Donald MacJanet. “MacJanet Campers Swimming in Lake Annecy,” (ca. 1962). Color Slide 2 x 2 inches. Courtesy Tufts University, Digital Collections abd Archive, Medford, MA.

Still from _Summer with Monika_, (1953). 97 minutes. 35mm. Courtesy Criterion Collection.

William Rough. “MacJannet campers ready for chalet inspection,” (1959). Color photograph. Dimensions vary. Courtesy Tufts University, Digital Collections and Archives, Medford, MA.

“Archery at the MacJannet camp,” (ca. 1930). Black and white negative. 2.5 x 2.5 inches. Courtesy Tufts University, Digital Collections and Archives, Medford, MA.

Greg Stimac. “Blue Mountains,” (2007). Archival Inkjet Print. 40 x 50 inches. Courtesy the artist.

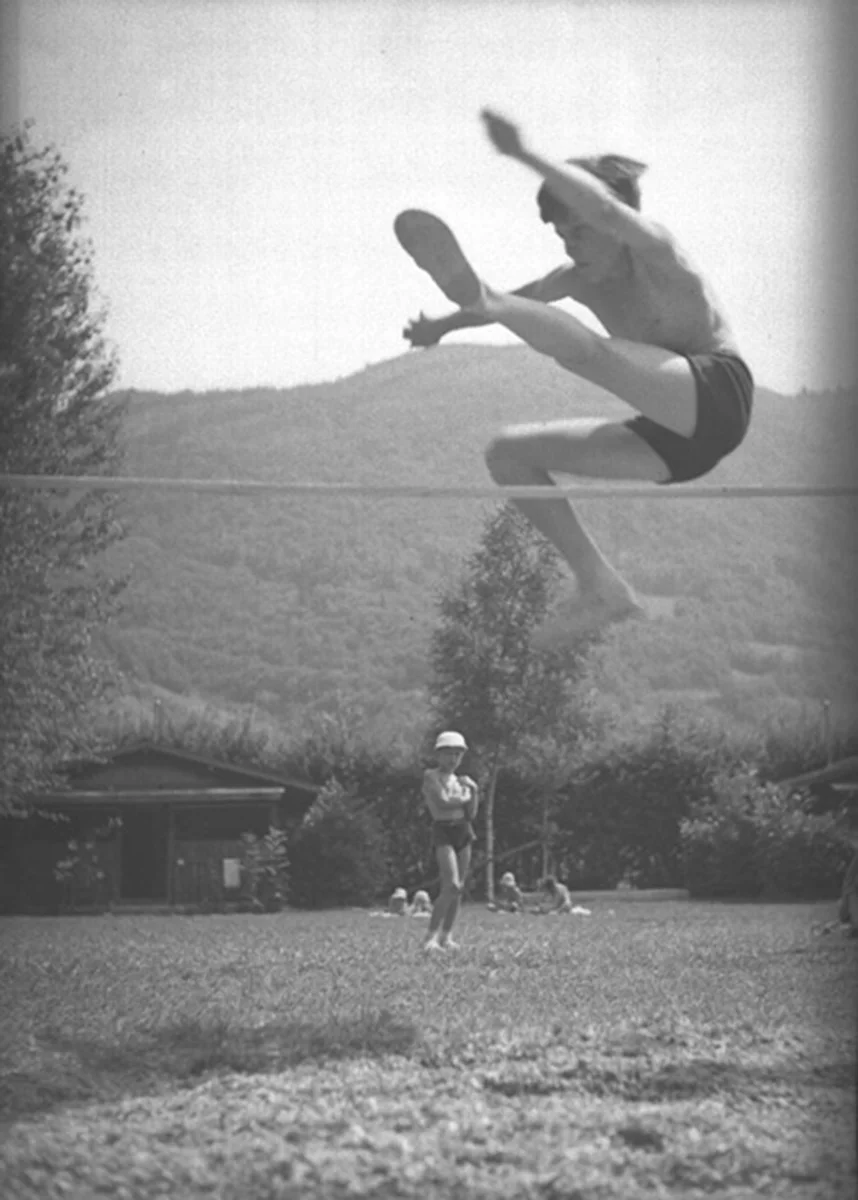

“High jump,” (ca. 1930). Black and white negative. 2.5 x 2.5 inches. Courtesy Tufts University, Digital Collections and Archives, Medford, MA.

