Suspects_: Unknown _Method of Theft_: Unclear. Thieves bypassed a recently inspected security alarm, leaving with 21 works in total. _Status_: Unrecovered. _Worth_: €10 Million

**2010**

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487268455897-MOV6UJUW3UC2EKL0TT6X/3.-Picasso-Le-pigeon-aux-pois.jpg)[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487268458588-2PB88DUPOWTOTK35L2R2/4.-Modigliani-La-femme-a-leventail.jpg)

“Le Pigeon Aux Petit Pois” Pablo Picasso & “La Femme a L’eventail” Modigliani Museum of Modern Art in Paris, France _Suspects_: 43-year-old Serbian with the nickname “Spiderman;” a 34-year-old watch repairman, Jonathan B; and a 56-year-old antique shop owner. _Method of Theft_: Smashed window and padlock. Paintings carefully removed from their frames, rather than sliced out. A single masked intruder carried them away. _Status_: Unrecovered. _Worth_: Total of $123 million

**2011**

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487268468684-96TL6WH9O101I421PHK3/Barbara-Hepworth.jpg)

“Two Forms Divided Circles” Barbara Hepworth Dulwich Park in London, England _Suspects_: Unknown. _Method of Theft_: Hacked down with cutting tools, loaded it into a van. Allegedly melted down and sold as scrap metal. _Status_: Unrecovered. Worth: £500,000

**2012**

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487268487185-WIXQI8O88JZURAGGVCOM/Henry-Moore.jpg)

“Henry Moore” Sundial Henry Moore Foundation in Hertfordshire, England _Suspects_: Liam Hughes, 22, and Jason Parker, 19, both of Essex. _Method of Theft_: Lifted from the grounds of Henry Moore’s former home. _Status_: Recovered 2012. A metal dealer bought the piece for £46 pounds, and later saw it on Crimewatch. _Worth_: £500,000

**2013**

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487268459270-WXOB3X3ZWN6F6LBOBQQ5/6.-van-Dongen.jpg)

Kees Van Dongen “The Thinker” Van Buuren Museum near Brussels, Belgium _Suspects_: Unknown. _Method of Theft_: Broke in through a back door, pulled works from the wall, and escaped in a BMW in just over two minutes. _Status_: Unrecovered. Security at the museum has since been upgraded. _Worth_: €1 million

\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_

From the elusive Robert Wittman:

_There are supply countries and there are demand countries. The United States is a demand country. Western Europe, France, Switzerland, England, the U.S.—we’re demand countries. We’re the users. Peru, the Middle East; Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, and also Asian countries…usually the third world countries are the supply countries. That’s where it gets stolen from and it ends up here in collections._

There are countless examples of what Wittman so astutely points out here—the classical Greek Elgin Marbles displayed in the British Museum; the Eygpyt’s bust of Nefertiti at Berlin’s Egyptian Museum; the Etruscan Kalpis at the Toledo Museum of Art. For the latter, the water vessel was eventually returned to what is considered its rightful home, Italy. The work, as researched by the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, was illegally exported from its homeland. The museum acquired it from a Swiss art gallery in 1982, and it was formerly with a private collector. Instead of getting involved in a legal case, the museum returned it to the Italian Ministry of Culture. “It is part of our collections policy to deaccession and return any object for which we cannot provide clear title,” said museum director Brian Kennedy.

\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_

THE HOMEGROWN THIEF: ANOTHER FUCKING READYMADE

Written by Leland de la Durantaye

The difference between great artists and good ones is in how they steal. Certain of their independence, great artists know what they want, what they need, and they take it. Because the great artist is not concerned with being seen as a mere copyist, he or she can steal grandly and openly. Lesser artists cover their tracks, conceal the traces of their borrowing, and live in fear. This was a story often told in the first part of the 20th century, most famously by T. S. Eliot, who informed readers in 1921 that, “immature poets imitate, mature poets steal.” Eliot’s own work is full to bursting with things more or less maturely stolen: lines and images from Dante and Baudelaire, from Ovid and Shakespeare, from St. Augustine and _The Upanishads_. They are woven together: “fragments,” as the poet says at the end of _The Waste Land_, “shored against my ruins.”

