[](#)[](#)

A lamp to bring poon from the darkness

An exploration of tastefulness with Douglas Tirola, filmmaker behind Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead: The Story of National Lampoon

Rewind to May of this year, when the “Twittersphere” caught fire following a stand-up routine that comedian Louis C.K. delivered on _Saturday Night Live_, where he incisively satirised racism and child molestation.

“Wow—that Louis CK monologue was not only terrible, it was actually offensive,” one user tweeted.

“SNL shouldn’t have aired it”, opined another.

“Bad taste”, commented one.

Fast forward to today at the Andaz hotel in Los Angeles, where I meet filmmaker Douglas Tirola to discuss his hilarious new documentary _Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead: The Story of the National Lampoon_.

The topic of Louis C.K.’s controversial monologue comes up. “It made news, asking if he went too far,” Tirola says, “but the news wasn’t about _what_ he said, the news was that he said something that went too far.”

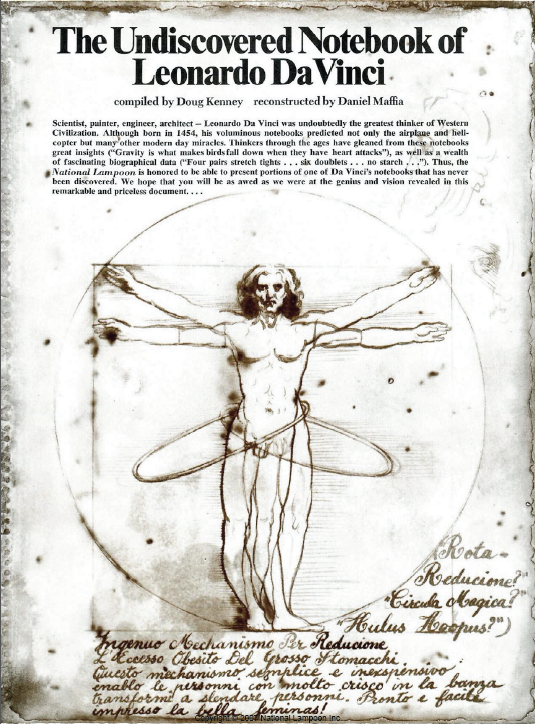

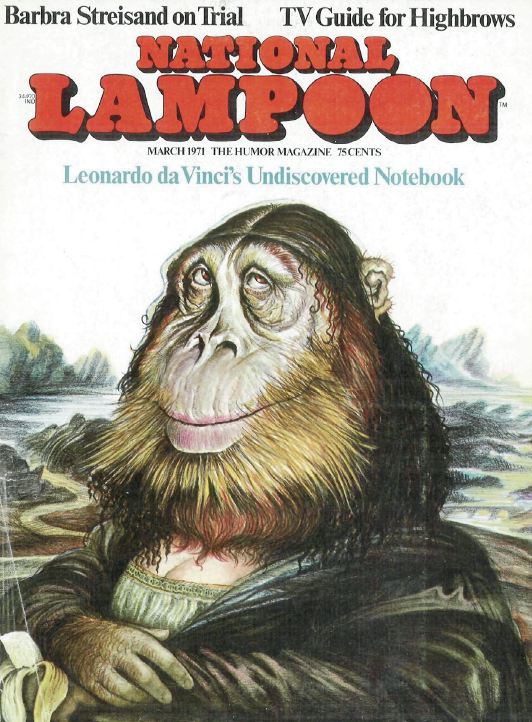

Rewind way back now, to Boston 1969, where two Harvard grads license the rights to create a spin-off of “The Harvard Lampoon”—the campus humor rag that has been running since 1876. Their names are Doug Kenney and Henry Beard. The magazine becomes “National Lampoon.”

It’s now 1971. The new issue of National Lampoon hits newsstands with a cover illustration of court-martialled Vietnam War mass-murderer William Calley—who killed 22 unarmed South Vietnamese civilians in the rural township of My Lai. Calley is drawn sporting the do-eyed grin of Mad Magazine’s fictitious mascot, Alfred E. Neuman, complete with the catchphrase “What, My Lai?”