[](#)[](#)

I Don’t Know What You Did Last Summer

Assessing What's Been Lost, and What Shan't Return When We Hang up Our Springtime Anoraks

I know people who went to summer camps nestled in the cliffs of Malibu, drenched in pure, uncut California sunshine. Their co-campers were the sons and daughters of actors, directors, studio execs. And I’ve heard of the camps in upstate New York: They sound like _Dirty Dancing_ meets _Blade Runner_, with air-conditioned cabins and every type of precocious accommodation for neurotic silver-spooners from the Upper East Side to the Main Line, and all the helicoptering trophy stepmoms and financier fathers in-between. There are chalets that were erected in the tender period between the World Wars on the shores of Lake Annecy, France, built to introduce well-heeled young Americans to the _just so_ nature of summering in Europe, and a taste of wholesome American camp life for the youth of France, photos of which are featured herein. Far be it from me to tell you what’s a real summer camp and what’s not, but those don’t sound like real summer camps. Here’s what does: The kind of place that makes you viscerally miss the modern conveniences of everything outside of it, but mourn their presence after the momentum of coming home fades.

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487292062253-6HRM5QX07SDX5PQMBJMD/blue_mountains.jpg)

Ours wasn’t a shithole, but we’d been going there for four or five—sometimes even eight—years as campers by the time we got a new dining hall, with air-conditioning. It represented our industrialization, and the first time we stepped in it, we knew our era was coming to an end. It sounds quaint, but so many of us were distilled to our core by that simplicity of living. Sometimes, finding your utopia is simply a matter of learning how little you need once you get there. Anything more is a corruption.

Before I went to the camp that’d go on to be the defining summer camping experience of my life, there were others. A week here or there in the mountains outside town (forgettable), a week at Space Camp (good, not great), day camps as a little kid (the absolute worst, really—surely nobody has truly great memories of day camps), and a western-riding camp in Mayer, Arizona (The Orme Ranch Summer Camp) that my older brother loved, but that I absolutely despised. The horses were dumb. The kids were dumber.

That summer in the entrance to the Grand Rodeo—the big capstone event—in front of all the visiting parents and the rest of the camp, I took a dive off of what—in my memory, is a purebred Clydesdale—after my horse decided he needed to go for a run. I wasn’t embarrassed. As the horses stood lined up next to one another in the center of the rodeo ring and I was waylaid to the side while the national anthem played over the PA and everyone looked on in horror, I got up, dusted myself off, and made my way out of the rodeo arena. In my soon-to-be sixth grade mind, I looked like a badass, like Luke Perry in _8 Seconds_, and got to scream “fuck these fucking horses” during the National Anthem. It felt great. And the Celtic horse gods—or whatever shining deity took mercy on me—left me only with a sprained ankle, so I got to go home early, to the sweet, sweet embrace of central AC and PlayStation 1, all the while swearing off those ignoble beasts, the assholes who rode them, and the rest of that place forever.

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487292012366-WPMXKP1PYKJ1DM8EJRRB/64.jpg)

I wasn’t a fan of summer camp.

You could imagine my surprise and out-and-out disdain when I learned that the next summer, at the close of sixth grade, I’d be shipped off to camp with my cousins who lived in Atlanta. To Jewish summer camp. In the middle of the woods. In Cleveland, Georgia. Even though I was only 13 at the time, being from Las Vegas, I knew enough to be terrified of any places where they didn’t sell liquor, let alone one called White County.