But what about today’s fragments and their ruins? Various types of theft among artists in recent years have drummed up a discourse. One type is perfectly straightforward, and is seen in the current court case surrounding the alleged theft and sale of unfinished works by Jasper Johns by his longtime assistant. Another is less straightforward, and is exemplified in garbage—in the somewhat less recent court case concerning an individual who scavenged through Robert Rauschenberg’s trash, took certain items, and sold them as what they were (Robert Rauschenberg’s garbage). A more complex form of theft is that of Maurizio Cattelan who, in 1997, broke into the Galerie Bloom in Amsterdam, stole its entire collection, and put it up the next day in a nearby Amsterdam gallery with the title, Another Fucking Readymade. (The police arrived not long after.)

In Cattelan’s act of theft, the parading of the crime and the treating of someone else’s work as though it were as anonymous and readymade as a urinal or a bottle holder was part of the spectacle. One thing this demonstrates is that while legal definitions of theft may be clear enough for present purposes, _artistic_ definitions of theft are far from clear.

We can find a response, if not quite an answer, in Cattelan’s own remarks. “I’m not trying to be against institutions or museums,” he remarked in an interview with Nancy Spector for the book _Maurizio Cattelan: All_. “Maybe I’m just saying that we are all corrupted in a way; life itself is corrupted, and that’s the way we like it.”

Independent of our level of corruption, and of how much we like it, is the question of what artists—visual and verbal—take from one another. Where does influence stop and theft start? Maybe Eliot was wrong, not in distinguishing major artists from minor ones in function of how they deal with the anxiety of influence, but in calling one mode _theft_. Maybe art is too flexible a field to admit of theft—even in such a radical case as Cattelan’s. You can of course steal Rembrandt’s “The Storm on the Sea of Galilee,” but can you steal its motifs, its coloring, its upsweeping waves or its calm demeanor? They are there for the taking. They are, as Eliot’s friend Ezra Pound once said, “thy true heritage.” Do with them what you will.

Rembrandt van Rijn. “The Storm on the Sea of Galilee.” (1633). 161.7 x 129.8 cm. Oil on canvas. Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Courtesy The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.

Aerial view Los Angeles County Museum of Art. (c. 1965). William L. Pereira and Associates, architects. Photo © 2013 Museum Associates/LACMA, photographic archives.

Jan Vermeer. “The Concert.” (1658–1660) 72.5 x 64.7 centimeters. Oil on canvas.

Courtesy The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.

The Painter of Vatican 238. “Kalpis (Water Vessel) with Pirates Transforming into Dolphins,” (520‑510 BCE). Courtesy the Toledo Museum of Art.

Maurizio Cattelan. “Another Fucking Readymade,” (1996). Crated and wrapped gallery contents. Variable dimensions. Courtesy Maurizio Cattelan’s Archive.

[](#)[](#)

The Heist, The Larcenist, The Van Goyen, The Purloined

The Thief & His Guide How To Steal From LACMA

The criminality of theft has been tempered by literary romanticism of the thief since Prometheus’ theft of fire enabled progress within civilization.

Why do we glorify the larcenist? Is it the thrill in a world of “no”s to discover that nearly everything is obtainable? The heroic outlaw running gallantly through the forest, rakish feather in cap, aiding the poor with the unauthorized loot of the rich lends a sense of justice to our cold universe. And the art thief is held in even higher esteem; always near-genius, and often casually speeding off in “one of those red Italian things.”

In truth, the motivations for these crimes, committed by these criminals, often only serve to perplex. Kids steal sculpture for scrap metal; war-torn countries face nihilistic looters; a lowly assistant quietly swipes a painting from his mentor.

In the face of these nonlinear events we present: a few thoughts on art theft.

I wish I could tell you that the best way to steal art from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art would involve some hi-tech gadgetry and ingenious, Thomas Crownian sleight-of-hand. Sure, you could slip into the security control room disguised as a custodian and attach a scrambler to the CCTV to send the video into continuous loop. You could hack into the computer system to cut off electricity to the room in question, and have your accomplice lift the painting off the wall (in case you were wondering, I’d swipe Magritte’s “The Treachery of Images,” take it home, and stage secret discussions of Foucault’s interpretation of it, while serving tapas and smoking shisha from a water pipe). You’d pop it out of its frame and make a break for the door, just as another associate pulls the fire alarm. Such a plan just might work, and it’s the more cinematic approach.