Bad taste or incisive satire?

As co-founder Beard described the experience years later: “There was this big door that said ‘Though shalt not.’ We touched it, and it fell off its hinges.”

“People were focusing on what the story, essay or art _was_, not on the fact that it went too far.” Tirola adds, “it’s not so much that you can’t say these things today, it’s more that there is such potential consequence for saying these things that the collateral damage, whether it’s at a stand up, a dinner party, or on a show is so horrifying, that it’s not just about political correctness—it’s self censorship.”

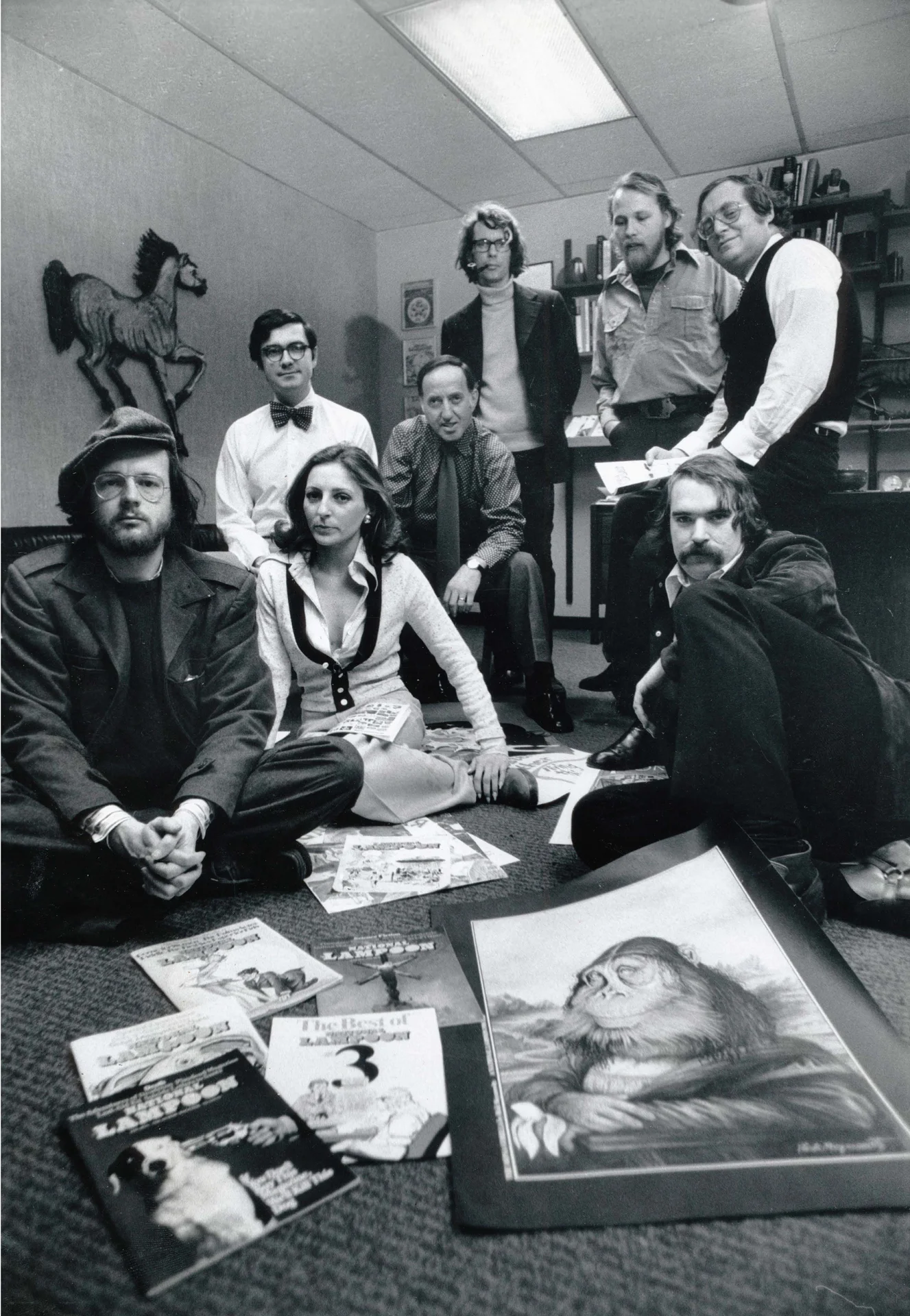

It’s 1974 and National Lampoon has a peak year of one million issues sold, with an estimated outreach of over fifteen million readers, thanks to word-of-mouth and not-safe-for-work articles and cartoons passed under the table. It is one of the most popular humor magazines in America and begins spawning radio shows, live theatre, recordings, books and, by the end of the 70s, feature films such as _National Lampoon’s Animal House_ and _National Lampoon’s Vacation_—introducing the world to actors such as Chevy Chase, John Belushi, Bill Murray, Harold Ramis and iconic director John Hughes, many of whom went on to become part of Saturday Night Live’s original wave of actors and the creative forces behind era-defining movies such as _Caddyshack_, _Ghostbusters_, _The Breakfast Club_ and _Ferris Bueller’s Day Off_. Or to put it simply, as Hollywood heavyweight filmmaker Judd Apatow says in _Drunk Stoned_, “National Lampoon became _all_ of modern comedy.”

“We had a screening at Tribeca”, Tirola recalls. “They do a very nice thing for their sponsors where they pick a couple films to have a private screening for their people. This nice bank picked our movie and I thought, ‘this must be the coolest bank ever!’ I’m standing at the back and there’s nobody laughing…except for three people in the front. So after the screening I ask who those three guys were. ‘They’re our clients’, I’m told”. Tirola leans back, smiling knowingly. “No one’s going to criticize the clients – they’re just enjoying the movie, no holds barred. But the people from the bank who are sitting next to their peers were nervous, because they were worried they would be judged. For laughing.”