I won’t bore you with the details of how I or anyone fell in love with the place—like any great infatuation, and in the immortal words of The Crystals: It hit me, and it felt like a kiss—but I will say that it’s remarkable that I fell for the place as hard and as quickly as I did, given the way I went to bed every night that first summer genuinely terrified a local Grand Wizard and the rest of his fellow Klansmen were going to come, kidnap my Jewish, city-slicker ass, and flay me like a butterflied cutlet.

I wasn’t the only city slicker as it turned out. And make no mistake: Despite some noble attempts at indoctrination, the place was light on religion, or lighter than it thought it was. Whenever we met kids from the surrounding camps, it was always reassuring to learn that we were the least religious—and thus, the out and out edgiest—of our contemporaries. A good example: the first time I met three of the girls who’d become some of my best friends for the rest of my life—to this day—they were teaching each other how to pop it to _Booty Mix 2_ and asking me who the fuck I was. And oh, yeah: You’ve never met Jewish kids until you’ve met the ones from Miami. I was in awe.

No matter how great or awful you accounted one summer at Camp Coleman over another to be, the fact is, you returned home different every year, and your friends at home could see it; plainly, nakedly. You didn’t even need to say it. When you were younger, you might suddenly be far better at a sport—you developed an absurdly great jump-shot, could pop a kickflip, could serve an ace, could do a gainer off a diving board. As you got older, you’d learn hysterical new variations on the word “fuck.” Your musical tastes would open up—you’d come back listening to music your friends had no idea about (for me: a mash-up of _So So Def Bass All Stars Vol. 2_, Biggie’s _Life After Death_, and yes, Phish). Your voice got deeper. You started coming back tan.

We weren’t that way, until we were, weaned off what were once veins pumping with the sweet, sickly blood-red hue of bug juice onto sex, sweat, and saliva, then we all started showing up full of piss and vinegar too.

The changes changed. They weren’t so obvious but manifested in deeper ways—a turbocharged hormonal edge over your friends back home that made them wonder if you’d just returned from either a free love commune, or Navy SEAL training on the proper way to be an American Teenager. You were suddenly funnier, wittier, smarter, sexualized, unapologetically glowing with hormones, and had been seasoned towards social interactions your friends who stayed home may have felt themselves unready for (like the first year of high school, or later on, leaving to go to college). And if you were like me—if none of your friends from camp lived anywhere around you—you had nobody to talk to about it. That was the best. It was a secret you kept not by choice, but by circumstance, a torrid love affair with knowing what it was really like to be young, alive, and radiating with heat.

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487291990354-48DQ7JRLX81CRQOQ13OU/43.jpg)

That isn’t to say the upshot was perfect.

I’ve only just started to feel possibility in summers again, but it’s just coping, more than anything else. This is going to be the tenth summer in a row now where I haven’t been back, and I don’t think there’s a hard and fast cure for the malaise that creeps in every June through August. Like anything else, it just needs coat after coat of the primer paint of years going by, until it fades into the recesses of what was once a blinding, bright, glaring surface wound. When you spend the majority of your adolescent childhood through your teenage years being shipped across the country for the better part of anywhere from four to nine weeks—and that was me, a full-summer camper—you can never really recover from feeling like you’re supposed to be somewhere else when it gets hot. To that end, for someone who went to summer camp, there may be no more detestable bullshit verbiage than “summering,” the word of choice used by those who escape to the same beach town as everyone else where they’re from, just for the weekend. That’s not an escape. That’s not a summer vacation. That’s a supervised release. You see the return trip as soon as you show up because everyone you ostensibly left behind is right there. While it’s certainly not the case for everyone, the Hamptons, to me, are a special kind of hell.

Summer camps are a terrifying thing to overthink. At the end of the day, they’re just an abstract social construct set somewhere idyllic. You put a bunch of young people in the woods, and give them a social system. Some are employed, but the inventory those employees are dealing with are impressionable young people, at all hours of the day. Your counselors don’t know shit. The odds are that you idolized them and that was one of the first things that shattered in your adulthood—rarely did they live up to your initially religious assessment of them, as gods among lesser humans. Your counselors, for the most part, are best kept as memories. There are exceptions. They are rare. And the moment you became one, you realized just how absurdly delicate—or downright non-existent—the fabric of this construct was. It was handled by a bunch of college kids. This might actually be the miracle of summer camp, that it works, given the mass of those running it. Still, there are rules.