But the popular perception of art theft is stuck back in the Victorian era, when loan dexterous thieves with non-violent, gentlemanly aspirations stole art for reasons more ideological than financial. The reality is that, since the Second World War, the majority of art crime has been perpetrated by, or on behalf of, organized crime groups. For decades, art crime has been the third-highest-grossing criminal trade worldwide, behind only drugs and arms. It even funds terrorism, with Mohammed Atta, of the 9/11 attacks, known to have sought buyers for looted Afghani antiquities, profits from which he was planning to use to buy a plane to crash into buildings. In art theft, it is often not just the art that is at stake.

All these uncomfortable truths about art theft mean that art is most effectively stolen via the blunt instrument approach—what I call a “blitz theft.” It is the mark of organized crime’s involvement in a heist, and may be seen from the Munch Museum to the Bührle Collection, from the National Gallery of Sweden to the Museum of Eastern and Western Art of Odessa. In each incident, armed and masked assailants wielding automatic firearms burst into the museum during opening hours. They shouted the shocked visitors and guards to the floor, ripped a few artworks off the walls, and made a swift exit. What of the million-dollar alarm systems, you ask? Oh sure, they went off. But average police response time in cities is three to five minutes, and that’s on a good day. So if the thieves got out in less than three minutes, the alarms didn’t matter. They were simply expensive noise boxes. By the time help arrived, the thieves were long gone, sometimes in dramatic fashion. At the National Gallery of Sweden, they got away via a speedboat that awaited them in the bay behind the museum.

By night, museums can lock themselves down like bank vaults. Precious few thieves are skillful, or foolish, enough to steal from museums when they’re closed. But during open hours, these museums must give the public as comfortable access as possible to their collections, while still keeping them safe—a tough balancing act. Only stoppable by clogging up the entrance to museums with airport-style security, blitz thefts represent the greatest and most difficult threat. Security guards are not expected to engage in firefights with burglars, nor should they turn a theft into a potential gun battle or hostage situation. Art thefts are rare enough that most museums are never threatened by them, so it’s natural that security guards might “switch off” after a decade-long career without a single real incident. Organized criminals know this, and thus turn to smash-and-grab techniques, while the world expects art thieves to slink around in leather bodysuits, dodging lasers and dangling upside-down from skylights. The scary art thieves are the armed gangsters, who aim to turn stolen art into drugs and arms, illicit art funding the more sinister activities of criminal gangs and syndicates. The scariest of all are those who loot antiquities, tear out the treasures of the earth, and sell them to fund terrorist attacks.

LACMA should keep its Magritte. But let the museum be warned—all the alarms in the world won’t protect against blitz thefts. When the defenders expect the barbarians to come in stealth by night, the cleverest barbarians barge straight in through the front door.

\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_

From the illustrious Robert Wittman, former FBI agent who specialized in art theft cases and aided in the recovery of $300 million worth of stolen art:

_In the \[Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum Heist\] in 1990, they took a number of paintings that were actually in their frames and a couple that were on a stretcher. They actually cut out a couple very big Rembrandts and they rolled those up. Usually when we see people cutting paintings out of frames and rolling them, we know that they’re not professionals because that’s the quickest way to destroy a painting._

During the March 18th 1990 heist at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, two men dressed as police officers infiltrated the closed museum, bound the two on duty security guards, and made off with 13 works worth $500 million. “The Concert,” one of 36 known Vermeer’s in existence, was included in the loot and has yet to resurface in the public market, likely due to the high-status of the theft and its characteristic mark of a stolen image: being cut from the frame.

Artist Sophie Calle, alludes to this aspect of the theft in her most recent exhibition, “Last Seen” currently on view at the Gardner Museum (October 24, 2013–March 3, 2014). In the exhibit of photographs, anonymous viewers confront the butchering, looking to the empty frames still hung on the walls.

All 13 works remain unrecovered.

\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_

THE PAINTING, THE THIEF, THE ARTIST, THE MUSEUM, & THEIR LEGENDS: FOUR MAJOR WORKS OF LOSS

Fiction by Andrew Stark History by Chinnie Ding

THE PAINTING: REMBRANDT VAN RIJN’S “DANAË”

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487268485002-1QJBVIBN7ARBFZVVWMNG/GE_723.jpg)