When I try and suggest that modern society has grown increasingly bereft of a comedic edge, Tirola reminds me that there’s more to it than that. The 1970s saw the burgeoning boomer culture, the immediate aftermath of the Civil Rights movement, and the Vietnam War. There was friction, energy and political and social upheaval. But the times didn’t physically create the Lampoon, Tirola reminds. People did, including the larger-than-life Kenney, the intellectually revered Beard, the visionary art directors Michael Gross and Peter Kleinman, and the writers Chriss Miller, P.J. O’Rourke, and Michael Donoghue.

Fast forward to today where _South Park_ carries the bad taste torch that the Lampoon ignited forty-five years ago, but few, if any other programs attempt comedy as cutting. It seems as though we’ve exited the era when a smart, tasteless joke could make you laugh out loud without worrying about hurting someone’s feelings or being attacked on social media. What happened?

“I think as we share less common experiences, there’s less to grab on to,” Tirola muses. “What is right, what is wrong, how do we relate to one another. The easiest thing to do is to show people you care, not by making an effort but by criticizing something else, which is just like jealousy and envy. You don’t go down to Arkansas or Mississippi to be part of any civil rights march, you just point out that the person at the other table at your country club in Fairfield County, Connecticut is making a bad joke. No effort to do anything or volunteer to go anywhere. Instead, you just point out that somebody else is a schmuck.”

When I relate this back to Louis C.K.’s monologue, Tirola defends the comedian: “The difference between somebody who is just a civilian who is causing all this fear with their criticism and a writer at the Lampoon, or an artist or even a stand up—even a stand up has worked on that joke for hours, if not days, has made their friends sit through it, gone to some comedy club that nobody has heard of to practise it, if they worked at the Lampoon, five other editors or writers have gone over it, criticised it, worked to get it to where it is. It may just be commentary, but they’re working hard at that commentary. It’s not just a line in between a sip of gin and tonic where they’re espousing something. So hopefully the movie serves as a political statement in that way.” Tirola pauses and smiles as though relishing a taste, shaking off the momentary seriousness. “But hopefully it’s at least a little entertaining.”