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487292013361-JRFY41SIX3VF3T4CP761/71.jpg)

The rules were the best part.

We flaunted the rules. We were goddamn scofflaws.

The rules are why you’re never going to be in a more sexually charged, peak-hormone-crazed environment than a summer camp. No rules are actually made for breaking, but some are more worth breaking than others. Summer camp’s finest greatness may be in the convergence of rules that, when broken, could land you in a world of shit, but when flaunted, could bring your dumb teenage ass something close to immortality.

Midnight swims. Pranks. Cabin hopping. Dodging security guards in the middle of the night, deploying spycraft. Meeting your girlfriend across the lake in her cabin—or, even more thrilling, having her meet you (the girls who had the moxie to go cabin-hopping were as close to real-life “femme fatales” as we are ever likely to personally know).

Like I said: These are the kinds of rules that weren’t designed to be broken—they’re designed to keep everyone’s shit together, they’re designed to keep the little utopia from collapsing in on itself. Which is why to break them (and get away with it) was, and still is to this day, such an unparalleled thrill.

Most of us got away with it. A few times, we got busted. There were certain lines you couldn’t cross, certain things that would get you ejected. For the record, ten years ago, I got fired before I even showed up. But who could have ever expected them to make an example out of my best friend and I for sleeping through the morning portions of an optional, pre-summer leadership training program? Our friends couldn’t believe it, and neither could we. We didn’t smoke weed. We weren’t busted in a cabin across the lake. Our offense was a joke, especially given there were others who got away with it. And yet, I still won’t snitch to this day. But I’ll say this: We were made an example of. We were devastated.

[](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c346b607eaa09d9189a870/1487292053649-RIP1U3ERTJGXQRKCGO6E/SummerwithMonika_image01.jpg)

We recovered. We’re here. We’re fine.

Every camp has ghost stories, but every camp is actually only haunted by the specter of those who got booted. Short of someone at your camp dying, there was nothing darker to go through than watching a friend get kicked out. My theory is that most of us who got kicked out just loved it more than everyone else. When you shine in its radiance, how could you help but fly that close to the sun? The legal merit of all of our ejections was debatable. I’m still pissed about mine. But it was also the best thing that ever happened to me. Really, it’s amazing that some of us lasted as long as we did.

On the other hand? I now feel bad for anyone who lasted longer. The fuse was gonna burn out or blow up, and in the case of that place, even though it could get ugly, even though being expelled forever damaged those of us unfortunate enough to have been ejected, it really was better to go out with a bang than a whimper. The blast was strong enough to make you never want to go back. It was worse for the people who were jettisoned at the summer’s close and who came groveling back the following year: That’s never not gonna be a problem for them.

Thus: The abomination of the adult summer camping experience. Especially when it’s framed as a restorative act. Once you see it, you can’t unsee it—for me, there’s nothing more depressing or pathetic among some of my friends than trying to recapture everything that was once great about summer camp. Nostalgia, reunions, playing up your secret in-jokes you once had as kids. There’s an awful, creeping quality to it, where—in the presence of any kind of simulacrum—I only feel the stark absence of the real McCoy.

Some of us might be tempted to recapture some of the old glory, and I get why, but I don’t recommend it. The old glory is dead, and we should leave it the way you leave any dead thing: to rest, peacefully, among the ghosts of the past. And while it’s fine to occasionally stop by and pay tribute to these memories, linger too long, and you’ll quickly realize you’re surrounded by the dead, and not much more, and that’s a terrible, terrible feeling to be alive with. Better to pave over the old roads. The new dining hall came and went, and all we could do was hate it. Eventually, we had our fun there. We hated it, but we made it work.

After all, sentimentality is the absolute worst kind of drug: There’s no high, just the fiendish pursuit of something you’ll never have again.