_There exists no vocabulary for certain events, no words strong enough. Language gets reduced to something primitive, monosyllabic and untranslatable, the animal babble of intense lament. When the man appeared and flashed his blade, that gristled Lithuanian with eyes like stones, the crowd surrounding us became one homogenized embranglement of frenzy and fear. They communicated their panic through a series of yelps, slanting to the gallery floor. The man slashed my stomach and my thigh as if I were a lover who’d slighted him, some vile propinquity. There was passion in his redbrick face. Then, in a flourish, he pulled from his coat a bottle of sulfuric acid and crossed it over my eight-by-ten expanse in deranged anointment. Guards wrestled him to his knees, a strange gesture of supplication. Everyone, as they say, was speechless._

_That very same day, the restoration process began by a number of people from the State Hermitage’s Laboratory of Expert Restoration of Easel Paintings. They consulted with chemists about my face, settled debates regarding the scientific methodology of my right arm. After twelve years, they said, I was complete. But something had been lost—the essence of my creator’s original devotion—and I became nothing more than a tourist attraction. It doesn’t matter, I suppose, because even the most memorable lives are forgotten._

Acquired in 1772 by Catherine the Great herself for the Hermitage’s founding collection, Rembrandt van Rijn’s “Danaë” presents an image we shouldn’t be privy to. Pent up in a tower by her father to keep her chaste, the Greek princess of legend rises from her bed in anticipation as Zeus, in the form of a golden haze, enters the chamber to have his way. Her life-size, soft-edged body, flushed cheeks, and ambiguous expression capture that stirring, secret moment when untouched desire becomes vulnerably visible—and potentially receptive. Although the semi-reclining female nude was already becoming a favored trope—see the Venuses of Giorgione, Titian, Velasquez, and iconic successors like Ingres’s “Odalique” and Manet’s “Olympia”—it was still a brave subject for the Dutch painting of Rembrandt’s time. Something about the heady naturalism of “Danaë” embarrassed several generations of Russian aristocracy, too, who periodically stowed it away from view.

In 1985, then, when a Lithuanian man named Bronius Maigis razor-slashed, then acid-splashed the canvas center, rookie psychoanalysts might have called out vicarious sexual violence. Yet Maigis himself declared it an act of political protest: He’d chosen the very day that, in 1940, Lithuania lost its independence to the USSR. All the more reason, perhaps, that the uncompromising Kremlin vetoed pessimistic museum experts to demand restoration straightaway (while censoring Maigis’s motives and shipping him to an asylum). Aided by an obscure 19th-century copy and a balm of honey and sturgeon glue, conservators would take the next 12 years to reconstruct the original’s sly and glorious provocation.

THE THIEF: PABLO PICASSO’S “LE PIGEON AUX PETIT POIS”

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487268457971-8IMRHI19OTAOFSBDC66R/3.-Picasso-Le-pigeon-aux-pois1.jpg)

_Cunts. I slipped into the Musée d’Art Moderne after lights out like I’d been invited. Because I fucking could, that’s why. It was genius. Place had a faulty alarm system and three sleeping guards. I planned for months. Swiped a Picasso, a Matisse and a few more—about €100 million worth. I’m a criminal satisfying a criminal thrill. I’m menacing, skulking, the coyote who haunts your farm. I’d just as soon massage my knife into your throat to get my pulse going. Because conscience is just a bullshit weakness that hums under the skin. It swims in your blood like red tide, crowding the coward’s heart. You think you know me—some skinny kid growing up in the projects, the cmpaћapa, putting myself to bed hungry as cries echo from my belly like frogs in the dark. Yeah, you think you know. I’m just like you, but I’ve got balls. When God calls time-out and we all quit playing, when the bombs drop and the stores are looted clean and every last generator chugs to an asthmatic halt, I’ll torch these so-called masterpieces just to keep my fucking tootsies warm._

Pablo Picasso takes the prize for most pilfered artist in recorded history: to date, nearly 1,200 of his works have been reported missing by the Art Loss Register, and that’s not counting those believed to have perished in a 1943 Nazi bonfire of “degenerate art.” “Le Pigeon aux Petit Pois,” painted in 1911, was a seminal work of the cubist avant-garde movement. The work was taken by a single, stealthy thief in the spring of 2010 from the Musée d’Art Moderne. In terms of value, it’s one of the biggest heists of our time, as the thief also managed to swipe Henri Matisse’s “La Pastorale,” Amedeo Modigliani’s “La Femme à l’éventail,” Georges Braque’s “ L’Olivier Près de l’Estaque,” and Fernand Léger’s “Nature Morte aux Chandeliers.” Combined, the estimated value is $123 million, and the identity of the thief remains unknown.